While US President Donald J. Trump’s actions on infrastructure permitting, including executive orders to expedite approvals of controversial projects like the Keystone XL and Dakota Access pipelines, grabbed headlines, they are potentially counterproductive. Rushing environmental review and infrastructure approval processes could ultimately undermine Trump’s efforts by leaving those projects vulnerable to court challenges as a result of cutting corners, particularly on environmental impact reviews.

While US President Donald J. Trump’s actions on infrastructure permitting, including executive orders to expedite approvals of controversial projects like the Keystone XL and Dakota Access pipelines, grabbed headlines, they are potentially counterproductive. Rushing environmental review and infrastructure approval processes could ultimately undermine Trump’s efforts by leaving those projects vulnerable to court challenges as a result of cutting corners, particularly on environmental impact reviews.

One of the Trump administration’s priorities, welcomed in some quarters as a potential area of bipartisan cooperation, is infrastructure, including improving the efficiency of infrastructure approval and permitting. Meanwhile, efforts to reform the process of preparing environmental reviews for infrastructure permitting under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) are nearly as old as the Act itself.

The Trump administration’s efforts to streamline NEPA reviews, and by extension the process of infrastructure project proposals, thus far follow in the footsteps of efforts by previous administrations, both republican and democratic, which culminated in the 2015 passage of the bi-partisan Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST) Act. The Act created new, cross-agency mechanisms to expedite environmental reviews of important infrastructure projects by facilitating coordination and cooperation.

Not all of the moves made by the White House to streamline the infrastructure approval process have represented progress, and could prove at odds with the environmental integrity of the infrastructure projects in question. For example, at the same time the White House issued specific orders approving the controversial pipelines, it issued Executive Order (EO) 13766, which grants the Council of Environmental Quality (CEQ) chair general authority to identify and manage streamlined permitting for high-priority infrastructure projects.

Rather than streamlining the review process, however, EO 13766 created confusion about how that EO would relate to existing efforts, including the reforms under the FAST Act.

More recent actions by the administration demonstrate that important (but often tedious) work to implement effective reforms is underway. For example, the CEQ issued a little-reported notice on measures it will take to streamline NEPA reviews following up on an August executive order (EO 13807) aimed at expediting infrastructure permitting. Additionally, the US Department of State recently issued important clarifications on its presidential permit process, preventing changes in name, ownership, or control of permits from triggering extensive review if that change does not have environmental impacts.

However, backward steps were also included in EO 13807 which would likely undermine environmental integrity of permitting decisions and potentially put permitting decisions at higher risk of being invalidated in court challenges.

First, EO 13807 rescinded the Federal Flood Risk Management Standard, which provided directions to agencies on minimum standards in building resilience to future flood risk, including increased risk from rising sea levels and climate change. The short-sightedness of removing—and not replacing— federal flood risk management standards was highlighted by the devastation of hurricanes Harvey and Irma and the need to rebuild more resilient infrastructure. Administration officials have indicated that the damage from these hurricanes highlighted the need to rapidly implement new flood standards.

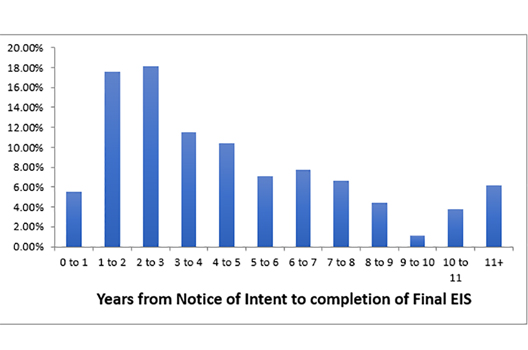

Second, EO 13807 set a target of two years for completing Environmental Impact Statements (EIS’s). The US Department of Interior subsequently announced an even more aggressive policy, which would limit EIS preparation to one year and 150 pages. Complying with these arbitrary limits is likely to result in more successful court challenges to the validity of these statements because these arbitrary deadlines would encourage agencies to inadequately evaluate projects or miss issues. Currently, less than one quarter of EIS’s are completed in two years or less, while approximately 5 percent are completed in one year or less.

Time to Complete EIS’s Issued in 2014

SOURCE: National Association of Environmental Professionals

This risk of cutting corners in NEPA reviews has been highlighted by various court decisions invalidating EIS’s for inadequate information on environmental issues. For example, the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals recently invalidated a Bureau of Land Management (BLM) EIS for a decision to issue coal leases in Wyoming because it failed to consider climate change impacts of downstream emissions from burning coal. In 2016, the long-suffering proposed offshore Cape Wind project was further delayed when a court found the Department of Interior’s EIS did not include sufficient site-specific geological data. While these EIS’s were not rushed, imposition of new, arbitrary deadlines will increase the occurrence of such invalidations by pressuring agencies to finish EIS’s, even if they have not fully developed the necessary information.

However, despite these missteps, the recent CEQ notice and much of EO 13807 made important advances towards streamlining reviews by focusing on the underlying, well-known structural issues that lead to longer review times. Most complex environmental reviews require cooperation among many agencies to prepare the EIS’s and to approve permits. This cooperation is hampered by inadequate mechanisms to facilitate agency coordination. Building on measures from the FAST Act, EO 13807 makes important progress toward strengthening procedures and oversight to improve agency coordination.

One component of better agency coordination is sustained, high-level political attention. Agency decision-makers need to know that it is priority to devote resources to environmental reviews even when they are not the lead agencies, and when disputes arise they need to be able to quickly elevate those issues to an authority (typically White House officials) that can resolve the dispute. Better training is also required to help overcome undue agency cautiousness, particularly where the safest way to reduce litigation risk based on the environmental integrity of infrastructure projects is often thought to be more studies, more time, and more pages.

To address these issues, EO 13807 contains measures to ensure high-level attention to permitting by providing more accountability (in performance reviews and employee compensation) if agencies underperform in environmental reviews. The CEQ initial implementation notice for EO 13807 recognized that real streamlining will require not just better coordination and organization, but a broader update in guidance on all aspects of environmental document preparation.

However, although some of the actions outlined in the EOs could contribute to streamlining permitting processes and environmental reviews, there is no quick solution. Amid hiring freezes and proposed budget cuts, agencies’ abilities to carry out NEPA and permitting reform could be compromised. Ultimately, improvements in coordination and incentives will amount to little if there are not enough staff available to diligently oversee preparation of defensible environmental documents and provide for a sound and thorough review process.

The current administration has taken important steps to streamline infrastructure permitting by beginning to improve bureaucratic processes and training. However, these efforts may fail to make progress by also imposing arbitrary limits on preparation time even as these documents are likely subject to multiple rounds of court-directed review, and by failing to provide adequate resources to agencies.

Keith J. Benes is managing director at Euclid Strategies LLC where he provides strategic advice on energy policy and complex environmental reviews. He previously served as the US Department of State’s lead attorney managing permitting reviews for major infrastructure projects, such as the Keystone XL pipeline.

Image: Construction work continues on Sunoco's Mariner East II natural gas pipeline near Morgantown in Chester County, Pennsylvania, August 1, 2017. (REUTERS/Charles Mostoller)