Amer turns the pages of a book. He is sitting in the hallways of an underground library where he creates a world for himself far away from the outside world above. Holding a copy of Commentary on the Mu’allaqat, he explains that he feels that his soul is full of poetry. Despite the sounds of war outside, the characters of the poems leave the pages and excite his imagination, taking him to another place. In this way, he can ignore the shelling and death that surround him.

Amer turns the pages of a book. He is sitting in the hallways of an underground library where he creates a world for himself far away from the outside world above. Holding a copy of Commentary on the Mu’allaqat, he explains that he feels that his soul is full of poetry. Despite the sounds of war outside, the characters of the poems leave the pages and excite his imagination, taking him to another place. In this way, he can ignore the shelling and death that surround him.

The idea of establishing a library in Darayya began by accident, and as a form of resistance. Due to the intensity of the bombardment of Darayya by the Syrian regime’s forces, there was a group of young men who, once the pace of the bombardment had slowed, would go to the affected areas to help evacuate the wounded and bury the dead. In such circumstances, the remains of the books called to them. One of them in particular, Ebada (nicknamed Abu al-Bara’a), realized that these books were his only way to access the knowledge and culture that he had been deprived of by the war.

Ebada recalls that he would go to houses that had been shelled and would sit among the rubble to read some books. He began to feel a kind of addiction. Thus, just as he would search for the deceased among the rubble, he would search for books, hoping to find one of his favorites.

Ebada states that, in a besieged city that has experienced all types of bombardment, entertainment is almost nonexistent. He is a book lover, but he also finds reading to be a sort of revolution because it expands the mind and exposes it to new perspectives.

The process of collecting the books began as an individual initiative: the young men would take the books, record the names of the owners of the houses in which they were found, then move them to a relatively safe place. However, with the young men of the city’s strong belief that the war would not end soon, they began to think more seriously. Thus, this individual initiative became a joint initiative. The initiative was shared among intellectuals trapped in the besieged city, the young men who had been forced to leave their university studies, and some Free Syrian Army (FSA) fighters.

The idea was to create a life apart from the death and destruction in the city. First, it was necessary to look for a relatively safe place to put the books. In March 2014, the young men proposed the idea to a basement floor owner, in a building somewhat distant from heavily shelled areas, about using his space to preserve the books they had found and to create a library in house the books. The owner of the basement had left the city, but he agreed to contribute the space. A few of the young men self-financed preparing the space and also gathered wooden planks to build bookshelves. They made use of the work of a number of carpenters in the city, who also participated in the initiative by sharing some of their leftover materials.

Amer remembers perfectly the first day the library was completed. There were dozens of books strewn across the wooden shelves in the former basement. Over time the young men put more and more time into maintaining the space and found themselves immersed in the project. The library gave them some relief from the monotony of war and constant bombardment. In safety of the library, it gave them a taste of normal lives they should have been leading were it not war.

Most of the young men that volunteered with this project had been forced to abandon their university studies. Amer, for example, was unable to complete his studies in Arabic literature at Damascus University. As the number of books on various subjects increases, the emptiness these young men feel decreases. They have even read about indexing and classifying books and have begun to implement what they learned, even if they do so in a rudimentary manner.

When you enter the library, you find the entrances fortified with sandbags, which the civil defense team in Darayya helped to put in place. The library was previously lit with candlelight most of the time, until the building adjacent to the library agreed to supply the library with electricity via a generator. Now, for those that work in and visit the library, it has become a real place. It has transformed from a dream that excited the imaginations of young men and children into a reality.

Regarding the relationship between the FSA and the library project, Amer states, “Many of the early volunteers collecting books were Free Syrian Army fighters, just as many of the library’s visitors were from the Free Syrian Army. Luckily for us, there are no other brigades, so we are not disturbed. On the contrary, they were among the most important elements that made the project successful. They are from this land, they know its nature, and its people. They inform us of the areas that will be bombarded and, in many cases, provide us with books.” The local council lent the young men the necessary tools to transport the books and build the shelves. It also encouraged the young men to volunteer for and pursue this project. It was among the most prominent contributors to the project in terms of morale and, in many cases, logistics.

The question of what society will gain from this library never occurred to Ebada because it began, according to his description, as a one-off activity. However, as the project grew it quickly developed a wider social dimension. Young people gather in the library, especially during periods of increased bombardment, looking for a haven not only from war, but also from depression and hopelessness. It has become a participatory atmosphere: young people have formed a book club, where they gather for discussion after reading a specific book. One of the most read books is the novel The Alchemist by Paulo Coelho. There is a wide interest in different books and subject matters that varies depending on the person and the availability of books.

Ebada said, “A few months after the library’s launch, the residents stopped permitting the reading of books in the library itself. Thus, we established a preliminary system for lending books, based on the name of the book, the name of the person who borrowed the book and the date. The matter was not always smooth as our ability to focus on this project is inversely proportional to the siege and the bombardment of the city.”

“Those most affected by war are the children,” explains Ebada. “Naturally, that’s what we noticed in our lives here. For this reason, we have tried to interact with them more, through reading sessions and workshops or even beautiful readings of children’s stories, so that they look like a play. In this place, children have found the best space to reintegrate themselves into a world that they had begun to feel exiled from, especially as schools cannot open for more than two hours a day due to the constant bombardment. That’s why people don’t send their children to school. However, because these activities take place in the library, for a short period of time and during times of relative quiet, families have been supportive of the idea. Occasionally, they have even participated in some of the readings or borrowed books and done these activities at home. This encouraged us to remain committed. For this reason, we took the initiative of holding classes based on the needs of the community around us. We found that there is a need to learn English and to eradicate illiteracy among seniors, so we started doing these things. However, we have had to stop many times because of the poor security situation.”

The truce that was agreed upon in February 26, 2016 had a significant impact on Darayya. The young men and women began to expand their activities, including searching for books among the rubble, recalling borrowed books, trying to air-out the books and working towards a more accurate and comprehensive system of classification. However, with the return of violence, it is expected that the atmosphere of war will also return, as well as the monotony of a life of shelling and destruction.

Rahaf Habboub is a Syrian journalist.

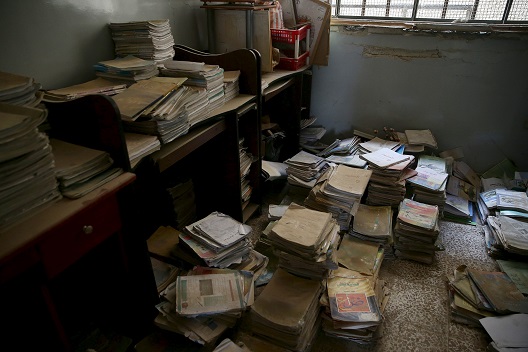

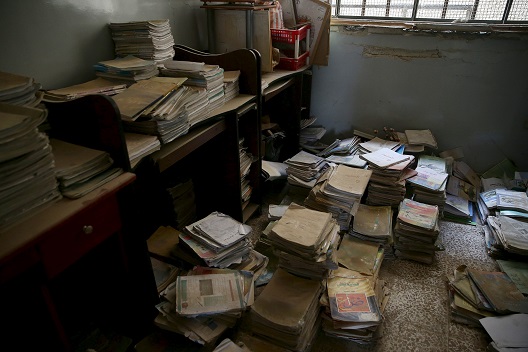

Image: Photo: Books covered in dust are pictured inside a school in a rebel-controlled area of the eastern Ghouta of Damascus, Syria October 19, 2015. REUTERS/Bassam Khabieh