An intellectual reckoning on counterterrorism

The time has come for the US counterterrorism community to undertake a difficult and probably painful review of whether the United States’ current practices and investments are sufficiently advancing its strategic interests and policy goals against terrorism. For far too long, and still today, this community and the policy makers that oversee it have flinched from sufficiently doing so.

The deeply emotional and importantly historical remembrance that Americans share on another commemoration of the September 11, 2001, attacks should never become mundane or dwindle in the American collective consciousness. The horror of that day, now two decades ago, should always be reason to remember, reflect, and certainly mourn, but also to celebrate all that the United States has endured and achieved in its ongoing struggle with terrorism. That said, it should also be a reminder that sober reflection and self-examination are in order.

Those of us who served in the counterterrorism mission for many years and our policy makers should use 9/11 as a catalyst to dispassionately and critically take stock of all that the United States has gotten right, and what it has gotten wrong.

Over the past twenty years, it has become increasingly clear that, for all the major triumphs and tremendous tactical and operational improvements in counterterrorism capabilities and efforts since 9/11, the spread and growth of all forms of violent extremism—not just the type that attacked us two decades ago—has continued unabated, regardless of the extraordinary efforts globally and domestically since that terrible day. For years, virtually all public and private indices that strive to record the volume of terrorist violence, or the number of terrorists committing such acts, have reported continued expansion of this phenomenon.

Yet, how can this be? Consider the sustained and large expenditures by the US government toward creating far more robust, precise, and, in some cases, breathtaking abilities to identify, track, target, and—by either law enforcement or military means—end a terrorist’s activity or threat. The degree of practitioner and organizational skill developed across the US intelligence community, the military, and law enforcement agencies has been a revolution in everything from tactical skill to interagency collaboration. Also, the collaborative networks and combined efforts the United States has established with like-minded allies and partners around the globe has created consistent operational successes that have served the United States well in every major counterterrorism campaign it has undertaken. And, just as importantly, the American people have become supremely confident in their nation’s ability to conduct highly precise counterterrorism apprehensions, kinetic strikes, and long-range raids such as those that killed Osama bin Laden or Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. This is why it is often troubling, confusing, or simply disagreeable for either US citizenry or policy makers to be confronted with any assertion that, despite all the progress made, the terrorism problem has only become larger, more diverse, more widespread, and more dangerous.

The key to unlocking this confusion and disappointment lies in the difficult acknowledgement that the US government has consistently misapprehended what kinds of “effects” various counterterrorism endeavors are most likely to create.

First, too many counterterrorism practitioners have failed to grasp what the most likely strategic effects will be from the skills and tools that the United States has invested most heavily in—what most in the counterterrorism community describe as “kinetic CT” capabilities and operations.

During my time at the National Counterterrorism Center, my directorate conducted an annual, whole-of-government assessment of how the US government spends “CT dollars.” Every year, the directorate reported that the vast preponderance of these funds are spent toward the United States’ ability to gather intelligence, target, and then use either law enforcement or military capabilities and personnel to apprehend, capture, and, if necessary, use lethal force against terrorists. And, of course, this is done with the goal of minimum collateral damage and a maximum amount of international, coalition, and allied collaboration. These improvements have led to two important outcomes: first, they have saved thousands of lives by preventing terrorist attacks, and second, they have brought tens of thousands of terrorists to some form of justice, whether as casualties on a lawful battlefield, or properly sentenced in a court of law.

Unfortunately, too many counterterrorism practitioners and policy makers alike make the mistake of assuming these kinetically obtained results will, over time, strategically and durably reduce the scale or scope of terrorism. Twenty years after 9/11, we have abundant empirical evidence that, while kinetic counterterrorism can substantially suppress terrorism for a period, the phenomenon will inevitably rebound and resume its growth trajectory.

Second, a substantial body of both counterterrorism and counterinsurgency (COIN) literature since 9/11 typically conveys that the use of kinetic instruments, while often necessary in these types of struggles, only buys “time and space” for other, primarily civilian efforts. In concept, these “non-kinetic CT” civilian efforts must be the principal means by which we undo the various political, societal, ideological, religious, and/or cultural conditions that foster the emergence and spread of terrorism.

Accordingly, many of the strategy and policy pronouncements the United States has made since 9/11 often acknowledge the importance of non-kinetic counterterrorism, and make various assertions about the importance of applying these civilian agencies and instruments to address the “drivers” or “conditions” that foster terrorism. Yet, the examinations I once oversaw on expenditures for non-kinetic counterterrorism also made clear that these civilian-oriented organizations and activities receive a tiny fraction of what the United States annually provides for kinetic counterterrorism. These examinations also illuminated how many extraordinarily skilled and courageous Foreign Service Officers, USAID practitioners, messaging and information operations operators, and other “non-kinetic” practitioners and leaders are too often underappreciated, undervalued, and perennially receive neither the resources nor the kinds of sustained and risk-tolerant policy support that kinetic counterterrorism practitioners have become accustomed to. This largely explains why kinetic counterterrorism practitioners like me eventually came to call our kinetic counterterrorism operations as being akin to “mowing the grass.” The grass always comes back.

On this year’s 9/11 remembrance, Americans have another opportunity to seriously reflect on that imbalance, and hopefully begin the difficult but necessary journey to address it, and ultimately put it right. Here are four suggested areas on which to focus.

Twenty years after 9/11, we have abundant empirical evidence that, while kinetic counterterrorism can substantially suppress terrorism for a period, the phenomenon will inevitably rebound and resume its growth trajectory.

First, US practitioners and policy makers must acknowledge, both internally and publicly to the American people, that the nation has an increasingly dangerous imbalance between investment in and conduct of kinetic versus non-kinetic counterterrorism efforts. This will be embarrassing and painful, but a failure to acknowledge the imbalance reduces the likelihood that the nation will collectively or effectively address it.

Second, building on that acknowledgement, both policy makers and congressional leaders alike should engage with the complex and difficult question of correcting this past failure. Certainly, decisionmakers should keep in mind the intent of Hippocrates, “first, do no harm” to current US strengths in kinetic counterterrorism. Those abilities should be sustained and, when necessary, improved. However, the priority now should be to undertake what will inevitably be a long, difficult, and complex journey to provide stronger policy support and resourcing to the dozens of organizations and thousands of practitioners, at the federal, state, and local levels, who strive to conduct, both domestically and internationally, missions such as these:

- Terrorism prevention, often called Countering Violent Extremism (CVE), which focuses on official and nonofficial government-to-local activities necessary to substantially reduce the appeal of terrorism and the rate and volume at which people are enticed either to join the ranks of or provide direct or indirect support to violent movements.

- Information activities, operations, messaging, and counter-messaging, which increasingly include cyber-related activities within the open, deep, and dark parts of the Internet. As the world moves ever deeper into the digital age, terrorism propagandizing, recruitment, planning, and operational activity will correspondingly shift into the digital arena. Perhaps most importantly, we must recognize that it is impossible to fully remove or contest the ever-growing volume of these nefarious online activities, and, therefore, one of the greatest needs is for the United States and its allies and partners to become far more competitively persuasive in these arenas than the terrorist adversaries who are vying for the affections and confidence of the same people.

Third, counterterrorism-related capabilities and capacities of US entities such as the Foreign Service, USAID, the US Agency for Global Media, and the Global Engagement Center should be built as they strive to contest the growing global trends of diminishing popular confidence in democratic governance. History amply demonstrates that this erosion always creates a rich breeding ground for violent extremism. This must also encompass the need for more effective efforts by government to enable and support state and local leaders and actors, in both public and private sectors, to effectively stem the growing tide of domestic terrorism in the United States. Across the board, we must fund more research to diagnose the reasons for its growth and test potential remedies, examine our existing approaches, create and experiment with new ones, and all while simultaneously assuring American citizens that their constitutional rights and civil liberties will not be threatened.

Fourth, the US government needs to foster far greater policy maker “risk tolerance” for non-kinetic counterterrorism activities. Ironically, US policy makers historically demonstrated an impressive willingness to accept the strategic and operational risks involved with killing or capturing terrorists, even when these risk substantial US operational casualties, or where kinetic counterterrorism might tragically and inadvertently harm innocent bystanders or civilian infrastructure. Yet, non-kinetic counterterrorism practitioners in arenas such as post-combat stabilization work, terrorism prevention activities, messaging and cyber operations, economic and foreign assistance, and the like often must operate in a “zero-defect” climate because of policy maker intolerance for risk. This perversely, but consistently, reduces the likelihood that sufficient numbers of talented practitioners will be attracted to such work, and correspondingly reduces the likelihood that existing practitioners will be willing to spend a career doing so because they feel constantly “second-guessed” by those that are supposed to support and nourish their efforts.

None of the foregoing is pleasant to acknowledge. Certainly, none of it is intended to diminish or criticize all that the United States has accomplished, at the cost of significant blood and treasure, since 9/11. Most importantly, like all my former military and civilian counterterrorism colleagues that I served with in so many far-flung places, I celebrate on 9/11 the important accomplishments that have been achieved, while mourning those lost or who have suffered grievously as the price for defending the American people and all that we hold dear.

Yet, we owe it to our fellow citizens, and our children and generations yet unborn, to do the hard work of taking stock of what we must still do. Terrorism continues to thrive, and in too many places to grow, and we still have not found or achieved the right balance between kinetic and non-kinetic approaches against it. Finding that balance will never be perfect, but it is not yet good enough. As the nation looks back on all that has been done since 9/11, we need to recognize what we still must do, and recommit ourselves to achieving it.

* * *

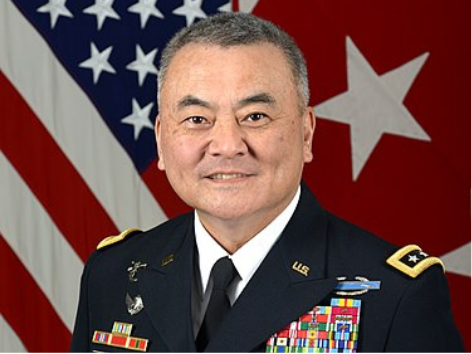

Michael Nagata

LTG Michael Nagata (Ret.) currently serves as CACI’s Corporate Strategic Advisor. Prior to this, he served 38 years in the active duty US Army, with 34 years in US Special Operations. His final positions in the Army were Director of Strategy for the National Counterterrorism Center, and Commander of Special Operations Command, Central (USSOCCENT). While USSOCCENT Commander, he was heavily involved in the first two years of combat operations against the Islamic State in Iraq, Syria, and elsewhere. LTG Nagata (Ret) also served in the US Intelligence Community as a Military Deputy for Counterterrorism. Additionally, he served as the Deputy Chief in the Office of the Defense Representative at the US Embassy in Pakistan, and as the Deputy Director for Special Operations and Counterterrorism at the Joint Staff in Washington, DC.

Generously Supported By

Explore “The future of counterterrorism” series

Engage with our series as we continue forecasting the future of counterterrorism

Learn more about the Middle East Programs

Learn more about Forward Defense

Forward Defense, housed within the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security, generates ideas and connects stakeholders in the defense ecosystem to promote an enduring military advantage for the United States, its allies, and partners. Our work identifies the defense strategies, capabilities, and resources the United States needs to deter and, if necessary, prevail in future conflict.