Ukraine has spent much of autumn 2019 in the international headlines, as a result of the Trump impeachment inquiry and the promise of progress in the Russo-Ukrainian peace process. This spike in media attention has helped revive outside interest in all things Ukrainian, with mixed results. Many journalists have clearly struggled to make sense of Ukraine’s Byzantine political swamp, while others have found the Steinmeier Formula remarkably un-German in its baffling inexactitude, leading to the usual litany of bad takes and outright falsehoods.

At the same time, however, editors from some of the world’s biggest media outlets appear to have decided this was the right moment to update their style guides. A number of global heavyweights have recently adopted the Ukrainian-language derived “Kyiv” as their official spelling for the country’s capital city, replacing the Russian-rooted “Kiev.” This trend began with the Associated Press in late August. Since then, the Wall Street Journal, the Washington Post, the Telegraph, and the BBC have followed suit.

This rush to Ukrainianize spellings is not only a response to Kyiv’s sudden newsworthiness. It represents the latest chapter in a long-running campaign to secure recognition for the Ukrainian-language versions of Ukrainian place names, and is part of a much broader post-Soviet drive to assert an independent Ukrainian identity. These efforts have not always met with success. For example, the Ukrainian authorities first endorsed “Kyiv” as the official English-language spelling back in the mid-1990s, but beyond the rarefied world of diplomatic protocol, most members of the international community paid no attention and continued with the more familiar “Kiev” instead.

This underwhelming response was symptomatic of the ignorance and indifference shaping outside attitudes toward Ukrainian statehood during the first decades of the country’s independence. Indeed, prior to the outbreak of the Russo-Ukrainian War, many people wondered what all the fuss was about and typically dismissed calls to adopt Ukrainian spellings as the ravings of a nationalist fringe. Others saw it as pure presumption on Ukraine’s part. Somewhat unfairly, they asked why there was no similar clamor to rebrand “Moscow” as “Moskva” or “Rome” as “Roma,” ignoring the obvious imperial imposition evident in Ukraine’s case but markedly absent from other Anglicized European place names. A far more meaningful comparison would be the post-colonial name changes in Asia such as the switch from Ceylon to Sri Lanka or the change from Bombay to Mumbai. However, few seemed to regard Ukraine’s own post-imperial sensitivities as worthy of the same consideration.

Stay updated

As the world watches the Russian invasion of Ukraine unfold, UkraineAlert delivers the best Atlantic Council expert insight and analysis on Ukraine twice a week directly to your inbox.

All this changed when Russian President Vladimir Putin invaded Ukraine. It is no coincidence that international attitudes toward the “Kyiv vs. Kiev” debate have undergone a radical transformation since 2014. Like so many other aspects of Ukrainian identity politics, Russia’s attack has electrified the issue, infusing it with entirely new meaning among domestic audiences and encouraging the outside world to think again. With Russian tanks parked in the Donbas and Moscow propagandists denouncing Ukraine as an accident of history, the continued use of Russian-language transliterations for Ukrainian towns and cities became not only absurd but also grotesque.

As a result, the pre-2014 trickle of institutions and media outlets embracing the “Kyiv” spelling became a flood. In addition to the international press, the list of post-2014 converts includes dozens of airlines and airports, numerous academic dictionaries and textbooks, and the hugely influential United States Board of Geographic Names. Ukraine’s #KyivNotKiev campaign will necessarily continue, but we may finally have reached the tipping point. “Kyiv” has now become the standard spelling in much of the English-language world, while those still clinging to “Kiev” risk accusations of outmoded thinking.

Not everyone is cheering this triumph of Ukrainian transliteration. Critics have long dismissed Ukraine’s post-independence name games as a populist sideshow that distracts from the more urgent tasks of fighting corruption and building a functioning economy. Changing the names of the country’s streets, towns, and cities will not put food on the table, they argue. This bread-and-butter approach is understandable in what remains one of Europe’s poorest societies, but it also misses the larger point.

To appreciate the significance of the “Kyiv vs. Kiev” debate, one must first step back and view it in terms of the deep-rooted national identity crisis caused by centuries of Tsarist and Soviet russification. For hundreds of years, successive Russian leaders sought to absorb Ukraine into their country’s national heartlands, exploiting the cultural closeness between the two nations to overwhelm and incorporate the historically Ukrainian lands to the south. Changing political and ideological considerations had little impact on this overarching imperial objective, with tsars and commissars alike regarding the downgrading of Ukrainian identity as a national security priority.

Eurasia Center events

The tools and tactics employed in pursuit of this goal reflected the sheer scale of the undertaking. Generations of Ukrainians found themselves subjected to everything from forced famines and mass deportations to educational apartheid and language bans, with wave after wave of population transfers serving to transform the demographic destiny of the country. Meanwhile, histories were rewritten and inconvenient chronicles destroyed. No single document captures the Russian denial of Ukrainian identity quite as succinctly as the 1863 “Valuev Circular.” A Tsarist decree banning Ukrainian-language publications, it states matter-of-factly, “A separate Ukrainian language has never existed, does not exist, and cannot exist.”

This relentless russification succeeded in robbing Ukraine of an independent identity, both at home and abroad. Responsible for the complex regional nuances of today’s Ukrainian population, it lies behind the country’s enduring international ambiguity. Nor is it consigned to the dustbin of history. Even now, Putin continues to proclaim Russians and Ukrainians as “one people” (i.e. Russians), while his proxies in occupied eastern Ukraine denounce Ukrainians as traitors and call for the entire country to become a Russian protectorate.

Against this backdrop, Ukraine’s desire for the outside world to use Ukrainian-language transliterations appears anything but trivial. On the contrary, it is a plea for symbolic support in what is one of world history’s last great independence struggles. Ukraine’s nation-building journey is far from over, but establishing Ukrainian names for Ukrainian places is an essential early step on the long road to recovery. The international media’s ongoing adoption of the preferred “Kyiv” spelling may seem inconsequential, but it represents a meaningful contribution to this process.

Peter Dickinson is a nonresident fellow at the Atlantic Council and publisher of Business Ukraine and Lviv Today magazines. He tweets @Biz_Ukraine_Mag.

Further reading

The views expressed in UkraineAlert are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Atlantic Council, its staff, or its supporters.

The Eurasia Center’s mission is to enhance transatlantic cooperation in promoting stability, democratic values and prosperity in Eurasia, from Eastern Europe and Turkey in the West to the Caucasus, Russia and Central Asia in the East.

Follow us on social media

and support our work

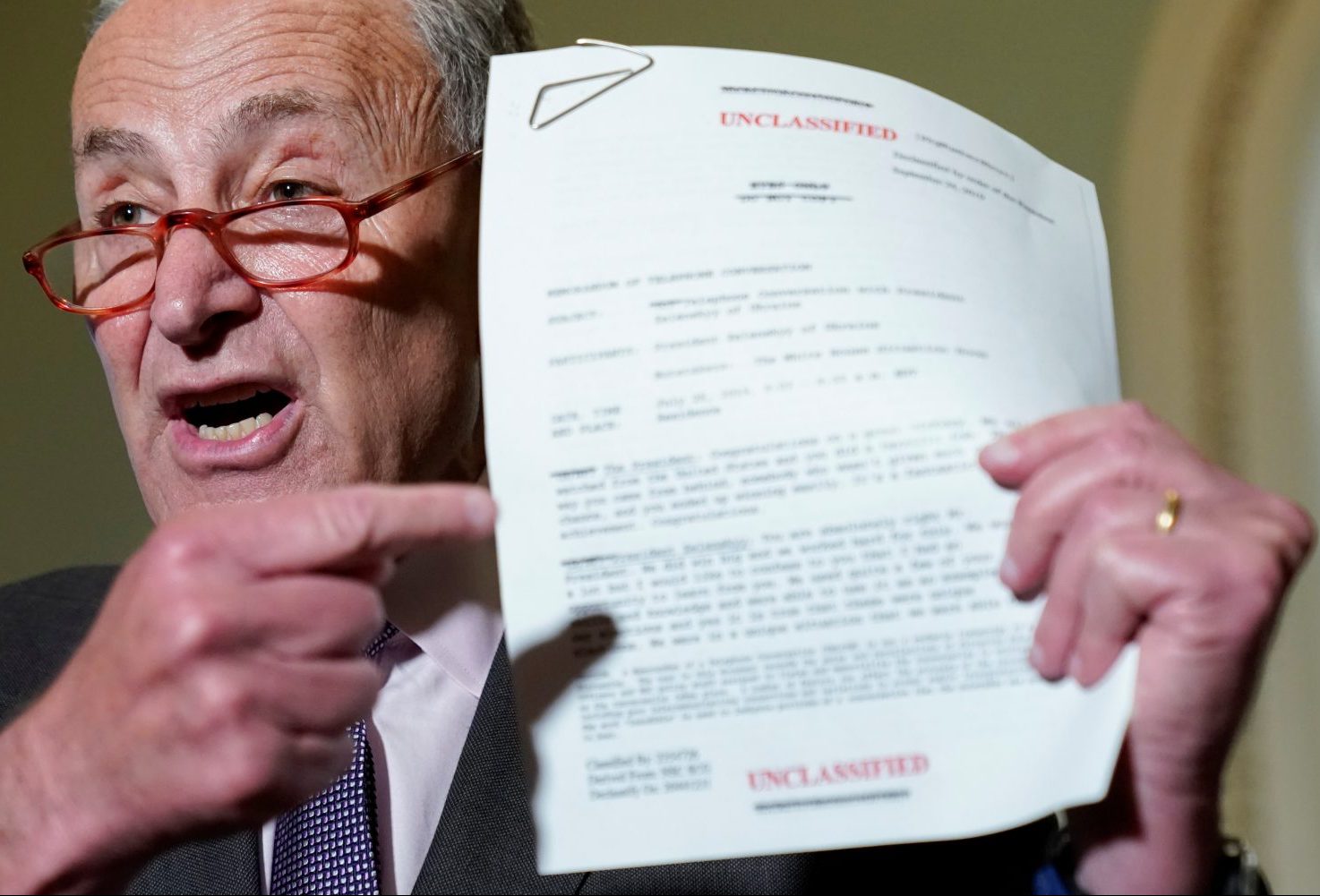

Image: A tote bag by Ukrainian designer Julia Popyk reads Kyiv, the Ukrainian language spelling of the city, that many English-language newspapers have recently embraced. Credit: Melinda Haring