Russian-Iranian cooperation in Syria is booming today, with support for the Syrian regime making it far superior to opposition forces. After the fall of Aleppo two years ago, the opposition appears on the verge of losing another important area, Eastern Ghouta—a highly strategic area due to its proximity to the heart of the capital city, Damascus.

Russian-Iranian cooperation in Syria is booming today, with support for the Syrian regime making it far superior to opposition forces. After the fall of Aleppo two years ago, the opposition appears on the verge of losing another important area, Eastern Ghouta—a highly strategic area due to its proximity to the heart of the capital city, Damascus.

The Ghouta area, housing roughly 400,000 civilians, suffers from intense bombardment by Russian and Syrian warplanes. These attacks coincide with a complete siege of the Ghouta region ongoing for the past several years, and recently resulting in a massacre witnessed by the world through pictures and video recordings. The UN Security Council adopted Resolution 2401, which called on all parties to cease military action for at least thirty days in Syria, lift the siege imposed by the regime forces on Eastern Ghouta and other populated areas, and deliver humanitarian assistance to those affected. So far, the resolution has not yet been implemented.

The Syrian president, Bashar al-Assad, said in a press statement quoted by the official Syrian news agency, SANA, that the resolution came about to help what he described as “terrorists” and said, “Syria is subjected to an information and political campaign aimed at provoking terrorism, which has recently suffered successive blows.” He stressed that the operations carried out by his forces alongside the Russian forces will continue, pointing out that this operation runs in parallel with the opening of humanitarian corridors for civilians to flee. The Syrian opposition considers Assad’s response a means to “encroach on the Security Council resolution and aims to carry out forced displacement and demographic changes, as has happened in other regions.”

The Syrian researcher and published author of the book The Shiite Baath in Syria, written in Arabic, Abdel Rahman al-Hajj, said that Russia’s relationship with Iran and their common interests extend beyond Syria. He considers their partnership in Syria as “one of the most significant partnerships between the two.” Iranian researcher specializing in the Syrian issue, Arash Aziz, similarly remarked that the relationship between Moscow and Tehran is at in peak in recent history and that they share common interests.

Despite this significant partnership, recent military operations against Ghouta reveal some discrepancies. Al-Haj pointed out that Russia wants to portray itself as a major player in international politics with regard to Syria, while Iran seeks to make it a subsidiary of its own, tied to its axis of resistance. He notes how Iran wants to use Syria as a platform through which to influence the heart of the Middle East, but said, “These minor differences are quickly overridden in favor of the intersection of their larger interests.”

The history of the relationship has largely been tense until recently. Tehran was an ally of the West and the United States against Moscow during the Cold War. The latter also refused to welcome Khomeini’s accession to power after the success of the Islamic Revolution, for fear of its religious bent. Former Russian President Dmitri Medvedev even rejected providing Iran with an S-300 missile system in 2008. But recent years have made both sides more interdependent, especially in the face of US and European sanctions to which both have been subjected.

This dynamic raises an important question: Why is Moscow leading the battle in Ghouta and not Iran, which places that region among its priorities? A member of the Syrian National Alliance opposition, Riad al-Hassan, said that Eastern Ghouta constitutes the strategic depth of Iran’s influence in the region. “This requires more careful Iranian calculations before taking any decision to participate in the current operations alongside the regime and Russia, particularly in light of US and Israeli escalation against it,” he said.

A researcher at the Omran Center for Strategic Studies, Sasha El Alu, said that there is “confusion over Tehran’s position on the Eastern Ghouta clashes.” He referred to two main reasons behind this course of events. First, Russian desire to distance Iran from the vicinity of Damascus in order to prevent the expansion of Iranian militias that could fill any potential strategic vacuum in the region. El Alu considers the move “a response from Moscow to Israeli pressure.” Second, Iran perceives Moscow’s behavior as isolationist because Russia refrained from sending large forces into Syria; potentially as a message to Iran that any ground effort would succeed only in coordination with Russia.

The past few weeks in Eastern Ghouta saw unprecedented military escalation between Israel on the one hand, versus Iran and the Syrian regime on the other. The result of the escalation came in the form of Israeli bombing of military bases inside Syria, in retaliation for the downing of its F-16.

There is a general belief among international stakeholders in Syria that the Russian military presence in Syria is reliable and can be trusted. This is in contrast to the Iranian presence, which includes Shia militias, that has increased sectarian tensions in the region. The current US administration considers Tehran the reason for current problems in the Middle East. At the end of 2017, the US administration prioritized confrontation with Iran in the region; announced by former US Secretary of State, Rex Tillerson, at Harvard University. Moscow, which is now breaking away from Tehran, seeks to cooperate with the international community—particularly the United States and the European Union—to maintain their gains in Syria.

Riaz al-Hassan, the adviser to the delegation of the Syrian opposition in the Geneva negotiations, said that the Russia-Iran competition stems from the political dispute and the conflicting agendas of both parties. He added that Moscow has shifted to dealing seriously with the political process instead of military operations, after the fall of Aleppo, to preserve state institutions and prevent the collapse of the army and security services. Tehran, on the other hand, wants the collapse of the Syrian army in order to make broad demographic changes to the country—similar to what it did in Iraq and Lebanon—to spread the Shia doctrine throughout its proxies such as the Iraqi Popular Mobilization Forces and the Lebanese Hezbollah.

During the negotiations in Geneva, the delegation for the Syrian opposition “has seen this discrepancy in the agendas of the parties. We found Russia to be seriously interested in the political process as it tried to break the deadlock through the Sochi Conference and form a constitutional committee. This was central to Resolution 2254,” Al-Hassan clarified. He pointed out that this was met with “repeated sabotage attempts by Tehran,” a phenomenon Moscow has encountered on many issues in the Syrian arena.

According to activist Abu Omar, a resident of Eastern Ghouta, the fighting is aimed at dividing Ghouta into three areas: the Douma area, the central sector, and the Basatin area. He added that this would lead to the same fate that Aleppo faced two years ago, when Russia then sent military police units to prevent the entry of Iranian militia into the city.

Ghaith al-Ahmad works as a journalist for The New Arab. He previously worked as a media coordinator for the Syrian Red Crescent in Deir Ezzor.

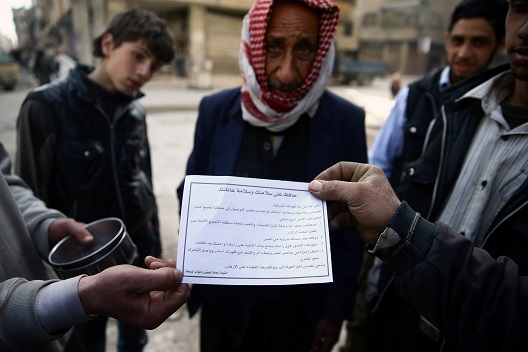

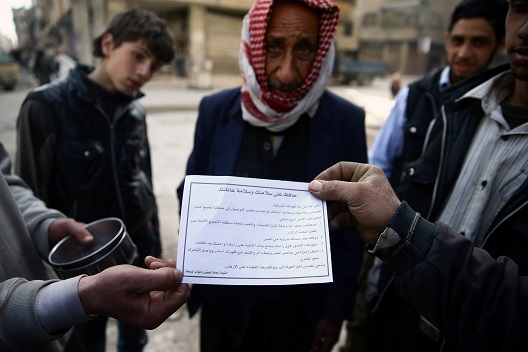

Image: Photo: People hold a warning leaflet dropped by plane entitled "Keep yourself and your family aware" in the besieged town of Douma, Eastern Ghouta,in Damascus, Syria March 11, 2018. REUTERS/ Bassam Khabieh