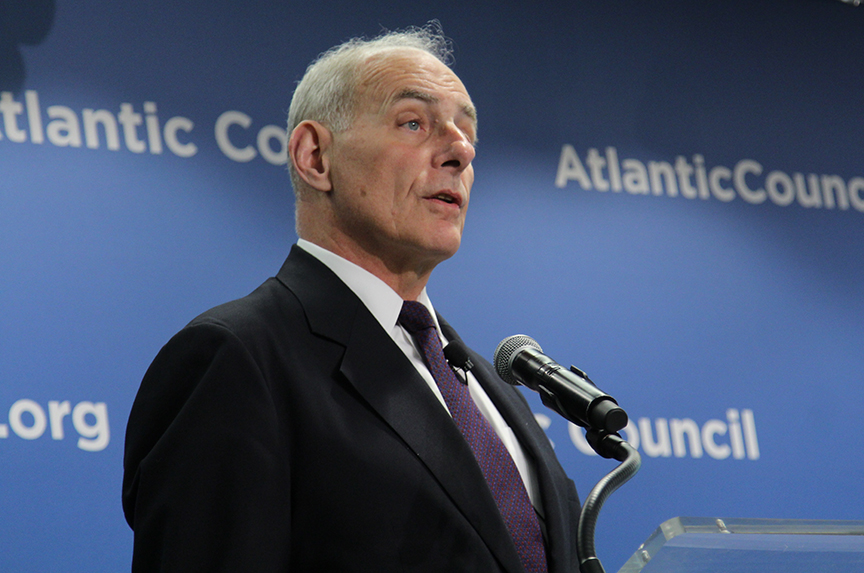

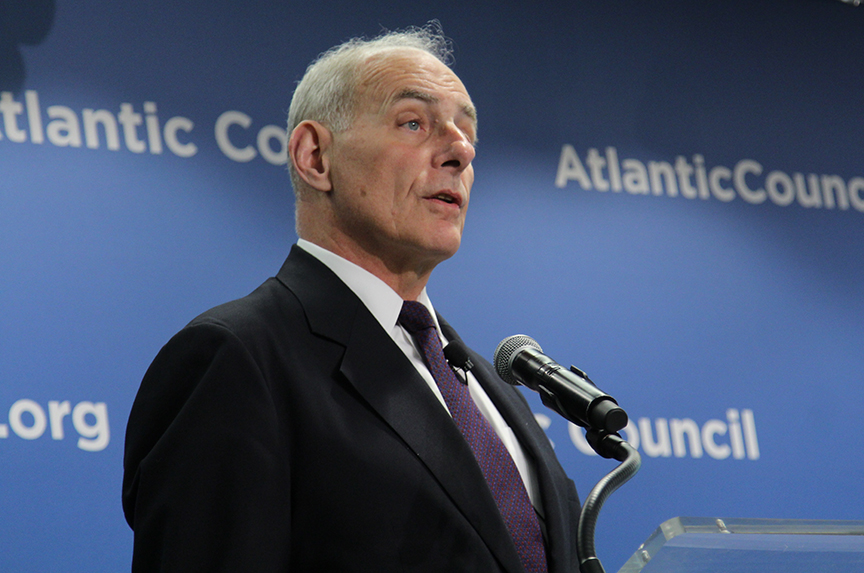

US Secretary of Homeland Security John Kelly says improvement in conditions will reduce unauthorized migration

US Secretary of Homeland Security John Kelly has some advice for people thinking of crossing over illegally into the United States: don’t bother coming.

“The message is, ‘If you get here—if you pay the traffickers you will probably get here—you will be turned around within our laws relatively quickly and returned. It is not worth wasting your money,’” Kelly said at the Atlantic Council on May 4.

People from Central America’s Northern Triangle—Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala—make up the vast majority of migrants crossing into the United States from Mexico.

Kelly credited deportations, US government appeals to civil society in Central America, and an improvement in economic opportunities in those countries, in combination with cooperation between the US and Mexican governments, for the reduction by 70 percent in the flow of unauthorized migrants into the United States. It is worth noting that a Pew Research Center study found that over the past few years more Mexicans are actually leaving than coming to the United States.

The vast majority of Central American migrants who come to the United States do not leave their homes willingly; some are fleeing gang violence fueled by the drug trade and most are seeking better economic opportunities for their families. Human traffickers exploit the migrants by extorting large sums of money.

Once in the United States, the migrants are “victimized,” forced to work in slave-labor-type conditions, and underpaid; some are drawn into lives of crime, Kelly said.

Kelly delivered the keynote address at the launch of a report from the Northern Triangle Security and Economic Opportunity Task Force of the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center. The report offers proposals on how the United States and the three Northern Triangle countries can jointly address long-standing regional challenges. The report is the result of a year-long effort. The recommendations are focused in the areas of rule of law, security, and sustainable economic development.

US President Donald Trump has taken a tough stand on unauthorized immigration. Kelly said the Trump administration is implementing immigration laws “humanely and with dignity.”

“We are not doing anything different than the Obama administration did except we’re enforcing laws across the spectrum,” he said. If members of the US Congress do not like the laws they should change them, he added.

Kelly said he has told Trump that in his view, the job of securing the United States’ southwest border “begins 1,500 miles south.” The United States, the secretary said, has unbelievably good partners in Latin America, such as Colombia, to help stem the illegal flow of people and drugs.

“If we can improve the conditions—the lot of life of Hondurans, Guatemalans, Central Americans—we can do an awful lot to protect the southwest border,” Kelly said.

On the campaign trail, Trump described Mexican migrants as rapists and vowed to build a wall on the southern border to prevent unauthorized immigrants from getting into the United States. Kelly said the migrants coming across the southern border are “good people as a group,” but noted that, due to lack of opportunity, many of the young men get drafted into criminal gangs, such as MS-13, while a lot of women join the sex trade.

Meanwhile, the high demand in the United States for hard drugs—heroin, methamphetamine, and cocaine—has contributed significantly to the flow of drugs. Kelly said the United States has done very little to reduce this demand.

Following Kelly’s remarks, Jason Marczak, director of the Arsht Center’s Latin America Economic Growth Initiative, moderated a panel discussion featuring Laura Chinchilla, a

former president of Costa Rica; John Negroponte, a former US deputy secretary of state; Maria Eugenia Brizuela, a former foreign minister of El Salvador; and Eduardo Stein, a

former vice president of Guatemala. All four are members of the Northern Triangle Security and Economic Opportunity Task Force; Negroponte, Brizuela, and Stein are co-chairs.

Negroponte said that as a result of Central America’s proximity to the United States, the migratory patterns from this region have a direct impact on this country. Chinchilla said Central America is important for more reasons than just its nearness to the United States.

The United States has a “very important moral obligation” toward the Northern Triangle on the issue of drug trafficking, she said. “Most of the problems we have today are explained by the amazing amount of illegal drugs that comes to the United States,” she said, noting the linkages between the drug trade and the high levels of crime in Central America.

Furthermore, she said without adequate US engagement, a deterioration in the security situation in Central America would contribute to a flood of migrants and this will pose serious national security challenges to the United States.

Two years ago, the US Congress deepened cooperation with Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras by approving $750 million in aid through the Alliance for Prosperity Plan. The US Senate on May 4 was voting on an omnibus spending bill that includes $655 million for Central America.

“What we want to do is to help resolve the root causes [of migration] in that part of the world and then integrate it better economically with ourselves and other parts of North America,” said Negroponte.

Countries in the Northern Triangle have had mixed results in their efforts at betterment.

In El Salvador, for example, the tiny nation that was wracked by civil war from 1980-1992 is now ruled by former guerillas from the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front (FMLN). “It just goes to prove how we have consolidated in a peaceful transition of governments,” said Brizuela, while noting that democracy is still weak in her country.

Corruption is a significant challenge facing the region.

Guatemala has had high-profile success in tackling corruption. In September of 2015, Guatemalan President Otto Pérez Molina was forced to resign in the face of corruption allegations. Such an outcome would have been impossible without the support of the Comisión Internacional contra la Impunidad en Guatemala (CICIG), the UN-backed panel that has been helping strengthen judicial institutions in Guatemala.

Stein acknowledged CICIG’s support, noting that as a result of solid corruption cases more than one hundred former public officials are in prison in Guatemala awaiting trial.

On the flip side, Stein pointed to a backlog of three million corruption cases in El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala where the accused have languished in prison for many years without trial. This situation, he said, “is a master’s degree in crime,” while adding that the prison system in these countries desperately requires structural reforms.

Brizuela said there is a need to strengthen institutions and create economic opportunities to address such challenges.

Stein said a key concern voiced in Central America is the same as the one he hears repeatedly in the halls of the US Congress—“that the money is well-oriented and well-spent, and that there are accountability and transparency mechanisms that respond not only to the donors, but to the people of our countries.”

“Part of what we are hoping for… is a better understanding amongst the three governments and the rest of the region,” he added.

Marczak said the Atlantic Council task force’s recommendations are focused on improving prosperity in the region through shared responsibility, but acknowledged positive momentum in the region as a result of local leaders stepping up and investing much of their own money in solutions. For example, 80 percent of the funding for the Alliance for Prosperity comes from the countries in the region.

Addressing the root causes of instability in Central America should be a priority for the United States, said Marczak.

“What happens in San Pedro Sula, Honduras, impacts Americans in Abilene, Texas,” he said. “If we take more concrete, decisive actions now the prospects can be bright; if we don’t, it can get much worse.”

Ashish Kumar Sen is deputy director of communications at the Atlantic Council. You can follow him on Twitter @AshishSen.

Image: “The message is, ‘If you get here—if you pay the traffickers you will probably get here—you will be turned around within our laws relatively quickly and returned. It is not worth wasting your money,’” US Homeland Security Secretary John Kelly said at the Atlantic Council on May 4 in a message directed at Central Americans contemplating coming to the United States illegally. (Atlantic Council/Sean Miner)