On April 24, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) sent Orders to Show Cause to four Chinese telecommunications companies: China Telecom Americas, China Unicom Americas, Pacific Networks, and ComNet, giving each of them a limited window (originally thirty days but this was extended a few weeks) to provide the FCC with information about their respective companies, technologies, and operations. The orders were issued because the executive branch is concerned that these four telecoms—which operate in the United States but are either owned or effectively controlled by the Chinese government—pose national security risks. It fits with the US government’s growing scrutinization of foreign telecommunications operators within its borders. The FCC has the power to revoke these firms’ Section 214 authorizations that allow them to operate in the United States.

On June 1, two of those companies, Pacific Networks and ComNet, filed a ninety-two-page response to the FCC (Pacific Networks acquired ComNet in 2009). The FCC is now reviewing the response, with the option of a license revocation on the table—which would effectively kick the two companies out of the country. The FCC could also modify the firms’ licenses, require certain mitigation measures (e.g., maybe providing assurances around their technology, or in the way of corporate transparency), or choose to do nothing at all (though that of course is highly unlikely). It’s possible the FCC could wait to decide until it also reads the responses from China Telecom and China Unicom, which have now filed, or it could rule on these two first.

The main claim of the Pacific Networks and ComNet response is that “the Companies are not ‘wholly-owned’ by the Chinese government and operate independently and without ‘exploitation, influence, and control’ of the Chinese government. If the distinguishing factor in the China Mobile Order was the opportunity to have established a foundation of trust with the Commission, and with the US government generally, ComNet and Pacific Networks have had that opportunity and done so.”

The companies also list several reasons why they believe they are different from the China Mobile case, which the executive branch has been holding up as an example of why some Chinese firms should be prohibited from operation in the United States due to security risks. The document speaks of the firms’ “consistent record of complying with the obligations placed on them by their Letter of Assurance to Team Telecom.” (Team Telecom is the informal executive branch entity charged with reviewing foreign telecom security risks and soon-to-be-formalized through a recently signed Executive Order.) The response also cites 2018 requests for information from both the Department of Justice and Department of Homeland Security that found the companies’ cooperation “comprehensive and informative.” It notes that unlike China Mobile, which had “no operating history in the United States,” Pacific Networks and ComNet “have long had facilities and employees in the United States to serve their customers” and “have provided updates as required and provided open and transparent information promptly when asked.” Should the FCC decide to revoke the companies’ licenses, it writes, the revocation would effectively “force them to shutter their operations.”

The response to the FCC argues that even if the FCC can identify security risks after reading the firms’ reply, “the Bureaus must seriously consider the less draconian alternative of entering into an agreement with the Companies to enact protections to mitigate those concerns.” For the Trump administration, which has been looking to forcibly decouple US-China entanglement on several fronts, mitigation measures may not be enough. These measures may also be deficient because of growing concerns within other portions of the US government (i.e., beyond the White House) about Chinese government espionage through telecom networks. But the reply at least makes clear that Pacific Networks and ComNet prefer mitigation measures of some kind over their ultimate worst-case scenario, getting kicked out of the United States.

Several important components of the document explicitly address concerns about the Chinese Communist Party’s influence over the two firms—something the original Orders to Show Cause explicitly requested that each of the four targeted telecoms address. This is especially important as Pacific Networks (ComNet’s parent company) is itself owned by CITIC Telecom International, a Chinese state-owned enterprise. Where the Trump administration has been concerned with any possible or perceived connections to the Chinese government in general, this effective state ownership does in fact raise legitimate security questions.

In response to this set of concerns, there is a declaration from ComNet’s General Manager, Human Resources and Administration, a US citizen resident in California who has served since 2013 as the companies’ US managing officer. “At no time,” they wrote in this declaration, “have any officials of the government of the People’s Republic of China or of the Chinese Communist Party directed or requested that Pacific Networks or ComNet take or refrain from taking any particular action.” The document also contains an organization chart of the firms’ parent companies and investors and of the firm’s board of directors. It also says of the CEO and the CFO that there is “no affiliation” with the Chinese Community Party or Chinese government. While this statement is hardly going to placate those already convinced the CCP exercises malicious influence over the companies, it’s nonetheless in the vein of information the FCC initially requested of the firms.

Potentially more interesting is the redacted information in the PDF on company facilities and the firms’ customers, physical networks, and interconnection agreements (as well as several pages redacted altogether). To date, Team Telecom’s approaches to telecommunications security have relied on both classified and unclassified information about companies, but the Trump administration has pushed to narrow understandings of risk to ultimately come down to company ownership. So, much like the statements swearing no involvement with the CCP, network diagrams may not placate certain hawks. Yet for those in the government and outside of it interested in technical hardware and software criteria to establish telecom supply chain trust, those diagrams may be a valuable insight into potential compromise vectors in these firms’ specific networks.

And finally, the document contains a few records of previous communications with the US government, such as required notices previously submitted to the Department of Justice and the Department of Homeland Security about changes in the firms’ ownership structures. While there has been growing criticism of the inadequacy of US government processes to vet foreign telecom suppliers, this kind of information should illustrate the executive branch’s years-long attention to at least some ways to mitigate risks.

One particular part of the PDF illustrates this point—an email about a June 15, 2015 meeting in Pacific Network’s and ComNet’s Los Angeles offices with representatives of Team Telecom. The ComNet representative’s email about this meeting notes, “During this meeting, Team Telecom was provided a binder of materials and a detailed presentation regarding the structure, network architecture, and operations of Pacific Networks and ComNet.” There is also an email about a meeting on March 22, 2018, between representatives of ComNet and the Justice and Homeland Security Departments in ComNet’s California office that covered similar topics, including, as the email from a DOJ attorney specifically notes, “detailed descriptions of ComNet’s Domestic Communications Infrastructure within the United States and its connectivity to operations infrastructure within Hong Kong and China.”

These companies were already in communication with the United States government about security concerns. Yet the FCC’s decision on this reply will be importantly different for a multitude of reasons, including the Trump administration’s general zero-sum hawkishness on China, the broader political climate in Washington around so-called decoupling, and the potential for these Chinese telecommunications suppliers to effectively be thrown out of the United States altogether. The ball is now back in the FCC’s court.

Justin Sherman (@jshermcyber) is a fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Cyber Statecraft Initiative.

Further reading:

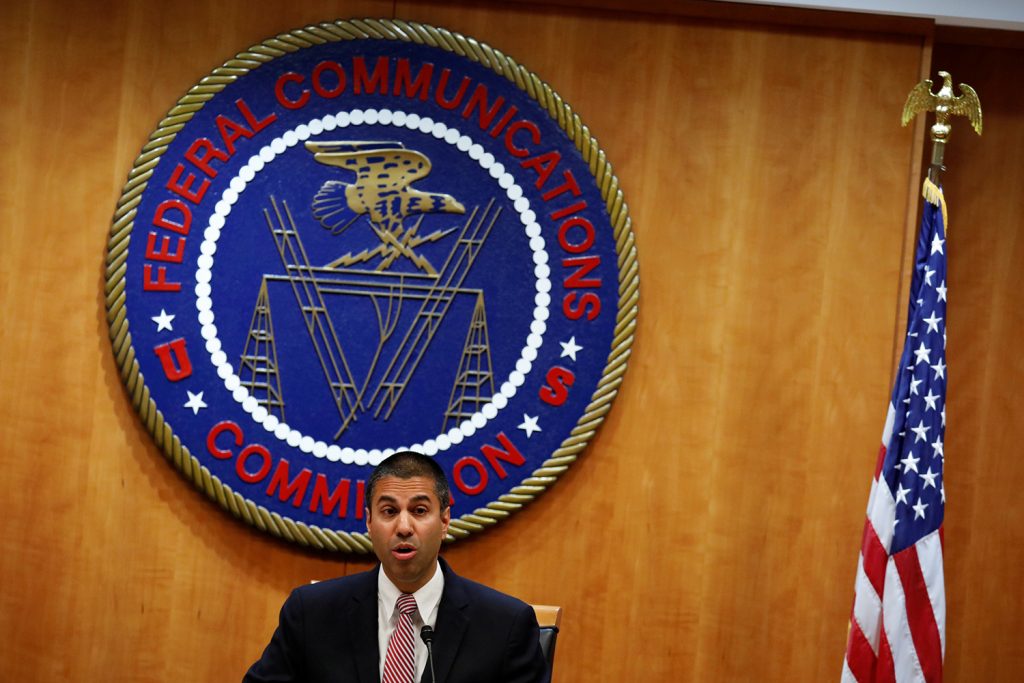

Image: Chairman Ajit Pai speaks ahead of the vote on the repeal of so called net neutrality rules at the Federal Communications Commission in Washington, U.S., December 14, 2017. REUTERS/Aaron P. Bernstein