The Trump administration learned a false lesson in dealing with allies: that pressure works, and that the United States could compel or threaten partners into following the uneven course of its foreign policy. The tactic had diminishing returns. Alliances do not function like rounds of poker. And institutions are not static objects; they are populated by individuals with obligations to each other. Yet such behavior did reveal something more fundamental: the divisive concept of America’s role in a community of nations.

Shifting tone significantly from that of its predecessor, Joe Biden’s team has emphatically pledged to embrace alliances—underscored most recently through appearances by the US president and Secretary of State Antony Blinken at major European Union meetings in Brussels last week. The Biden administration’s preview of its National Security Strategy also points to a new American humility where alliances can become a two-way street.

But in developing that brand, the new team cannot revert to the position where Washington expects to set the agenda, intentionally or otherwise, and our allies seek plausible deniability when signing onto policies championed by the United States. For many of these countries, at least in public, “US ally” has become a dirty word.

“Work with allies and partners…”

If you’ve served in the US government for any administration, you can type this phrase—the beginning of the first talking point in every memo—in your sleep. Work with allies and partners to [fill in the cause here]. Maybe it’s to “hold Russia to account” or “counter unfair Chinese practices.” Those are popular ones. But hidden behind this basic mantra is an unspoken truth: The goal is to get partners to hew to our policy—to see them follow our lead. In practice the phrase doesn’t quite account for the process working the other way around.

As is the case with any country, there’s no shame in the United States advocating for what it wants. But the more honest talking point would be: Convince allies to join us. The onus is on the United States to prove its point, to be persuasive, but not to pretend the policy came from outer space and descended upon US allies. The policy came from Washington.

This American mentality may in part be a product of dynamics in NATO, the prism through which many view US relations with Europe. Not to criticize the greatest military alliance in modern history, but it does show how the United States may be blind to its own privilege. The biggest contributor of military capability and intelligence can often corral the consensus-based organization, which prides itself on decisions “passing silence.” (Translation: Speak now or forever hold your peace.)

But not all security decisions can be reached this way—especially if they involve a broader definition of allies that encompasses global democracies, as the Biden administration’s interim strategic guidance suggests, or require careful diplomacy and a lighter US footprint. The administration’s strategy document also identifies economic statecraft as central to Biden’s foreign policy and expresses the hope that it will play a greater role than the use of military force. As the Biden team works out how it will apply economic statecraft (not an easy task, this author attests), it will discover that “working” with allies and partners may be harder than the dynamic this country finds most familiar.

“If you’re going to pressure us, don’t do it publicly…”

If you’ve delivered your talking points as a US government official, then you’ve received the response above. Understandably, no country’s leadership likes to be fed bitter pills or shamed through the media. But this refrain also tells us something darker and more fundamental: It has become a risky gambit to stand in agreement with the United States.

The team around former President Donald Trump harbored a categorical “you’re with us or against us” mentality; for them, mistakenly, disagreement with Washington somehow meant betrayal. But this wasn’t the first time that an American way of viewing the world in absolute terms—from the communist threat to the War on Terror and now to competition with China—did not necessarily reflect the national-security calculations of partners.

While US leaders often adopt such rhetoric to convey a sense of urgency and the need for sacrifice to the American people, it often smells to partners like a binary choice. And, as smaller powers, they feel they may suffer disproportionately from any blowback for that choice. Hence why allies say that the big ask—the US pressure—should only be made behind closed doors to insulate them from the heat of US doctrine and from their own voters, who view the United States more skeptically than the centrist forces of the political class. It should raise alarm bells when America’s closest allies seek public distance from Washington—when allying with the US becomes a dirty secret, not a source of strength.

“Give us some time…”

European heavyweights are learning that dealing with the American behemoth requires more of the flexibility, responsiveness, and capability that Washington has tried to offer the world in its own image. Many have welcomed Biden with immediate plans for combating climate change, recovering from the coronavirus crisis, and reforming the World Trade Organization.

This all sounds good, but will Washington truly be ready to take a passenger seat? In Brussels last week, Blinken acknowledged that not all European partners could afford to be hawkish on China. But would the State Department and other US agencies then consider that a less openly confrontational approach to Beijing is a European strategy worth emulating if European capitals were to ask for it? Former President Barack Obama is associated with (and occasionally mocked for) the concept of “strategic patience.” Perhaps such patience would tell us that someone else could also have the right answer.

The US needs to sit around the table; the head of the table may not always be the best place. It must also learn to be a policy-taker. Call this approach “common sense” or “multilateralism” or “not doing homework for the world” if it’s more politically palatable that way. Whatever the term, this is how America comes “back,” as Biden likes to put it. This is how the country shows its partners that the United States is not a plywood palace—that its self-renewal is not an empty promise. And this is how foreign leaders can convey to their domestic constituencies that acting alongside Washington is a sovereign decision and not the answer to an American telephone call. Convincing European voters that the world is a dangerous place is, after all, not the primary responsibility of an American president.

In the financial world, the first mover often prevails. But in game theory, the first mover does not always determine the outcome, and foreign policy is much more an intersection of variables than an angel investment. Our allies are more important for the success of our policy than our own policies are for ourselves, and the solutions to the twenty-first century’s transnational problems can only come as the result of true collective action. This will require the Biden administration—and US leaders more broadly—to reimagine the architecture of alliance-building, starting with the talking points.

Julia Friedlander is the C. Boyden Gray senior fellow and deputy director at the GeoEconomics Center. She has served as a senior policy advisor for Europe at the US Treasury Department and as director for European Union, Southern Europe, and economic affairs at the National Security Council from 2017 to 2019.

Further reading

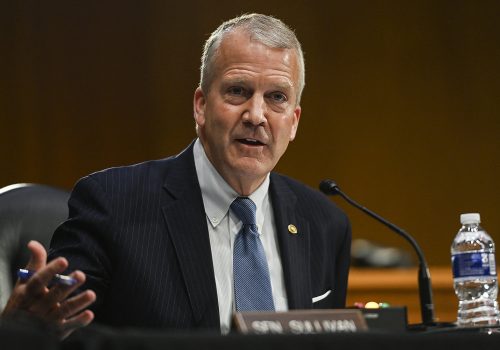

Image: U.S. President Joe Biden (on screen) attends virtual EU Leaders' Summit chaired by President of the European Council Charles Michel (L), in Brussels, Belgium on March 25, 2021. Photo by EU Council via Reuters