Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto visited Turkey last week, on April 9, not long after he welcomed Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in Jakarta this February as part of Erdoğan’s tour of Asia. The exchange of visits is only one sign that relations between the two countries are strong—and growing.

But there’s a bigger picture to the exchange as well: Ankara’s approach to its relationship with Jakarta is demonstrative of its overall strategy toward the members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Such a strategy is portrayed in Ankara’s Asia Anew Initiative, launched in 2019, which prioritizes economic engagement with Asian countries.

The last time Prabowo visited Turkey—in July 2024, then the president-elect and minister of defense—he underscored Turkey’s significance as a strategic partner for Indonesia. There, Prabowo and Erdoğan also reportedly discussed the possibility of expanding the Indonesia-Turkey partnership, including in the defense sector.

The countries have a history of defense collaboration: For example, they signed an industry cooperation agreement in 2010. Indonesian state-owned firm PT Pindad and Turkish armored-vehicle manufacturer FNSS worked together in the 2010s to produce a medium-weight tank, the Kaplan MT. The two countries have also intensified their collaborative efforts in intelligence and combating terrorism. In 2023, Indonesia bought twelve reconnaissance drones, worth $300 million, from Turkey.

Considering Turkey’s military might—it has the second largest military force in NATO—it makes sense that Prabowo (a former defense minister and a retired army general) and a number of Indonesian stakeholders are continuing to prioritize defense cooperation with Turkey. This is demonstrated by a drone agreement that the countries signed this February, which will see Turkish company Baykar export sixty Bayraktar TB3 and nine Bayraktar Akıncı drones to Indonesia. Baykar also agreed to a joint venture with Republikorp, an Indonesian defense company, to construct a drone factory in Indonesia.

The countries have collaborated in other ways. In 2021, Dirgantara Indonesia (a company that makes military and civilian aircraft) signed a memorandum of understanding with Turkish Aerospace to cooperate on the production of the N219 aircraft and the modernization of the Turkish CN235 aircraft fleet.

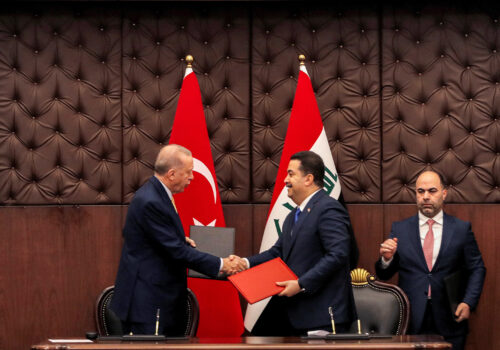

Trade between the two nations in 2024 amounted to $2.4 billion, representing an increase of over 12 percent from the previous year. In addition, Indonesia and Turkey have been working since 2017 on the Indonesian-Turkish Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement. At Erdoğan’s meeting with Prabowo this February, the two leaders reportedly agreed to work on finalizing the agreement and thus widen the market for products produced in each country. They also signed thirteen agreements in the fields of energy, health, agriculture, defense, communication, and education.

In addition, as Indonesia prepares to move its capital city from Jakarta to Nusantara—located in East Kalimantan—Erdoğan said during his February trip that he would like Turkish construction companies to take part in building the new capital. Erdoğan and Prabowo also emphasized, during the visit, that the two-state solution is the most viable approach to achieving peace in Gaza, and Erdoğan said he intends to work with Indonesia on the reconstruction of Gaza.

In the education sector, the Turkish government has offered a scholarship program for Indonesian students to study in Turkey; the number of students enrolled has increased from 2,500 in 2019 to 4,662 as of 2023. These students are offered a one-year Turkish language course in preparation, which represents one facet of Ankara’s soft power.

All of this highlights how the Indonesia-Turkey bilateral relationship has developed over time and across multiple sectors and issues. These two countries’ collaboration is in alignment with Turkey’s Asia Anew Initiative and also with Indonesia’s goals to engage in free and active foreign policy—and to avoid excessive dependence on any major powers.

In addition, Turkey has pursued a more active relationship with ASEAN members as Asia has accounted for more and more of the global economy and as the region has become the epicenter of global trade. ASEAN countries produced 7.2 percent of the global gross domestic product in 2024, and they boast a combined population of 692 million.

In order to revitalize Turkey’s economy by diversifying its trade, it is foreseeable that Ankara will seek to strengthen its economic relationship with ASEAN members, including Indonesia. Ankara has signed free trade agreements with ASEAN members Malaysia (in 2015) and Singapore (in 2017), and it is currently in negotiations with Indonesia and Thailand as part of its broader strategy to enhance cooperation with countries in the region. Additionally, it is likely that Turkish companies will increase their investments and involvement in infrastructure initiatives throughout the ASEAN region in light of ongoing infrastructure needs across Southeast Asia.

The Turkey-ASEAN relationship also stretches across sectors and issues, touching everything from the economy to education. For example, in 2023, Turkey and ASEAN offered a joint scholarship to students in ASEAN countries enabling them to attend master’s-degree and Turkish-language programs.

As for what lies ahead: Turkey and ASEAN countries will likely continue to strengthen their people-to-people connections as a result of Turkey’s Asia Anew Initiative. As ASEAN member states look to avoid becoming overly dependent on any major powers, they are likely to expand cooperation with middle-power countries, such as Turkey.

But don’t expect this to result in Turkey turning entirely eastward, abandoning the West. In a 2024 speech, Erdoğan contended that Turkey’s various geographical, human, economic, and historical connections globally render it incapable of being contained within a bloc. In addition, countries on the outskirts of the Turkey-ASEAN relationship—including the United States and China—will play a role in shaping the future of these ties, as such larger powers impact how Turkey and ASEAN members manage their economic interests and navigate the geopolitical landscape.

Nevertheless, Turkey and ASEAN countries can deepen their mutually beneficial partnership in a way that assists the former in overcoming its economic challenges and unlocks new markets and opportunities for ASEAN members.

Adinda Khaerani Epstein is a former political communication researcher at the Istanbul-based research institute Turkish-Asian Center for Strategic Studies. She is also a specialist on Southeast Asia and US-Turkey relations at Geopolitical Intelligence Services and an adjunct fellow at the Gold Institute for International Strategy.

The views expressed in TURKEYSource are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Atlantic Council, its staff, or its supporters.

Further reading

Thu, May 2, 2024

A fair wind over Mesopotamia, or just hot air?

TURKEYSource By Rich Outzen

The first trip to Iraq in a decade by Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan could lead to significant cooperation for the stability of the region.

Fri, Jan 24, 2025

There’s a path forward for Turkey-Greece cooperation—but it requires a dose of realism

TURKEYSource By Harry Tzimitras

For a successful Turkey-Greece partnership, both sides need to actively seize the opportunities of cooperation.

Fri, Dec 6, 2024

What the US-Turkey relationship will look like during Trump 2.0

TURKEYSource By Rich Outzen

The second Trump term presents new opportunities and risks for US-Turkey relations.

Image: Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto speaks during a press conference with Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan (not pictured), at the Presidential Palace in Bogor, Indonesia, February 12, 2025. REUTERS/Ajeng Dinar Ulfiana REFILE - QUALITY REPEAT