The European Union’s announcement in September 2018 that it would begin to create a special payments channel with Iran in response to the US withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) once again raises the question of the role of the US dollar (USD) in the international economic order. Under the surface of discussions of alternative payment mechanisms is the legitimate question of the negative impacts of US coercive economic statecraft on the USD status as the leading global reserve currency.

Some argue that if Iran shifted to euro-denominated transactions, it could spark a broader shift within energy exporting countries that would eventually weaken the USD as the reserve currency, as well as undermine the impact of future unilateral US sanctions. William Rich of the Council on Foreign Relations and a former Treasury diplomat in the United Arab Emirates, however, argues that the proposed Europe-Iran payment mechanism is “impractical because such a process would be inefficient and costly and could not guarantee European firms protection from US sanctions, reputational damage, or Iranian misuse. It is most effective as public messaging to the Iranians that Europe is trying to resist American pressure.”

In fact, USD’s role as the global reserve currency is most affected by commercial and economic forces, not by politics. The use of sanctions has been a tremendous tool and there are certainly reasons why overuse of sanctions is problematic, but speeding up the decline of the USD as the global reserve currency is not a major concern. Most close observers are not worried about the euro overtaking the USD.

One necessary condition for a currency to be a global reserve currency is the political stability of the currency’s sponsor, which is not present in the EU at this time. Some observers are more concerned about the RMB (China’s yuan) than the euro. Adam Smith, a former senior official at the Treasury Department, emphasized that “though the USD is being challenged at the margins as yuan clearing and other localized trading processes pick up steam, its central role in global finance is currently unrivaled.”

Additionally, Brian O’Toole, a former senior Treasury sanctions official and nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, noted that “while sanctions overuse may drive other countries to set up mechanisms free of US influence, any erosion of the USD global role depends on much larger economic factors, like liquidity and velocity, than any overuse of a US policy tool.”

As the United States considers its options with respect to the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul on October 2, the Saudis in response to US pressure could in the long term move away from USD pricing and embrace another currency, specifically the RMB, as a mechanism for denominating its oil exports. Smith also noted “despite this, the demise of [the USD’s] centrality could happen precipitously—one thing to watch for would be the willingness of major commodity producers to, as a group, price and accept payment in non-USD.”

With China’s status as the world’s largest oil importer since 2016 and the recent launch of yuan-denominated futures in Shanghai, it may seem likely that this is a reasonably plausible long-term outcome. It is still important to note that China does not stand alone in global oil markets. On its own, China may be the largest importer of oil, but China’s share of global oil consumption (13.0 percent) lagged behind the United States (20.2 percent) and even the EU’s (13.5 percent). In addition, China’s commodity futures markets are much less developed than those in the United States, with average bid/ask spreads much higher than those of New York, Chicago, or London, creating much higher transaction costs for market participants.

Most importantly though, a replacement for the RMB would introduce foreign exchange risk to the Saudis, who currently maintain a peg to the USD. While these pegs have their costs, such as in the mid-2000s when Kuwait chose to adjust its peg in response to inflationary pressures caused by the decline in its real exchange rate, these pegs have also brought stability to exchange rates, inflation expectations, and transaction costs. Though the decline in oil prices coupled with rising interest rates have brought into question the benefits of the pegs, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) executive board found in its latest Article IV Report on Saudi Arabia that the peg “continues to serve Saudi Arabia well, given the structure of the Saudi economy.”

With this in mind, it should be noted that the events of the Future Investment Initiative in Riyadh in October herald the future of Saudi economic statecraft. Despite the withdrawal of high-profile Western executives, Halliburton, Baker Hughes, Total, and other energy firms inked deals with Saudi Aramco to the tune of billions. The appearance of Kirill Dimitriev, the CEO of the Russian Direct Investment Fund, should also be noted. He was joined by a number of high-profile Russian executives, including Andrew Kostin (VTB) and Dmitry Konov (SIBUR). Even in the absence of a major move like repricing oil, it is likely that Riyadh will forge closer economic links with Russia and China.

Looking Back at History: When the USD Overtook the Pound

The consensus view is that the USD replaced the British pound as the global reserve currency in the aftermath of World War II. However, new evidence in 2017 from political economist Barry Eichengreen suggests that the displacement of the pound was, in fact, much earlier. Eichengreen contends that evidence from foreign exchange reserves, international bond issuance, and trade credit indicates that the USD achieved rough parity with the sterling internationally as early as the mid-1920s, driven by the creation of the Federal Reserve and relaxation of overseas branching regulations in 1913.

The USD receded in the 1930s due to the Great Depression, but then overtook the pound in the 1950s, becoming the sole global reserve currency in the aftermath of the pound’s devaluation in 1967. Since 1967, the latter half of the 20th century has seen innovations in financial technology that have made it easier for market participants to hedge or exchange different currencies, engendering a reserve currency environment less inclined to be naturally monopolistic.

The fact that the USD has continued its dominance is largely attributable to the lack of a credible alternative and less so to mere inertia. Though much discussion has been focused on the role the RMB might play against the USD, the euro remains its closest competitor today. This should not come as a surprise. The gross domestic product (GDP) of the EU stands at $19.7 trillion , placing it at rough parity to the United States. However, reserve currency status is influenced by a number of factors, many of which are more significant than market size. Though the United States overtook Britain’s GDP as early as 1860, the USD only became an international reserve currency in the 1910s.

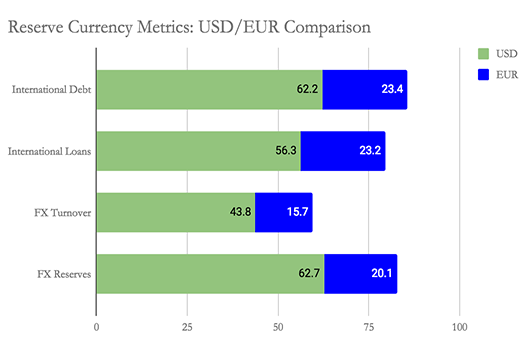

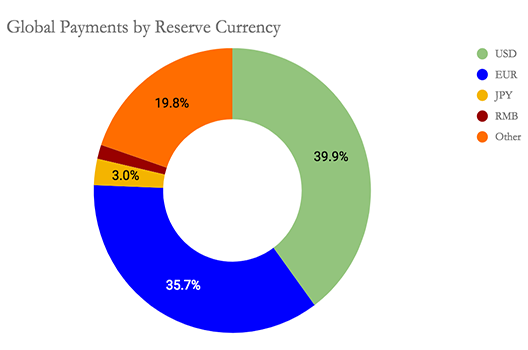

As it currently stands, the European Central Bank’s annual international report states that the euro is in second place behind the USD in most measures of reserve currency status, including foreign exchange (FX) reserves, FX turnover, international loans, and international debt.

Of all categories, the euro is closest to rivaling the USD in global payments—the area most influential for sanctions design. The euro, however, has surrendered significant ground to the USD since 2012, when it accounted for 44.0 percent of global payments, compared to the USD’s 29.7 percent share. In the other reserve currency measures, the euro trails the USD by a significant margin, suggesting that the euro is not a competitive force in the short term.

Though the establishment of the euro initially introduced more liquidity into European markets, this effect has been less pronounced since the onset of the sovereign debt crisis in 2010/11. According to research by the think tank New Financial, European capital markets are only one-third as deep as their US counterparts are, with Brexit potentially worsening the transatlantic gap. The same study found that European capital markets as a whole are half as deep relative to GDP as in Britain.

Existing European initiatives to address this issue, such as the capital markets union and banking union, are critical for the euro to reach a truly competitive stage against the USD. These initiatives, while helpful, are still complicated endeavors. In March 2018, the EU Vice President for the Euro and Social Dialogue, Valdis Dombrovskis, announced a fast-track plan to establish the capital markets union by 2019, but by September, he warned that the target might not be reached. The banking union, which would include the creation of a deposit insurance scheme, remains a hot political issue.

The euro is not currently at a stage where it can contest the USD’s dominance of the international financial system by creating and successfully implementing a special payments channel. The risk of the EU losing access to the $20 trillion US economy and being cut off from the Western financial system for sanctions violations will remain too great of a national security and economic risk. European alternatives to US financial institutions, such as a European Monetary Fund, will encounter significant political obstacles and, in the case of the European Investment Bank, still have USD exposures that can be exploited.

In fact, the German Bundesbank’s recent rule tightening in August suggests that the European special purpose vehicle (SPV) is more a symbolic move than strategic decision. Beyond the EU’s financial institutions, the option of routing some foreign exchange payments through national central banks, such as the Bundesbank, would allow European states to force US sanctions authorities to risk global financial stability in enforcing economic sanctions. The rule change mandates greater compliance assurances with respect to certain suspicious transactions, directly affecting an attempt by the Europäisch-Iranische Handelsbank to withdraw 300 million euros from the German banking system.

These circumstances should not justify an over reliance on sanctions as a policy in every conflict, but can assuage concerns about European efforts to circumvent the ongoing pressure campaign against Iran, as evidenced by the withdrawal of prominent European firms, like Total, Maersk, and Siemens, from the Iranian market.

Former US Ambassador to the European Union and Deputy US Treasury Secretary Stuart Eizenstat highlighted that “the limits of the Euro to avoid US secondary sanctions is a vital national security issue. Although the USD remains the dominant currency in the world, US sanctions must be carefully applied to insure its continued dominance.”

That said, the special purpose vehicle does create incentives and structures to facilitate evasion schemes in the future, thereby providing other jurisdictions with additional diplomatic leverage. Former State Department deputy sanctions coordinator, Richard Nephew, said, “it is not in the US’ interest to create too many of these instances where the rest of the world fights us on sanctions imposition, because they—in aggregate—do what could never be done individually.” Moving forward, he notes, “We have to prioritize what we do and how we use sanctions and flex our USD muscles.”

Although it is highly unlikely that the euro will replace the USD in the near term, since access to the US market is a greater prize than access to most/all other markets, there could be long-term concerns with sanctions. The major concern is whether US overuse of unilateral sanctions will add to political pressures for Europeans to start working in parallel with the Chinese and Russians to challenge the USD and incentivize efforts to support other currencies’ rise such as the Euro and RMB. The possibility of a long-term rival reserve currency or special payments channel should be a policy consideration moving forward as every US administration turns to the sanctions toolkit in National Security Council deliberations.

Michael B. Greenwald is senior advisor to the President and CEO at the Atlantic Council. He was also a former United States Treasury attaché to Qatar and Kuwait.

Image: US dollars and other world currencies lie in a charity receptacle at Pearson international airport in Toronto, Ontario, Canada June 13, 2018. (REUTERS/Chris Helgren)