This piece is the second in a series examining the opportunities and challenges facing the recently launched “Coal Exit Commission” in Germany. You can read the first piece here.

Earlier this month, former vice president and climate campaigner Al Gore delivered a tough message to Germany, calling the country’s narrative of climate leadership “out of date.” And while Environment Minister Svenja Schulze acknowledged Gore’s statement, she responded that she plans to bring Germany back on track as soon as possible. With coal still playing a key role in the country’s energy mix, many climate advocates have emphasized that the recently established coal phase out commission can serve as a vehicle for Germany reclaim the mantle of climate leadership.

That leadership is currently lagging behind.

Germany’s emissions reductions have slowed significantly in the last few years. What started off as a promising undertaking, with annual average emissions reductions of 21 million tons from 1990 to 2000, slowed to 5.7 million tons emissions reduction between 2010 and 2017, a record low annual average. Sustained economic and population growth, low carbon prices, low fuel prices, and continued energy-intensive heating suggest that this trend is here to stay.

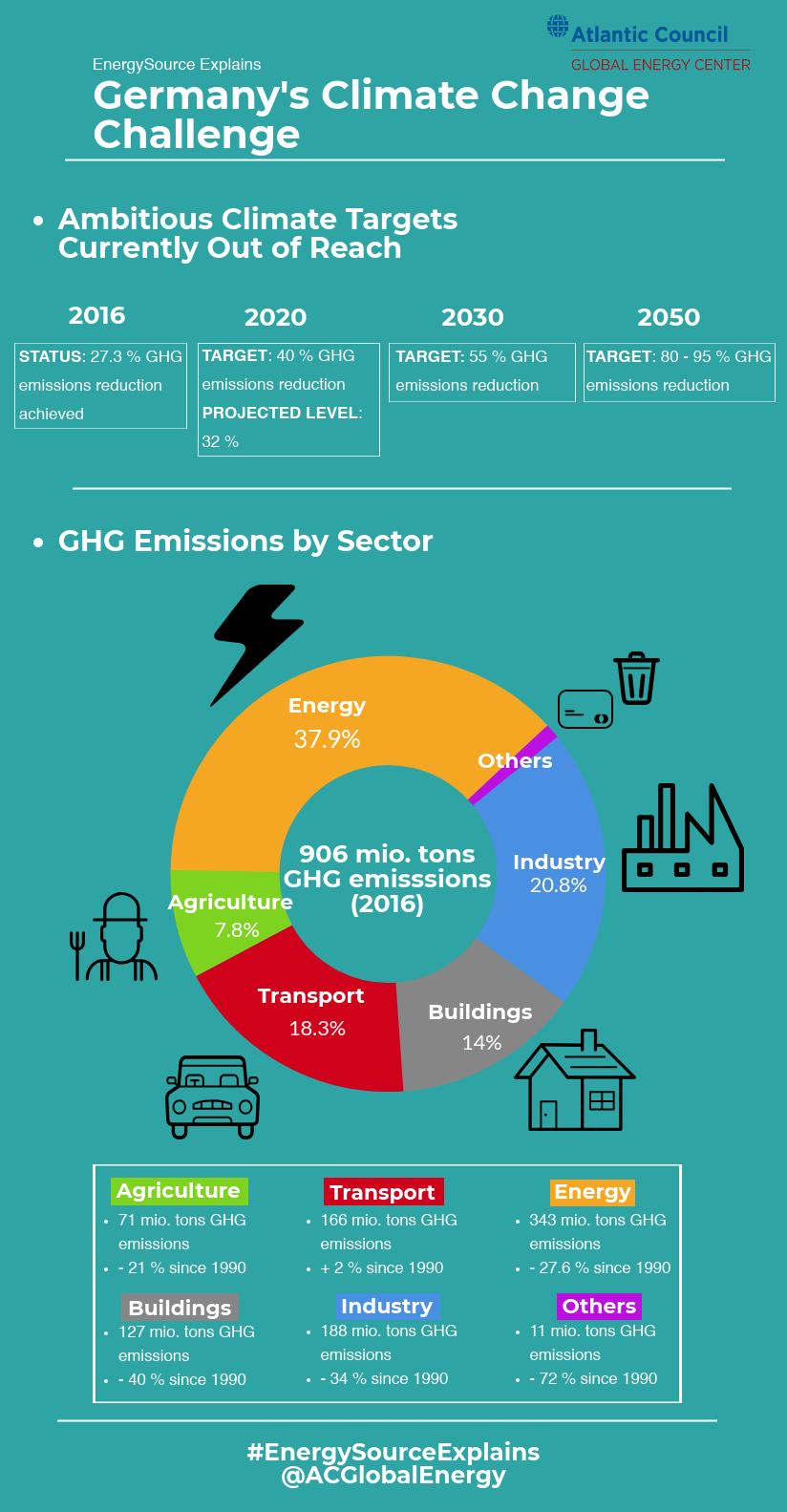

As a result, Berlin is set to miss its 2020 emissions reduction target of 40 percent compared to 1990 levels, by 8 percent. While the official “climate protection report 2017” released this June still clings to the 2020 target, the language and the seventeen months left to go suggest the government has shifted its focus to achieving the mid- to long-term goals instead. Thus, the phase out of coal is part of achieving the 2030 goal of 55 percent emission reduction by 2030, and the 2050 goal of an 80 to 95 percent reduction.

Reliance on coal is often highlighted as the stain on the German energy transition reputation, undermining impressive gains in renewable energy deployment and contributing to a mediocre climate performance in recent years. Germany is Europe’s largest coal-fired energy consumer, still running around 150 coal power plants even as many fellow European Union member states are coal-free or have announced coal phase-out deadlines.

Thus, the establishment of the commission was seen as a welcome—and overdue—development. Yet, the fact that climate change only ranks fourth on the list of tasks of the commission—job creation, economic growth, and financing of structural change are listed first—suggests that climate change could be more of an addendum than a main priority. The significance of the commission is thus twofold: to reduce energy sector emissions and bolster Germany’s climate credentials and to serve as proof of concept for a stakeholder model to navigate the social and economic challenges of the energy transition.

However, when it comes to climate, even if the coal commission succeeds, any phase out will likely be too late to have any impact on short term goals, while meeting long term decarbonization goals will require much more than just cutting coal, even as it raises questions of how to replace or account for the large role it currently plays in Germany’s energy mix.

While the energy sector accounts for a large portion of Germany’s emissions at 38 percent, industry, transport, buildings, and agriculture are also major contributors. Cutting coal will help decrease emissions substantially, but there is still a long way to go to get to 55 percent emissions reduction, let alone long-term decarbonization. A lack of attention to key sectors like buildings and transportation could render the commission’s work necessary but insufficient. However, the commission can serve as a case study for future commissions, with talks on the establishment of similar transition commissions for buildings and transportation already underway.

Additionally, coal’s still substantial role in Germany’s energy mix, accounting for 22 percent of primary energy consumption and 37 percent of electricity, raises energy security questions. Under a successful phase out, that generation will need to be replaced or energy efficiency improved dramatically. This is on top of the need to fill the gap from the phase out of nuclear power, which just grew to 12.7 percent of primary energy consumption compared to last year’s 11.5 percent. The phase out, decided in the wake of the Fukushima nuclear accident in Japan, is set to be complete by 2022.

Moreover, while many point to natural gas as a potential source of cleaner-burning power, Germany’s reliance on Russian gas imports is already a fraught topic amongst both other EU member states and the United States. This contention is particularly acute when it comes to Germany’s plans to increase imports of Russian gas through the planned Nord Stream 2 pipeline project. The German Energy Agency (dena) estimates that the capacity of gas power plants needs to increase from 30 gigawatts (GW) in 2015 to 56-75 GW in 2030, a gap potentially to be filled by this contentious project.

Given these constraints, the combination of energy efficiency and new energy technology could emerge as key to Germany’s climate conundrum. Energy efficiency gains cause a decrease energy consumption, and thus a decrease in emissions, lower energy bills for consumers, and increased energy security. Berlin set an ambitious goal of 2 percent annual energy efficiency increases, but, unfortunately, projections show only an annual 1 percent improvement for the coming decades. Whether the coal phase out goes smoothly or not, major energy efficiency efforts are required to reclaim the mantle of climate leadership.

While a silver bullet for climate change and energy security does not exist, environmental and renewable energy associations argue that the introduction of more renewable energy would solve most problems: using cheap, clean, and readily available technology would easily and reliably replace the current overcapacity in coal and reduce CO2 emissions. A study by the German Energy Agency (dena) assigns a very high importance to the role of renewables and synthetic gas in achieving the goal of 95 percent emissions reduction by 2050 while simultaneously ensuring energy security, potentially killing two birds with one stone.

However, this will not come without a cost and concerted effort, as ultimate decarbonization requires huge financial investments to spur innovation. The Federation of German Industries (BDI) estimates that €1.5 to 2.3 trillion of additional capital by 2050 is needed to achieve the 2050 climate goals. As of now, however, this goes beyond the scope of the commission’s mandate as defined by the German government.

Germany similarly used a commission model to enact its nearly completed Atomausstieg, or nuclear exit, employing one commission to ensure reliable energy supply and a second to evaluate the financing of the nuclear phase. While this process has not been without controversy, the consensus-drive stakeholder model combined with expert recommendation approach can be reasonably called a success. The share of nuclear power was reduced from 22.2 percent in 2010 to 12.7 percent currently, while renewable power generation surpassed that of coal for the first time on July 10 this year, and supply was never in jeopardy.

Thus, while Germany may have challenges ahead, the know-how gained since 2011 combined with political will and the potential carrot of compensation for coal communities seem likely to drive the coal commission over the finish line. However, while the variety of stakeholders represented could lay the groundwork for a broadly sustainable solution, it raises questions: on what time scale and at what cost will Germany’s reclaimed climate leadership come?

Ellen Scholl is deputy director and Peter Freudenstein is an intern at the Atlantic Council Global Energy Center. You can follow Ellen (@EllenScholl) and Peter (@p_freudenstein) on Twitter