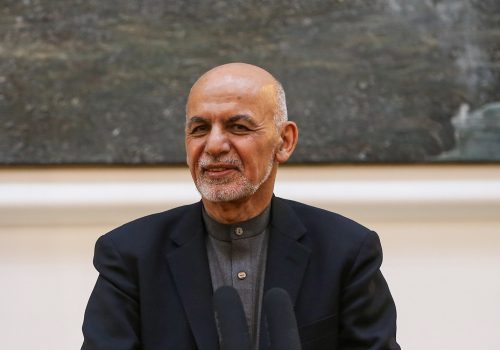

Afghanistan finds itself at a critical juncture as it contends with the coronavirus pandemic and prepares for intra-Afghan peace talks. In an Atlantic Council Front Page event hosted with the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) on June 11, Afghan President Ashraf Ghani joined Atlantic Council President Frederick Kempe, among others, to discuss his vision for peace in Afghanistan. Ghani detailed his country’s ongoing challenges in security, gender equality, and economic development, critical to the peace process, and outlined how the United States and the wider international community can best support the peace process in Afghanistan.

Atlantic Council experts respond to President Ghani’s remarks on the ongoing peace process in Afghanistan:

We have seen this movie many times over in Afghanistan.

“Among the many thoughtful comments by President Ghani, the one that most resonated with me and reflected his vision was when he said, “the war has no winner. All of us are losers in a war. The winner of peace will be the people of Afghanistan and our neighbors. So let’s really work for those whom we are elected to serve or in whose name we claim authority. The people of Afghanistan have a consensus that peace must come and must come soon—and I hope that we can truly muster a sense of urgency to get to that.”

“Returning Afghanistan to its traditional role as a cultural and economic hub for the region will require true commitment and participation of all its neighbors. Iran was totally missing from this exchange. The United States needs to recognize Iran and its potential role in the region. Involving Iran may also allow India to play a more direct trade role in Afghanistan; and Pakistan and India both could then remove the hindrance of potential US sanctions by opening their own trade and energy ties with Iran. Pakistan also remains key to Afghanistan’s overland trade with India. Pakistan needs to see transit trade as more than a zero-sum game. It will benefit greatly from opening that trade route that connects Central Asia via Afghanistan to all of South Asia.

“To use President Ghani’s phrase, we have seen this movie many times over. Let’s pray for a happier ending this time.”

Shuja Nawaz is a distinguished fellow in the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center.

Ghani signals a softening approach to the Taliban.

“Devastated and ravaged by war, Afghanistan has continually suffered due to weak political dispensations and inadequate state resources, mainly due to infighting among the rulers of Afghanistan. The recent political impasse in Afghanistan ended when President Ghani and Dr. Abdullah Abdullah signed a power-sharing deal. In his conversation at the Atlantic Council, President Ghani described the truce as an important step towards peace and stability in Afghanistan.

“While it is too premature to attach hopes and expectations over the continuity of this arrangement, these words from President Ghani come at a critical time as the Afghans prepare for the next phase of the Afghan peace process: Intra-Afghan dialogue. During his talk, President Ghani announced that the government would soon release two thousand Taliban prisoners, while calling Taliban a “reality in Afghanistan.” Taken together, these statements indicate a softening stance and approach towards the Taliban, something that could be a boon for the much-awaited dialogue between the government in Kabul and the Afghan Taliban.

“President Ghani’s remarks on foreign policy were instructive to say the least. While stressing the need for multi-alignment, the president outlined his commitment to ensuring that his country’s territory is not used for violence against neighbors and friends. This, coupled with his argument that Afghanistan must strive to become the hub of regional connectivity, signaled that the Afghan polity realizes the importance of peace and the cost of conflict. In regard to foreign policy, President Ghani’s comments on the Pakistan Army Chief’s recent visit to Afghanistan are noteworthy—the president said that Afghanistan and Pakistan are more closely aligned at this stage than they were before. This view is a significant departure from his recent insinuations against Islamabad, which had marred relations. That all sides are now seeing Pakistan as an enabler of peace is a healthy sign. That said, it remains to be seen how these encouraging words are turned into conciliatory measures on ground. These glad tidings bring with it an offering for all stakeholders with hope for peace, stability, and prosperity for not only Afghanistan but the entire region.”

Dr. Rabia Akhtar is a nonresident senior fellow in the South Asia Center.

Considerable gap remains between Ghani’s vision and the Taliban’s.

“For Afghanistan, the past months have been extremely difficult, with the government and people facing simultaneous security, political, and COVID-19 crises. President Ghani’s June 11 discussion with the Atlantic Council and USIP was relatively optimistic, reflecting a renewed sense of possibility in light of the successful Eid ceasefire, hopes for continued reduction in violence, and the resolution of the political dispute with Dr. Abdullah (“we are keen to work together”) which opens the way to the possible initiation of peace talks and improves the relationship with Washington. Ghani announced his government’s decision to soon complete the release of the five thousand Taliban prisoners promised in the US-Taliban agreement, a bold decision demonstrating commitment to peace, his “absolute priority.” His hopeful assessment to the just-concluded visit by Pakistan military Chief of Staff Qamar Javed Bajwa (“closest alignment with Pakistan in terms of discourse”) and his focus on “multi-alignment of our foreign policy” and expanding regional partnerships all seem intended to increase momentum, coupled with Ambassador Khalilzad’s untiring diplomatic efforts, for a ceasefire and getting the Taliban to the negotiating table.”

“While hinting there might be early movement on the negotiations front, President Ghani put down markers on the role women will play in his administration and in peace negotiations, that the relationship with the US should be based on partnership with “mutual interests and respect,” and that his goal is “peace as soon as possible, but a sustainable peace.” His observation that the United States and Afghanistan are “completely aligned” on the negotiated “end state of a sovereign, democratic, and united Afghanistan at peace with itself and the world” indicates the considerable gap between his vision, the vision of most Afghans, and that of the Taliban, which continues to message its commitment to restoration of the Islamic Emirate.”

James B. Cunningham is a nonresident senior fellow in the South Asia Center and former US ambassador to Afghanistan.

Peace cannot be achieved with an unreasonable timeline.

“President Ghani’s pragmatic approach to the peace efforts on the heels of potential direct talks with the Taliban is commendable. His principled stand to negotiating a “just” peace has been consistent all along, and he has repeatedly demonstrated, in his actions, his sincerity and willingness to make hard trade-offs and compromises instead of sticking to fixed positions. Neither has he shied away from paying the “price” necessary for realizing peace, nor has he succumbed to significant pressures to (over)pay for an impermanent deal that could well prove to be overvalued. But despite the uptick in violence, Ghani has remained publicly accommodating of the Taliban in the hopes of moving the process forward.

“What has been done so far is good enough, but what matters now is to address the underlying challenges the process faces ahead. This includes the continuing concerns regarding the lack of a meaningful intra-Taliban consensus to negotiate peace, one likely to upset the upcoming process should the Taliban make unreasonable demands to please their hardliners. Meanwhile, the current regional consensus about Afghan peace, though significant, is quite tenuous, especially considering the unrestrained hedging behavior of regional players. Most important of all, none of these efforts would matter should US President Donald J. Trump decide to pull the plug on Afghanistan. That is why expectations to reach an outcome in an unreasonable time frame that is favorable to all parties—including one that caters to Trump’s urgent political desires—should be moderated.”

Javid Ahmad is a nonresident senior fellow in the South Asia Center.

Taliban disunity could still play spoiler.

“At the forefront of Afghan President Ashraf Ghani’s vision for peace in Afghanistan are democracy, regional connectivity, and multi-alignment. Women’s and minority rights are also very much a part of it. The big question is whether he will be able to implement his vision. The challenges are plenty. Among the significant ones today is not just the willingness, but also the ability, of the Taliban to negotiate as a united whole. The COVID-19 pandemic has affected its top leadership, and a factional war may ensue. In the conversation, President Ghani called for a humanitarian ceasefire. But there may be some within the Taliban who could turn to violence to secure or even improve their standing within the organization. As President Ghani forewarned, “irreconcilables and spoilers should not be given an opportunity” to derail the peace process.”

Dr. Yelena Biberman is a nonresident senior fellow in the South Asia Center.

Ghani provided a window into the complexities of the peace process.

“Speaking to an audience of mostly Washington pundits hosted by the Atlantic Council and USIP last week, Afghan President Ashraf Ghani, pledged that—in what seems as a quid pro quo with the Trump administration—he is taking necessary steps to complete the release of five thousand Taliban prisoners within days in order to open the door to talks with the Taliban as part of a highly complex and, as-of-yet, murky process.

“At a time when Afghanistan is hit by growing fatalities caused by war and COVID-19, the White House is once again intending to review Afghan drawdown options. As countries near and around Afghanistan are recalibrating their geopolitical positions, Ghani expressed preference for a “time-bound and conditions-based” US withdrawal schedule tied to a political settlement of the nineteen year-long conflict that he hoped would assure a “democratic and constitutional” order and foreign policy “multi alignments.”

“Taking cues from Afghanistan’s troubled history and ahead of imminent political talks with the Taliban (if and when all conditions are met), the Afghan president used the occasion to outline a bureaucratic process framed around a mix of multi-prong vision and policies that he may use as negotiating talking points or as redlines that could either help or complicate future intra-Afghan deliberations if the participants fail to agree on a common agenda or step-by-step approach on deliverables leading to a possible new power-sharing outcome.

“When asked by a journalist whether he was willing to step aside to allow an interim government to pave the way for a transitional period, Ghani telegraphed diverse messages to different constituencies by confidently stating that “any discussion of an interim government is premature… I serve at the will of the Afghan people, not at the will of the Taliban.” He then offered a controversial historic analogy of former communist era leader Mohammad Najibullah who, according to the current Afghan leader, “made the mistake of his life [prior to his downfall in 1992] by announcing that he was going to resign.” Ghani stressed, “please don’t ask us to replay a film that we know where it goes.” Najibullah was part of the Soviet-backed regime that fought the US-backed anti-communist insurgents from 1978 to 1989.

“While aiming to control the war and peace narratives from his side, Ghani also expressed a desire to manage the end-state of political talks. However, facing an uphill battle, several challenges and unknowns are lining the perilous path to what he termed “sustainable peace.” Ghani also asked that a Loya Jirga (traditional grand assembly) ratify a final agreement as a legitimizing step, an issue that has not been brought up by any other Afghan stakeholder yet.

“Reassuring his American audience, he stressed that “now we are on course,” adding, “the people have consensus that peace must come soon,” and that “the United States and Afghanistan are completely aligned.” However, pointing several times to “turbulence and uncertainty,” he conveyed the urgency that based on “mutual interests,” his side cannot lose the minimal support and funding levels that the current US administration would need to provide to sustain his government as part of new US policy decisions.

“Heralding a substantial reduction in American blood and treasure since he became president in 2014, Ghani vowed to use the Afghan commando forces and Air Force as “key pillars of survival and ensuring constitutional order.”

“With the US-Taliban agreement stipulating a withdrawal date of May 2021 and discussions underway to, maybe, expedite the drawdown prior to the November US presidential elections, the Afghan peace process may face a timelines dilemma because no one realistically expects negotiations to end within the established timeframes.

“Although there are accelerated efforts by various players, including many international stakeholders, to get the intra-Afghan talks off the ground within the next few weeks, it is still unclear at this stage how fast US and other mediation efforts can help the Taliban and Kabul come to terms about the initial meeting, which may end up being more of a greet-and-meet photo-op than a negotiating session.

“What happens thereafter will be more consequential as intra-Afghan talks are expected to address the thorny ceasefire issue and discuss a joint agenda leading to complex negotiations over the future of the country. Pre-conditions and redlines may help extract concessions at times, but they can also hinder talks or polarize the deliberations, especially if the exchanges are not professionally moderated by a credible and impartial actor.

“Overall, the Washington interaction, the first since Ghani started his second term in March, was not only an opportunity to address pundits and policy wonks in a key capital city, but also a window on the complexities, political options, and strategic choices that could make or break the first serious opportunity in more than four decades to end America’s—and Afghanistan’s—longest war.”

Omar Samad is a nonresident senior fellow in the South Asia Center and former Afghan ambassador to France and Canada.

Further reading:

Image: An Afghan man sells protective face masks during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak in Kabul, Afghanistan June 18, 2020. REUTERS/Mohammad Ismail