Lebanese Hezbollah was founded on the doctrine of resistance against Israel. Since at least 2012 however, the Shia militia has fought in neighboring Syria on Iran’s behalf to secure the survival of Bashar al-Assad’s regime and thereby maintain its own overland corridor to Tehran. Though it has succeeded, along with Iran and Russia, in stabilizing the Assad regime, it has sustained considerable losses. A study of those losses provides valuable insights into Tehran’s strategic thinking and tactical considerations of the Hezbollah leadership which are bound to have considerable implications for regional security dynamics.

Lebanese Hezbollah was founded on the doctrine of resistance against Israel. Since at least 2012 however, the Shia militia has fought in neighboring Syria on Iran’s behalf to secure the survival of Bashar al-Assad’s regime and thereby maintain its own overland corridor to Tehran. Though it has succeeded, along with Iran and Russia, in stabilizing the Assad regime, it has sustained considerable losses. A study of those losses provides valuable insights into Tehran’s strategic thinking and tactical considerations of the Hezbollah leadership which are bound to have considerable implications for regional security dynamics.

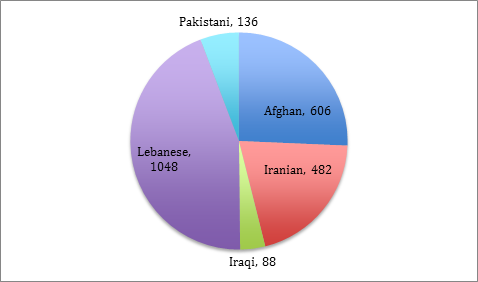

According to a survey, Arabic language public (including but not limited to Arabi Press) coverage of funeral services held in Lebanon, a total 1048 Hezbollah fighters were killed in combat in Syria from September 30, 2012 to April 10, 2017, or almost half of the total Shia combat fatalities. This number however, must be treated as an absolute minimum, since the Hezbollah leadership has every reason to downplay losses. Giving full information on number of killed would increase domestic (Lebanese) resistance to Hezbollah’s involvement and reveal more information about its forces to its adversaries.

Figure 1: Afghan, Iranian, Iraqi, Lebanese and Pakistani Shia combat fatalities in Syria January 2012 – April 2017

Of these Hezbollah fighters, 60 were identified as al-Qaid al-Shahid (martyred commander) or al-Qaid al-Maydani (field commander), which distinguishes them from the rank-and-file members of the Shia militia.

Hezbollah is extremely secretive about where exactly these fighters died in Syria: Among the 1048 known combat fatalities, the place of death of 143 is known – often from Iranian websites and Syrian opposition sources. (Figure 2)

Figure 2: Hezbollah combat fatalities and place of death in Syria January 2012 – April 2017

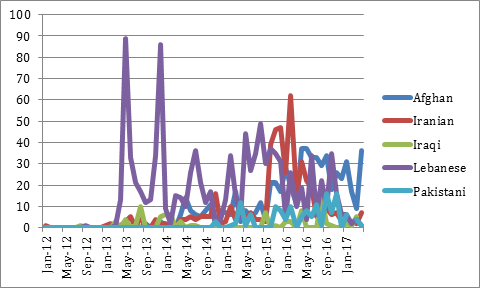

However, fluctuations in Hezbollah and allied Shia militias combat fatality rate in Syria correlate with major combat operations in that country.

Figure 3: Afghan, Iranian, Iraqi, Lebanese and Pakistani combat fatalities and month of death in Syria January 2012 – April 2017

While the December 2013 peak in Hezbollah fatalities shown in figure 3 is misleading because the public sources announced nearly a hundred fatalities all at once (even though the actual month of death/burial for many of them occurred earlier), other peaks coincide with major combat operations reported in the press:

- In May 2013, Hezbollah and the Syrian army launched a joint offensive against the city of al-Qusayr, a city strategically located between Damascus and the Mediterranean coast and close to the Lebanese border.

- Although there is no record of Hezbollah operations in July 2014, the increased fatalities that month (36 fighters) coincided with the Islamic State’s (ISIS, ISIL, or Daesh) seizure of the Shaer gas field in Homs governorate on July 17, and its capture of the 17th Army Division’s base near Raqqa on July 25, suggesting that Hezbollah forces played an important role. In comparison, 270 people were killed from the Syrian government forces, at least 200 of which were executed after being captured.

- The February 2015 fatalities likely reflect the joint offensive by Free Syrian Army forces and the al-Qaeda affiliated Nusra Front against Hezbollah strongholds in western Qalamoun, near the Lebanese border.

- The high monthly fatality rate in the last half of 2015 (217 deaths from July-December) includes the battle for al-Zabadani in July, but also marks the run-up and aftermath of the first Russian air campaign in Syria, which began on September 30 of that year and ushered in a period of increased offensives by regime forces and their allies.

- The hard June, August, and October 2016 battles in the suburbs of the besieged city of Aleppo is reflected in the Hezbollah death toll.

Fluctuations apparent in Figure 3 provide valuable insights into Tehran’s strategic thinking. From the beginning of the protests in Syria, Tehran never wavered in its support for its Syrian ally in Damascus. However, Tehran initially shied away from large scale deployment of Iranian forces in Syria and clearly preferred to deploy Lebanese Hezbollah forces. For a while, Lebanese Hezbollah also denied the presence of its forces in Syria, only admitting its engagement when it could no longer hide its rising death toll from the public.

It was Hezbollah’s high mortality rate in the prolonged war that forced Iran to deploy the IRGC and allied Shia militias in Syria. Hezbollah must balance between deploying its forces in Syria and maintaining its domestic presence. The Shia militia faces domestic opposition in Lebanon: the end of the civil war in Lebanon did not translate into disarmament of the involved parties and militias, and significant weakening of Hezbollah forces could tempt other armed militias in Lebanon to challenge the Shiite militia’s dominating position in that country.

Hezbollah also faces formidable challenges south of the border: Israeli Air Force has on several occasions bombed arms transports from Syria to Lebanon, and the Hezbollah leadership cannot disregard the risk of Israel Defense Force taking advantage of the Shia militia’s engagement in the Syrian civil war to attack Hezbollah positions in Lebanon. This risk becomes more prevalent as Hezbollah builds up its arsenal and Israel feels threatened.

While stabilization of the Bashar regime demonstrates the capacity of Hezbollah as a useful proxy for Iran, the fragile balance of power within Lebanon, Hezbollah vulnerabilities when facing Israel, and the need for larger scale deployment of IRGC and allied Shia militias in Syria, clearly show the limits of Hezbollah’s capabilities.

Ali Alfoneh is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council.

Image: Photo: Supporters of Lebanon's Hezbollah leader Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah react as one carries his picture during a public appearance by Nashrallah at a religious procession, one day before the Shi'ites will mark the day of Ashura, in Beirut's southern suburbs, Lebanon October 11, 2016. REUTERS/Aziz Taher