In the late summer of 1940, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s government faced a dilemma.

British scientists had made a technological breakthrough that could help relieve the growing German military pressure. The cavity magnetron miniaturized microwave radar, making a whole new set of revolutionary military capabilities possible. If Britain could harness this technological innovation it would change the course of the war in Europe.

And here lay Churchill’s dilemma. Isolated and besieged, Britain’s factories were already occupied producing essential supplies. There were no spare resources to exploit the invention or manufacture at scale the capabilities it could provide.

As German pressure mounted in August and September 1940, British scientist Sir Henry Tizzard convinced Churchill to send a mission to North America to share the cavity magnetron—later referred to by American historian James Phinney Baxter III as “the most valuable cargo ever brought to our shores”—and enlist the sleeping giant of US industrial development and manufacturing.

US scientists (working with British and Canadian colleagues) and industry developed and produced dozens of applications of microwave radar. In the short term, air-to-air radar helped Britain detect individual airplanes while air-to-surface radar allowed Britain to preserve its maritime supply lines by detecting surfaced German U-boats. Eventually, microwave radar helped the Allies win the Second World War in Europe.

As the 80th anniversary of the Tizzard Mission approaches, the episode provides a powerful reminder of the importance of manufacturing and supply chain management to the process of capturing innovation. In a defense and security environment characterized—not unlike the 1930s—by a great-power race to harness the military power of new technologies, the United States cannot let efforts to achieve technological superiority outpace the cultivation of an industrial base available to exploit this advantage.

To be sure, the focus across the US Department of Defense (DoD) and the Military Services on new models and creative approaches to driving “innovation” is a salutary development. However, accelerators, trusted capital, procurement reform, technology sprints, and other new tools will only produce desired results if connected to an organized and managed effort to build and sustain the United States’ industrial base, both industry and organic government-owned facilities. Absent this engagement, the US defense community may well ruefully look back on the performance of DoD accelerators to see what it got for its money—and be underwhelmed by how many of its investments transitioned into Service programs of record, and how many opportunities were missed.

Lack of control and oversight over the US manufacturing base and defense supply chain has led to decades of underinvestment in and atrophy of the US manufacturing sector. Single points of failure, dominance of foreign suppliers, and an absence of manufacturing capability in high-tech industries in particular all reveal layers of risks for DoD’s ability to support national defense.

The issue has garnered more attention during the coronavirus pandemic as distressing real-world consequences of this decline are felt, such as shortages of testing, personal protective equipment, and even mundane cleaning supplies. But an excessive focus on the supply chain implications of COVID-19 obscures the broader point that the weak points in our industrial base predate the pandemic and are the result of years of neglect; the problems are structural not situational.

The most frequently cited and easily measured risk associated with the combination of diminished manufacturing and a brittle and vulnerable supply chain is a loss in readiness. For example, a 2019 DoD Inspector General Audit of Navy and Defense Logistics Agency Spare Parts for F/A‑18 E/F Super Hornets found that a lack of supply of spare parts impeded the Navy and the Defense Logistics Agency’s ability to maintain the operational readiness of the Super Hornet fleet.

Supply of combat critical repair parts and spares have always been a challenge and it is hard to build resilience when the number of critical spares on order may not be profitable enough for industry to build a new production line. But DoD now has (or soon will have) the ability to manufacture parts with additive manufacturing built to specification. When does DoD get there? And when it does, will it have the ability to engage industrial partners who can serve as utility infielders capable of adjusting production based on fast-moving requirements?

The effects of a diminished manufacturing base are especially acute during this time of great-power competition in which China-based companies have taken an increasingly prominent role in the US defense supply chain.

In August, defense analysis company Govini released data and analysis demonstrating the scale of China’s infiltration of the US defense supply chain. Examination of a sample from across eighteen core industries revealed that from 2010 to 2019 the number of Chinese suppliers in DoD’s supply chain increased by 420 percent to a total of 655 companies. While none of these companies are Tier 1 suppliers, the scale of reliance on China-based companies in levels 2–5 enhance the risk to the United States’ defense supply chain of manipulation, coercion, and continued intellectual property theft. China-based companies have a conspicuously significant presence in industries such as specialty chemicals, major diversified chemicals, telecommunications equipment, and electronics components, all areas likely to grow in importance as new technologies are developed for defense and security use in the digital age.

Now, more than ever, we need leadership and management of the industrial base. Someone needs to oversee and coordinate innovation efforts and, most importantly, ensure connectivity of Service accelerators and other DoD innovation efforts with the manufacturing base and supply chain. This could be a role for a future DoD chief management officer.

Innovation in Fourth Industrial Revolution technologies is driving military capabilities and conflict in new directions, much like developments in rocketry, atomic science, and microwave radar shaped a new type of warfare in the years leading up to World War II. But creating innovation and capturing innovation are not the same. Even breakthroughs in the most technologically advanced systems—from hypersonic missiles, to flexible hybrid electronics, to autonomous systems and beyond—will prove hollow if the United States does not also possess the domestic capabilities to manufacture and maintain these capabilities at scale and under the duress of an increasingly confrontational geostrategic competition.

Major General John Wharton (retired) is the former Commander of the Army Sustainment Command the Research, Development, and Engineering Command.

Tate Nurkin is a nonresident senior fellow with Forward Defense at the Atlantic Council.

Further reading:

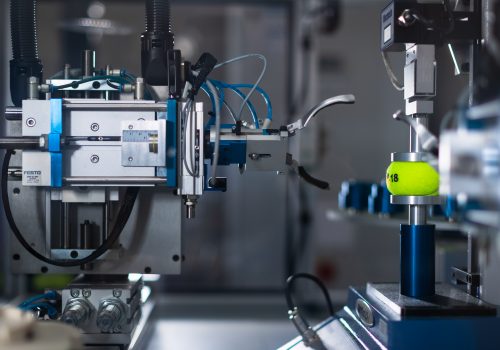

Image: Hand out photo dated July 4, 2020 of an F/A-18E Super Hornet flies over the flight deck of the Navy’s only forward-deployed aircraft carrier USS Ronald Reagan (CVN 76), maintaining Ronald Reagan’s tactical presence on the seas. U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Samantha Jetzer via ABACAPRESS.COM