After a year of secretive legal proceedings, Saudi Arabia announced on December 23 the sentencing of several individuals in connection to the brutal 2018 murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi. But the exoneration of Saud al-Qahtani, an advisor and lackey of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS) was glaring.

For a purported lack of sufficient evidence, Saud al-Qahtani was not even brought to trial. This tells us one of three things: One, Saudi Arabia no longer values its relationship with the United States; two, the US intelligence community sees greater value in monitoring al-Qahtani’s activities than in seeing him imprisoned; or three, the Saudi court system is, impressively, more evidence-based than we knew.

If the third is true and the first is not, there is one way for the Saudis to prove it, and one assurance the Saudis should give the United States.

Holding Saud al-Qahtani accountable for the operation that murdered Jamal al Khashoggi was a specific, immediate ask of the US government. His continued presence in the crown prince’s inner circle was a red line. To stand by the relationship, the US government needed to see sanity restored to Saudi decision making in the form of al-Qahtani’s removal from top level deliberations and the reassertion of wise counsel from advisors long-trusted by the United States and European partners.

At the National Security Council at the time, we intended to sanction CSMARC, the organization run by al-Qahtani. To their credit, the Saudis proactively shut the organization down and distributed the civil servants working for him to various offices run by others. However, al-Qahtani was not taken into custody, and there were regular reports of purported al-Qahtani sightings in places like Jeddah.

Since then, the assumption has been that al-Qahtani was kept out of public view with the hope that the issue would blow over, while he continued to carry out many of his previous nefarious functions, like hacking alleged dissidents and creating falsehood-based propaganda.

The United States continued to insist that justice would not be served by punishing scapegoats in al-Qahtani’s stead. His exoneration for lack of sufficient evidence is a farce and a slap in the face of the goodwill that the US administration has shown to Saudi leadership in the aftermath of the Khashoggi incident, at no small expense to Washington’s reputation internationally.

Still, there are two conditions under which this exoneration should not be read as a devaluing of the US-Saudi relationship.

One, if the US intelligence community conveyed to Saudi counterparts that collecting on al-Qahtani’s activities is more useful than imprisoning him. The exoneration of Saudi intelligence official al-Asiri makes this condition plausible.

Two, if the Saudi court system is more independent and evidence-based than previously understood. Proof of this can only come from witnessing Saudi courts issue additional and continued unbiased judgements. In the absence of such judgments, this condition is dismissed.

But let us assume this condition is met. There is a risk that al-Qahtani’s exoneration by a defensibly unbiased court will be used to justify his return to favor.

If this happens, it tells us that the Kingdom thumbs its nose at the Saudi-US relationship. Why? Because, separate from the court’s ruling, it is the Saudi leadership’s choice whether or not to maintain a relationship with al-Qahtani.

Out of respect for the bilateral relationship, Saudi Arabia should not restore al-Qahtani to his place as the MBS-whisperer. He should not draw a salary from the government, and he should not be in contact with the crown prince over social media messaging apps. Aside from the obvious foreign relations benefits, why is this in the Kingdom’s interest? Because the logical question after this exoneration must be, if Saud al-Qahtani did not oversee the murder of Jamal Khashoggi, who did?

The core US interest is not al-Qahtani’s removal from society but his removal from the crown prince’s decision making. His place in or out of jail does not matter. His influence on the Kingdom’s policies going forward does.

Kirsten Fontenrose is director of the Scowcroft Middle East Security Initiative at the Atlantic Council. She previously served in the Trump administration as senior director for Gulf Affairs at the National Security Council.

Further reading:

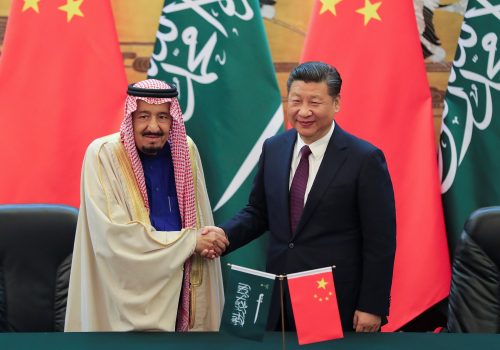

Image: Saudi Arabia's Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman attends the Gulf Cooperation Council's (GCC) 40th Summit in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia December 10, 2019. Bandar Algaloud/Courtesy of Saudi Royal Court/Handout via REUTERS