The accepted historical narrative of the Cold War is that US President Ronald Reagan, ever steadfast in his condemnation of the “evil empire,” won that great geopolitical standoff.

But in reality, it ended only when Mikhail Gorbachev, who died this week at age 91, folded a weak hand. If any other leader had been inside the thick red brick walls of the Kremlin during those years, it might have been impossible for such scant blood to have been shed.

“He was a hawkish person,” Gorbachev recalled to me during Reagan’s 2004 funeral, which I covered for the New York Times. But that did not stop the last Soviet leader from engaging with a strategic enemy, one who would later become his friend.

Amid his triptych of reforms to save the Soviet Union from itself—glasnost, perestroika, and uskoreniye, which old Moscow hands translated ironically as “open it up, shake it up, and speed it up”—Gorbachev could not have predicted that he would share in ending the nuclear suicide pact between Moscow and Washington. He never dreamed of the dissolution of the Soviet Union or the destruction of the Communist system. He remained a loyal party man and simply believed, wrongly, that the party could be fixed.

Perhaps it was Reagan’s initial hardline posture that brought Gorbachev around. Anyone who lived in or reported from Moscow in those years (as I did, for the Chicago Tribune) remembers keenly how the Kremlin propaganda machine went into overdrive denouncing Reagan’s weapons build-up as dangerous and destabilizing.

In truth, the Soviet leadership was less afraid of being bombed back to the stone age than of being outspent back to the stone age. The Soviet Union may have been able to produce a world-class attack helicopter, but it couldn’t pave the streets around the Kremlin or guarantee ample supplies of fresh fruit to its population year-round. Military de-escalation with Washington was an economic necessity if Gorbachev’s domestic reforms were to work.

When I asked him about the many obituaries of his former US adversary that included repeated accolades about Reagan winning the Cold War, Gorbachev paused, then spoke again in that recognizable (and sometimes caricatured) southern Russian accent of his native Stavropol.

“He had the foresight and the wisdom and the commitment to step over all of that, and start changing relations with the Soviet Union,” Gorbachev said. “We had the same wish, and we were able to do that.”

But, Gorbachev repeated, “He, himself, could not have changed the situation alone.”

The late Soviet leader was the essential partner, basing his new thinking on Soviet policy around the idea that cooperation with Washington, not confrontation, was the key to pushing ahead with his reforms at home. In the months before revolution swept Eastern Europe and the Berlin Wall came down, Gorbachev would not give his blessing to quashing protests with force. After all, cutting loose the increasingly unmanageable Warsaw Pact would ease a huge strain on the Soviet budget.

In the end, his decisions amounted to a strategic Kremlin retreat from Eastern Europe and led to the eventual collapse of the Soviet Union itself. Gorbachev did that, not Reagan.

Now just imagine that the Kremlin’s negotiator with Reagan had been Vladimir Putin—a man who maintains that the collapse of the Soviet Union was the “greatest geopolitical tragedy of the century,” ignoring even the Holocaust. Collaboration to create a calmer global order, or a return to one, seems like it would have been impossible with him in power at the time.

Last week, Ukraine marked the thirty-first anniversary of its vote for independence, which came after Kremlin hardliners failed to topple Gorbachev in a coup. It was one of the most inspiring stories I ever covered. Today, Putin—who drives toward the future with one eye, and maybe both, on the rear-view mirror—is seeking through military force to rewrite that exact moment of history.

To Putin, and sadly to most Russians, Gorbachev’s legacy is not one of democratization, personal freedom, and a better life; it is chaos, collapse, and economic turmoil (catnip for an old-school Kremlin propagandist). To many Russians, the glasnost was not just half-empty, but completely empty of promises fulfilled.

In his interview with me, Gorbachev also offered a brilliant metric for assessing any negotiation.

Victory, success, and a positive outcome, he said, can only be found when all parties feel they have won something. Even if Reagan did claim victory in the Cold War, Gorbachev believed he’d bought time for his radical restructuring of Soviet society and the economy to take root.

Unfortunately, the course he charted toward a brighter, more democratic future was cut short. But while history may not have been kind to Gorbachev, our memories should be.

Thom Shanker is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security and the director of the Project for Media and National Security at George Washington University’s School of Media and Public Affairs. He served as Moscow correspondent for the Chicago Tribune, covering Gorbachev’s ascent to power through the collapse of the USSR, and later worked for the New York Times for twenty-four years as a national security reporter and editor.

Further reading

Tue, Aug 30, 2022

What legacy does Mikhail Gorbachev, the last Soviet leader, leave behind?

Experts react By

Our experts examine Gorbachev's complicated legacy and wonder: What could have been?

Tue, Aug 23, 2022

Six months, twenty-three lessons: What the world has learned from Russia’s war in Ukraine

New Atlanticist By

Our experts break down how this conflict has transformed not only military operations and strategy, but also diplomacy, intelligence, national security, energy security, economic statecraft, and much more.

Tue, Aug 23, 2022

A strong Ukraine is the best solution to Europe’s Russia problem

UkraineAlert By

Ukraine's courageous response to Putin's invasion has inspired the world but some Western leaders remain in denial over the threat posed by a hostile Russia, writes Ukrainian Defense Minister Oleksii Reznikov.

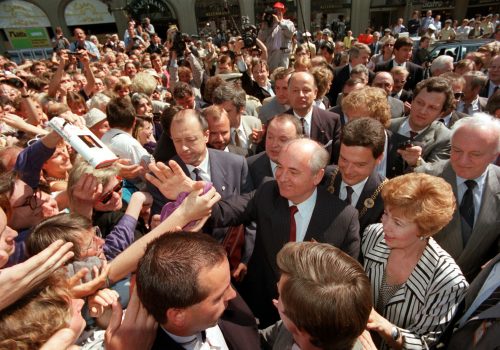

Image: Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev is welcomed to the White House in Washington, DC, by US President Ronald Ronald Reagan on December 8, 1987. Photo by Arnie Sachs/CNP/REUTERS