Official Tallies Are Tracking With Polls Predicting a Strong, Pro-Europe and Reformist Coalition

With 71 percent of Ukraine’s ballots counted today, the official results are broadly tracking the recent days’ polls, suggesting that Ukraine’s next government will be a pro-European coalition built across several political parties, with President Petro Poroshenko likely to rely on his alliance with a strengthened Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk. Despite the war in the southeast, and hundreds of thousands of uprooted families, voter turnout was greater than 50 percent, according to the Central Election Commission—a reflection of the popular demands voiced last winter by Ukraine’s pro-democracy, anti-corruption Maidan movement, writes the Atlantic Council’s Irena Chalupa.

As the count proceeds, the election watchdog organization OPORA is updating an interactive map (in Ukrainian) of the results. That map this morning showed turnout (below), ranging from 75 percent along the Polish border in the west to less than 30 percent in government-controlled parts of the southeastern Donbas region.

ANALYSIS: What the vote results suggest so far:

A tougher Ukrainian stance in the conflict with Russia.

Atlantic Council Senior Fellow Adrian Karatnycky is one of four Council analysts watching the vote in Ukraine. “The election was a victory for parties that have staked out tough-minded positions on compromise with Russia and who support a strong and assertive stance on national defense’” Karatnycky writes. This is visible in the better-than-expected performance of Yatsenyuk’s Popular Front and the Samopomich (“Self-Reliance”) party. “Parties that support going the extra mile to seek compromise with Russia did not do as well, especially the Poroshenko bloc,” Karatnycky adds.

The victory of staunch nationalists who are readier to fight than to negotiate with the Russian and Russian-proxy forces occupying southeastern Ukraine may prompt Russian President Vladimir Putin to contemplate an aggressive response, including perhaps a new military offensive in the south, according to John Herbst, the former US ambassador to Ukraine who heads the Atlantic Council’s Eurasia Center. (Read his essay here.)

Karatnycky adds: “The Kremlin will need to understand that its belligerence is leading to the consolidation of support for a vigorous defense of Ukraine’s territorial integrity. Tough, pragmatic politicians who reject deep concessions to Russia have done well.”

Arseniy Yatsenyuk will likely remain as prime minister.

Yatsenyuk’s Popular Front is running virtually even with the Poroshenko Bloc (each with 21 percent) in the party preference race, but this vote represents only half of the election—225 of 450 seats in the Verkhovna Rada. About 200 other seats will be elected in individual districts. In those races, Karatnycky says, “candidates backed by oligarchs and rent-seeking groups are likely to do better, as will the backers of President Petro Poroshenko.” With half of the vote counted, this was making Poroshenko’s group easily the biggest single force in the next Rada. Still, Yatsenyuk remains the strongest candidate as prime minister in the next government. With his help, Poroshenko may achieve a two-thirds majority in the new Rada to permit changing the constitution–a critical ability for the government reform efforts Ukraine needs.

A broad coalition will seek economic, administrative, and anti-corruption reforms.

The strong emergence of the third-place party, Samopomich, is “a sign that people want new faces, many associated with deep reforms, in power,” writes Karatnycky. This party, headed by the liberal mayor of the western city of Lviv, Andriy Sadovyi, “is the only completely fresh force on the ballot, and it came in a strong third,” with 11 percent of the national party-preference vote. The party staunchly backs the goals of the Maidan movement. “Samopomich activists will align with civic activists in the Poroshenko, Batkivshchyna and Popular Front lists to create a new lobby for deep reforms,” Karatnycky adds.

The strong votes for Samopomich and Yatsenyuk’s Popular Front challenge an old pattern in which many post-independence Ukrainians tended to gravitate to a single party loyal to the president of the moment, writes Chalupa. “It shows that the Ukrainian voter is becoming a sophisticated and discerning consumer, no longer wanting or willing to completely trust what has been referred to in Ukraine as the party of power,” she says.

A government coalition of the top three parties “will consist of around 260 deputies which is comparable to the majority that [former President Viktor] Yanukovych once enjoyed,” writes political consultant Brian Mefford, the Council’s Kyiv-based non-resident senior fellow. “Since 226 votes are required to pass any legislation, this gives the coalition some wiggle room” that may allow Poroshenko to exclude from the government his pre-election ally, the nationalist Svoboda party. That room to maneuver is increased because independent members of the Rada will likely join the coalition. “With Poroshenko not wanting to be bogged down in questions about Svoboda’s nationalist positions, it’s an extra reason why he may decide not to invite them to join the government. Independent deputies will stay in the majority without demanding Cabinet posts – unlike Svoboda,” Mefford writes.

Tensions between Poroshenko and Yatsenyuk will increase.

“Under the 2004 Constitution, the post of president is weak except in cases of a war,” writes Mefford. With the war appearing to wind down, Poroshenko’s influence is expected to wane. That, “combined with Yatsenyuk’s strong electoral performance in the elections, means Yatsenyuk’s influence will dramatically increase as the public begins to focus on the economy and social matters rather than security issues. Recent polls have already indicated dissatisfaction with Poroshenko’s handling of the economy despite the fact that the president can do little to affect it under the 2004 Constitution.” While the tensions are not at the level of those between former President Viktor Yushchenko and former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko in the years 2007-2010, “they could quickly escalate,” Mefford says. “In addition, Yatsenyuk will have more influence with parliamentary deputies simply because he can do more political favors for them than the president.”

Constitutional reforms are still possible but more difficult.

“To make the constitutional reforms that Poroshenko has been advocating, he will need 301 votes [in the Rada]. Given his bloc’s less-than-expected performance on the party list ballot yesterday, the math becomes somewhat more difficult,” Mefford writes. “At the very least, he will need to make concessions to Tymoshenko, Svoboda, the Opposition Bloc or Oleh Lyashko’s Radical Party” to pass planned reforms to the government. These include the plan to decentralize some government powers from Kyiv to provincial and local authorities.

The ouster of the Communists is an historic turning point.

The Communist Party is failing to achieve the minimum 5 percent of the national vote to win seats via their party list, and they are not well placed to do well in the district races. Their exclusion from parliament would mark “the first time since the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, including the entire period of Ukraine’s independence, that Communists will be absent from the governing structures” (except for the brief post-Soviet period in which it was banned), writes Chalupa, a longtime journalist in Eastern Europe who directed the Ukrainian service of Radio Free Europe-Radio Liberty. The Communists’ fall is in part the other side of the generational change that one year ago brought hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians, led largely by the younger generation, into the Maidan protests and overturned the corrupt, Moscow-aligned government of former President Viktor Yanukovych. The Communists’ ouster from parliament at will mark “an important psychological moment for Ukraine, one not to be underplayed,” Chalupa writes.

The Opposition Bloc is not likely to be radical in its opposition to the government.

Yanukovych’s former political machine, which once commanded 35 to 40 percent of votes, won less than 10 percent yesterday, in the form of a re-shaped party called the Opposition Bloc. “By taking part in these elections, the Opposition Bloc members made a choice to remain Ukrainian and influence political events,” according to Meffort. “In addition, businessmen do not generally like being in opposition, as it’s bad for business. Given the number of big businessmen in the bloc, they are likely to cut side deals with the government to protect their financial interests rather than resort to radical opposition. That doesn’t mean they won’t oppose the government and majority frequently, but it does mean that it is likely to be modulated.”

Tymoshenko will stay out of government; Lyashko will be isolated.

Other politicians who did not do as well as expected were two of Ukraine’s more populist campaigners: former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko, who thus suffers her second major defeat this year (following the presidential vote in May), and Oleh Lyashko, a nationalist whose vigilante approach to confronting rivals has been criticized by human rights groups.

Tymoshenko is likely to be a part of the new majority while staying out of the govenrment. “Given the bad economy, this gives Tymoshenko a chance to play constructively in public as a coalition supporter but without the baggage of holding cabinet posts during a recession,” says Mefford. She will seek to plan a return to leadership, but “given that her vote performance is less than she received in 2002 when she was an opposition leader against [former President Leonid] Kuchma, her political future does not have a strong upward trajectory any time soon.”

Lyashko lacks allies and is not trusted by the Poroshenko-Yatsenuk coalition, according to Meffort. “Without continued financial support from exiled busines magnate Dmytro Firtash and others, Lyashko’s faction “is likely to start to lose members next year as individuals protect their own interests now that the campaign is over.”

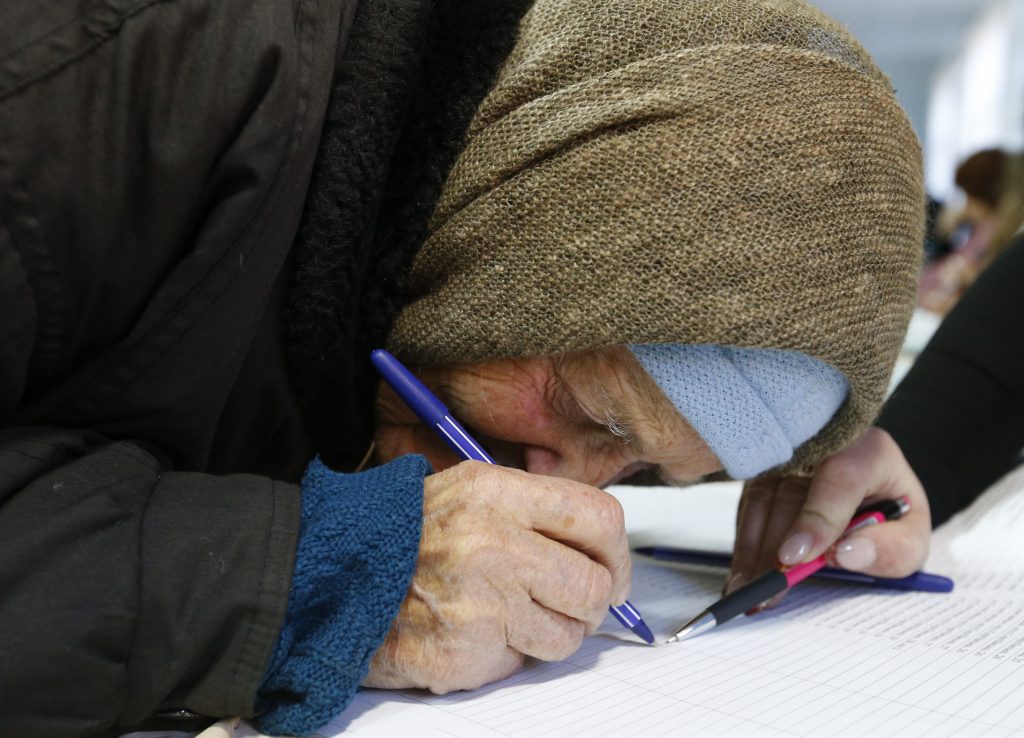

Image: An aged woman in the eastern city of Slaviansk signs to receive her ballot for Ukraine's October 26 parliamentary election. Slaviansk, recaptured by the government from Russian-sponsored rebels last summer, voted with about 90 percent of the country on Sunday. Russian-backed authorities in the Crimean Peninsula and part of the southeastern Donbas region banned the vote. (Reuters/Vasily Fedosenko)