Imagine if, in 1945, the War Department and senior American commanders in Europe and Asia had been permitted to define victory simply as the fall of Berlin and Tokyo, with no post-combat stabilization and reconstruction program for either Germany or Japan. Imagine if, in 2003, the United States had invaded Iraq without a realistic, implementable plan for governance after the fall of Baghdad and Saddam Hussein. Imagine if the West had fought Qaddafi in 2011 without much thought given to what would replace him. In fact, no imagination at all is required for the cases of Iraq and Libya. Both operations were undertaken with no serious regard to what would follow. Both produced disaster.

Imagine if, in 1945, the War Department and senior American commanders in Europe and Asia had been permitted to define victory simply as the fall of Berlin and Tokyo, with no post-combat stabilization and reconstruction program for either Germany or Japan. Imagine if, in 2003, the United States had invaded Iraq without a realistic, implementable plan for governance after the fall of Baghdad and Saddam Hussein. Imagine if the West had fought Qaddafi in 2011 without much thought given to what would replace him. In fact, no imagination at all is required for the cases of Iraq and Libya. Both operations were undertaken with no serious regard to what would follow. Both produced disaster.

In the campaign to defeat ISIS (ISIL, Daesh, Islamic State) in Syria, the US Department of Defense and Central Command (CENTCOM) think they have a formula for addressing the “what’s next” question in a way that evades and transfers responsibility entirely. They have defined their mission and that of the American-led, anti-ISIS international coalition, as one of supporting indigenous “partner forces:” in this case a Syrian-Kurdish-dominated militia (the “Syrian Democratic Forces”) top-heavy with Syrian Arab auxiliaries. “Partner forces”—featuring Kurds with close ties to the terrorist PKK—are the ones who have been handed responsibility for what happens on the ground once predominantly Syrian Arab areas are liberated from ISIS. American military aviation and special forces on the ground are only there to “support,” don’t you know.

The theory behind entrusting post-ISIS stabilization to a Kurdish-led militia, one trained and equipped by the United States, is that indigenous forces are much better suited for the task than foreigners. As former Secretary of Defense Ash Carter noted in a recent Washington Post op-ed, “History has shown this task is difficult for outsiders to accomplish.” Indeed, Douglas MacArthur and Lucius Clay would not have minimized the difficulties. Yet even they upheld the central post-combat principle of military civil affairs by drawing to the maximum on indigenous elements for policing, schooling, utilities, public sanitation, and the like. What, one might ask, does any of this have to do with autonomy-seeking Kurds operating militarily in Arab towns and cities?

Indeed, the reach of a Kurdish-dominated militia does not extend very far south in the Euphrates River Valley, where ISIS has ensconced itself. CENTCOM knows that its “partner forces” may be limited to the capture of Raqqa, ISIS’ self-proclaimed capital. It has therefore invited the Assad regime and the Iranian-led Shia foreign fighters supporting that regime to help themselves to the rest of eastern Syria so long as they shoot at ISIS and avoid targeting “partner forces.”

CENTCOM’s finding that the restoration of Assad rule in eastern Syria—supported decisively by Iran—would contribute to the victory over terrorism and extremism is odd. Assad and Iran have been instrumental in the rise of ISIS. Does the definition of “indigenous” extend to Afghan, Iraqi, Lebanese, and Iranian fighters? Is it possible that ISIS in its current Syrian configuration is seen in Tampa as the sum total of the extremism problem? Apparently so. CENTCOM defines its mission in Syria simply as one of killing ISIS. Keeping it dead would be someone else’s job.

The evasion and transfer of post-combat stabilization responsibility for Syrian areas liberated from ISIS is self-defeating. But it may well be a fait accompli. In a system where few able-bodied young Americans give even passing thought to serving their country in uniform, it is inevitable that military leaders will define-down military missions to the extent they can. Vesting post-combat stabilization responsibilities in a combination of hired hands in Raqqa and terrorist-abetting mass murderers elsewhere may be of no consequence to those who would define victory in eastern Syria as “beat ISIS and devil take the hind-most.” But the potential consequences for American national security and that of allies and partners in the region and beyond are frightening. The stage may be set for variants of Islamist extremism far more capable than today’s ISIS to arise.

This writer has pressed relentlessly since 2015 for the United States to organize and lead a professional ground force coalition of the willing in eastern Syria to defeat ISIS sooner rather than later, and to work with genuine local leaders and anti-Assad opposition figures—many of whom had received material American support—to establish competent, humane, and inclusive post-ISIS governance. Yet this kind of heavy diplomatic lifting attracted no support in the Obama White House. When three Gulf states volunteered forces to fight ISIS, the Obama administration dove for cover. When the Syrian opposition offered a plan for making eastern Syria a model for the transitional governing body called for by the June 2012 Geneva Final Communique, Obama administration officials discovered a fascination with their shoe laces.

Now the Trump administration finds itself doubling down on and justifying a policy that may keep ISIS or a more capable successor alive and breathing even as the body of the ersatz caliph rots. It may be too late to undo that which has been pursued with single-minded, stubborn determination for the better part of three years. Perhaps we have indeed discovered a new and effective way of waging war in faraway places, using “partner forces.” But responsibility for sealing the victory cannot be subcontracted or assigned without inviting dire consequences. There would, after all, be no war to liberate eastern Syria from ISIS had the United States not launched and sustained it.

In the end, post-combat responsibilities can indeed be evaded. They can be handed off to militiamen or ignored altogether. But the consequences of this evasion, as demonstrated in Iraq 2003 and Libya 2011, can be catastrophic.

Frederic C. Hof is director of the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East.

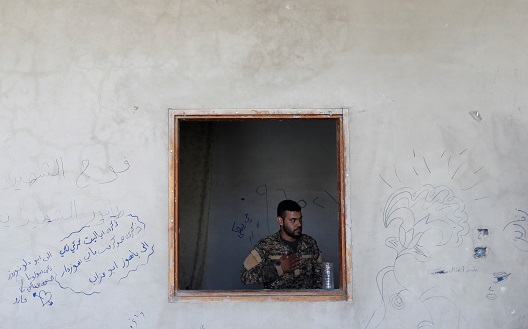

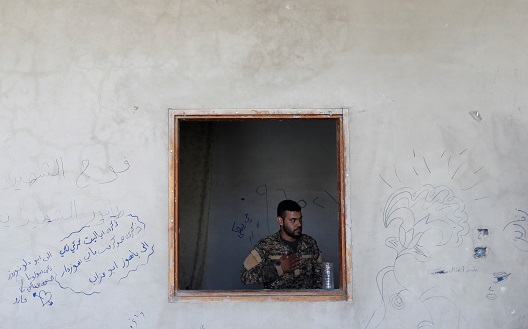

Image: Photo: A Kurdish fighter from the People's Protection Units (YPG) gestures in a house in Raqqa, Syria July 2, 2017. REUTERS/Goran Tomasevic