Among Tehran’s Shia proxies participating in the Syrian civil war in defense of the Assad regime, the Pakistani Zeinabiyoun Brigade remains the most understudied. This may in part be due to the militia’s small size and limited contribution to the war, and because of the militia’s attempt to remain invisible to the prying eyes of Pakistani Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI).

Among Tehran’s Shia proxies participating in the Syrian civil war in defense of the Assad regime, the Pakistani Zeinabiyoun Brigade remains the most understudied. This may in part be due to the militia’s small size and limited contribution to the war, and because of the militia’s attempt to remain invisible to the prying eyes of Pakistani Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI).

A systematic survey of information available in Persian language source material however, not only provides some insights into the history, leadership, composition, and performance of the Zeinabiyoun, but also explains the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps’s (IRGC) strategic objectives with establishing it.

Most of the open source information about the Zeinabiyoun originates from eight short articles in the July 23, 2016 issue of Panjereh, a monthly publication close to the IRGC. The articles appear to be provoked by the Islamic Republic Immigration authorities’ harsh treatment of Shia Pakistani volunteers for the war effort in Syria transiting Iran. The details are not known, but most probably, Iranian immigration authorities had rounded up Shia Pakistanis who—with the IRGC’s assistance—had illegally entered Iran en route to Syria.

In the most important article, a certain Abbas, who is presented as “one of those in charge of the Zeinabiyoun,” and may well be identical with Seyed Abbas Mousavi, the brigade’s chief commander, claims he and other Shia Pakistani activists were in touch with the IRGC Quds Force “for almost 15 years,” prior to establishing the Zeinabiyoun Brigade. In other words, contacts between “Abbas” and the IRGC were established in 2001, at the time of United States led invasion of Afghanistan and the collapse of the Taliban. This claim may be true of “Abbas,” but organic ties between Iranian government agencies, the Shia clergy in Iran, and the Shia Pakistani, predate the 1979 revolution and were never severed.

In the article, Abbas mentions radical-Sunni harassment of the Shia in Parachinar as the main driver behind his political awakening. As the political protests in Syria degenerated into sectarian strife targeting Shia shrines in Damascus, Abbas saw Syria as an “apocalyptic battle ground” for which he felt ready. He claims to have reached out to Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, and obtained a verbal “positive response” to participate in the war in Syria, after which he began to recruit Shia Pakistanis. This recruitment effort, he says, coincidentally happened when the UAE expelled “12,000 Shia,” some of whom moved to Iran and some of whom were Pakistani.

According to Abbas, the IRGC only enrolled 50 Shia Pakistani nationals in its military training program. One of those, also interviewed by Panjereh, who was later promoted to officer and goes by the nom de guerre Karbala, seems to have been among those expelled from the UAE late in 2014 or early 2015. Karbala says he is a native of Parachinar, the capital of the Kurram Agency and the largest city in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas of Pakistan. Karbala says he became politically active because of the Shia-Sunni tensions in Pakistan. When the Zeinabiyoun Brigade was established in Mashhad in 2015, Razavi Khorasan province, Karbala rushed to Iran to join the militia.

Apart from volunteers from Pakistan, and Shia Pakistanis expelled from UAE, there are also some Shia Pakistani theological students from the Jameat al-Mostafa University in Qom who volunteered for the war in Syria.

This author’s survey of funeral services held in Iran for Shia Pakistani nationals killed in combat in Iraq and Syria generally corroborates the information provided in Panjereh.

The Zeinabiyoun Brigade has suffered a total 140 combat fatalities, per publicly accessible documents, though the actual number is likely slightly higher. The first three Zeinabiyoun fighters were killed in combat in Iraq in June and November 2014, the remainder (137) were killed in Syria. This indicates that the IRGC initially incorporated the Pakistanis into Iraqi militias before shifting tactics and deploying them to Syria. Interestingly, there is no sign of Iran using Afghani militants in Iraq.

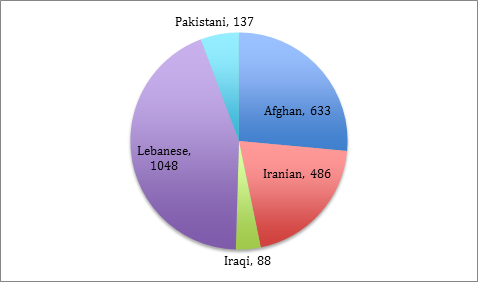

The relatively low number of Zeinabiyoun combat fatalities in Syria is also an indicator of the relatively small size of the militia in comparison with other Shia militias, including the Iraqis, the latter for which there is no reliable statistical information. (Figure 1)

Figure 1: Shia combat fatalities in Syria and nationality January 1, 2012 – April 25, 2017

The first Shia Pakistanis killed in combat in Syria lost their lives in November 2014, which corroborates Karbala’s account of the approximate time of establishment of the Zeinabiyoun. The presence of at least four theological students among the combat fatalities supports claims of Jameat al-Mostafa students and graduates participating in combat.

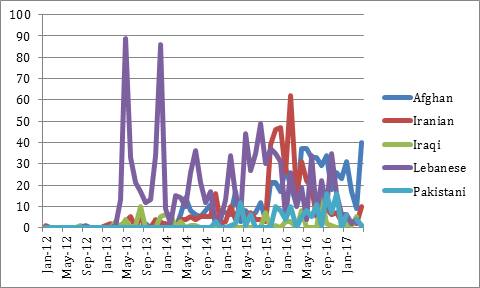

In one respect however, there is a mismatch between claims of the Zeinabiyoun commanders and the data: While the Zeinabiyoun commanders insist their brigade operates independently, the fatalities of the militia follow the same pattern as IRGC losses in Syria. This indicates they operate alongside with and most likely under IRGC command. (Figure 2)

Figure 2: Shia combat fatalities in Syria by nationality and month of death January 1, 2012 – April 25, 2017

Iran walks a fine line when organizing this militia. While Tehran tries hard to improve relations with its nuclear armed eastern neighbor, the IRGC leadership is clearly tempted to recruit Shia Pakistanis fleeing religious intolerance in their home country. These fighters are highly motivated, volunteering for a war in which they, at least theoretically, have the chance of getting even with opponents whom they consider their ‘tormentors’—the mainly-Sunni opposition to the Assad regime and its international backers.

Additionally, the IRGC’s mobilization, training, and deployment of the Shia Pakistanis may not provide an effective deterrence against Pakistan, but it might warn Islamabad to not provide logistical support and safe haven for Sunni Iranian radicals who operate in the Iran-Pakistan border areas. At this point, the IRGC’s effort however, is too limited to make a meaningful impact on Islamabad, but it signals that Iran could scale up if it felt threatened by Pakistan.

Ali Alfoneh is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council.

Image: Photo: A police vehicle patrols near the portraits of (L-R) Pakistan's President Mamnoon Hussain, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani and Pakistan's Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, displayed along a road during Rouhani's visit to Islamabad, Pakistan, March 25, 2016. REUTERS/Faisal Mahmood