The latest big news from Kyiv as of October 1 is that President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has confirmed that he and his team have accepted the “Steinmeier Formula” as the basis for moving the Normandy Four leaders out of their impasse and toward peace in Ukraine.

At a hastily convened press conference late in the day, he made the announcement but also gave assurances that this does not spell capitulation before Moscow. Ukraine has been under growing pressure to accept this compromise plan, with France’s President Emmanuel Macron continuing to take the lead in promoting this German diplomatic initiative from 2016 that Ukraine has been wary of.

After Zelenskyy’s announcement, angry protestors from former President Petro Poroshenko’s camp and others demonstrated in front of the presidential building.

But all sides want to be seen to be moving forward and breaking the deadlock. Hence, Russia, France, Germany, and more reluctantly Ukraine, seem to be prepared finally to give it a try.

Stay updated

As the world watches the Russian invasion of Ukraine unfold, UkraineAlert delivers the best Atlantic Council expert insight and analysis on Ukraine twice a week directly to your inbox.

Without going into details, as this formula has already been amply discussed, I would like to offer some questions for Zelenskyy and his team to consider, as a former UN diplomat and someone who previously served for almost 20 years with UNHCR.

In applying the Steinmeier Formula, the key question is the sequence. The order in which things will take place is the main source of divergence between the Ukrainian and the Russian sides. The order of things has to be clarified and agreed upon.

Security has to come first, which means not only the withdrawal of troops but the disarming of armed formations. But who will oversee this?

At what stage will Ukraine recover control of the Russian-Ukrainian border? Sooner, rather than later? This is important.

For democratic, read fair and representative, elections to be held it is not enough simply to insist that they be held under Ukrainian law and be endorsed by the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. What about the 1.6 million IDPs, effectively forced out from the occupied areas and who fled westward seeking the protection of the Ukrainian state? And those who chose to flee the conflict to Russia and Belarus? Will all of them have an opportunity to vote—even as absentee voters? If not, can the residual population be accepted as fully representative of the wishes and allegiances of the occupied area? Is Ukraine, and the outside world, prepared to accept the verdict through the ballot box of a pro-Russian element and the Moscow-appointed leaders as a democratic plebiscite?

All sides are conspicuously silent about the tricky question of an amnesty for those who have promoted Russia’s cause in the occupied area, whether by arms or other anti-Ukrainian activity. Clearly, Ukraine does not want to pardon such people, let alone allow them into the Ukrainian body politic as “representatives” of the Donbas.

And, of course, the issue of limited self-government for the “separatist” areas so insisted on by Moscow. On what terms and for how long? Ukraine has already made it clear under the present and previous administrations that it will not agree to federalize Ukraine, or grant something resembling autonomy for the areas in question, especially with the right to veto Kyiv’s westward leaning foreign and security goals.

Eurasia Center events

How does all this connect with undoing Russia’s annexation of Crimea, altering Putin’s attitude toward Ukraine and securing a safer security architecture in Europe and beyond?

Last, but not least if, at the next Normandy Four summit, which both Presidents Macron and Zelenskyy indicate should take place fairly soon, what happens if there is no agreement or breakthrough? Can Zelenskyy, given the political climates in both Washington and London, realistically hope to apply his plan B—namely, invite the United States and British leaders into the Normandy Four process?

Already there is considerable anxiety in Ukraine, even if stirred up for political purposes, that Zelenskyy is caving in to Moscow. Between the pressure on him from Moscow, France, and Germany to compromise, and Washington absorbed in its own political wrangling, is Ukraine about to be sold out and further weakened by internal splits? These are the questions the president and his team should weigh.

Bohdan Nahaylo is a British-Ukrainian journalist and veteran Ukraine watcher based in Kyiv, Ukraine. He was formerly a senior UN official and policy adviser, and director of Radio Liberty’s Ukrainian Service.

Further reading

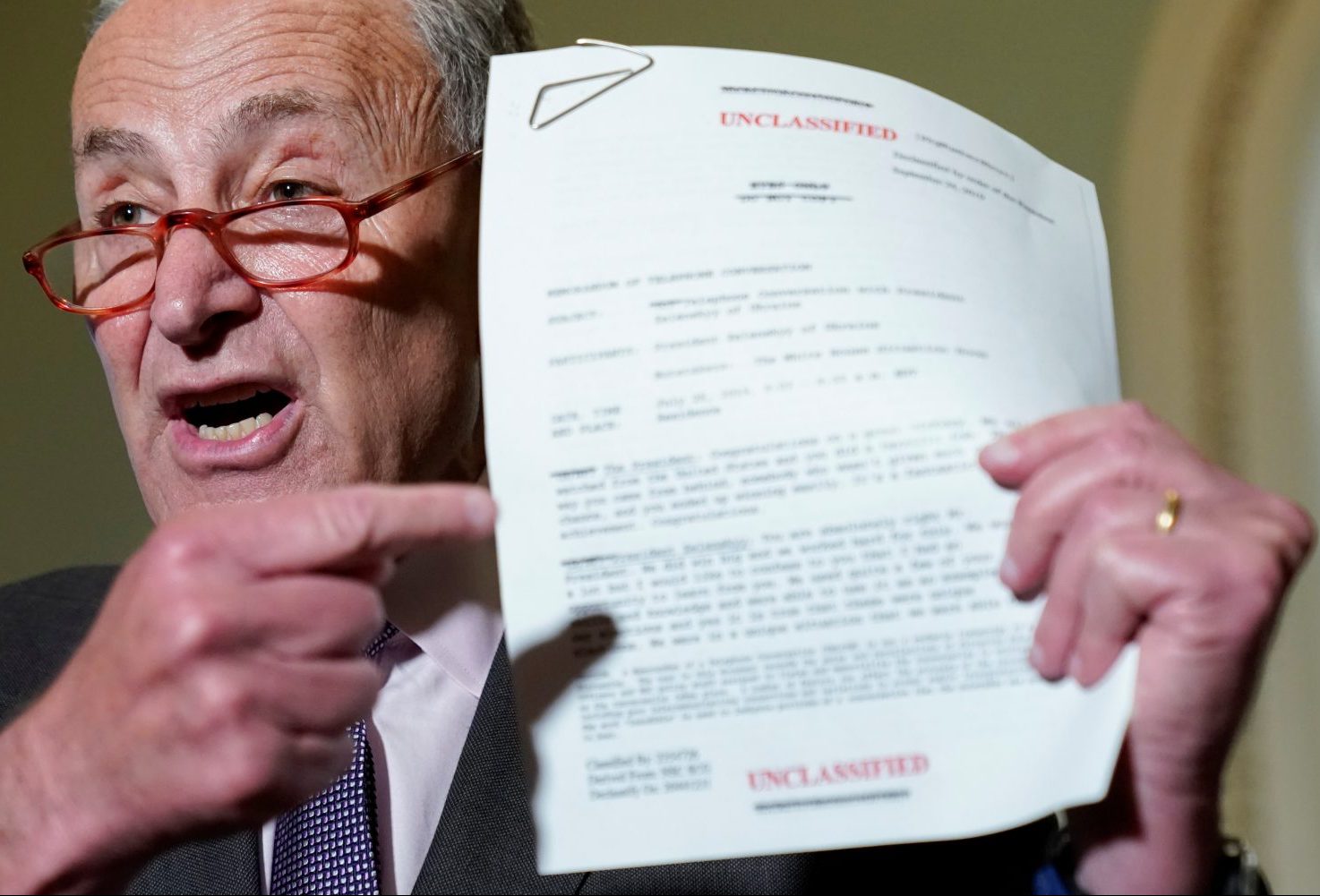

Image: Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy reacts during a news conference in Kyiv, Ukraine October 1, 2019. REUTERS/Valentyn Ogirenko