Democracy at home is the source of American power abroad

For much of the last century, the United States was admired as much for what it was at home as for what it did abroad. This combination was key to its eventual triumph over the Soviet Union. Today, however, the exceptionalism that won the Cold War has vanished. In its place is an America that has lost its way domestically and internationally. The two are intertwined. If the United States wants to regain its place in the world, it will have to look inward, for the problem lies there.

After World War II, the United States grabbed the mantle of global leadership to forge the iconic alliances and institutions that remain to this day: NATO, the United Nations, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and much more. It brimmed with confidence in its newfound mission, which was to lead what became known as the “free world” through the Cold War, with the expectation that victory would yield a new era of peace and prosperity.

America’s unrivaled power around the world had domestic roots—in its democratic institutions, dynamic economy, vibrant culture, and optimistic, future-oriented outlook. Its economy promised opportunity, its democracy rights and justice. Admittedly, none of these ideals were ever fully realized. But although the United States failed to achieve universal justice and opportunity, over the postwar decades it at least appeared to be moving in this direction.

For the rest of the world, the United States was the very symbol of modernity, an object of desire, fascination, and envy nearly everywhere. Cold War-era iconography—Hollywood, rock & roll, New York’s skyline, MTV, and Apollo 11, among many other icons—formed a key part of an almost irresistible American appeal, one that offered the world a more dynamic, prosperous, just, democratic, and humane future. That appeal was a universal one: what Americans enjoyed at home should be enjoyed by all abroad. This vision became a cornerstone of both the liberal international order as well as American global leadership.

For the rest of the world, the United States was the very symbol of modernity, an object of desire, fascination, and envy nearly everywhere.

The end of the Cold War and the heady 1990s that followed suggested an ultimate triumph. Tomes such as Francis Fukuyama’s The End of History and the Last Man, which asserted that liberal democracy had won a final, history-ending showdown of political systems, became hugely successful. Many believed that the United States, as the pinnacle of liberal democracy, would stand astride the world forever.

But, alas, this triumph proved to be only a mirage. The succeeding decades have exposed significant flaws in the great American experiment.

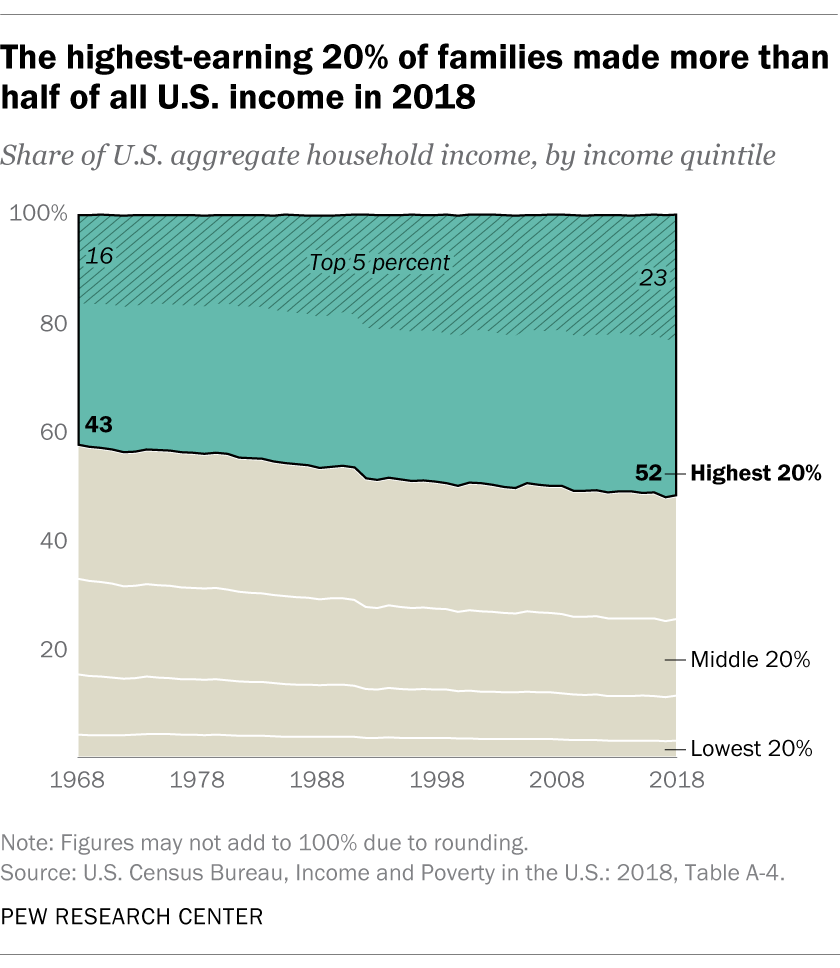

With stagnating wages, a lack of upward social mobility, and an inadequate safety net, the US economy has become known as much for its inequality as its vibrancy. Americans used to believe that their children could expect a higher standard of living than they had. For many people today, however, the American Dream more closely resembles a nightmare. Anti-elite sentiment, which flourished during and after the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent Great Recession, has become commonplace, the consequence of a system that appears to no longer reward the efforts of ordinary working people.

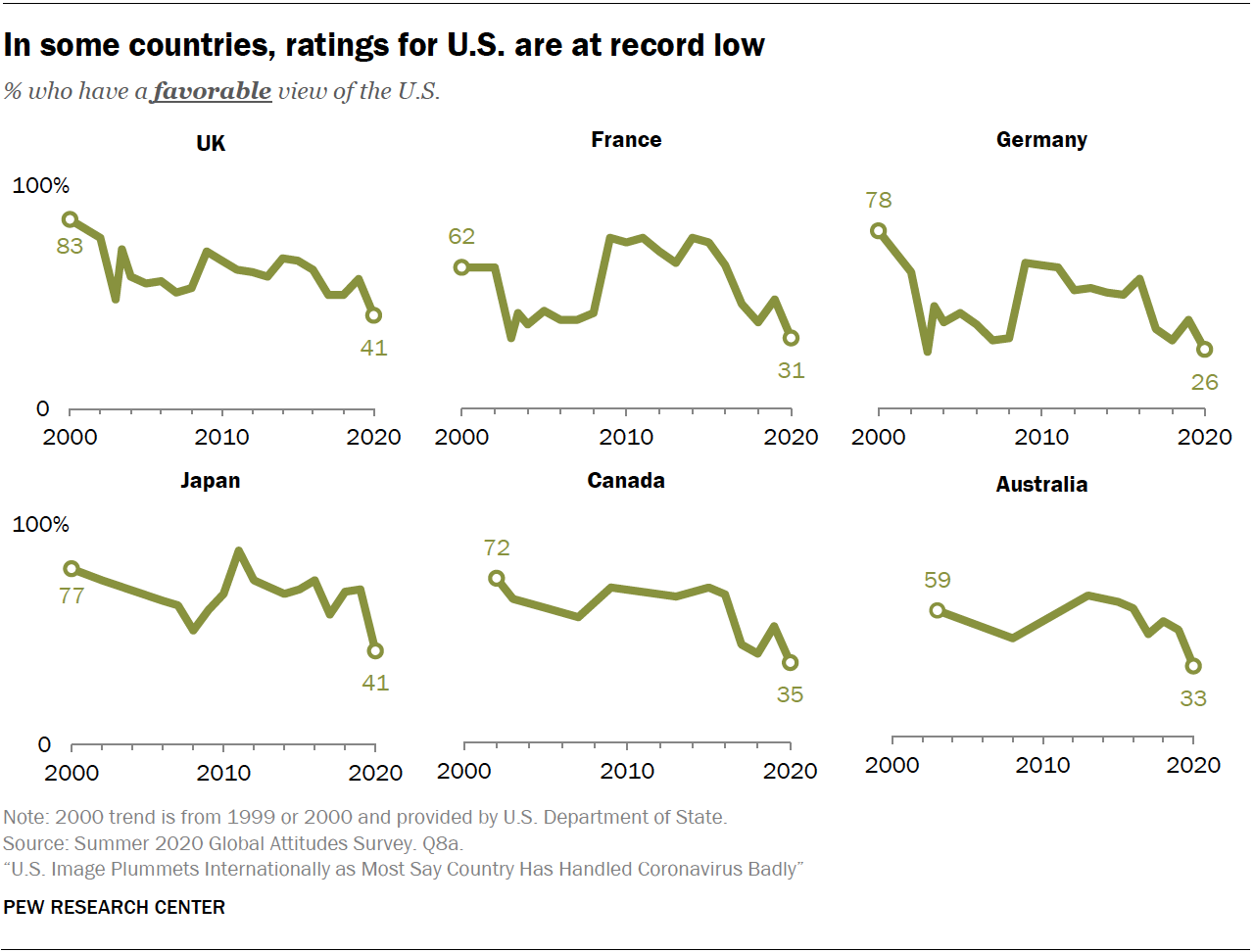

America’s relationship with the world has changed as well. Americans once imagined their country’s power to be limitless. Yet over the past decades, the United States has experienced a string of foreign-policy failures, in particular the “endless” wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. And in some key foreign-policy areas such as climate change, the U.S. more closely resembles a rogue state than a global leader. (The United States is the only country to withdraw from the Paris Agreement.) Americans rightfully can be forgiven if they doubt their country’s basic role as a positive and powerful force in world affairs, which was a cornerstone of the country’s self-identity during the Cold War. The rest of the world now certainly has its doubts: A September 2020 Pew Research Center survey of thirteen close U.S. allies found that “in several countries, the share of the public with a favorable view of the US is as low as it has been at any point” since Pew began polling on this topic in the early 2000s. A mere 9 percent of Belgians said they trusted U.S. President Donald Trump to do the right thing in world affairs.

Rising anger and frustration with these trends explain, at least in part, the erosion of Americans’ trust in public institutions and the democratic process, which have proved incapable of solving the nation’s growing list of problems. Widespread public grievances also help explain the 2016 election of Trump, a reality TV star who was singularly adept at taking advantage of this populist Zeitgeist.

Now, three decades after the End of History, only the bravest still speak of American exceptionalism. The United States leads the world in COVID-19 cases and deaths, with no end in sight. Although the unemployment rate has fallen from double digits, it remains stubbornly high, an indicator of the economy’s struggles in the face of a relentless pandemic that refuses to ebb. At the same time, the country is facing a very public reckoning with its own history of racial injustice. Added to all of this is a political system that appears weak rather than strong, paralyzed by hyper-partisanship and with a constitutional order now under severe distress.

For all of these reasons and more, the liberal international order that the United States built after 1945 is at considerable risk. There is a presumption that China, with an even more vibrant economy and (apparently) greater ability to rebound from COVID-19, will shape the future. The “American Century” appears to be over.

There is a presumption that China, with an even more vibrant economy and (apparently) greater ability to rebound from COVID-19, will shape the future.

But this rise-and-fall storyline is incomplete. There is an important difference between the United States and other great powers in history. As a liberal democracy, the country retains the capacity to rebuild and renew itself from within. The ability to course-correct in the face of adversity is democracy’s greatest strength. Unlike in authoritarian states, lasting change in a democracy does not require a government collapse, a coup, or a bloody revolution.

If the United States is to regain its lofty heights, Americans must take seriously a project of democratic restoration. The goal must be not only to reinvigorate the nation’s political architecture, so as to finally deliver on the country’s original promise to all of its citizens, but also to regain public trust in the problem-solving capacity of its democratic institutions. Both have taken massive hits over the past decades.

In a few days’ time, Americans will make a critical choice that will go some way toward determining the country’s future. But regardless of this particular election’s outcome, the United States will not be in a position to regain its previous global status unless citizens push their leaders, over the longer run, to return to the kind of good-faith and far-sighted policymaking that was the hallmark of American politics on its best days. Will Americans really strive to overcome the country’s various divides, to enable genuinely equal social and economic opportunity, to reduce its staggering levels of inequality, or to seriously address any of this century‘s multiple overlapping crises at home and abroad?

The United States does have the power to both right its own ship and fully employ its example to good effect around the world, but only if its citizens stay engaged in the hard work of democratic self-governance. Americans might have always disagreed with one another, but the United States has been strongest when that struggle pointed toward a more perfect union—toward the ideal that is promised in its Constitution. A return to this model will show once again that the United States can lead at home and abroad, not through force but through moral example.

Peter Engelke is a deputy director and senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center on Strategy and Security.

Julian Mueller-Kaler is a resident fellow at the GeoTech Center and also researches global trends in the Scowcroft Center’s Foresight, Strategy, and Risks Initiative.

Further reading:

Image: The United States Capitol is pictured among U.S. flags during sunset in Washington, U.S. October 22, 2020. REUTERS/Hannah McKay