Learning from the abyss on Capitol Hill. What now?

This piece was updated on January 7.

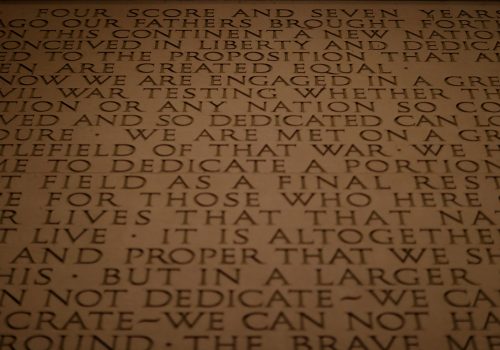

It must be said plainly: Donald Trump, the 45th president of the United States, incited the violence that unfolded yesterday on Capitol Hill through his words and actions since his defeat in the November elections. This fact will remain an indelible stain on America’s more than 230 uninterrupted years of democratic rule.

This made it all the more significant that members of the US Congress, shortly before four o’clock this morning in Washington, DC, executed their constitutional responsibility of certifying the electoral victory of Joe Biden as president and Kamala Harris as vice president. Even Trump at that point, though still disagreeing with the results, recognized that “there will be an orderly transition on January 20.”

Said the Senate Chaplain Barry Black as he stood before weary legislators, closing with prayer one of the most unsettling days of US electoral history, “Thank you for what you have blessed our lawmakers to accomplish, in spite of threats to liberty … and God bless America.”

The series of dramatic events, which will be recounted in rich detail in the coming days and decades, had the United States and the democratic world staring into the abyss of what the national and global ramifications might be of American democracy unraveling. Though disaster appears to have been averted for now, a fuller recovery can only come through studying the lessons of what brought us to this precarious point.

In politics, the reality is that the language and actions of our leaders alter the boundaries of what’s viewed as permissible in public behavior. As the pastor declared in his prayer, “These tragedies have reminded us that words matter, and that the power of life and death is in the tongue.”

Through nearly three decades as a Wall Street Journal reporter and editor, I saw that truth in action in a positive sense during democratic changes in the former Soviet bloc and elsewhere in the world.

More troubling, we’ve witnessed that in a negative way through authoritarian resurgence in places like Russia and China, through the rise of an angry nationalism in weakening democracies around the world, and through a global recession of democratic rights over the past decade, as measured by Freedom House.

Never, however, did I imagine we would see elements of an angry American mob shatter windows and enter the Capitol, the bastion of our democracy, threatening and ultimately disrupting the orderly and usually boringly routine process of certifying the outcome of the 2020 elections.

Worse still was that they were encouraged in their actions by Trump’s tweets and claims, debunked by courts and vote counters across the United States, that Biden was fraudulently elected.

Vice President Mike Pence, witness himself to the horrors inside the Capitol, finally sounded the alarm: “The violence and destruction taking place at the US Capitol Must Stop and it Must Stop Now … Peaceful protest is the right of every American but this attack on our Capitol will not be tolerated and those involved will be prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law.”

It would be Pence who in the early morning hours, breaking with Trump and acting in his role as president of the Senate, declared the Biden-Harris victory and the defeat of his own Trump-Pence ticket.

So, what does all this mean for the Atlantic Council and our work, some sixty years after our birth in 1961?

What does this mean for our founding purpose of promoting constructive US leadership, alongside democratic friends and allies, to protect and promote the common values and interests that prompted our intervention in World War II to liberate Europe and stop the advance of fascism?

How should this influence our sustained international engagement through the Cold War and beyond to safeguard and advance those gains?

What does this mean for a non-partisan institution driven by common cause and not political ideology—by light and not heat?

It means three things:

First, we advance our work with even greater resolve.

Our mission will never be complete, and the dangers that confront our founding purpose will come in different forms at different times. We need to adapt our responses to emerging challenges.

The challenge will sometimes come in the shape of the worst pandemic in a century or a financial crisis. At other times it will come via the tedious but necessary work of constructing and defending the democratic rules, rights, and institutions that define us.

Second, it means that the job of principled international leadership begins at home. The United States has been a desired partner for others in the world because of the power of its democratic ideals, the resilience of its democratic institutions, the strength of its open markets, and its willingness to work in common cause for larger, shared interests.

All of those positive qualities have been challenged. We must play whatever role we can in bolstering them.

Finally, the challenges of our times make action more urgent. We face the combined shock of a global health crisis that is growing worse, an economic downturn that continues, cultural and racial upheavals that are testing our decency, and one of the greatest tests US democracy has ever faced.

None of these tests can be met by a United States as divided as it appeared yesterday or by an incoherent international community without a clearly agreed and defined common purpose.

There is good news and a silver lining in how this saga ended today.

The good news is that more Americans than ever have been deeply engaged in our democracy. As a result of their votes, in two weeks the world will witness the inauguration of Biden as the 46th president of the United States. Democratic institutions and processes will win the day. Biden’s response yesterday was the model of what we expect from our presidents.

“The scenes of chaos at the Capitol do not reflect a true America—do not represent who we are,” Biden asserted.

“The world’s watching,” he said. “Like so many other Americans, I am genuinely shocked and saddened that our nation, so long the beacon of light and hope for democracy, has come to such a dark moment. Through war and strife, America endured much, and we will endure here and we will prevail again, and we will prevail now. The work of the moment and the work of the next four years must be the restoration of democracy, of decency, honor, respect [for] the rule of law … the renewal of politics.”

Yesterday’s shock could be helpful in achieving all of that.

Staring into the abyss motivated the US Congress to avoid it. And perhaps yesterday’s ordeal will jolt our elected leaders in a more lasting manner to realize that they must set aside partisan differences to defend democracy’s hard-fought but still-fragile gains.

The horrid glimpse at the alternative on January 6 should be incentive enough to act swiftly and collaboratively. That’s the message conveyed by the steely return to work of members of Congress as soon as the situation permitted.

If the United States isn’t present as a reliable and principled partner, world leaders will seek other solutions with potentially far worse outcomes for Americans and others.

It’s not enough to simply condemn yesterday’s dangerous, destructive, and illegal violence and the irresponsibility that triggered it. The trauma should prompt us to redouble our efforts within the United States and among allies and partners to simultaneously strengthen our principles and our bonds.

My German immigrant parents, who sacrificed much to embrace the ideals America represented to them and for their family, would have been alarmed at the violence on display at the Capitol. Yet they would have had faith that the country of their dreams would learn from it and improve.

Yesterday’s criminal act by radicals to overthrow American democracy failed, but it will be actions now that will determine whether the problems of the past hours will be another catalyst for the relentless American spirit and make us stronger as a country—and thus as a global community as well.

There is no better time than now to come together in common cause. This is how every member of the Atlantic Council’s global community can play a part, applying the lessons of our collective glimpse into the abyss.

Frederick Kempe is president and chief executive officer of the Atlantic Council. You can follow him on Twitter @FredKempe.

Further reading:

Image: Hannah Gaber-USA TODAY