Ukraine air war examined: A glimpse at the future of air warfare

Early on the morning of February 24, 2022, Russian forces streamed over the Russian and Belorussian border into Ukraine, initiating a large-scale invasion. Predictions in the West were dire; Russian forces could take the Ukrainian capital of Kyiv within days, perhaps forcing a Ukrainian capitulation in less than a week. Those predictions proved wildly off-base. Ukrainian forces fought bravely and effectively; Russia failed to establish air superiority, capture Kyiv, or take any major cities in northern Ukraine; and the Donbas campaign is locked in a virtual stalemate. Despite estimates that Russia would establish air superiority within seventy-two hours, Russian forces have failed to control the skies, and have suffered huge aircraft losses that have hindered their air support for the ground invasion.

This paper will examine the first six months of the air war, focusing on three main areas. First, it will evaluate both Ukrainian success and Russian failures, deriving initial lessons learned from the air campaign. Second, the paper will describe the changing character of air and space warfare—how a democratization of air, space, and intelligence capabilities via commercial and dual-use assets will allow adversaries to contest air and space control. Finally, the paper will provide actionable recommendations for the air and space forces of the United States and its allies and partners, to help ensure they are prepared to dominate air and space campaigns in the future.

Learning lessons from Russian failures and Ukrainian successes

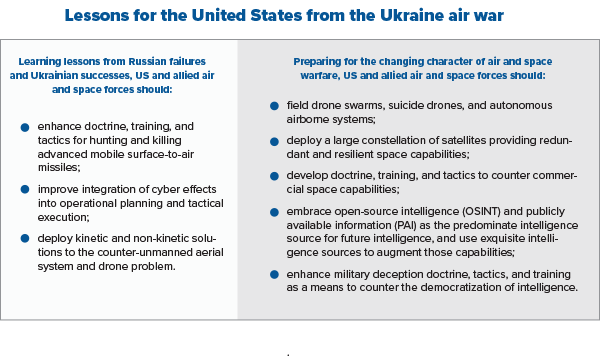

The United States and its allies and partners need to be sure they do not dismiss the Ukraine air war simply as an example of Russian ineptitude, but instead examine Ukrainian successes and Russian tactical improvements over the course of the war and modify their warfighting concepts, doctrine, tactics, and training. Russia deployed an impressive air and air-defense force to the region prior to the invasion, including hundreds of advanced fighters, fighter-bombers, and attack aircraft, as well as modern short-, medium-, and long-range surface-to-air missiles (SAMs). Russia also employed long-range aviation bombers launching cruise missiles, and special mission aircraft designed to provide airborne command and control (C2) and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR). Ukraine countered this impressive fleet with a small and aging force of fourth-generation fighters, and legacy but capable short- and medium-range SAMs. On paper, Russia held clear quantitative and qualitative advantages over the Ukraine Air Force.

Despite Russia’s clear advantages in both force size and capability, Russian forces failed to establish air superiority for a multitude of reasons. First, their initial strikes on February 24 were largely ineffective in landing an immediate knockout blow. The air and missile strikes were distributed across the country, preventing the concentration of effects, and those effects were not targeted against critical C2 nodes. Consequently, Ukrainian air and air-defense capabilities were not prohibited from conducting defensive operations. Second, Russia’s non-kinetic effects had limited impact and were poorly integrated with the kinetic strikes. Cyberattacks and electronic warfare, including counter-space attacks, were observed in the initial offensive, but their effects were severely limited. Third, Russia’s suppression of enemy air defenses (SEAD) plan was wholly inadequate. Russian air and missile strikes did not effectively target Ukraine’s integrated air-defense system (IADS). They failed to destroy mobile SAMs, and their targeting of Ukrainian military airfields was largely ineffective, as they did not crater runways nor destroy nearly enough combat aircraft on the ground to prevent effective Ukrainian defense. Fourth, Russian forces failed to integrate tactical or battlefield intelligence; they did not appear to know where high-value targets were, including Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, mobile SAMs, critical IADS nodes, and Ukrainian military command posts. Finally, Russia appeared to have no plan for countering Ukrainian uncrewed aerial systems (UASs) and drones, and those systems took a devastating toll on Russian ground forces. The air campaign appeared to have no overarching concept or unifying theme: Russian forces were unable to decapitate Ukrainian leadership, or blind and/or paralyze Ukrainian IADS. As such, Ukrainian air defenses were operating at or near full capability, and they were able to institute huge aircraft losses from the first day of the conflict.

The United States and its coalition partners have proven their ability to execute a devastating air campaign over the last thirty years, and to avoid many of the mistakes Russia has made. There are areas, however, in which the United States can and should learn from Ukraine’s heroic defense and Russia’s historically inept performance. First, the United States needs to put special focus on the finding and destroying of mobile air-defense systems. Ukraine’s mobile SAMs have moved frequently, and Russia has failed to eliminate them from the battlefield, even six months into the conflict. This subset of SEAD, finding and killing mobile SAMs—especially those with advanced, long-range capability—must be a focus of airpower doctrine, tactics, and training for the United States and its allies and partners. Second, even the United States and its closest allies have struggled to adequately integrate cyber effects into operational planning and tactical execution, instead keeping those capabilities as strategic or national-level weapons. The United States and its allies must overcome security hurdles and find a way to bring cyber effects to the warfighter—in this case, integrated into a tactical air campaign. Third, the United States and its allies and partners must examine the counter-UAS mission that will be discussed extensively below, and develop unique weapons, doctrine, tactics, and training tailored specifically to defeating small UASs and drones.

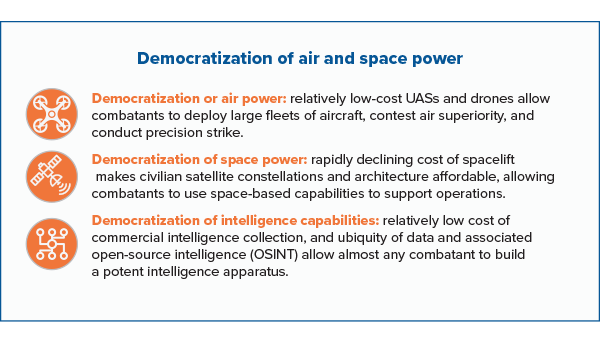

Preparing for the changing character of air and space warfare

Although the primary mission of air and space forces remains the same—to gain control of the skies and space, or air and space superiority—the character of air and space warfare is rapidly evolving. The primary driver of this change is the democratization of airpower and spacepower that will allow many nations to field potent air and space capabilities, potentially countering a numerically superior force in those domains. The barriers to fielding potent air, space, and intelligence capabilities are decreasing rapidly, and many nations—or even non-state entities—can procure and deploy large fleets of small, low-cost, expendable UASs and drones, making establishing air control extremely difficult and costly. Similarly, the space domain can also be contested through the use of commercial space assets and functions, which are rapidly becoming more affordable. Finally, robust intelligence capabilities can be developed with little investment in exquisite collection capabilities, instead relying on commercial imagery and open-source intelligence. A savvy adversary can contest air and space superiority via a thoughtful investment in critical air, space, and intelligence assets and capabilities.

The democratization of airpower

Air superiority is likely to be more difficult to achieve in future conflicts than in the counterterrorism and counterinsurgency fights of the early twenty-first century for two major reasons. First, the proliferation of mobile, advanced SAMs will increase the risk to air forces seeking to establish air control. The second reason, which will be the focus of this section, is the explosion of small commercial- and military-grade drones on aerial battlefields. The fight for control of the air will not only include dueling fighter jets, but the hunt for these small, low-cost, and expendable systems. Additionally, these systems can, and will, likely be armed to provide a relatively low-cost precision-strike capability, previously only available to the world’s largest and most advanced air forces. A resource-constrained air force can contest air superiority through the procurement and utilization of large fleets of these systems. The United States and its coalition air forces will need to allocate significant resources to find and destroy these systems.

The use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), UASs, and drones is not new; the United States began using UAVs in large numbers as early as Operation Desert Storm in 1991. The MQ-1 Predator and MQ-9 Reaper were symbols of air operations in the post-9/11 air campaigns. Similarly, the Turkish-built TB2 Bayraktar—which, like the MQ-1 and MQ-9, has potent ISR and strike capabilities—has become the most visible symbol of the Ukraine air war. Additionally, Ukraine received and quickly employed so-called “suicide drones,” such as the US-built Switchblade-300 and Phoenix Ghost, which were observed destroying Russian targets with their small onboard payloads. Ukraine’s success, at least initially, with these systems has led to questions about the future use of UASs in conflict. The Ukraine air war may be providing a glimpse into the future of air operations conducted almost exclusively remotely.

Whereas the counterterrorism conflicts of the early twenty-first century showed the efficacy of ISR and strike UAVs, the Ukraine air war has shown the promise of smaller, relatively cheap, abundant, and expendable UASs and drones. Small, expendable systems, deployed en masse, can have a decisive impact on the battlefield—identifying, disrupting, and even destroying large, armored columns; interdicting resupply convoys; and destroying critical or high-value targets. Large formations of UASs and/or drones will be extremely difficult to defend against in the future, requiring the use of sophisticated electronic-warfare tools, the expenditure of large numbers of expensive air-to-air or surface-to-air missiles, the deployment of directed-energy or high-powered microwave weapons, or some combination of all three categories of weapons. Future air-superiority fights may be defined by the more advanced military struggling to effectively and efficiently allocate resources to the counter-UAS mission, even at the expense of traditional air superiority missions of counter-air and SEAD.

The democratization of spacepower

As with the democratization of airpower capabilities, the shift toward more affordable space-based capabilities will expand the number of nations capable of operating in and contesting control of the space domain. The cost to develop a space program and put satellites into orbit used to be cost prohibitive for all but the wealthiest of nations. This is no longer the case, as evidenced by Ukraine’s use of commercial satellite imagery and satellite communications in this conflict. The rapidly declining cost of spacelift will give more nations the ability to build redundant satellite constellations that will enable critical components of warfighting.

The clearest example of the democratization of space capabilities in the Russia-Ukraine war has been Ukraine’s use of SpaceX’s Starlink services for satellite communications. Immediately prior to launching its ground invasion, Russia hacked Viasat, which Ukraine relied upon for its satellite communications. Two days later, Vice Prime Minister and Minister of Digital Transformation of Ukraine Mykhailo Fedorov asked Elon Musk via Twitter to provide Starlink equipment and services to Ukraine. Musk and SpaceX did just that, sending equipment to Ukraine and allowing it access to Starlink’s massive constellation of more than seven thousand satellites. Despite Russian efforts to jam the signal, Starlink provided Ukrainian forces with secure, redundant, and resilient communications that they have used to control UASs, target artillery strikes, and conduct a host of other military functions.

The Starlink example shows the power of industry in providing high-end, space-based capabilities, but also how nations will use relatively low-cost commercial space companies and capabilities to execute space-based warfighting missions. Ukraine was a unique case, and it is unlikely SpaceX would provide these types of services to an adversary of the United States free of charge. Nonetheless, this example gives a glimpse of how nations—potentially US adversaries or competitors—may take advantage of the changing economics of space operations and use commercial capabilities to execute and support wartime missions. In addition to satellite communications, a host of imagery, weather, and other space-based services are commercially available, and may be employed by the United States’ next adversary. Space will be a contested domain in future conflicts, with multiple combatants able to both operate in and counter their adversaries’ space operations. Space superiority is no longer guaranteed to the United States, its allies, and partners.

The democratization of intelligence

Building a potent intelligence apparatus is an extremely costly venture, usually made cost-prohibitive by the reliance on exquisite, yet extremely expensive, intelligence-collection systems and capabilities. The Ukraine air war, however, has shown that timely and accurate intelligence can be gathered through commercial and publicly available information. Both the buildup to Russia’s invasion and the war itself have shown that the “democratization” of intelligence via open-source intelligence (OSINT) and commercial satellite constellations is here. As with inexpensive UASs and drones, an under-resourced nation can develop a comprehensive and accurate picture of the battlespace through the use of OSINT and commercially available sources, at a fraction of the cost the United States and its friends invest for such a capability.

OSINT is not new, but its use in the Russia-Ukraine war easily surpassed what was seen in any previous conflict. As Russia began a massive military buildup along its border with Ukraine, Internet OSINT analysts were able to use commercial imagery and hand-held photographs and videos to show the buildup of forces and accurately predict the coming Russian invasion of Ukraine. On the first night of the conflict, one of the clear indicators of a coming invasion was traffic apps showing heavy traffic moving south from Bolgorod, Russia, into Ukraine in the early morning hours of February 24—clearly the invasion force moving to initiate its offensive. Throughout the conflict, battle-damage assessment, a mission that even the United States has struggled with mightily, was conducted via OSINT. Oryx, an Internet OSINT analyst, used confirmed and geolocated imagery and hand-held media to confirm the losses of Russian and Ukrainian military equipment, and provided a much more accurate picture of the war’s progress than the overinflated numbers being distributed by the Russian and Ukrainian Ministries of Defense, respectively.

The implication of this democratization of intelligence is stark; nearly any military force can develop a fairly comprehensive and accurate picture of the battlespace through the use of OSINT and the relatively low-cost procurement of commercial-satellite intelligence sources. The most pressing question for intelligence analysts is no longer how they will acquire intelligence sources to observe the adversary, but how to accurately correlate, fuse, and analyze that overwhelming amount of data and correctly analyze the actions taken by the adversary. The United States has traditionally relied on exquisite, but high-cost collection means and only used OSINT to augment the high-end capabilities. The United States and its allies and partners should learn from the conflict and shift their mindsets toward relying extensively on OSINT, and using the exquisite but expensive capabilities to augment publicly available information. A corollary to the democratization of intelligence is the increased emphasis on being able to deny the adversary the ability to accurately assess activity. Deception in war, vitally important since the days of Sun Tzu, will be even more important in the future, and should be a major focus for the United States and its allies and partners.

The democratization of air, space, and intelligence capabilities is not only a threat to the air superiority to which the United States and its allies and partners are accustomed, but also presents opportunities. The United States and its friends can, and should, embrace this trend and recapitalize their air and space forces to provide more capacity at less cost. Lower-cost systems such as UASs, drones, and commercial small satellites, should not replace high-end systems and capabilities such as the F-35 and B-21, but can augment those systems in a high/low mix of capabilities that will provide quantitative and qualitative superiority that should maintain the level of air superiority the United States and its allies and partners have come to expect since 1991.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Though the outcome of the war still hangs in the balance, there is already much to be learned by examining the progress of the air war thus far. The United States and its allies and partners need to use lessons from Russia’s botched air campaign, and they must modify their equipment, doctrine, tactics, and training to account for the democratization of air and space power, which may fundamentally change the character of air and space warfare. By more accurately predicting the future course of aerial combat and designing the force and capabilities to dominate the air and space campaigns of the future, the United States and its friends will be better postured than their strategic competitors to prevail in future high-intensity conflict.

***

Lt Col Tyson Wetzel, USAF is a nonresident senior fellow in the Forward Defense practice of the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security. Wetzel is the deputy director for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) for 7th Air Force at Osan Air Base, Republic of Korea.

Read more essays in the series

Forward Defense, housed within the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security, generates ideas and connects stakeholders in the defense ecosystem to promote an enduring military advantage for the United States, its allies, and partners. Our work identifies the defense strategies, capabilities, and resources the United States needs to deter and, if necessary, prevail in future conflict.

Image: A U.S. Air Force MC-130J Commando II prepares for flight June 30, 2022 at Hurlburt Field, Fla. The Commando II flies clandestine, or low visibility, single or multiship, low-level infiltration, exfiltration and resupply of special operations forces, by airdrop or airland and air refueling missions for special operations helicopters and tiltrotor aircraft, intruding politically sensitive or hostile territories. (U.S. Air Force photo by Senior Airman Jonathan Valdes Montijo)