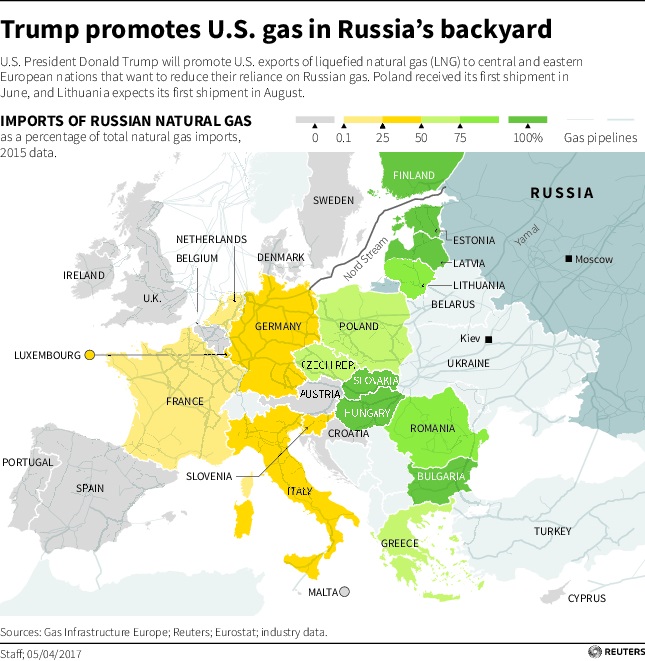

Washington’s got a new way to counter Russian influence in Europe, and it’s not what you might expect. Thanks to new technology, the United States has experienced a boom in natural gas production and is set to become the world’s third-largest exporter of liquefied natural gas (LNG) by 2020. The United States has recognized this opportunity and is increasingly taking a leadership role within global gas markets to challenge Russian gas dominance over Europe. In his remarks in Poland before the G20 summit, President Donald Trump said that the United States will ensure European access to alternative energy sources so that “Poland and its neighbors are never again held hostage to a single supplier of energy,” presumably referring to Russia.

Washington’s got a new way to counter Russian influence in Europe, and it’s not what you might expect. Thanks to new technology, the United States has experienced a boom in natural gas production and is set to become the world’s third-largest exporter of liquefied natural gas (LNG) by 2020. The United States has recognized this opportunity and is increasingly taking a leadership role within global gas markets to challenge Russian gas dominance over Europe. In his remarks in Poland before the G20 summit, President Donald Trump said that the United States will ensure European access to alternative energy sources so that “Poland and its neighbors are never again held hostage to a single supplier of energy,” presumably referring to Russia.

These remarks came after a terse European rebuke of the new US sanctions on Russia that the US Senate passed in June. Since then, Congress has approved the bill and the White House has said Trump will sign it. The bill would subject European companies involved in sanctioned Russian energy projects to US sanctions, too, if the president chooses to activate that provision of the legislation. Germany’s Foreign Minister Sigmar Gabriel and Austrian Chancellor Christian Kern criticized the legislation, saying, “Europe’s energy supply is a matter for Europe, not the United States of America.”

But the deeper cause of energy-related tensions between Europe and the United States recently, and within Europe itself, can be attributed to the Russian-led Nord Stream 2 pipeline project. Russia’s state-owned gas conglomerate Gazprom developed the project to expand the existing Nord Stream pipeline that delivers Russian gas through the Baltic Sea to Europe, bypassing Ukraine and thereby stripping it of transit fees.

The Nord Stream 2 project has been received differently among European states; the largest consumers of Russian gas—Austria, France, and Germany—have supported it, while the Baltic and Nordic states have criticized it, calling it an extension of Russia’s gas monopoly over Europe and a threat to the region’s security.

Agnia Grigas, an expert on global energy markets and a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, masterfully explains the geopolitical underpinnings of this gas triangle between Europe, Russia, and the United States in her latest book, The New Geopolitics of Natural Gas (Harvard University Press, 2017). She describes the intricate global landscape of natural gas markets, with a particular focus on Russia’s use of Gazprom as a political tool against Europe and Eurasia, as well as the new surge of US-led natural gas initiatives across the globe. Grigas details the major gas players, infrastructure, and the geopolitical tensions over energy supplies. Her book tackles dense issues with clarity and is written in a compelling manner.

Even if Nord Stream 2 goes forward, Grigas argues that Russia’s gas dominance over Europe is on the decline. The countries that disagree with the project have been growing in number, bolstered by new opportunities for gas supplies, in particular from the United States. Lithuania built a floating LNG terminal, enabling it to find other suppliers of natural gas, and in 2017, signed an agreement to receive LNG from the United States. Poland has already received its first shipment of American LNG and has signed deals for more. These opportunities and others stemming from the US shale boom and EU’s own energy strategy, driven by goals of diversification, efficiency, and renewables, will provide European countries with more attractive energy partners than Russia, according to Grigas.

Global LNG exports are due to rise by at least 20 percent. This may set up energy competition between the United States and Russia not only over the European markets but also globally. Russia is due to open its third LNG terminal this year, the Yamal LNG Project in the Arctic. If successful, Russian company Novatek could vault Russia—a relative latecomer—into the LNG market, and pit it against the United States.

With a nuanced understanding of the political underpinnings of the market and the implications for US foreign policy, Grigas’ examination provides insight into how this LNG influence may play out and emphasizes the critical role that US energy can take in diversifying European and even Asian markets from Russian gas. The United States can maximize its LNG imports to Europe by capitalizing on the shale revolution and leading in the creation of a new global gas market. The traditional gas market, dominated by Russian pipelines, will no longer be the status quo as new gas players emerge and new relationships are formed.

President Trump has made US natural gas a focal point of his administration. The New Geopolitics of Natural Gas should be required reading for those policymakers hoping to understand its implications on policy and the international order.

Mari Dugas works at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard’s Kennedy School. She tweets @marilisdugas.

Image: The LNG tanker "Clean Ocean" is pictured during the first US delivery of liquefied natural gas to LNG terminal in Swinoujscie, Poland, on June 8, 2017. Agencja Gazata/Cezary Aszkielowicz via Reuters