For more than five years, Russia has used its military and proxy forces to wage a low-intensity but still very real war in eastern Ukraine. Newly-elected Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy would like to end that conflict. On October 1, he announced an agreement based on the “Steinmeier Formula” to advance a settlement.

Angry crowds took to the streets of Kyiv and other Ukrainian cities over the weekend to denounce the agreement, equating it with capitulation to Moscow. But is it? At this point, not enough is known about details of the agreement—or even if the agreement will hold—to reach a judgment.

Shortly after the Russian military seized Crimea and Russia illegally annexed the peninsula in March 2014, fighting broke out in eastern Ukraine. So-called “separatist forces,” with Moscow-provided leadership, funding, ammunition, heavy weapons, and sometimes regular units of the Russian army, occupied part of the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts, also called the Donbas.

Five-plus years of fighting have claimed over 13,000 lives and caused some two million people to flee. Agreements reached in Minsk in September 2014 and February 2015—the latter with the direct participation of the German and French leaders—have not been implemented.

In 2016, then German Foreign Minister (and current German President) Frank-Walter Steinmeier proposed to resolve some sequencing questions from Minsk disputed by Russia and Ukraine. He suggested that local elections be held in the part of the Donbas currently occupied by Russian and Russian proxy forces according to Ukrainian law and supervised by the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). Once the OSCE certified the elections as free and fair, the occupied areas would gain special status, and Ukrainian sovereignty would be restored over all of the Donbas, including along the Ukraine-Russia border.

The October 1 settlement announced by Zelenskyy referred specifically to the Steinmeier Formula. Many in Ukraine worry that the Steinmeier Formula aims at promoting peace—but not necessarily a just peace for Ukraine—so Germany and other European states can get back to business as usual with Moscow.

Zelenskyy, however, announced a seemingly modified version of the Steinmeier Formula. He stated that local elections in the occupied region would be held only after Russian and Russian proxy forces withdrew and Ukraine reestablished control over the border with Russia. This sequencing would amount to a victory for Kyiv and, if accepted by Moscow, would constitute a significant departure from Russia’s previous position. Of course, if the Kremlin does not accept this sequencing, the October 1 agreement is doomed.

Those who call the agreement a surrender fear that local elections, if not managed carefully, will give political power to allies of those who have run the so-called Donetsk and Luhansk “People’s Republics.” By all credible accounts, the “People’s Republic” authorities have done a horrible job managing local institutions and delivering government services. In elections held under Ukrainian law, monitored by the OSCE to ensure that it met free and fair standards, and with the bad guys with guns having left for Russia, would voters really choose to empower people with demonstrably bad track records at governance?

Another issue that provokes demonstrators’ concern is the question of special self-governing status for the occupied territories. At this point, however, the debate is taking place in a vacuum, because the meaning of “special self-governing status” has yet to be clarified. Zelenskyy said that the Rada would develop a new law on local self governance and that it would protect Ukraine’s key interests.

Some oppose special status on principle, but it likely would prove impossible to settle the conflict without something that looks “special” for the Donbas. The appropriate question is how much autonomy does Kyiv cede to local authorities?

Stay updated

As the world watches the Russian invasion of Ukraine unfold, UkraineAlert delivers the best Atlantic Council expert insight and analysis on Ukraine twice a week directly to your inbox.

Certain government powers—such as the responsibility to set foreign, defense and security, macro-economic and macro-financial policies, to name a few—should remain in Kyiv. That is vital for Ukraine’s coherent functioning as a national state. But other powers touching on questions related to education, health, and local police might be transferred to local authorities without comprising Ukraine’s national unity.

According to Zelenskyy, the Rada will develop the specific legislation that sets out what authorities can be passed down to the Donbas. That question also may well prove problematic with Russia, which could mean collapse of the October 1 agreement.

The 2003 Kozak memorandum provides a likely example of what the Kremlin envisages for special self-governing status for the Donbas. Kozak’s memorandum spelled out terms for reintegrating the breakaway region of Transnistria into Moldova. In the end, the Moldovan government rejected the memorandum, because it would have given regional authorities in Transnistria the ability to veto national-level decisions, such as foreign policy and Moldova’s relationship with the European Union, and made national policy-making unworkable.

Ukraine should not accept anything like the Kozak memorandum. To do so would severely complicate national policy-making and amount to abandoning Kyiv’s long-proclaimed course of drawing closer to Europe and its institutions.

Eurasia Center events

The main point, however, remains: we do not know what the terms of special self-governing status are, just as we do not know whether Moscow would accept local elections in the Donbas only after it pulled out its forces and Ukraine had reestablished control. Depending on how these questions are answered, the October 1 agreement could be good for Kyiv, or it could bad.

Before pronouncing a verdict, having answers to these questions would appear wise.

Steven Pifer is a William Perry research fellow at Stanford, a nonresident senior fellow with Brookings, and a former US ambassador to Ukraine. He tweets @steven_pifer.

Further reading

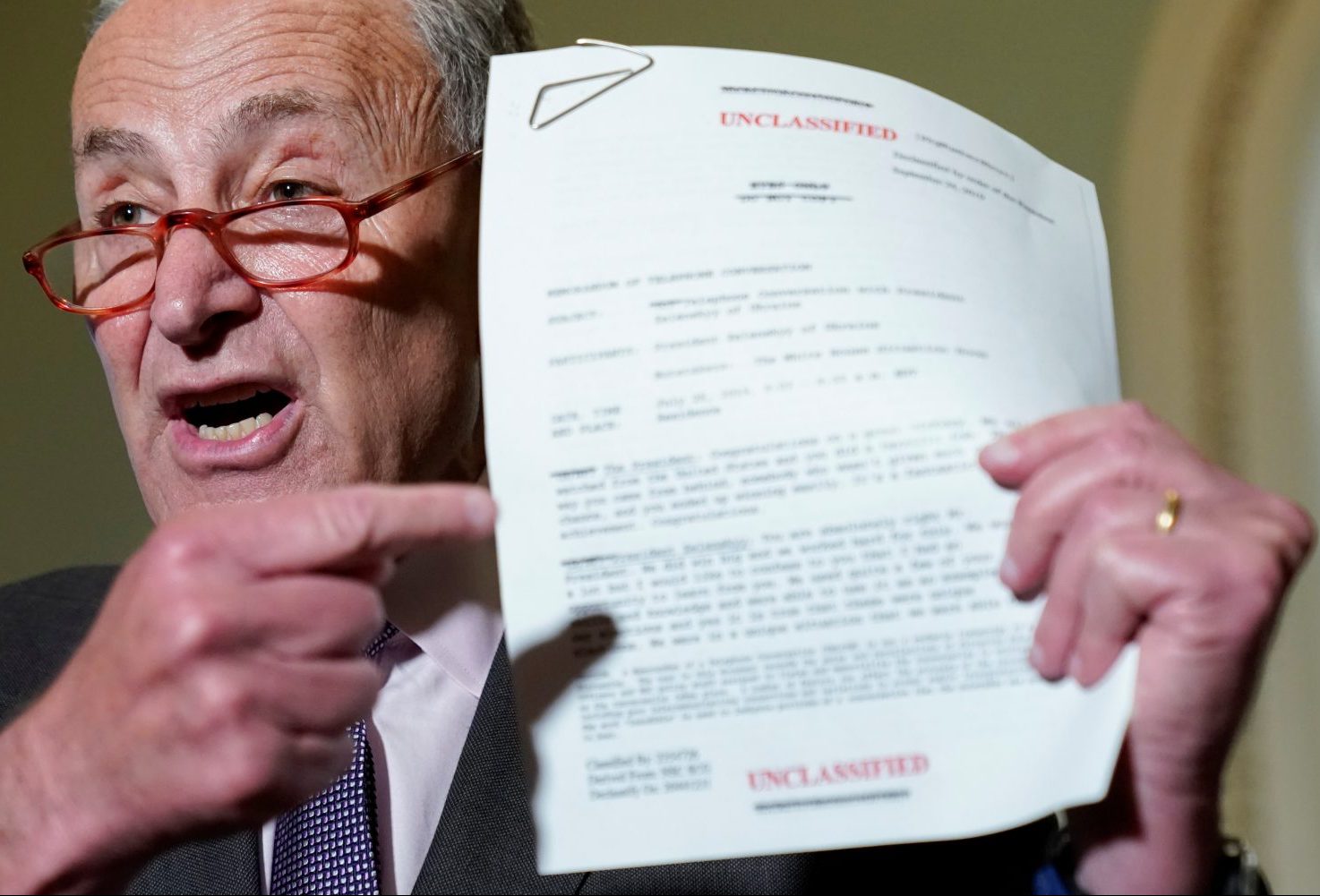

Image: People attend a rally against the approval of the so-called Steinmeier Formula, in Kyiv, Ukraine October 6, 2019. REUTERS/Valentyn Ogirenko