The legacy Brent Scowcroft leaves behind

With Brent Scowcroft’s passing on August 6 at age ninety-five, the United States lost one of the central players in the transatlantic community’s success in bringing a peaceful end to the half-century-long Cold War with the Soviet Union, in the remaking of the European map to include a reunified Germany, and in providing the opportunity for the spread of democracy and freedom to Central and Eastern Europe.

His death marks the end of an era and the loss of a foreign policy icon of historic accomplishment, unshakeable integrity, and consistency of purpose, illustrated by the rich story of his life below.

Seldom has such great accomplishment been accompanied with such remarkable modesty. Just as General Scowcroft never sought credit for his role in the Cold War’s end, he also quietly acted as adviser to six American presidents without any greater desire than to serve his country.

The same was true at the Atlantic Council, which he stepped in to save and reshape. He founded its Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security in 2012 because it was the right way to ensure the transatlantic community’s primacy, humbly consenting to provide his name for the center only after others convinced him that it would better ensure its success.

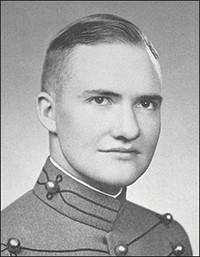

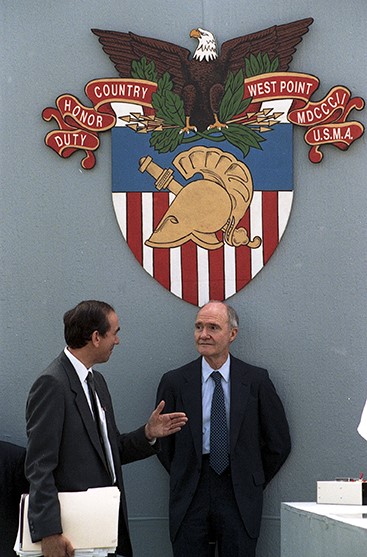

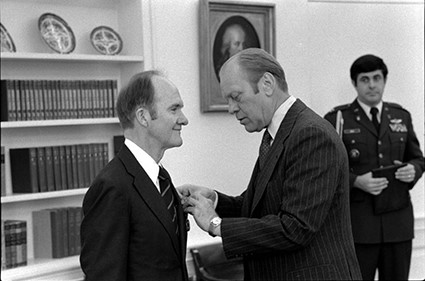

Scowcroft devoted his life to public service and national security—from his career as a young West Point cadet during World War II, to his service as the only man ever to have served twice as national security advisor, for Presidents Gerald R. Ford and George H.W. Bush.

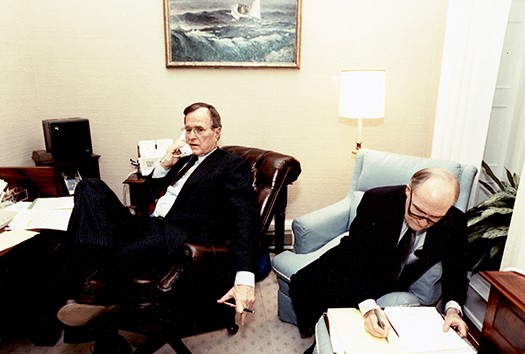

Presidential scholars will remember him for shaping and defining the role of the national security advisor. To this day, new national security advisors turn to his model of foreign policy stewardship during the Bush presidency from 1989 to 1993 as the most effective national security process since the position was introduced by President Eisenhower in 1953.

Yet to truly understand the Scowcroft legacy, one needs to reach beyond the final months of the Cold War to a lifetime characterized most of all by the quality he considered most significant in any leader: judgment. Add to that huge doses of integrity, managerial skill, decency toward others, and an intellectual rigor that was deployed with strategic purpose.

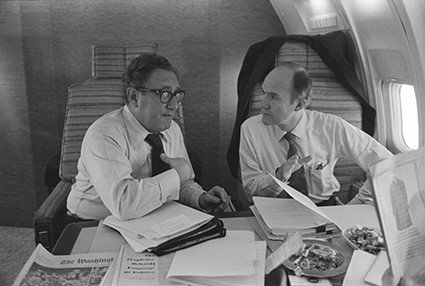

He is considered one of the three great foreign policy practitioners of his time, alongside Henry Kissinger, age ninety-seven, and Zbigniew Brzezinski, who passed away in 2017 at age eighty-nine. His lasting mark won’t only be in the history he shaped but also in the countless individuals he mentored.

This is his story.

A defining moment

The battleground was a familiar one to Lt. Gen. Brent Scowcroft: the White House Cabinet Room where President George H.W. Bush had convened his National Security Council to reach urgent decisions amid an unfolding crisis. It was 8 a.m. on August 2, 1990, only thirteen hours since Saddam Hussein had sent his Iraqi army into Kuwait and less than ten months after the Berlin Wall’s fall had signaled the West’s Cold War victory.

Yet Scowcroft, Bush’s national security advisor, already sensed what he considered a dangerous “air of resignation” among the men in the room that the United States would simply have to accept the Iraqi occupation of oil-rich Kuwait. Bush himself had set the tone just minutes before the meeting when he told reporters outside that he wasn’t contemplating military action—though Scowcroft’s instincts told him nothing short of armed force would reverse Saddam’s aggression. With the information still fresh and the participants stunned by events and weary from a long night of crisis management, the meeting focused on options to punish Iraq and deal with the consequences of its invasion, and not what the United States and the international community could do to restore Kuwait’s sovereignty. Participants in the meeting remember a disorganized discussion ill-suited to the gravity of the occasion. “To call it unfocused would be charitable,” recalled former National Security Council (NSC) staffer and current Council on Foreign Relations President Richard Haass.

Scowcroft left the meeting ill at ease with its outcomes and concerned at the seeming lack of appreciation of the significance of the invasion to the interests of the United States. For Scowcroft, the invasion violated the broad international principles the United States hoped would define an emerging post-Cold War order. It was a uniquely malleable period of history, those rare occasions when norms are tested and standards set. The Soviet Union had not yet collapsed, but the Warsaw Pact was imploding, and Moscow and Washington were no longer the bitter enemies they had been for most of the period since World War II. Scowcroft regarded Saddam’s invasion as the first test of a new era’s possibilities and the pattern of global behavior one needed to establish. “Aggression—simple, naked aggression—ought not to be allowed as part of this new world order,” he would later reflect.

Shortly after the meeting, Scowcroft would express his misgivings to the president and what he saw as the enormous stakes of what was unfolding in the Gulf. He would find a receptive audience in his close friend and intellectual soul mate, George H.W. Bush. Bush, a decorated World War II fighter pilot, was the last of a series of US presidents who would come of age during the war and would be defined intellectually by the lessons from the West’s appeasement of Adolf Hitler’s aggression at Munich in 1938. The president would offer to open the next NSC meeting with a description of the importance of events to the United States and of the need for a stronger set of options. The seasoned Scowcroft, aware of how presidential interventions can stifle debate, suggested instead that he open the meeting and that the president make his judgments based on the ensuing discussion.

Bush agreed and at the next NSC meeting Scowcroft strongly and forcefully made the case that Saddam’s aggression was of paramount importance to US interests and that it must be met with a direct and strong response. At the conclusion of his intervention, Deputy Secretary of State Lawrence Eagleburger pounded the table and proclaimed, “Absolutely right!” The discussion that followed Scowcroft’s intervention took on a more practical nature and put the president’s team in the proper frame of mind for a meeting the next day at Camp David, where military options would be debated for the first time.

History would record the Gulf War that would follow shortly thereafter, known better at the time as Operation Desert Storm, as a rare moment of global common purpose. Under an unprecedented United Nations Security Council mandate, Washington would lead a diverse coalition of thirty-nine nations in a rapid and devastatingly effective military campaign to reverse Iraq’s invasion and annexation of Kuwait. How the Bush administration’s decisions unfolded and the strategy the administration adopted in prosecuting the war provides insights into Scowcroft’s unique and multifaceted approach to protecting the United States’ international interests.

A soldier-scholar

Scowcroft came to the Bush administration as a soldier-scholar whose crucible was the aftermath of World War II, when the US government sought to develop its best military minds to navigate its new superpower status in a dangerous nuclear world. At the time of the Gulf War, he already was the most experienced national security advisor since President Dwight D. Eisenhower invented the job in 1953. He was and still remains the only man to have ever served two presidents as national security advisor—three when one considers his de facto responsibilities as Henry Kissinger’s deputy national security advisor when Kissinger served both as secretary of state and national security advisor. Given his role as adviser to US presidents since then and through President Barack Obama, no individual has provided as many commanders-in-chief as much national security advice—irrespective of party lines.

Yet in framing a response to the Iraqi invasion, Scowcroft knew the United States was facing a unique moment of immediate danger and historic possibility. With his doctorate and masters in political science from Columbia University, and training in Russian and Serbo-Croatian at Georgetown University, Scowcroft had become an adherent of the “realist” school of foreign policy that one could trace from George Washington’s farewell address through to Hans Morgenthau. For realists such as Scowcroft, the world exists in a natural state of competition and disorder, and for the United States to intervene militarily in sorting out that disorder, a very high bar of strategic self-interest would have to be proven.

Scowcroft’s particular worldview was a derivative of the realist philosophy, which he referred to as “enlightened realism.” An enlightened realist, Scowcroft saw the world as existing in a natural state of disorder, but recognized the essential—if not limitless—role US power and leadership can play in making the world a more orderly and safe place. Yet this view was tempered with an awareness that historical forces, geography, and culture impose limits on the transformative impact of US power. From such a worldview flows an important belief in the necessity of allies and coalition partners to share the burden, and a sense of judgment about when and how US power can best advance its interests and values. Scowcroft believed “we need to look out at the idealistic goal, but keep our feet on the ground, and say ‘what kind of steps can we take that are realistic?’”

Bush and Scowcroft would adopt just such an approach as they devised their strategy for rolling back Saddam’s invasion of Kuwait. The two men would craft their vision for the conflict to come during a four-hour conversation on a fishing boat off the coast of Walker’s Point, Maine, on August 23, 1990. It was the first chance Bush and Scowcroft would have to engage in a philosophical and strategic discussion about their vision for the emerging post-Cold War era. “Our conversation that day broadened to ruminations about being sure we handled the crisis in a way which reflected the nature of the transformed world we would face in the future. We were both struck with the thought that we were perhaps at a watershed in history. The Soviet Union was standing alongside us, not only in the United Nations, but also in condemning and taking action against Iraqi aggression. That cooperation represented fundamental change,” Scowcroft recalled.

During that conversation, Scowcroft would coin the term “new world order,” which Bush would use to define his vision of a more collaborative post-Cold War era. Foreign policy expert David Rothkopf describes the Bush administration’s approach to confronting Iraq as wisely following in the footsteps of the founding Atlanticists who built the post-World War II order. “They followed in the tradition of the vision for America and its role in the world that had been established by Truman, Marshall, Acheson, and their colleagues in the days after the Second World War, looking outward, investing in institutions, and building support for what the United States could do on its own—but doesn’t have to—around the world,” Rothkopf said.

But even as Bush and Scowcroft sought to prosecute a strategy in the context of a “new world order” they took care to ensure that they could end the conflict having successfully achieved US and allied objectives. Scowcroft was convinced that once Iraqi troops had been forced out of Kuwait, the US military should not march on to Baghdad to unseat Saddam. He told Bush that although the military would have had little trouble achieving its initial mission, a US occupation of Iraq would lack the international support of the Kuwait operation—and would have been politically and militarily untenable. Years after the war, Scowcroft would reflect on the administration’s limited war objectives, which would come under growing criticism from conservative voices in the latter half of the 1990s, saying, “It was never our objective to get Saddam Hussein. Indeed, had we tried we still might be occupying Baghdad. That would have turned a great success into a very messy, probable defeat.”

It was with that warning in mind that Scowcroft famously opposed a second Iraq war by a second Bush some eleven years later, writing a prescient op-ed in the Wall Street Journal on August 15, 2002, opposing a US military campaign to unseat Saddam. In the piece, Scowcroft would warn of the high risks of a large-scale military occupation of Iraq and of its potential to distract from the strategic priority of fighting terrorism. “An attack on Iraq at this time would seriously jeopardize, if not destroy, the global counter-terrorist campaign we have undertaken. The United States could certainly defeat the Iraqi military and destroy Saddam’s regime. But it would not be a cakewalk. On the contrary, it undoubtedly would be very expensive—with serious consequences for the US and global economy—and could as well be bloody,” he wrote.

Scowcroft has both shaped his times—and has been shaped by them.

His extraordinary life began in prosaic fashion with his birth on March 19, 1925, in Ogden, Utah, to Lucille and James Scowcroft, a prosperous wholesale grocer. It was the year that Benito Mussolini took dictatorial powers over Italy, when Hitler published his personal manifesto Mein Kampf, and when newly elected Calvin Coolidge became the first president whose inaugural was broadcast on radio. Also born that year were Pol Pot, Margaret Thatcher, and Robert Kennedy.

Unlike the two other great strategic thinkers who have been national security advisors during his time—the German-born Henry Kissinger and the Polish-born Zbigniew Brzezinski—Scowcroft’s crucible was the American heartland between World Wars I and II, where he was reared as a Mormon child through the Great Depression and from age 12 dreamed of attending West Point. Education was a point of emphasis and pride for the Scowcroft family, in part because Scowcroft’s father never graduated high school and put a premium on his son’s ability to obtain the education that he was never able to receive. Scowcroft enrolled in West Point in the midst of World War II, expecting to go to war upon graduation. Instead, he found himself in the midst of his training for combat just as the war was coming to a close in 1945.

Two years later, on June 5, 1947, cadet Brent Scowcroft graduated in the top quarter of the 310 members of the 151st class of the United States Military Academy. Former Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in World War II and then Chief of the Army Staff Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower addressed the class of 1947 at West Point telling them, “Obligation to yourself and your nation demands that your talents be developed to the full… War is mankind’s most tragic and stupid folly; to seek or advise its deliberate provocation is a black crime against all men. Though you follow the trade of the warrior, you do so in the spirit of Washington—not of Genghis Khan. For Americans, only threat to our way of life justifies resort to conflict; but once engaged in such defense, the country will look to you for the skill, the heart and the brain to lead her surely to victory.”

Two days later, just two hundred miles to the northeast, Secretary of State and former World War II Chief of the Army Staff George C. Marshall would deliver one of the most important commencement addresses in history at Harvard College. He would outline the Truman administration’s European Recovery Plan, which would come to be known as the Marshall Plan. “An essential part of any successful action on the part of the United States is an understanding on the part of the people of America of the character of the problem and the remedies to be applied. Political passion and prejudice should have no part. With foresight, and a willingness on the part of our people to face up to the vast responsibility which history has clearly placed upon our country, the difficulties I have outlined can and will be overcome,” he said.

Just as the effects of the Marshall Plan were taking hold in Europe, the United States would make its formal commitment to Europe’s security by joining the North Atlantic Treaty Organization on April 4, 1949. Eisenhower would be NATO’s first supreme commander—creating the most unique alliance in world history through the establishment of an integrated military command among the United States and former European rival powers. The optimistic hope for a more collaborative world order expressed in the closing days of World War II began to take a much darker turn with the descent of the Iron Curtain in Central Europe, the victory of the Communists in China’s civil war in 1949, and the North Korean invasion of South Korea in the summer of 1950. In response to these challenges and the threat they posed to Europe’s fragile peace, prosperity, and freedom, visionary American statesmen like Truman, Marshall, Eisenhower, and Acheson would forge the political, economic, and security ties across the Atlantic that have formed the cornerstone of US foreign policy ever after.

Those dramatic events would provide the heady backdrop for the early days of Scowcroft’s military career as he began pilot training in the Army Air Corps. His career would forever change when the engine in his P-51 Mustang malfunctioned during a dogfighting exercise over the New Hampshire woods in January 1949, breaking his back and leaving him in a full-body cast. Complications kept him in military hospitals for two years. The doctors told Scowcroft he would never fly again. Recalled Scowcroft on this career-changing and life-altering experience, “When you suddenly can’t do what you thought you were destined to do, you simply have to find something else to do.”

The military easily found a new role for the gifted Air Force officer who could no longer fly. The emerging United States Air Force, created as its own separate service only in 1947, needed strategic thinkers capable of navigating the challenges of a world forever changed by the emergence of deadly nuclear weapons and the vast advances and innovations to air power made during World War II. The Air Force recognized Scowcroft’s intellectual ability and invested in his education. He would become one of the early breed of post-World War II soldier-scholars who would come to play a growing role in shaping military affairs throughout the Cold War and until more recent times.

Scowcroft gained his MA and PhD in political science from Columbia University, and was trained in Russian and Serbo-Croatian languages at Georgetown. The Air Force would send him to Belgrade to serve as the assistant Air Force attaché in 1959. He served under US Ambassador George Kennan, the author of the United States’ containment strategy against the Soviet Union. Scowcroft would be one of a first generation of Cold War defense intellectuals who would study the confrontation with Moscow on its own terms—not as an extrapolation of World War II. In addition to later serving as the interim chair of the Political Science Department at the Air Force Academy, Scowcroft would rise through the ranks of the US Air Force through a series of strategy, staff, and long-range planning positions in the Pentagon.

Scowcroft’s first job at the White House came at age 45 in the Nixon administration, where he served as the president’s military aide, advancing his trips and accompanying Nixon on his historic visits to China and the Soviet Union in 1972. Impressed by Scowcroft’s willingness to stand up to H.R. Haldeman at the height of his powers as Nixon’s chief of staff, and (Scowcroft believed) because Kissinger reckoned the Mormon-raised military man would be loyal to him, Kissinger chose Scowcroft as his deputy at the National Security Council. In 1975, Kissinger convinced President Gerald R. Ford to promote then Lt. Gen. Scowcroft to succeed him as national security advisor when Kissinger moved to the State Department.

Scowcroft was profoundly influenced by Kissinger, learning from him “what it is like to have a really strategic mind.” But Scowcroft also understood that despite Kissinger’s abilities and stature, Ford would need an independent national security advisor who would ensure a collaborative national security policy and provide additional options and ideas to the president. Ford NSC staffer Jonathan Howe recalled in Rothkopf’s book Running the World, “[W]hen Brent took over, it was incumbent on him to ensure that there had been a real split, that he was his own man. He and Kissinger were still close and good collaborators, but Brent knew the boss was President Ford.”

After leaving government at the conclusion of the Ford administration, Scowcroft would remain at the forefront of the national security debate throughout the Carter and Reagan presidencies. His expertise on arms control and strategic weapons would lead President Ronald Reagan to make him chair of the President’s Commission on Strategic Forces, popularly known as the “Scowcroft Commission,” in 1983. The Commission would recommend the deployment of “a force of small, single-warhead ICBMs” to ensure greater survivability in the event of a first attack and thereby “greatly enhance deterrence of nuclear attack and support NATO’s strategy of Flexible Response.”

Reagan would again rely on Scowcroft’s thought leadership and unshakeable integrity by nominating him to the Tower Commission in the aftermath of the Iran-Contra affair. The Commission investigated the causes of Iran-Contra and offered suggestions for the reform and improved functioning of the National Security Council.

Scowcroft would not have to wait long for the opportunity to put these ideas and recommendations into practice. President-elect Bush, perhaps the best-prepared president in history to handle foreign policy, would select a deeply experienced national security team and pick Scowcroft to return to the White House to manage the foreign policy process and serve as his closest adviser. He sought a strong national security advisor who could serve as an honest broker and able manager of competing views and opinions from his strong-willed Cabinet members. “He would not try to run over the head of Cabinet members, or cut them off from contact with the president, yet I also knew he would give me his own experienced views on whatever problem might arise,” Bush recalled of his selection of Scowcroft.

A significant change in relations between the West and the Soviet Union was afoot when Bush took the oath of office in January 1989, but neither he nor Scowcroft could have foreseen the dramatic political transformation that would sweep the world during their four years in office. The entire bipolar world order that had existed since the end of World War II would come crashing down, starting with the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989 and concluding with the descent of the Soviet flag over the Kremlin on Christmas Day, 1991. The excitement of the era would unleash tremendous possibilities, but also grave dangers.

Despite the relaxed East-West tensions when Bush took office, Scowcroft rejected the idea that some were putting forward that the Cold War was over. “I and the president felt that it was not over because the heart of the Cold War really was the division of Europe. And Soviet troops were still everywhere in Eastern Europe,” he said in a 2009 interview with Atlantic Council President and Chief Executive Officer Frederick Kempe. The administration set out the goal of removing Soviet troops and influence from Central and Eastern Europe without panicking Moscow into inciting crackdowns similar to those in Berlin in 1953, Hungary in 1956, or Czechoslovakia in 1968. It was a delicate task requiring statesmanship, diplomacy, and wisdom.

The fall of the Berlin Wall

The greatest test of all would come with the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989 and the pressures it would unleash within Germany for eventual reunification. As the world celebrated the end of a divided Germany, Bush faced pressures from Congress and the media to claim victory in the Cold War and gloat over a triumph for freedom. The president and Scowcroft knew that public triumphalism at such a period of transformation could unleash reactionary forces in the Soviet Union and undermine their long-term strategy of rolling back Soviet influence elsewhere in Europe. “The worst thing, we thought, would be for the president to gloat that we’d won, because what we wanted was for this momentum to keep going,” recalled Scowcroft years later.

The momentum would continue even faster than Scowcroft and Bush expected. The issue of German reunification and Germany’s eventual membership in NATO would pose difficult questions not only for Moscow, but also allies in Paris, London, and elsewhere. Consultation and collaboration would be the order of the day for the White House as the United States would work with its allies to undertake reforms of the NATO alliance to orient it toward post-Cold War aims and consult with France, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to bring about the peaceful reunification of Germany within a reformed NATO alliance. It was a stunning triumph of diplomacy, made possible through important personal ties Bush, Scowcroft, and Secretary of State James A. Baker III had forged with their counterparts over years of sustained engagement. Scowcroft recalled this era as an historic achievement and contrasted it to previous examples where history failed to resolve the complicated “German question” in a peaceful fashion. “This was personal diplomacy in the finest sense of the term. Coalition-building, consensus, understanding, tolerance, and compromise had forged a new Europe, transformed and united. There was no Versailles, no residual bitterness,” Bush and Scowcroft wrote in A World Transformed.

Analysts view the White House’s management of this tumultuous period of history with admiration. “In the recent history of US foreign policy,” wrote Rothkopf, “there has been no president, nor any president’s team, who, when confronted with profound international change and challenges, responded with such a thoughtful and well-managed foreign policy.” Rothkopf called the Bush administration and Scowcroft’s foreign policy stewardship “a bridge over one of the great fault lines of history (that) ushered in a ‘new world order’ it described with great skill and professionalism.”

If Scowcroft’s handling of Desert Storm showed one of the United States’ premier national security thinkers at the height of his powers—putting together the pieces of crisis response in its larger, global, historical context—the Bush administration’s steady handling of German unification and the collapse of the Soviet empire more largely demonstrated how history is often made not through single, dramatic actions but rather through wise, principled, and consistent leadership.

Historians, however, are unlikely to capture adequately perhaps the most unique aspect of Scowcroft’s legacy. Namely, his life has been a consistent demonstration that foreign policy leadership must be as much about successful mentoring, management, and execution as it is about properly applied intellect, strategy, and understanding of history. It has been his unique combination of all of these elements that has set him apart from all his peers. The most brilliantly conceived US international strategy will fall short if those who frame it fail to manage the complex inter-agency operations of the US foreign policy apparatus, fail to forge and maintain international alliances or fail to mentor and nurture a new generation of US foreign policy actors.

In the New Republic in February 1992, John Judis put it this way, “The unflappable, intelligent, loyal Scowcroft has succeeded where almost every other recent National Security Advisor has failed: he has managed both to be a highly influential adviser to the president and to coordinate effectively the debate among the president’s top foreign policy officials. Scowcroft has been able to combine these two functions because he lacks the insatiable drive toward power and fame that has crippled previous National Security Council heads. In a town corrupted by the compulsive pursuit of celebrity, Scowcroft is the rare and stunning exception.” Asked to judge Scowcroft’s most useful qualities as National Security Advisor, Bush said, “Brent has a great propensity for friendship. By that, I mean (he is) someone I can depend on to tell me what I need to know and not just what I want to hear, and at the same time he is someone on whom I know I can always rely on and trust implicitly.” What Bush particularly valued was that Scowcroft “was very good about making sure we did not simply consider the ‘best case,’ but instead considered what it would mean if things went our way, and also if they did not.”

What sets apart Scowcroft’s legacy is that it is not just about a worldview, which he had, but also about a way of operating in the world, which has been just as important to his success. His thinking was guided by key principles, including the importance of history in shaping international affairs, the necessity of strong US international leadership to ensure that a world of natural disorder does not become chaos, the importance of gaining domestic and international support for US leadership, and the utility of working through allies, coalitions, and international institutions. Despite his military background, Scowcroft held the belief that although military force is an important tool of statecraft, it is not a substitute for policy, and he maintained the necessity of always taking the long view when deciding policies of where the United States wants to be two decades from now—and not just immediately.

The strategist

Yet the Scowcroft leadership approach dictated that a successful foreign policy has to be about more than ideas. It must also be about their successful execution, and that is perhaps where Scowcroft as a strategist excelled most. He consistently promoted free and open debate to arrive at the best conclusions. He was a fierce, but always civil, advocate of the directions he considered the right approach, whether it was his willingness to disagree with Haldeman in the Nixon days or his open criticism of George W. Bush’s Iraq War strategy—though it would result in his estrangement from the White House and formerly close personal friends serving within the administration.

Throughout Scowcroft’s years of service in government and in his years as a private citizen and elder statesman, he put a premium on selecting, developing, and empowering the best talent for his team. Among Scowcroft’s golden rules was to “surround yourself with people smarter than you.” His list of protégés included some of the most prominent and well-known names in national security such as former Secretaries of Defense Robert Gates and Ash Carter; former National Security Advisors Stephen Hadley, Condoleezza Rice, and James L. Jones, Jr.; Council on Foreign Relations President Richard Haass; former Secretary of the Treasury Timothy Geithner, and countless others.

Scowcroft would use his skilled team in innovative ways to ensure the best outcomes and maximize his talent. As National Security Advisor, he formed what came to be known as the “ungroup,” led by NSC defense expert Arnold Kanter, to offer innovative thinking on arms control with the Soviet Union through its unorthodox structure of bureaucratic leadership that put the focus on solving problems instead of protecting institutional interests. Scowcroft also created principles and deputies’ committees within the NSC that are still in existence today because of their effectiveness in producing important foreign policy decisions while protecting the president’s valuable time. He focused on results and never sought glory, thus always keeping the confidence of his constituents while forming exceptionally close, trusting, and confidential relationships with Ford and Bush Sr. He deflected the credit and let others be the stars.

Scowcroft continued to shape foreign and national security policy in the nearly quarter century since the George H.W. Bush administration concluded. Well into his 80s, he was frequently called on to testify before Congress, chair high-level government and academic committees, and provide counsel to presidents, Cabinet secretaries, members of Congress, leadership of the armed forces, and foreign leaders.

One of his greatest contributions outside of government was to cultivate institutions capable of fostering an informed, bipartisan discussion on the major strategic challenges facing the United States and its allies. One of his most significant achievements was to revive and rejuvenate the Atlantic Council, where he served as a board member since the 1970s up until his death.

Scowcroft saw the Atlantic Council as a uniquely valuable institution given its long history of bipartisanship and legacy of incorporating allied and partner perspectives into the foreign policy debate. In the mid 2000s—just after the bitter transatlantic debate about the Iraq war—he challenged the institution and its new leadership to restore the Council’s traditional relevance and stature, while updating its Atlanticist mission for a world where new partners would be needed to solve global challenges. His leadership of the Council was transformational.

Scowcroft invested his own standing and reputation into the revitalization of the Atlantic Council. Those of us who worked on the Council staff in those sometimes perilous days for the organization took courage and inspiration from knowing that Brent Scowcroft was fully invested in our success. Scowcroft frequently made significant financial contributions to support the Council and invested his time and reputation to recruit Kempe to take on the CEO job in 2006 and Jones to serve as chairman in 2007, when the organization was finding new footing.

In 2012, the Atlantic Council established a Brent Scowcroft Center on International Security as a means of recognizing Scowcroft’s contributions to national security and to Atlantic Council history. The Council’s goal in founding the Center was to embody and institutionalize Scowcroft’s legacy of bipartisanship, strategic thinking, commitment to US leadership of alliances and multilateral institutions, and mentorship of future generations.

Scowcroft again returned to a leadership position at the Atlantic Council, serving as interim chairman upon the nomination of Chuck Hagel to serve as Secretary of Defense in 2013. He recruited fellow Utah native and former governor, Jon M. Huntsman, Jr., to relieve him as Council chairman, capping a legacy of nearly forty years of service to the organization.

Scowcroft’s passing leaves a void in the Atlantic Council and in the broader national security policy community. It comes at yet another transitional moment in history, the likes of which marked the defining moments of his career.

Scowcroft began his long career in national security during the concluding days of World War II and the dawn of the Cold War. He played a key role in crafting national security policy through the height of the Cold War and helped to forge a “new world order” with Bush in its aftermath. As a retired statesman, he shaped the conversation about how the United States should navigate the unipolar moment and the emergent challenges of the war on terrorism.

The world order that Marshall and Eisenhower helped forge after World War II—and which Scowcroft and Bush renewed at the end of the Cold War—is at risk. The United States is flirting with isolationism, nationalism, and retreat from the world stage. Russia, China, Iran, and others challenge not only US power, but the concept of individual freedoms and an international system based on the rule of law. The United States and its European allies once again question the commitment of one another to their collective defense. New technologies are quickly reshaping geopolitics, national politics, and the right of individuals.

We can no longer rely on Scowcroft’s wisdom to help guide us through these transformational times. Yet we can draw upon his legacy and the lessons learned from his more than half century of public service to help navigate the challenges of the future.

Scowcroft’s views evolved with the changing times, but his core convictions remained. He believed in the importance of strong US relationships with allies in partners in the Cold War, just as he did at the height of the unipolar moment. He looked to the national interest as the founding principle of US foreign policy throughout his many years in public policy. He firmly believed that active US leadership on the world stage was the best recipe for a more safe and free world. And he instinctively understood that developing and cultivating future generations of principled national security leaders would be required for the United States to sustain its leading role in world affairs.

As our country navigates yet another transformational moment in geopolitics, Scowcroft’s guiding principles remain a relevant blueprint for future generations to follow. As a tribute to a man who has done so much for our country and its allies, the Atlantic Council honors his legacy through the ongoing work of the now renamed Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security and by fighting for the enduring values that he embodied throughout the course of his rich life.

Frederick Kempe is president and CEO of the Atlantic Council.

Jeff Lightfoot is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security.