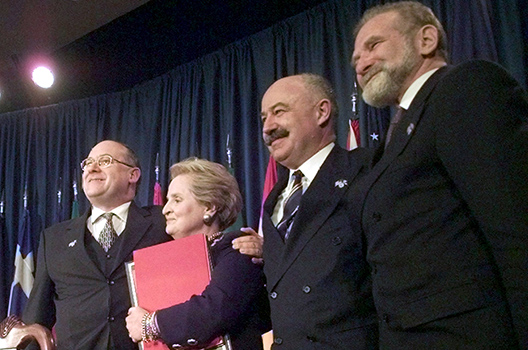

When the foreign ministers of Poland, the Czech Republic, and Hungary finally signed documents completing their nations’ accession to NATO it marked the beginning of a new era for the transatlantic alliance. Twenty years ago, the ceremony held in Independence, Missouri—the hometown of US President Harry S. Truman, who oversaw the creation of NATO—marked the first time former-Communist adversaries had joined the alliance of democracies.

Damon Wilson, executive vice president of the Atlantic Council, was a junior desk officer at the US Department of State when then US Secretary of State Madeleine K. Albright travelled to Missouri to finalize the new enlargement. “For me, less than a year on the job, I was on a professional high,” Wilson recalled. “After watching Washington for years exude ambivalence about whether to welcome more allies into NATO, the compelling case presented by these nations’ extraordinary spokespeople won the day. The determination of Czechs, Hungarians, and Poles, and the subsequent bipartisan leadership of Robert Dole and Bill Clinton, ensured that President George H.W. Bush’s call for a ‘Europe whole and free’ would not remain just rhetoric.”

This was not the first instance of former enemies becoming friends through NATO. The rehabilitation of West Germany and Italy, as well as the reconciliation of former foes Greece and Turkey, have been some of the Alliance’s most significant achievements. But after decades of isolation on the other side of the Iron Curtain, the accession of three former Communist states “marked a historic step in the effort to build a Europe that is undivided, free, and secure,” according to Ian Brzezinski, a resident senior fellow in the Transatlantic Security Initiative of the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security.

Daniel Fried, a distinguished fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Future Europe Initiative and Eurasia Center, explained that when Washington “decided to champion NATO’s enlargement beyond the old line of the Iron Curtain, the United States was investing in a united Europe in the name of common values. That move represented US Grand Strategy at its best: advancing our ideals and interests at the same time.”

Importantly, Fried argued, NATO expansion was better than the alternative at the time, which “would have been a dirty deal with the Kremlin—tacit or otherwise—to consign 100 million Europeans, newly emerged by their own efforts from Soviet domination, to a gray zone of insecurity and probably renewed Russian aggression, as Georgia and Ukraine have experienced.”

The accession of Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic spurred momentum to continue enlargement throughout the next two decades, as seven of their former Communist partners joined in 2004, followed by the accession of Balkan countries Albania and Croatia in 2009, Montenegro in 2017, and the pending membership of North Macedonia. As Christopher Skaluba, director of the Transatlantic Security Initiative at the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security, explained, the first round of enlargement was “a promise to others that membership in NATO was an attainable goal with political and institutional reform.”

While Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic benefitted from the security the Alliance provided them, the new members also brought much to the table. As Brzezinski explained, “these three nations have contributed to US and NATO operations around the world, including distant battlefields such as Iraq and Afghanistan.” All three countries sent troops to Afghanistan as part of NATO’s International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), contributing thousands of troops and personnel. Forty-four Poles, fourteen Czechs, and seven Hungarians lost their lives during ISAF and its successor missions Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Resolute Support. All three still have hundreds of troops in Afghanistan, helping to train Afghan security forces and providing security for military bases there.

Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic also provide key capabilities to other ongoing NATO missions in Europe. Hungary has more than four hundred troops participating in NATO’s Kosovo peacekeeping force (KFOR) and is looking to increase its contribution this year. Poland provides regular contributions to NATO’s Standing Naval Forces in the Mediterranean, Black, and Aegean Seas and for air policing missions in the Baltic. Last summer, the Czech Republic deployed a mortar platoon in Latvia and a mechanized company in Lithuania as part of two NATO Multinational Battlegroups.

Beyond their tangible additions to the Alliance’s missions and operations, the new members also provided NATO a much-needed lift after the end of the Cold War. “At a great inflection point in history, these nations—hyper aware that we were not experiencing the end of history—helped Americans understand the value our alliance and its relevance in the post-Cold War period,” Wilson argued. “Our then-newest allies focused our minds on the need to adapt NATO for the future. It was the process of enlargement, projecting peace and stability by welcoming former adversaries as allies, against the backdrop of the Balkans’ decent into war, that jolted Washington into understanding that a new NATO could be as necessary for our security in the future as it was during the Cold War,” he said.

NATO membership still remains incredibly popular in all three countries, with 79 percent of Poles and 60 percent of Hungarians having a favorable opinion of the Alliance. Poland has met the goal of spending 2 percent of its GDP on defense, while Czech Prime Minister Andrej Babiš has pledged to have his country hit the 2 percent mark by 2024, noting last July that Prague had increased its defense spending by 50 percent since 2013.

According to Fried, the strength the Poles, Hungarians, and Czechs still see in the Alliance should inspire the other member states. “At a time of discontent and self-doubt in the West, it is important to recognize our achievements: thanks to the 1999 and subsequent rounds of NATO enlargement, Europe whole, free, and at peace went from slogan to near reality, to the benefit of the free world, America included,” he said. “That’s worth recalling. And celebrating.”

David A. Wemer is assistant director, editorial, at the Atlantic Council. Follow him on Twitter @DavidAWemer.

Image: U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright stands with Czech Republic Foreign Minister Jan Kavan (L), Hungarian Foreign Minister Janos Martonyi and Polish Foreign Minister Bronislaw Geremek (R) at the NATO expansion ceremony in Independence, Missouri March 12 (via Reuters)