Chinese President Xi Jinping’s state visit to Washington on September 25 will take place in a much tenser atmosphere than that which prevailed a little under a year ago when US President Barack Obama visited China.

Chinese President Xi Jinping’s state visit to Washington on September 25 will take place in a much tenser atmosphere than that which prevailed a little under a year ago when US President Barack Obama visited China.

Indeed, the US-China relationship has become much more volatile over the past year. Recent cyber espionage scandals, the devaluation of the Chinese currency in August after a bursting of the bubble in the stock markets, and ongoing geopolitical tensions in the South China Sea have add layers of complexity to a relationship already often defined by competing strategic interests. The Obama-Xi summit comes at an inflection point in relations between the two countries.

“President Obama has stayed within the consensus of eight Presidents, going back to Nixon, but that consensus is unraveling,” as the policy community realizes that the assumptions it had about China no longer apply, said Robert A. Manning, a Senior Fellow in the Atlantic Council’s Brent Scowcroft Center on International Security.

The US-China relationship relies on a subtle balance between cooperation and competition, in which “mutual vulnerability”—especially on the economic level—is critical. Manning suggests that “both sides need to find a way to work with each other” and Xi’s state visit needs to produce concrete steps regarding cyber attacks and cyber theft, bilateral investment treaty negotiations, and tensions in the South China Sea.

On cyber security, rhetoric has been escalating for months between the two countries in the midst of high-profile revelations of cyber espionage and cyber theft so out of control that the Obama administration is even considering sanctions against Chinese firms pilfering US intellectual property rights. And it appears only modest progress was made after recent high-level meetings between the two sides to address the issue. These meetings came two years too late for Manning, and, even if sanctions on China were put on hold, “President Obama needs to get some demonstrable progress on cyber issues to have a successful summit.”

“The reported agreement not to attack each other’s critical infrastructure in peacetime is a small step forward, but it leaves Office of Personal Management-scale cyber espionage and cyber theft unaddressed,” Manning said. He was referring to the cyber attack on OPM, revealed earlier this summer, in which hackers accessed the records of more than twenty million current and former federal employees.

Economic relations between the United States and China are also at an inflection point as US businesses—which have been “the foundation stone of the bilateral relationship,” according to Manning—find ventures in China more and more difficult.

Xi’s state visit will perhaps bring momentum to the ongoing US-China bilateral investment treaty, designed to boost foreign investment between the two countries. But negotiations are stalled. The disconnect between the real value of the renminbi—the Chinese currency—and the value set by the Chinese government has also been a contentious issue, and the August devaluation by the central authorities was dubbed by some US presidential hopefuls as a threat to the US economy.

More than the currency issue, the real test for Manning is whether China fully liberalizes its financial markets and allows the market to have a “decisive role” in determining value as China has said is the goal of its market reforms.

International security is at the core of much discord between China and the United States as the two sides, more often than not, have opposing strategic interests at play. Tensions in the South China Sea have also been at the center of attention for several years, and remain an issue the United States is monitoring as China expands its reach in the region by building artificial reefs and ramping up its military presence.

The United States has also been asserting its presence in the region by providing military support to some of China’s neighbors, such as Vietnam and the Philippines. As a core area for the Chinese territorial sovereignty claims, tensions will continue to simmer around this issue and there is “only so much the United States can do,” said Manning.

Room for cooperation

There are opportunities for cooperation in some regions where China and the United States have shared interests and objectives. Manning underscored that both countries are supporters of the Iran deal, and that the Chinese promotion of stabilization in Afghanistan and support for the Iraqi government against the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) are in line with US objectives. This is why “a serious initiative that would demonstrate partnership and cooperation could be the Middle East,” said Manning.

If, ultimately, Obama needs to show concrete results to the American public after the state visit, Xi is going after a different objective: “[he] wants to send a message back home that he is treated as the head of state of a respected, major global power,” said Manning. Concrete plans for further cooperation are therefore not the number one token Xi is after. And, as Manning notes, the challenge that remains is “to make sure that the relationship is more cooperative than it is competitive, because if the balance tilts the other way we are in trouble.”

Romain Warnault is a Publications Coordinator at the Atlantic Council and the former Editorial Manager at the French Center for Research on Contemporary China.

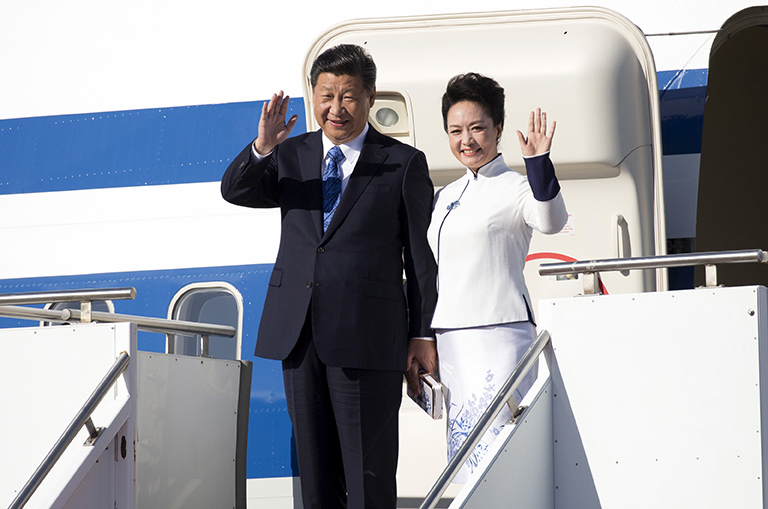

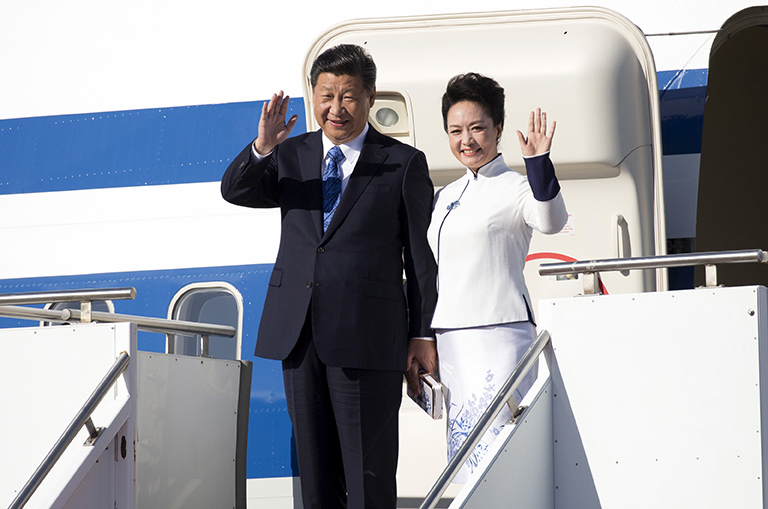

Image: Chinese President Xi Jinping and First Lady Peng Liyuan arrive at Paine Field in Everett, Washington, September 22. Xi will meet US tech titans and tour Boeing Co's biggest factory and Microsoft Corp's sprawling campus near Seattle this week as he kicks off a US visit that also includes a black-tie state dinner at the White House hosted by President Barack Obama. (Reuters/David Ryder)