This piece is the first in a series examining the opportunities and challenges facing the recently launched “Coal Exit Commission” in Germany. It will shed some light on the context surrounding the establishment of the Commission and explain the important role coal still plays in Germany.

Amid political turmoil over migration, last month Germany launched its so-called coal exit commission, designated to determine an end date for coal use in Germany. The Commission, whose membership was formally announced in late June amid a political spat between Chancellor Merkel and Interior Minister Horst Seehofer over control of Germany’s borders, will hold its first plenary meeting this Friday.

This meeting, and those to follow, represents an important milestone in Germany’s quest for climate leadership. It also appears to be perceived as a litmus test for whether Germany can prove that economic growth and emissions reductions can go hand in hand—and a nod to Environment Minister Svenja Schulze’s commitment to a “socially just transition” made at the St. Petersburg dialogue in Berlin late last month.

The Commission’s origins are in Germany’s 2050 Climate Action Plan, and while the goal is ostensibly to manage the phaseout of coal-fired power production, as the full name, “The Special Commission on Growth, Structural Economic Change and Employment” suggests, the goal is also to manage the potential social and economic dislocation for the coal industry, and communities that rely on it.

The Commission, comprised of representatives from the coal industry, federal and state governments, environmental NGOs, academia, and labor unions, is tasked with providing recommendations by the end of the year for closing the gap between Germany’s 2020 climate target and the present reality, as well as tackling the challenge of meeting Germany’s 2030 climate goals.

On the face of it, the establishment of the Commission is a very positive development.

Germany has long been seen as a leader in the fight against climate change but it has recently faced increasing criticism for its apparent failure to meet its 2020 emissions targets. While the official target is 40 percent emission reductions compared to 1990 levels, current estimates only range from 30 to 33 percent. A coal phase-out certainly helps to close this environmental gap, but the Commission will also have to find ways to soften the social, economic, and energy-related impacts it will cause.

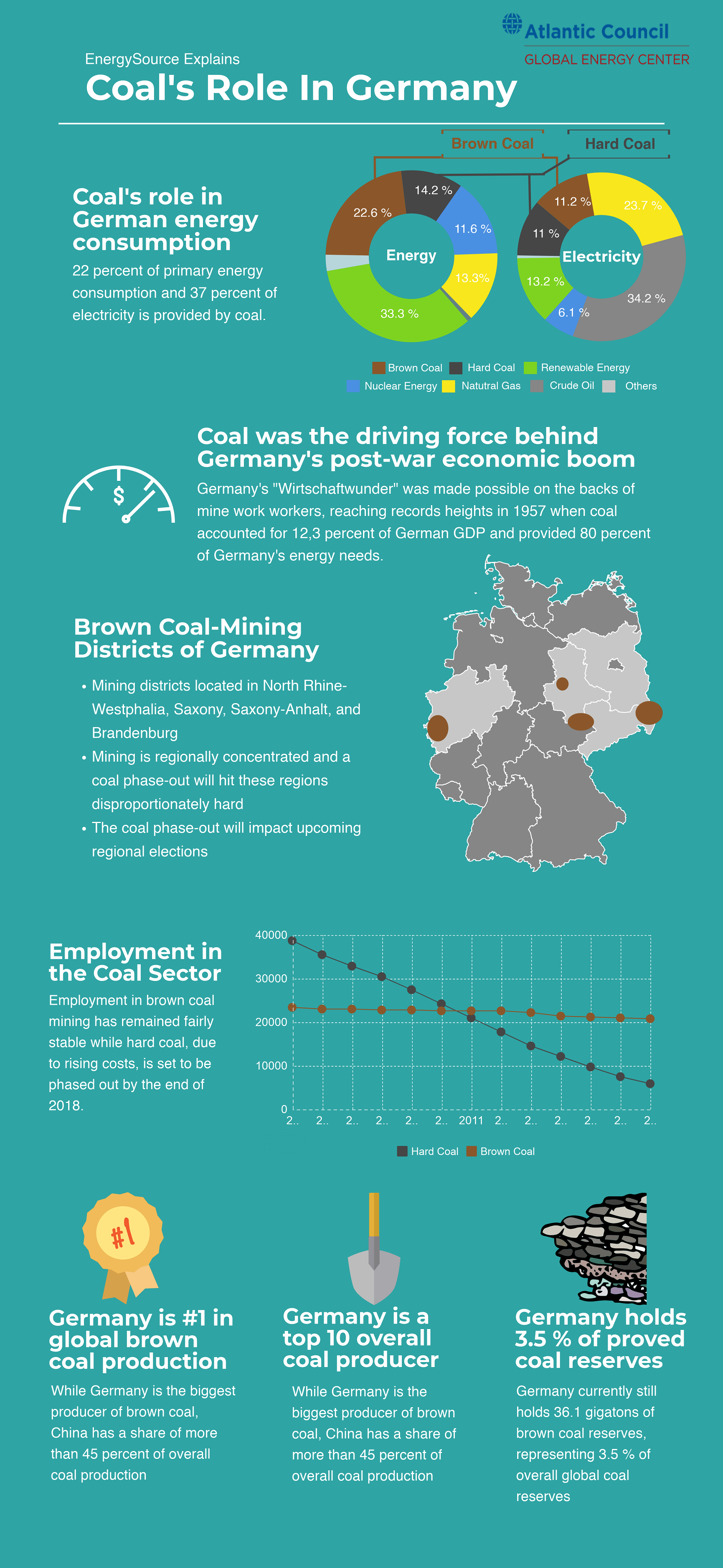

While much of the public stands behind Germany’s climate goals, navigating the social and economic aspects of the transition could be politically tricky, particularly given the shaky state of the current governing coalition. Coal has long been a fixture in Germany, as it powered the economic renaissance after World War II and still holds sentimental value among some German voters for being the backbone of the economy; the engine behind the Wirtschaftswunder, or economic miracle; and a key employer in some German states.

Critically, Germany is still the world’s biggest producer of lignite and coal provides 22 percent of primary domestic energy consumption and, at 37 percent, it remains the main source of electricity.

While Berlin has decided to close the last-remaining hard coal mines by 2018 due to growing costs, the three brown coal mining districts—Rhenish district in North Rhine-Westphalia, the Central German district in Saxony and Saxony-Anhalt, and the Lusatian district in Brandenburg and Saxony—produced 171.5 million tons of brown coal and employed between 13,000 and 21,000 workers in 2017.

Thus, the commission will have to grapple with the challenge of how to soften the economic and social dislocation in key German states while simultaneously accounting for the loss of a critical—and fairly stable and reliable—portion of domestic energy production.

While the commission is just in the opening stages, there are a few things worth noting.

First, the name of the commission, first outlined in the 2050 Climate Action Plan, has evolved, from a commission for growth, structural economic change, and regional development, to include employment, and the choice was made to house it in the energy and economy ministry versus the environment ministry, notable in that the two have often battled over jurisdiction over Energiewende related issues.

Second, the Commission intends to release an interim report on structural change this fall, followed by a report in December on climate change, as the COP24 conference will take place in neighboring Poland, where coal also plays a large role in the domestic economy and energy mix.

Third, the stakeholder model employed for the coal phase out could be applied to other sectors facing both climate challenges and transition in Germany, including in transportation. Key questions will be who bears the cost of transition and who will suffer the penalties if Germany does not meet its climate goals.

Fourth, given the diverse and large composition of the Commission, consisting of thirty-one members with diverse and contrasting views on the pace of the phaseout and the priorities of the Commission, it is difficult to assess what direction it will take—and how ambitious or effective it might be. However, it is safe to say that a lot of coordination and mediation awaits the chairs in order to meet the tight timeline.

Ultimately, Friday will be the first of many difficult conversations, and one that could set the tone for how many countries view the energy transition, especially when a successful transition involves harm—or even an end—to domestic industries once viewed as critical.

You can read the second piece in the series here.

Ellen Scholl is deputy director and Peter Freudenstein is an intern at the Atlantic Council Global Energy Center. You can follow Ellen (@EllenScholl) and Peter (@p_freudenstein) on Twitter