The White House rationale for assassinating Qasem Soleimani early January 3 in Baghdad strains credibility. If the commander of Iran’s Quds force was planning an impending operation that might cost American lives, the rather frail sixty-two-year-old commander wasn’t going to strap on night-vision goggles and pick up an assault rifle out the attack himself; he did so in coordination with young field commanders and with the approval of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council, which can continue to pursue the plan.

The US State Department’s Iran policy adviser Brian Hook claimed Soleimani was planning attacks on private-sector and official US interests in Lebanon and Iraq but provided no further details or evidence.

More likely than not, the United States may have picked up some chatter of an impending action here or there, which a White House that mostly disregards intelligence professionals twisted to justify a killing they sought for its own purposes.

US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo claimed the attack was “defensive.” What we know for certain is that the killing hardly made Americans safer. If an Iranian-sponsored attack on Americans was possible before Soleimani’s killing, it is a near-certainty now. US officials in Baghdad urged Americans to flee the country, and quickly, warning them to stay away from the US embassy.

The Pentagon immediately dispatched 3,000 additional US troops to the region, less than three months after US President Donald J. Trump tweeted, “The Endless Wars Must End.”

It would be crude to say that Donald Trump ordered the assassination to distract from his domestic political troubles that include an impending Senate impeachment trial. In any case, it won’t work. The decorum that long prevented US leaders from fighting each other over foreign policy matters has long since fallen away, Democrats immediately hammered away at the killing, potentially adding to Trump’s woes.

What we do know that Trump has an emotional and fiery temperament and takes matters personally. Attacking a military base in northern Iraq and killing an American contractor is one thing. But sacking a US mission in the Middle East under his watch—and making him look like Barack Obama or worse, Jimmy Carter—was unacceptable, especially at the start of an election year.

That Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei, went on Twitter to insult Trump a day later—insisting Trump “couldn’t do a damn thing” to Iran while retweeting one of Trump’s threats added insult to injury.

Certainly some Washington pundits obsessed with Iran may believe that through Trump they can realize their regime change dreams, and that killing Soleimani is a step in the downfall of clerical leadership.”

Contrary to the assertions of many Beltway analysts, Soleimani was a fading military figure; he had become more of an inspirational character with a mostly political portfolio involving brokering deals between various squabbling Iraqi Shia political factions. The day-to-day operations of the Quds force have for years been in the hands of younger, hungrier brutes, with fieldwork and training in Iraq, Syria, and Yemen often delegated to highly experienced Arabic-speaking Lebanese commanders.

Just as certainly, the United States’ failing Iran policy has not made Iran militarily weaker or reined in its actions. But it has alienated and frightened US friends in Europe and Asia, who gaped with the same shock at the assassination of Soleimani as the crowd watching King Joffrey order the beheading of Eddard Stark on Game of Thrones.

And almost definitely the killing made the Middle East far more volatile and unsafe for both Americans and Iraqis, Syrians and Iranians, at least for now.

But the truth is that Trump and his supporters don’t really care about remaking Iran or maintaining the security architecture of the Middle East. They have little concern for the United States’ allies in Europe and Asia.

They do care about Trump’s image as a tough, Jack Baueresque action hero who saves the day with his daring, and that may very well be the real motive behind the killing: it was good politics.

Borzou Daragahi is a journalist and a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Middle East Programs.

Further reading

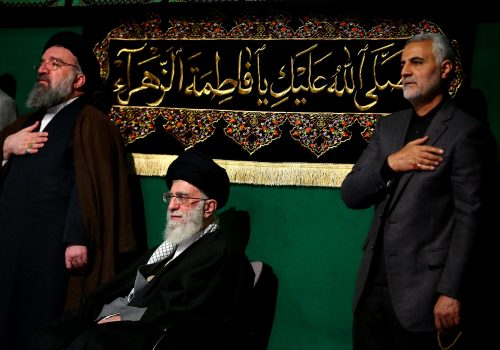

Image: An Iranian demonstrator holds a picture of the late Iranian Major-General Qassem Soleimani, during a protest against the assassination of Soleimani, head of the elite Quds Force, and Iraqi militia commander Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, who were killed in an air strike at Baghdad airport, in front of United Nation office in Tehran, Iran January 3, 2020. Nazanin Tabatabaee/WANA (West Asia News Agency) via REUTERS