Deportation, exile, annexation, and suppression. It’s the tragic cycle of Crimean Tatar history. But some brave activists are determined to make a difference in the face of such adversity.

Crimea’s indigenous people, the Muslim Crimean Tatars, have faced enormous challenges for generations. They suffered mass deportation by the Soviet regime in 1944 followed by two generations of exile in Central Asia, before returning home to rebuild lives from scratch in an independent Ukraine. More recently, they have endured constant pressure and persecution by Russian occupation authorities for the past seven years since the illegal 2014 annexation of Ukraine’s Crimean peninsula.

As Russia’s occupation authorities tried to separate and isolate human rights activists, the Crimean Tatar community formed Crimean Solidarity, an NGO that fights for the freedom of Crimean political prisoners and provides information not controlled by the Russian Federation.

As many Crimean Tatar men are detained and sentenced to long jail sentences, there is a growing community of Crimean Tatar women breaking stereotypes that Islam treats women as subordinate. In the struggle for survival and freedom, and via organizations like Crimea Solidarity, Crimea Tatar women are increasingly taking on leading roles. The recently released documentary film Crimean Solidarity chronicles their inspirational efforts.

In Russian-occupied Crimea, it is becoming increasingly difficult to live a free life. Those who speak out against the Russian regime or show support for Ukraine are immediately silenced and jailed. Crimean Tatars are not the only ones to be persecuted by the Russians in Crimea. But they represent a staggeringly high percentage of those targeted, compared to their 13% pre-occupation share of the peninsula’s population.

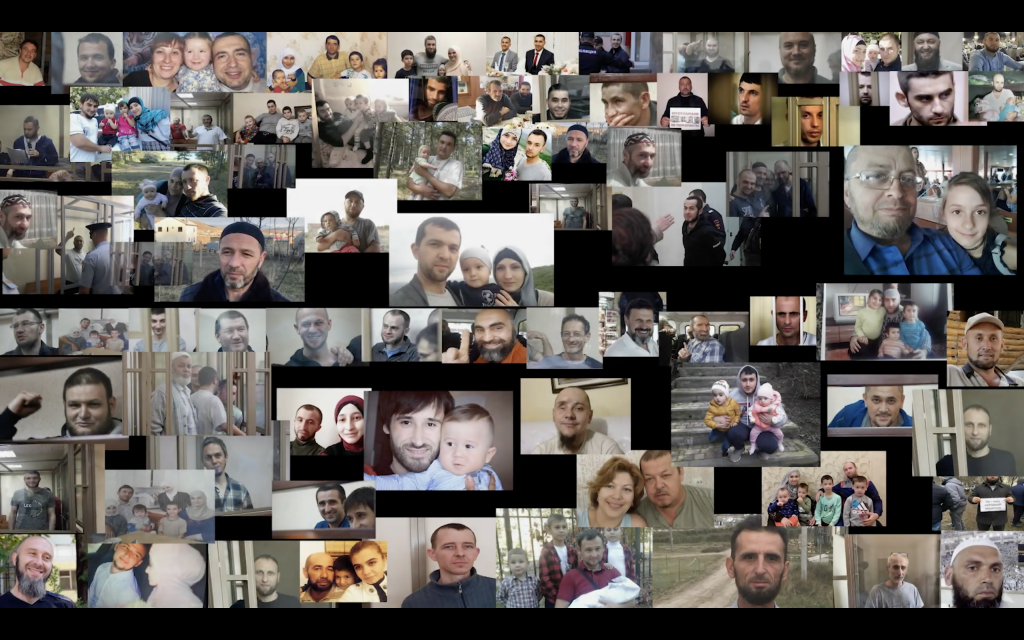

At least once a month, a new activist or group of Crimean Tatars is sentenced to prison. An active religious life can be enough to land you charges of terrorism and sentences of up to 20 years. Once in Russian detention, Crimean Tatar political prisoners face brutal conditions including torture. Over 100 Crimean Tatar men have been detained, leaving their wives to take care of their families.

The wives of political prisoners must assume the roles of both father and mother in raising their children. This means becoming the breadwinners for the family and fighting for justice while facing Islamophobia, sexism, prejudice, and intimidation techniques.

Stay updated

As the world watches the Russian invasion of Ukraine unfold, UkraineAlert delivers the best Atlantic Council expert insight and analysis on Ukraine twice a week directly to your inbox.

Starting in January 2020, the Kyiv Post video team kept in close contact with women activists in the Crimean Tatar community. Lutfiye Zudieva, a human rights activist and civic journalist who has been detained herself, helps the wives of political prisoners to connect with each other. The Kyiv Post also followed the families of human rights activist Emir Ussein Kuku and civic journalist Nariman Memediminov.

The cases of Emir Ussein Kuku and Nariman Memediminov are well known. Kuku is a respected human rights activist. When he was first arrested, he said to his wife, “Now all communication with media and human rights organizations lies on your shoulders.” He told her not to be afraid. “In our world you cannot tell our story if you close yourself off and don’t talk about the pain we are living through.”

That is why Meriem Kuku spoke out. She became a key player in Amnesty International and Frontline Defenders informational campaigns to support political prisoners. Meriem has done this for the past five years. There are seven more years left on her husband’s 12-year sentence.

Lemara Memediminova, now a close friend of Meriem through the support group of wives, also invited the Kyiv Post team into her life over the past year. We were able to capture a unique positive moment on camera: the release of her husband Nariman Memediminov and his reunion with his family after two and half years detention.

Eurasia Center events

The Kyiv Post team faced numerous major challenges in filming this project. It was not possible for our team to physically go to Crimea due to safety issues arising from the ongoing Russian occupation of the peninsula. Finding accredited journalists within Crimea was also impossible as a result of Russia’s persecution of independent voices. All independent journalism has been practically squeezed out of Crimea by the Russian occupation authorities.

People who record events for Crimean Solidarity in courts and during house searches are largely self-taught. Those who have not yet been arrested understand that it is vital to continue documenting the reality of events under Russian occupation.

During the production of the documentary, everyone involved understood the risks that came with filming such a project. Crimean residents have been jailed for multiple years simply for flying a Ukrainian flag or for a facebook “like.” But the activists involved in the documentary value truth and want their stories heard.

The coronavirus pandemic greatly affected the project, restricting already limited contact even more. As a result, we adapted the original concept of the project from a video series following families of political prisoners in depth to a documentary film chronicling how Crimean Solidarity was founded and how the group functions under occupation. Two additional five-minute segments highlight key activists Lutfiye Zhudeiva and Meriem Kuku.

International audiences may have heard about the 2014 takeover of Crimea by “little green men” (Russian soldiers without identifying insignias) but might not necessarily have followed what has happened since. Even people living in Ukraine are often not aware of specific cases of detainment, torture, and murder, or the peaceful resistance movement. Russia intentionally suppresses independent media in order to prevent challenges to the Russian disinformation narrative that Crimea was rightfully returned to Russia and that Crimeans supported the move.

Russia’s ongoing aggression in eastern Ukraine and occupation of Crimea must be a priority for the international community. Russia has repeatedly broken and disregarded foundational UN Charter and Helsinki Act principles. This undermines the security of Europe as a whole and sets a potentially disastrous precedent for the future of international relations in general. Russia’s actions have also caused many human rights violations, subjecting citizens of Crimea to unfair persecution, arrest, torture, and murder.

The aim of this documentary film is to educate those who are not aware of what is happening in Crimea under Russian occupation, and to encourage action from those who have the power to help. We are glad that the UN General Assembly passed two resolutions in December 2020 specifically highlighting Russia’s human rights and security violations in Crimea, but much more is needed. If Russia is allowed to violate international law without consequence, Moscow will continue to push boundaries and claim more victims.

Elina-Alem Kent is the producer of the Kyiv Post documentary “Crimean Solidarity: The fight for freedom in Russian-occupied Crimea.”

Further reading

Eurasia Center events

Image: Image from the recently released Kyiv Post documentary “Crimean Solidarity: The fight for freedom in Russian-occupied Crimea.”