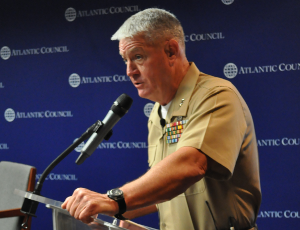

With ISAF’s withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2014 fast approaching, it is useful to look back and see what failures and successes there have been. Have certain challenges been overcome? How do the Afghans see ISAF’s mission? On April 17, the Atlantic Council’s Brent Scowcroft Center on International Security hosted Major General Charles Gurganus, commanding general, I Marine Expeditionary Force (Forward), and his deputy, Brigadier Stuart Skeates of the United Kingdom, to provide an after action report on their mission at Regional Command-Southwest, Afghanistan last year.

At the event, Major General Gurganus outlined the major challenges that the coalition forces, as well as the Afghan forces, still face after a decade of war. He claimed that his region of Afghanistan was now much better off due to his troops’ efforts. After his remarks, he took questions from moderator Shuja Nawaz, director of the South Asia Center at the Atlantic Council, and the audience.

In order to frame the discussion, Lieutenant Colonel Peter Dillon, US Marine fellow at the Atlantic Council, noted first that southwest Afghanistan is a complex and dynamic environment where coalition forces lead a counterinsurgency campaign while working on the transition to enable Afghan forces to take over. Currently, 15,000 military personnel from nine countries form the coalition forces in the region.

The biggest problem in the region, according to Major General Gurganus, is the insurgency. Part of it is still Taliban, but another part is not. “One of the things that continue to fuel the insurgency is the fact that there is about an 85 to 90 percent illiteracy rate” in the region. This situation makes it difficult for the people to make up their own mind, and “it makes it very difficult to train policemen when they can’t read.” However, Major General Gurganus recognizes that progress has been made on this front since the beginning of the war. In 2002, he said, about 800 people were attending school. Today, there are “about 140,000 regularly going to school, and about 28 percent of those are female.” Building more schools is not the primary concern now, but keeping the children going to school is a long-term solution for the country’s enduring development.

The biggest problem in the region, according to Major General Gurganus, is the insurgency. Part of it is still Taliban, but another part is not. “One of the things that continue to fuel the insurgency is the fact that there is about an 85 to 90 percent illiteracy rate” in the region. This situation makes it difficult for the people to make up their own mind, and “it makes it very difficult to train policemen when they can’t read.” However, Major General Gurganus recognizes that progress has been made on this front since the beginning of the war. In 2002, he said, about 800 people were attending school. Today, there are “about 140,000 regularly going to school, and about 28 percent of those are female.” Building more schools is not the primary concern now, but keeping the children going to school is a long-term solution for the country’s enduring development.

It was also pointed out that it is hard to differentiate between criminal activity and insurgent activity, as often the interests are the same. Major General Gurganus urged for caution in defining insurgency. “It is a symptom of struggle for influence over a population.” This will not change in the future, according to Gurganus, but a strong government and strong Afghan forces will prevent it from flourishing. In the last two or three years, the government, particularly at the district level, has shown much progress. There are now seven elected district community councils in the region. One of them held reelection in September 2012. Of the 3,500 people registered to vote, 3,000 showed up to cast their ballot. Happily, one of the winners was a woman. “This is highly significant,” Gurganus added.

The second challenge that Gurganus mentioned concerned the transition. Allowing the Afghan forces to take the lead means “moving more into a partnering, moving more into an advising, more into a mentoring role.” He acknowledged that the task of advising combat units was completed. “They’re about as good as they need to be, and it is going to take an institutional solution to continue to develop” them. Leadership development and leadership training is the next step to build a stronger officer corps. Training people to maintain the facilities built by the coalition is also essential. The Afghan forces have to be able to sustain their logistics. “Developing and trying to improve those institutions now will be the primary focus that you will see in the course of the next eighteen months or so.”

Gurganus highlighted the fact that the number of American casualties dropped dramatically since NATO forces moved into an advice and middle-role, whereas the Afghan casualties went up tremendously.

Questions raised by the audience touched upon the future of the country. For example, what happens after ISAF and the United States leaves? Brigadier Skeates warned against the misconception that in 2014, NATO forces would leave and cut all ties with the Afghans. Major General Gurganus insisted on the fact that “drawing down the forces in a counterinsurgency was just part of the counterinsurgency. There comes a point in time when you have to start handing over the security responsibilities to the indigenous forces.” Gurganus continued claiming that “to win this, it has to be on the backs of the Afghans themselves, and victory is not even completely in the hands of their security forces. This insurgency is over when the people in Afghanistan say this insurgency is over.”

Coordination, claimed Gurganus, is essential: “as we step back, then they step forward.” Letting the Afghans take the lead does not mean abandoning them, however: “They might get their knees skinned but we won’t let them get their nose broken.” The coalition forces continue to help them with the planning, but have stopped telling the Afghan forces how to lead an operation. The United States still provides support when it comes to precision fires, medical treatment, analyzing intelligence, and buying of “gadgets that save lives” like mine detectors.

During the question and answer session, an audience member asked if there was a risk that the Taliban might have strategically decided to lay low for now, before rising again after 2014. “I’m not overly concerned that Taliban can come back in strength and reduce what has been done,” said Major General Gurganus. The Afghan population is more resilient than they are portrayed, according to the two ISAF officials. For them, it is wrong to think that Afghans will fall back easily into the Taliban’s arms. “There is a genuine thirst to continue what has been started over the last few years. They are eager to take ownership on it.” The rule of law, access to justice, or principles of civil society are now desired where they were not before. Encouragingly, the speakers mentioned that they regularly witness Afghan people physically chase insurgents out of their town.

“A lot has been done, but there is still more to do,” concluded Gurganus. Economic development is needed. The infrastructure is poor. But in order to do that, security was a sine qua non condition. The Afghan forces are ready to assume that role now, which means that economic reconstruction will finally be able to start in the near future.