Since September 2017, the agreed upon “de-escalation deal” seemed to mark the final chapter of the Syrian civil war; entering into its eighth year. The goal of the Astana talks in 2017 was to sustain the de-escalation deal, in order to minimize violence, secure more aid, and consequently make it “safe” for Syrian refugees to return.

Since September 2017, the agreed upon “de-escalation deal” seemed to mark the final chapter of the Syrian civil war; entering into its eighth year. The goal of the Astana talks in 2017 was to sustain the de-escalation deal, in order to minimize violence, secure more aid, and consequently make it “safe” for Syrian refugees to return.

The gradual recapture of Syrian territories, previously controlled by the Islamic State (ISIS, ISIL, Daesh) and declaration of the defeat of ISIS by the Syrian regime last November, supported the idea of the possible end of the Syrian conflict. Several reports over the past few months discussed “stability returning to Syria” and 2018 as the year that “Syrian refugees return to their homes.”

It might be true that the past year witnessed an increased number of displaced Syrians returning to their homes. In June 2017, the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) reported “significant returns” during the first six months of the year. However, it would be pre-mature to draw significant conclusions based on these developments.

According to the figures released by the International Organization on Migration (IOM), nearly 715,000 Syrians were able to return home between January and October 2017, the majority displaced within the borders of Syria. According to the same data by IOM, more than 37,000 of those returnees were forced into displacement again. On the other hand, during the same period of time, an additional 1,452,636 individuals were newly displaced inside Syria, most of them were from Raqqa and Deir Ezzor governorates; where battles against ISIS were taking place. This brought the total number of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) in Syria to around 6.1 million since 2011. Comparing the figures of returnees to the total number of IDPs provides an insight on why it would be misleading to talk about a trend of “Syrians returning to their homes.” According to a new report released jointly by six humanitarian organizations earlier this month, for every internally displaced Syrian who was able to return home last year, three new persons were pushed into displaced, because of escalating violence.

The IOM figure includes 66,000 refugees who returned to Syria from their displacement in neighboring countries. This figure might seem significant on its own however, putting it in context is important to understand what this figure might reflect:

First, compared to the total figure of Syrian refugees in neighboring countries; around five million, and to those in Europe; around one million, the figure of those returning to Syria is quite small, and cannot be used to refer to a trend of Syrians returning to their homes.

Second, the past year witnessed a growing closed-door policy in neighboring countries—not including Europe and the United States—in the face of new flows of Syrian refugees trying to escape the on-going war. According to the same joint report, Jordan and Turkey banned 300,000 Syrians from entering and pushed them back to Syria. Since June 2016, the borders between Jordan and Syria remain closed when Jordan declared the area “a closed military zone” for security concerns. Turkey is building a wall along the 911 kilometer (566 miles) border with Syria, and is expected to complete it by this spring.

While borders between Lebanon and Syria officially re-opened, anti-refugee hostility continues to grow. Syrians are subjected to stricter laws that restrict the right to work and the movement of Syrian refugees. Curfews for Syrians are enforced in forty-five municipalities across Lebanon. Lebanese political figures have repeatedly called for deporting Syrian refugees since 2013. One of the most remarkable statements reflecting Lebanon’s willingness to push Syrian refugees back into Syria was made by the Lebanese President, Michel Aoun in his speech before the United Nations General Assembly last September. Noting that the Syrian government is now in control of 85 percent of its territory, Aoun stated that “there is an urgent need to organize the return of (Syrian) refugees to their country.” He considered “the claim that refugees will not be safe if they return to their homeland (as) an unacceptable excuse.” Besides restrictions on Syrian refugees, humanitarians and researchers working with the Syrian refugee community reported increased difficulty in obtaining work permits in Lebanon, in what apparently is aimed to discourage their work.

Third, and most importantly, there is little information available on who the 66,000 Syrian returnees are, and on whether their return was voluntary. There are reasons to believe that some element of involuntary return was involved. In September 2017, Human Rights Watch reported that Syrian refugees in Arsal, a border town in northeast Lebanon, were facing pressure to return to Syria, because of the harsh conditions in the town, where 60,000 Syrian refugees resided, and where confrontations took place between the Lebanese Army and ISIS fighters.

Also, another source of pressure to return could be the inability of family members to leave Syria and reunite with their families in the host country. According to UNHCR, around 8,000 Syrian refugees returned from Jordan to Syria in 2017. When asked about the main reason for leaving Jordan, the vast majority of them mentioned family reunification as the main drive behind their decision to return. Also, the fact that they returned to Syria does not necessarily mean that they were able to return to their homes/ hometowns. Moreover, there has been an increase in deportation cases of Syrian refugees by authorities in Turkey and Jordan for what authorities consider “security concerns.” In some cases, maintaining contact with family members who live in Syria is considered a security concern.

Thus, there is little to no evidence to support the idea that Syrian refugees are exercising their right to return, nor it has become safe for them to return to Syria. During the first year of the Syrian conflict, all involved parties; the refugees themselves, the hosting countries as well as the international community regarded the waves of exodus from Syria as temporary; as “a matter of time” before the displaced would return. With the prolonged and escalating conflict, the displacement is no longer temporary. It seems stakeholders in the conflict are arriving to a similar pre-mature conclusion about the end of the war in Syria as being “a matter of time.”

With the recent failure of the Russian-sponsored negotiations at Sochi, and the rapid escalation in violence on the ground over the past few days, what should be expected is not an end of the war, but rather a de-facto collapse of the de-escalation deal, which will likely result in more Syrians forced into displacement. A viable scenario of voluntary, safe, and a sustainable return for millions of Syrian refugees does not exist. Pushing Syrian refugees into a forced-return to a country torn by civil war, where they face the danger of continuing violence, and the high potential of retaliation by the Assad regime, is wrong. There is a need to think of the Syrian refugee crisis in terms of the reality of the situation on the ground, rather than the wishful thinking of stretched host-countries, which are increasingly over-burdened by the millions of refugees.

Hanan Elbadawi is an independent writer and analyst, experienced in humanitarian issues and Arab affairs. Most recently she worked as the founding manager of the Program on Refugees, Forced Displacement and Humanitarian Responses at Yale University. Previously, she worked with the League of Arab States, the International Peace Institute and the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights. Hanan holds a Master of Advanced Study in Global Affairs from Yale University, and an M.A. in international relations from the American University in Cairo.

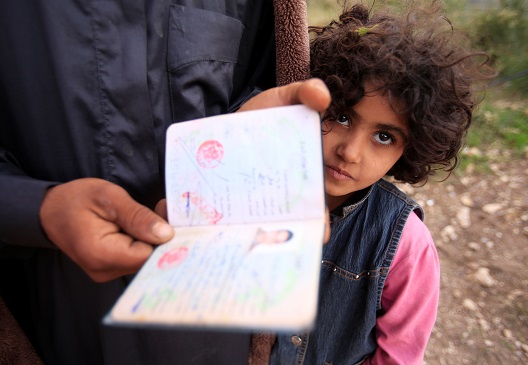

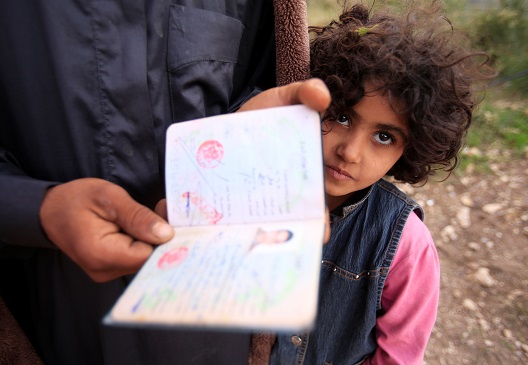

Image: Photo: A Syrian refugee man holds a document in Ain Baal village, near Tyre in southern Lebanon, November 27, 2017. Picture taken November 27, 2017. REUTERS/Ali Hashisho