The Atlantic Council’s UkraineAlert recent published an article by Anders Aslund critical of the October 2019 RAND report “A Consensus Proposal for a Revised Regional Order in Post-Soviet Europe and Eurasia”. This is a response from two of the report’s authors.

We would like to thank Anders Aslund for reading and commenting on the RAND publication that we co-authored along with 19 others from the United States, Russia, the EU, and the states in-between. The article he wrote in response to our report deserves an answer – not only because he is such a prominent voice on Russia from whom we both have learned much, but also because his piece raises arguments we often hear.

Anders’s problem with the report is less with its specific content than with the very idea of the exercise. We and our co-authors have put forward, as the title suggests, a “compromise proposal” for revising the regional order in Eastern Europe. Compromise is, by its nature, a dirty business. It involves the painful task of separating out what you really need from what you merely want or aspire to accomplish. It requires understanding the perspectives and fears of those sitting across the table from you, even if you loathe them. On politically fraught subjects such as this one, just describing the possibility of compromise opens one up to charges of appeasement and betrayal, which is why so few people do it. Indeed, many of the fiercer reactions to the report have reminded us of the political wisdom of adhering strictly to the orthodoxy on this subject.

Stay updated

As the world watches the Russian invasion of Ukraine unfold, UkraineAlert delivers the best Atlantic Council expert insight and analysis on Ukraine twice a week directly to your inbox.

But of course, compromise is also the essence of diplomacy, the only way short of coercion, violence, and war of settling international disputes. As the report notes, none of the 21 authors got everything they wanted in this exercise. None loved the often-anodyne language or would see this proposal as an ideal outcome. But they could all accept it. The main value of the report resides in showing that 21 experts, each channelling their own and their nations’ perspectives, could agree. The proposal is not a panacea. We don’t see it as immutable or perfect in its every detail. We see it as a demonstration of what is possible, an exercise in showing that such a compromise exists if only leaders from across the region have the courage to seek it.

Anders suggests that Track 2 efforts should be about “identifying key dividing lines” and “the real differences between Russia’s and the West’s aspirations.” In our view, the “first track” (i.e. government-to-government) has mastered the art of identifying the key dividing lines and the real differences. For example, just watch any press conference featuring the Russian foreign minister and a Western counterpart, and you will hear a comprehensive list of disagreements. Since the role of the second track is to do what the first cannot, we see no need to replicate this recitation of mutual grievances. Track 2 initiatives exist precisely to go beyond what the governments are already doing and explore issues that might be too sensitive for them to address.

In our project, we tried to replicate as best as possible the dynamics of an official multilateral negotiation. By definition, this involves avoiding assigning blame for past sins. For Anders, the essence of any diplomatic outreach with Russia must begin by describing the “reality” of the situation in Eastern Europe, by which he means forcing Russia to accept that it is the guilty party in the many economic and political conflicts roiling the region. It would not be difficult to find similar thinking in Moscow, albeit with a different guilty party identified.

The two of us would almost certainly agree more with Anders than with his counterparts in Moscow on the perennial question of “who is to blame.” But you negotiate with your adversaries, not with your friends. Insisting that your adversaries accept your narrative and renounce their own before you negotiate is not diplomacy. It is war by other means. And, as our report notes, history, including the history of the Cold War, suggests that a common narrative among parties to a negotiation is not necessary to reach compromises that can enhance stability and prosperity.

Eurasia Center events

That same Cold War history offers an additional lesson: not every adversary is akin to Nazi Germany. If Anders’s dictum that “to try to reach any consensus with the enemies of democracy should be considered as indecent today as it was in Munich in 1938” would have been upheld during the Cold War, there would have been no negotiating with the Soviet Union at all. In fact, not only were negotiations key to stabilizing the superpower rivalry and avoiding nuclear Armageddon, but also the successful end of the Cold War was itself a product of extensive negotiations.

Anders prefers to stand above this dirty business of diplomacy and to insist that no compromise with Russia is possible. He may be right, of course. Certainly, if everyone in Moscow and Washington takes his view it will become a self-fulfilling prophesy. But before we accept that, let’s first understand the cost of the new Cold War with Russia that would result. The original Cold War cost many trillions of dollars, killed millions of people around the globe, eroded US civil liberties at home, and forced two generations of children to live under the constant threat of nuclear annihilation. That it ended peacefully is something of a geopolitical miracle. It would be foolish to expect that such a miracle would repeat itself. Given the rise of China, choosing to fight such a new Cold War would represent diplomatic malpractice.

Before accepting that disastrous outcome, we prefer to explore the possibility of compromise, even if, for many in Washington, it is always 1938. Before we tell the peoples of the in-between countries that they are condemned to serve as battlefields in a multi-generational struggle between the forces of good and evil, we prefer to see if we can find a way to offer them a path to security and prosperity. Before we condemn ourselves to another Cold War that only China can win, we prefer to explore whether we can have a stable competition with Russia.

Samuel Charap is a senior political scientist at the nonprofit, nonpartisan RAND Corporation. Jeremy Shapiro is the director of research at the European Council on Foreign Relations. They, along with 19 others, are among the contributors to the report “A Consensus Proposal for a Revised Regional Order in Post-Soviet Europe and Eurasia” published by RAND in October 2019

Further reading

The views expressed in UkraineAlert are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Atlantic Council, its staff, or its supporters.

The Eurasia Center’s mission is to enhance transatlantic cooperation in promoting stability, democratic values and prosperity in Eurasia, from Eastern Europe and Turkey in the West to the Caucasus, Russia and Central Asia in the East.

Follow us on social media

and support our work

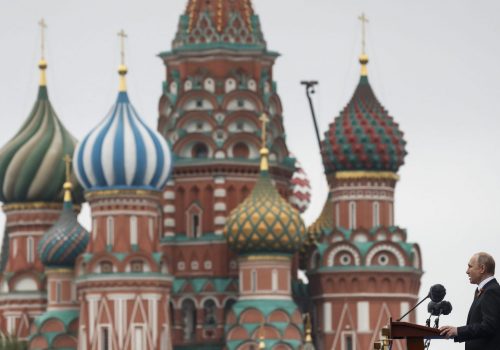

Image: Russian President Vladimir Putin makes his annual New Year address to the nation in Moscow, Russia December 31, 2019. Sputnik/Mikhail Klimentyev/Kremlin via REUTERS