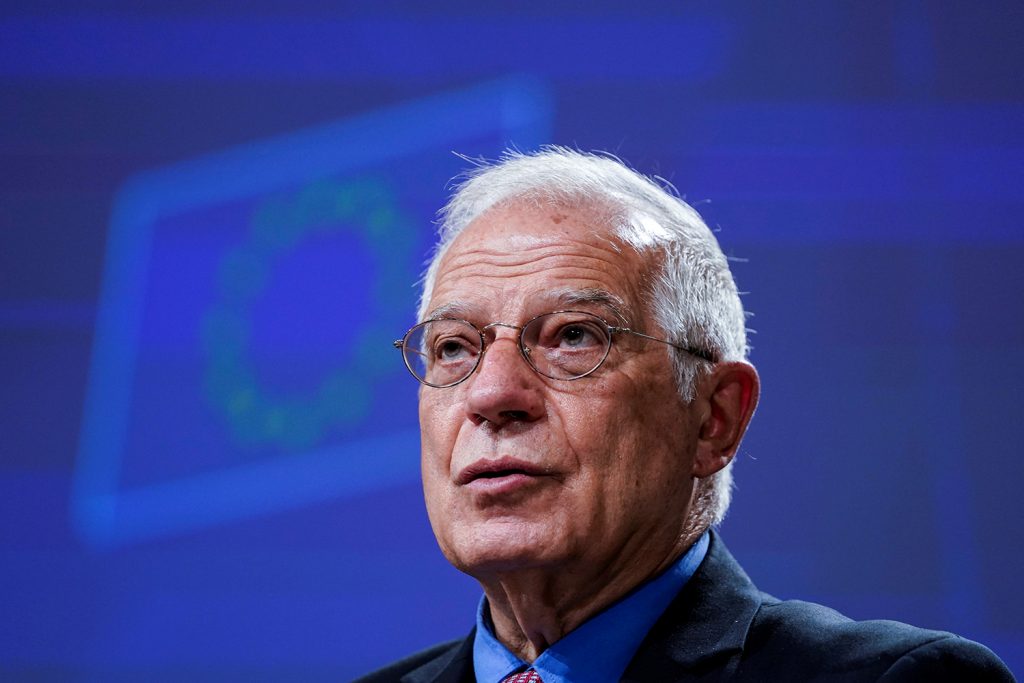

At the virtual EU Foreign Affairs Committee meeting this week, foreign policy chief Josep Borrell invited the United States to a dialogue on China. US officials would be well-advised to take him up on the offer.

Despite Brussels’ strong track record as a regulatory heavyweight, its foreign policy is a work in progress. But while some in Washington may doubt the EU’s ability to take firm foreign policy action, those best placed to execute a cohesive China policy on behalf of the EU are the economic and regulatory experts in Brussels who understand the complexity of the tools necessary to address Beijing’s rise.

Across a wide range of disciplines, the EU’s technocratic institutions repeatedly serve a force-multiplier for US priorities and can help forge the common transatlantic policies necessary to protect US and EU economic and security interests in the face of a more assertive China.

Despite endless handwringing across US administrations over inefficiency and bureaucratic process in Brussels, practitioners know that God is in the details. Whether on data sharing, finance, and—dare I say it—trade, those immersed in the decidedly unsexy fine print of regulatory policy know that it is much easier to hammer out one agreement with Brussels instead of twenty-seven different agreements with the member states. Frustrations abound. There are barriers to entry, protectionists in free-market clothing, and eccentric personalities working at cross-purposes. But as Washington intensifies its focus on China, anyone concerned with Beijing’s efforts to hamstring unity among EU member states—whether by breaking Group of Seven (G7) unity on Belt and Road when Italy signed up, or through recent coronavirus aid diplomacy—should recognize that Brussels is the driving force to stymie these efforts. And the positions of EU officials on China align most closely with the views of some of the tougher member states.

Given the EU’s well-publicized language on Chinese economic practices and its lesser known Connectivity Strategy (which looks at fostering tech innovation with like-minded countries), combined with strengthened guidelines on investment protection and a budding overhaul to tackle illicit finance across the bloc, we are getting some pretty strong signals: the EU is ready to take action on China. When I started at the National Security Council in April 2017, a prominent European visitor asked about transatlantic priorities for the coming year. When we posited China, she responded “China, really?!” We’ve come very far, very fast, and believe it or not…together.

So now a formalized US-EU dialogue may be the opportunity for a grand transatlantic gesture on one of Washington’s chief (and bipartisan) areas of concern. But as a strict foreign policy matter, the EU may still struggle to leverage its resolve. Perennial critics will contend that foreign policy is still best left to the individual member states. And yes, a top-line exchange of concerns in two hours of our executives’ time won’t get the job done. In fact, it could retrench a longstanding criticism that the EU is interested in broad foreign policy gestures with no hope of execution. And in Washington, respectively, we may tweet big words with little follow up.

But EU-US coordination can help unlock the economic tools of foreign policy, the underworld of the technocrats, an area where the EU has the authority to flex its muscles. Geopolitics in miniature. Geopolitics in fine print. And, perhaps, in the end, a strong deliverable for Borrell’s vision for the EU. A comprehensive dialogue between Washington and Brussels on China should feature the experts, not the rhetoric.

In this dialogue, both sides should aim to cooperate on:

- Defending fair principles in capital markets, to include joint ventures and intellectual property

- Reassessing lending posture of multinational financial institutions for research and development

- Implementing rigorous review of incoming investments for strategic interest

- Strengthening licensing and export controls for critical technology

- Establishing terms of use and regulation of virtual currencies

- Closing loopholes for illicit financial actors

It may be hard to wrap our heads around, but these technical issues have become foreign policy. It’s time to harness the regulatory power of the United States and the EU and then leverage them in defense of a foreign policy apparatus under fire.

Julia Friedlander is the C. Boyden Gray senior fellow and deputy director of the Global Business and Economics Program at the Atlantic Council. She has served as senior policy advisor for Europe at the US Treasury and director for European Union, Southern Europe, and Economic Affairs at the National Security Council from 2017 to 2019.

Further reading:

Image: European High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs, Josep Borrell speaks during a video press conference on the 10th EU-China Strategic Dialogue, at the European Commission in Brussels, Belgium on June 9, 2020. Kenzo Tribouillard/Pool via REUTERS