Amid rising tensions between China and the United States, US Secretary of Defense James Mattis and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo will “attempt to put a floor on the relationship” when they meet with Chinese officials in Washington on November 9, according to Robert A. Manning, a resident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security.

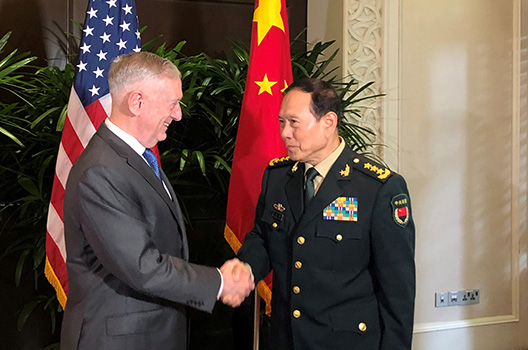

The two US officials will meet Chinese politburo member Yang Jiechi and Defense Minister Wei Fenghe as part of an annual framework to discuss security and political issues. Mattis was supposed to have this meeting in Beijing in October, but Chinese officials postponed it after the United States imposed sanctions on a Chinese company for purchasing weapons from Russia and Washington approved a $330 million military equipment deal with Taiwan.

Shortly after the postponement, US Vice President Mike Pence gave a wide-ranging speech in which he criticized China’s international activity and accused Beijing of “pursuing a comprehensive and coordinated campaign to undermine support for the president, our agenda, and our nation’s most cherished ideals.”

The rescheduling of the meeting in Washington comes as tensions are beginning to decrease between the two powers. US President Donald J. Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping had an “extremely positive” phone conversation on November 2, according to the Chinese foreign ministry. Trump said that both leaders agreed to meet during the Group of 20 (G20) meeting scheduled later this month in Argentina. Hope is also increasing that both sides can work through their deadlock on trade. Chinese Vice President Wang Qishan said on November 5 that China is “ready to have discussion with the United States on issues of mutual concern and work for a solution on trade.”

Robert A. Manning, a resident senior fellow in the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security, discussed the potential agenda for the November 9 meeting and where US-Chinese relations stand now in an interview with the New Atlanticist’s David A. Wemer. Here’s what he had to say:

Q: The November 9 meeting was supposed to be held earlier in October but was postponed by the Chinese. Why are the Chinese willing to meet now?

Manning: China periodically makes gestures to show its displeasure. They were upset at a number of things the United States had done, including the sanctioning of a Chinese military company for its purchase of Russian military equipment, US arms sales to Taiwan, and the acceleration of US military operations in the South China Sea. So they wanted to make a point.

But they also understand that we are the two biggest countries in the world, the biggest economies, and the biggest militaries, and we have to deal with each other. The Pence speech read almost like a declaration of a new Cold War. The meeting may be an attempt to put a floor on the relationship.

Q: What issues do you expect to be on the agenda?

Manning: I think it will be more political and military issues. The military component of the US-China relationship is actually in better shape than most of the rest of it. But I also think that there is a reality, both in air and naval presence, that the US military is now in closer and closer proximity operationally to the Chinese in the East China Sea and South China Sea and that needs to be managed. The United States has signed a number of confidence-building measures with the Chinese—similar to the Incidents at Sea Agreement we signed with the Soviets that allowed commanders on each ship to talk to each other to avoid accidental conflict. The United States signed similar ones with China on maritime and air, but they haven’t been implemented very well.

The Law of the Sea is a treaty that the United States never ratified but adheres to. Yet, China has signed it but is only selectively adhering to it and interpreting it in self-serving ways. China has chosen an interpretation that any ship that goes through its 200-mile economic zone needs to obtain permission from Beijing—that is not the US interpretation nor the majority of the world’s interpretation. So every move the United States makes is a provocation even though Washington sees it as perfectly within its rights of freedom of navigation – a core US interest.

Additionally, China is the largest importer of Iranian oil. The other countries the United States granted sanctions exemptions to—most of them are willing to look for another market to get their oil. But Russia and China are united by a disdain for American hegemony and the way Washington has withdrawn from the Iran [nuclear] deal really makes the United States look like the rogue power Beijing and Moscow paint it to be.

North Korea is another issue. The Chinese are formally adhering to UN sanctions, but 90 percent of North Korean trade is with China and they have quietly loosened enforcement. When President Trump had his [June 12] summit with [North Korean Leader] Kim [Jong-un], the Russians and the Chinese took that as a signal that they could now have a normal relationship with North Korea. The summit also made North Korea’s nuclear program a bilateral issue between the United States and North Korea.

You can’t cut out the frontline Northeast Asian states, particularly China. With them cut out, they have now gone out and made their own deals with North Korea. If the United States is going to get a peace treaty, the Chinese have to be involved. Pompeo has said that North Korea won’t get a nickel of US money in a peace deal, but North Korea wants economic benefits in return for denuclearization. Where are they going to come from? They will need to come from South Korea, China, Japan, and Russia, but they are all now cut out of the diplomacy.

In the past, the United States and China had two big baskets: we cooperate where we can and we try to manage difference. But there has often been a lot more cooperation. Now it is switched. It is a much smaller basket of cooperation and a lot of areas of differences and we are trying to figure out how to deal with them.

Q: The Chinese appear to be more willing to come to an agreement on trade in recent weeks. Do you think trade will come up in the meeting?

Manning: Trade will come up, Pompeo has an interest in that, particularly on intellectual property theft. But the focus of the meeting will be on political-military issues.

Xi has clearly been trying to signal to Trump that he is ready for a deal and I think many in China know that Xi has vastly overplayed his hand. But I don’t know how much the United States is willing to compromise—or if it can take yes for an answer. Trump has already turned down a deal made by Treasury Secretary [Steven] Mnuchin and one made by Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross. Some Trump advisors prefer an economic de-coupling from China.

The stakes are pretty large. We are talking about the two largest economies in the world. US and China trade together count for about 45 percent of all global trade. When people throw these things around about decoupling from China—well that is difficult. Nobody – neither US nor Chinese companies want to be excluded from the world’s largest markets.

I think American leverage has actually been going up due to Trump’s aggressive approach on tariffs. I think a trade deal is possible.

Q: Will Pompeo or Mattis bring up the claims made by President Trump and Vice President Pence that China is interfering in American politics?

Manning: If they have evidence. Everything they have cited so far is dubious. One piece of evidence is these advertising supplements in newspapers that China has been doing for years. If you put that next to what the Russians are doing—I have seen no evidence of the Chinese doing anything close to that.

Then targeting Trump constituencies in their trade tariffs—that is the whole point of a trade war. You want to hurt the other guy as much as possible—and that means politically. The Europeans are doing the same thing, targeting bourbon from Kentucky. If that is their evidence, it is pretty thin and I doubt they raise it.

The Trump administration is also conflating different issues. There are some insidious Chinese influence issues—these Confucius Institutes, trying to shape academic thinking on China—that is a serious issue. There may be more that they haven’t told us, but I would think they would have told us if they had it.

David A. Wemer is assistant director of communications, editorial, at the Atlantic Council. Follow him on Twitter @DavidAWemer.

Image: U.S. Defense Secretary Jim Mattis and China's Defense Minister Wei Fenghe greet each other ahead of talks in Singapore, October 18, 2018. (REUTERS/Phil Stewart)