Colombia needs a strong private sector—and renewed government institutions at the helm

Bottom lines up front

- The foundations of Colombia’s 1991 constitution, including an autonomous central bank and fiscal discipline, have maintained macroeconomic stability despite political volatility.

- Corruption and the rise of illicit economies continue to erode governance and public trust, particularly in rural regions.

- Restoring fiscal discipline and consolidating territorial control are essential to transforming economic stability into long-term national security.

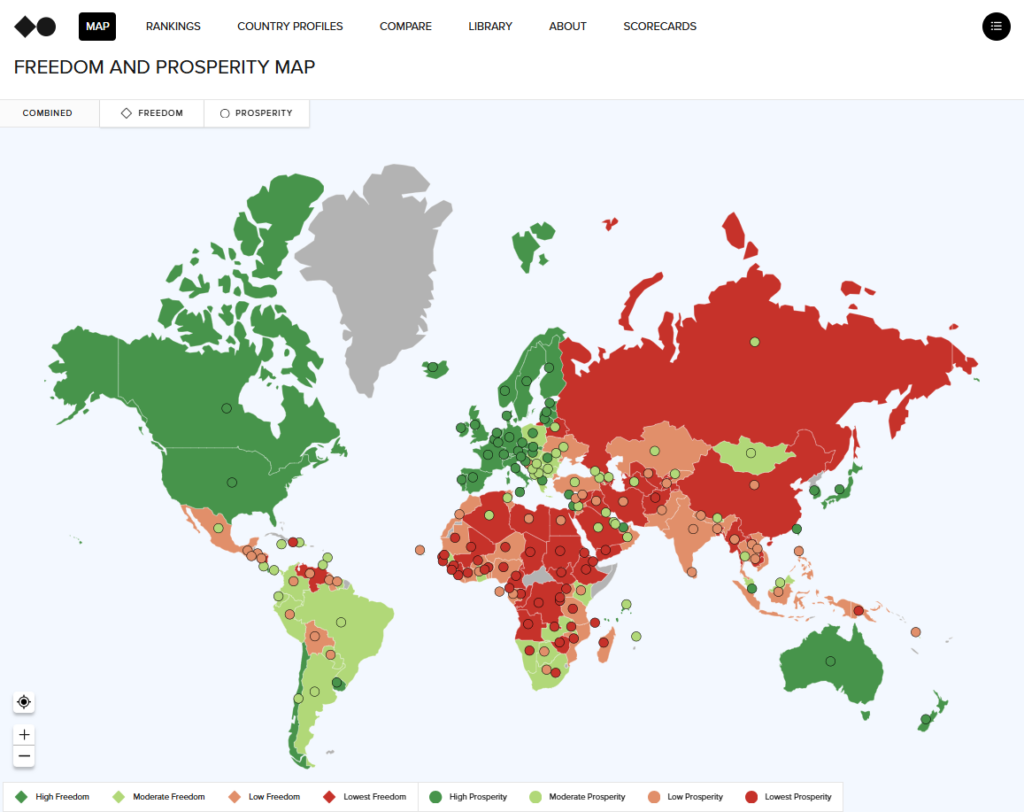

This is the second chapter in the Freedom and Prosperity Center’s 2026 Atlas, which analyzes the state of freedom and prosperity in ten countries. Drawing on our thirty-year dataset covering political, economic, and legal developments, this year’s Atlas is the evidence-based guide to better policy in 2026.

Evolution of freedom

Between 1995 and 2025, Colombia has gone through five institutional phases. Each phase could be characterized by progress and tension, where advances in democracy, improvements in the rule of law, and economic openness were frequently challenged by fiscal limits, political crises, and persistent inequality and informality.

The rooting period (1991–2002)

A fresh chapter of institutional development arrived in Colombia during the early 1990s. The 1991 constitution emerged from a collective determination to eliminate centralism and violence through establishing a participatory and decentralized state which protected rights for all. Social and cultural rights were integrated into the legal framework along with expanded civic freedoms. In addition, the government in the 1990s initiated structural market reforms which included trade liberalization, financial system modernization, and the establishment of an autonomous central bank to manage inflation and create responsible and prudent macroeconomic policies.

Colombia earned economic policy credibility from these reforms which established fiscal and monetary stability for three decades. Nevertheless, these reforms produced a paradox within the country: The economic liberalization process outpaced the transformation of the country’s productive base. As many authors, such as Juan Carlos Echeverry, have noticed, Colombia opened international trade doors without having first constructed its economic base. The nation developed openness, but industries remained defenseless, and infrastructure remained behind. On the other side, the constitution guaranteed a wide range of rights (related to health, education, justice, and more) which had to be funded and created ongoing fiscal burdens exceeding the state’s financial resources. In the 1990s, Colombia emerged as a nation with promising reforms, but its ambitions outpaced its capabilities. This is the tension in which Colombia has operated for many years.

Security and stabilization (2003–2015)

Between 2003 and 2015, Colombia experienced a phase of security along with stabilization. The country managed to regain territorial authority from insurgent forces while attaining public trust in its institutional structures. The government’s “democratic security” strategy was combined with macroeconomic discipline to create a virtuous cycle of investor return, economic growth, and advancement in the rule of law.

During this time, institutional development advanced significantly in response to various policies. A fiscal rule was established while the central bank kept its independence and debt remained controlled. Changes among political ruling parties in Colombia continued without violence while international observers recognized the country’s democratic progress. However, structural problems remained hidden. The security improvements brought undeniable benefits to Colombia, but fighting insurgent forces led to human rights violations that damaged the country’s legitimacy and ability to govern. Colombia made progress on security but failed to improve equality and strengthen its institutions.

Polarization and the post-peace era (2016–2020)

The third stage in modern Colombian history began with the 2016 Peace Agreement, which put an end to fighting with FARC, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, the country’s largest guerrilla force. The peace agreement meant to unite society but instead divided it more deeply. The national plebiscite opposition to the agreement, together with its congressional approval, created an impression that the government had disregarded public opinion.

The government could not maintain the ambitious goals of the peace agreement because it lacked sustainable implementation capacity. The implementation of programs for rural reform and reintegration and financial support for these programs remained insufficient. Progress on truth, justice, and reparation was also uneven. At the same time, non-repetition mechanisms—designed to prevent former combatant or affiliated groups from committing the same crimes and to reduce the likelihood of renewed violence—were only partially carried out. Meanwhile regional territorial conflicts increased as coca production grew (due to the dismantling of aerial coca fumigation), and new criminal organizations appeared. The anticipated “post-conflict” situation was instead a reshuffling of existing threats. By 2020, people in Colombia had grown exhausted and increasingly disappointed that the global celebrations of peace appeared so distant from their actual experiences.

Pandemic and social unrest (2020–2022)

The fourth phase revolves mostly around the COVID-19 pandemic. Although Colombia managed to avoid major economic and social setbacks through its proactive countercyclical economic approach, the pandemic nonetheless revealed structural weaknesses of inequality and informality, which led to multiple indicators falling before they partially recovered in 2021 and 2022. The impact of COVID-19 pushed more people into informal work while increasing poverty and inequality and reducing the number of available jobs. The result was diminished economic freedom. The public protests, in part triggered by illegal support and tax increases announced in the wake of the pandemic, revealed deep societal inequalities and perceptions of corruption and political manipulation. These combined to damage institutional trust, hindering investor confidence and consequently the economy.

Uncertainty and political confrontation (2022–2025)

The fifth phase covers the developments since 2022. The current political environment is marked by a confrontational atmosphere, which disrupted consensus-building efforts and created conditions that decreased investment potential and caused institutional uncertainty that destroyed trust in all government institutions. Since 2022, Colombia has faced fresh difficulties caused by inadequate and debatable policies on energy, public services, education, pensions, health, taxes, and land that drive political polarization and create economic instability. The decline of institutional dialogue has diminished investor trust and created uncertainty about Colombia’s future course while democracy persists. The current state of ideological conflict has displaced the practical economic management approach that used to guide the country’s economic affairs. Colombia now confronts the dual challenge of building trust between government and markets and connecting its citizens with their representative institutions.

The 1991 constitution established institutional structures which form one of Colombia’s most valuable assets. The Acción de Tutela gave citizens legal tools to protect their rights, and decentralization increased local government accountability, capacities, and options. The central bank’s autonomy enabled uninterrupted monetary and exchange rate policy and protected the nation from the populist cycles that ravaged most regions on the continent.

But legal systems cannot ensure freedom by themselves. Governance remains weak due to corruption, excessive regulations, and persistent informalities and social inequalities. Over 55 percent of workers remain outside the formal economy, and millions of firms are microbusinesses with low levels of formality, undermining tax collection and labor protections. Colombia needs to protect its democratic institutions while extending institutional benefits to formalize the excluded population.

Over 55 percent of workers remain outside the formal economy … undermining tax collection and labor protections.

The security situation represents the second vital point in Colombia’s recent timeline. During the 1990s, the Colombian state faced three concurrent threats from drug cartels, guerrilla insurgents, and armed groups that fought for territory; used kidnapping, extortion, and narcotrafficking to fund their operations; and exported large-scale violence to cities. The homicide rate ticked up, and many people were forced to abandon their homes. Business owners lost their local enterprises and had to defend themselves because municipal authority disappeared from vast sections of the country. By 2005, Colombia regained its administrative control and normalized daily activities, which permitted people to travel more freely, reduced transportation expenses, and extended investor horizons. Companies prospered under fiscal discipline and macroeconomic stability, which directed workers toward new regions for economic enterprise.

Over the course of three decades of social and economic development, women gained visibility and access to opportunities in both the public and private sector. Women’s participation in the workforce increased as did leadership diversity and social policies aimed at gender balance. The boost in household earnings together with more stable societies proved that inclusive growth strengthens both economic prosperity and social freedom.

The business environment in Colombia developed according to its political dynamics. Institutional predictability and consistent rules produced the best investment conditions from mid-2010-2020s. The trust in Colombia has been diminished by inconsistent policies and growing polarization since 2022. The business community shows apprehension toward taxation due to its inconsistent design and enforcement.

The country’s most effective reforms happened when governmental authorities joined forces with business leaders and academic experts to craft public policy that integrated regulatory, infrastructure, and labor initiatives to achieve common goals. Economic strategy has lost cohesion because the dialogue that used to inform it has diminished. Because freedom and prosperity depend on a foundation of predictability, the loss of predictability stands as the most critical institutional threat facing Colombia in the short term.

Colombia’s democracy has shown more stability compared to other regional nations, but 2016–18 marked a fundamental change. The nation experienced a rapid deterioration of political rights and a decline in civil liberties during this time frame. The rejection of the peace agreement in the plebiscite triggered political polarization, which worsened after congressional ratification of the plan. This resulted in widespread public concern about the institutional bypassing of political processes. During this period, both cocaine cultivation and illegal mining activities expanded while violence shifted its operational patterns and power dynamics among different actors. The political rights indicator shows further deterioration during the 2020 emergency period, which also witnessed social uprisings, but there was some improvement in 2021–22 once restrictions were lifted.

At present, legal operations are restricted in Colombia because of two fundamental elements. Most labor markets and business activities operate predominantly beyond the formal sector. The rule of law, measured by the legal subindex, experienced a rapid increase in 2014–15, followed by a dramatic decline. Formalization efforts expanded when security conditions improved, and economic activity rose only to retreat once economic performance declined and labor costs increased. Research shows that greater informality reduces enforcement capacity as well as social insurance coverage and tax revenue. Corruption and bureaucratic scandals from 2010 to 2018 reduced judicial public trust, and illegal activities in unregulated territories eroded local government authority.

Inequality, widespread informality, and growing insecurity … had been eroding democratic rights well before the pandemic triggered massive job losses and overwhelmed public services.

Governance quality worsened during these processes even though other sectors showed signs of improvement. While problems existed before the pandemic, COVID-19 made them more apparent. Social unrest spiked sharply in 2019, subsided during COVID-19 lockdowns, and intensified again in 2021. Data reveal that political freedom declined both before and after COVID-19. Yet the underlying causes—rising inequality, widespread informality, and growing insecurity—had been eroding democratic rights well before the pandemic triggered massive job losses and overwhelmed public services. The political situation since 2022 has been more confrontational, hindering consensus-building between government, business, and academic partners and stirring tensions between autonomous institutions and regulatory bodies. The key goal of economic recovery requires the establishment of stable economic directions along with trustworthy dialogue mechanisms that will rebuild private-sector confidence and restore normal market expectations.

Evolution of prosperity

Freedom and prosperity in Colombia have developed concurrently, although their progression has never been perfectly aligned. The 1990s and 2000s market liberalization, alongside expanded rights in the new constitution of 1991 and fiscal and monetary discipline, created the foundation for Colombia’s largest social change in contemporary history. The nation’s average per capita income tripled while poverty dropped by 20 percentage points and life expectancy increased by around ten years. This growth, however, contained a key warning since its uneven distribution meant delayed economic benefits for many Colombians. The clear lesson was that growth without fairness damages society just as severely as economic stagnation.

The inequality trap

Between 2005 and 2016, many observers believed Colombia had entered a positive feedback loop.1Otaviano Canuto and Diana Quintero, “Colombia: Getting Peace, Getting Growth,” Policy Center for the New South, March 23, 2017, https://www.policycenter.ma/blog/colombia-getting-peace-getting-growth; avid Felipe Perez, “After a Decade of Growth and Political Stability, It’s Time to Invest in Colombia’s Future,” World Finance, accessed [insert access date], https://www.worldfinance.com/wealth-management/after-a-decade-of-growth-and-political-stability-its-time-to-invest-in-colombias-future. Economic growth remained healthy while job creation improved, and social programs reduced extreme poverty levels. Market freedom finally found a way to work harmoniously with social policy to benefit society.

People will tolerate slow economic growth, but they will refuse to support a system that fails to reward hard work or equitable treatment.

After 2016, the positive cycle started to break down. Economic growth decreased, and productivity reforms came to a halt while the wealth gap between rural and urban Colombia remained the same. Informal employment increased yet again while people lost hope for their future because inequality returned to its former levels. Then the pandemic struck, revealing structural defects the country had delayed addressing. Education interruptions, female job losses, and strained public finances pushed the country to its limits.

The 2021 protests were triggered by discontent over taxes, but they served to express people’s deeper sense of exclusion. Many Colombians felt that prosperity had become an exclusive privilege rather than a universal promise. The widespread perception damaged people’s trust in democracy and transformed economic inequality into a political moral crisis. People will tolerate slow economic growth, but they will refuse to support a system that fails to reward hard work or equitable treatment.

Colombia achieved indisputable progress through its recognition of Indigenous and Afro-descendant community rights. However, many of these advancements failed to deliver real benefits in practice. From 2010 to 2020, minority inclusion freedom indicators experienced a decline. The absence of governmental security in peripheral regions, combined with ongoing displacement and illegal expansions of mining and drug production, continue to drive social marginalization.

The disconnect between greater formal rights and stagnant living conditions is clearly visible. For many Colombians, equality before the law failed to translate to real equality of opportunities. The main takeaway is that inclusion demands more than official recognition; it requires continuous financing for education, infrastructure, and peacekeeping that creates national investment incentives for all territories.

Since 2018, Colombia has received over two million Venezuelan migrants. Managing this massive influx tested national institutions but also brought new energy, talent, and entrepreneurship to Colombian society. Border communities became overburdened because social services reached their limits. The “Temporary Protection Statute” along with other pragmatic policies transformed what could have been a humanitarian crisis into a demographic boon over time. Formal labor market workers contributed to the economy through tax payments while bringing new and energetic workforce potential. Amid regional tendencies to respond with populist fervor, Colombia demonstrated a distinct approach that blended openness with strategic foresight. Institutional flexibility combined with inclusiveness demonstrated that migration could be a driver of renewal instead of instability.

Colombia has achieved one of its most remarkable successes through environmental policy initiatives. From 2010 through the early 2020s, Colombia transitioned from setting green targets to producing tangible achievements. The economic policy established through CONPES 3934 (2018) and CONPES 4075 (2022) proved that green growth had become an integral economic plan instead of merely aspirational.

The addition of electric vehicle incentives, together with renewable energy auctions in La Guajira and enhanced prosecution of illegal mining, transformed environmental defense into a core competitiveness element. Mercury emissions decreased while wind and solar power capacity expanded, and the nation began perceiving sustainability as an advantage rather than a limitation. Although environmental issues such as deforestation remain, Colombia has advanced to where economic and environmental goals are more in sync.

Human development presents the clearest demonstration of how freedom relates to prosperity. People in Colombia have experienced longer lifespans and enhanced health outcomes over the past three decades. Infant mortality rates dropped dramatically while literacy rates increased, and healthcare access became almost universal. As a result of the 1993 and 2011 reforms, Colombia’s health care systems transformed to become one of Latin America’s most comprehensive.

Education in Colombia remains divided: Urban schools have developed quickly but rural areas continue to lag behind. Digital access and trained teachers remain scarce in many classrooms while educational results show significant differences across regions. The pandemic intensified educational inequalities, emphasizing to policymakers that offering coverage without proper quality or relevance is insufficient. Future development requires better integration between educational systems and productive sectors to create job opportunities which could also lead to social stability.

The path forward

Colombia is approaching a critical point which will define its future direction. Thirty years of institutional advancement delivered stability alongside credibility, yet the country continues to struggle with social inequality, economic informality, and declining public trust. Challenges arose after 2016, when investment diminished, economic growth declined, and political polarization intensified. But the real issue is greater than Colombia’s ability to grow: The crucial challenge is to achieve inclusive growth that transforms freedom into equal prosperity.

The foundation of prosperity rests on establishing stable public finances. After the necessary spending during the pandemic period and the increase in public debt, Colombia started to make a fiscal adjustment which was successfully implemented between 2020 and 2023. However, since then, public debt and the fiscal deficit have risen high enough to make investors nervous. As a result, Colombia needs an effective reform that expands the taxpayer base while making compliance easier; it should also eliminate tax benefits that favor a select few while preserving support for small regional businesses.

The restoration of fiscal rules (which were suspended in 2025) would demonstrate Colombia’s commitment to disciplined governance while enhancing market and public confidence in the country’s fiscal management. Decentralized fiscal authority with proper accountability mechanisms would enable state institutions to connect with citizens more effectively while distributing growth benefits more fairly.

Peacebuilding requires more than negotiation-based approaches while demanding consistent territorial governance. Large rural areas of Colombia still live under alternative and illegal power systems that impose fear instead of upholding legal authority. Road construction alongside internet connectivity and new schools serve as development tools which could also be useful in strengthening citizenship.

Government investments in infrastructure yielded clear advancements across Antioquia, the coffee region, and parts of the Caribbean region in the form of decreased violence, increased job opportunities, and population retention. Security improves only when people have access to opportunities to replace coercive systems. The practical and moral lesson that emerges is that prosperity requires peace, and peace demands governance from a state whose presence is felt where people reside.

Informality blocks the path that unites freedom with a prosperous future. More than 50 percent of Colombian workers lack contracts and protections since they work outside the formal system. The workplace formalization process would be achievable by easing procedures and reducing labor expenses and modernizing ways to connect workers with employers.

Simultaneously, Colombia needs to transition from an extraction-based economy to an innovation-driven economic model. Productivity functions as the link between immediate economic recovery efforts and enduring prosperity. This requires industry-university coordination along with technological implementation support and local business development investment. Subsidies will not reduce inequality nor sustain freedom because productivity growth serves as the fundamental solution.

Colombia’s greatest challenge, however, springs not from fiscal concerns but from the political domain. The current political division has turned policy discussions into entrenched conflicts, making compromise look like weakness. Future development in Colombia depends on institutional pragmatism, which requires leaders to prioritize results over political statements.

Non-negotiables must be to protect the independence of the central bank and to maintain the autonomy of courts and oversight agencies. Dialogue between government, business, and civil society needs to be reestablished through structured channels. Economic freedom depends not only on predictable rules for investors but also on the social contract that allows it to endure. Transparent institutional operations promote both economic and public trust.

Non-negotiables must be to protect the independence of the central bank and to maintain the autonomy of courts and oversight agencies.

The transition toward clean energy creates difficulties while promising new possibilities. Even though oil and gas continue to generate substantial government revenue, Colombia possesses vast renewable energy potential. The appropriate approach involves slow and responsible market transition combined with building new industries based on sustainable agriculture, clean energy, and ecotourism while preserving fiscal stability.

Environmental stewardship could become a competitive advantage when established through consistent regulations and patient investment. Colombia is endowed with geographical diversity, biodiversity, and abundant water resources that would enable green industries to thrive—as long as institutions remain constant, regulations are simplified, and public-private partnerships are strengthened.

Throughout the thirty-year period from 1995 to 2025, Colombia has been trying to balance its aspirations against its limitations. It strengthened its democracy and opened the economy, but it continues to battle persistent problems of inequality, informality, and insecurity. Freedom in the country has never been fixed since each generation must labor to preserve and renew it.

The next chapter depends on Colombia’s ability to tether freedom to present-day opportunities. Achieving fiscal stability together with security systems, educational advancement, and institutional trust is a moral obligation essential for democratic success. Once trust returns to citizens and government bodies, between investors and institutions, and among regions with their central authorities, Colombia will convert its practical liberty to enduring economic prosperity.

The future direction of the nation depends on making decisions between opposing forces, including confrontation versus consensus, populism versus pragmatism, and empty rhetoric versus courageous social and economic reforms. With the right decisions, Colombia can become an example of democratic stability and inclusive development throughout the Americas.

about the author

José Manuel Restrepo is an economist, academic leader, and former public servant with experience in education management and economic policy. He has served as president (rector) in Universidad EIA, Universidad del Rosario, and CESA Business School in Bogotá. He held cabinet roles as Colombia’s minister of commerce, industry and tourism and later as minister of finance and public credit. He holds a master’s degree in economics from the London School of Economics and a Ph.D. in management from the University of Bath.

A strong advocate for innovation, sustainability, and institutional ethics, Restrepo has championed policies such as the Entrepreneurship Law, Green Sovereign Bonds, and the modernization of Free Trade Zones 4.0. His leadership experience extends to academia, government, and business, where he seeks to foster collaboration as a means to turn policy into progress. As a frequent speaker and columnist, he reflects on productivity, education, and governance, emphasizing that economic progress must always serve people.

Explore the data

The Indexes rank 164 countries around the world. Use our site to explore thirty years of data, compare countries and regions, and examine the subindexes and indicators that comprise our Indexes.

Stay Updated

Get the Freedom and Prosperity Center’s latest reports, research, and events.

Stay connected

Read all editions

2026 Atlas: Freedom and Prosperity Around the World

Against a global backdrop of uncertainty, fragmentation, and shifting priorities, we invited leading economists and scholars to dive deep into the state of freedom and prosperity in ten countries around the world. Drawing on our thirty-year dataset covering political, economic, and legal developments, this year’s Atlas is the evidence-based guide to better policy in 2026.

2025 Atlas: Freedom and Prosperity Around the World

Twenty leading economists, scholars, and diplomats analyze the state of freedom and prosperity in eighteen countries around the world, looking back not only on a consequential year but across twenty-nine years of data on markets, rights, and the rule of law.

2024 Atlas: Freedom and Prosperity Around the World

Twenty leading economists and government officials from eighteen countries contributed to this comprehensive volume, which serves as a roadmap for navigating the complexities of contemporary governance.

Explore the program

The Freedom and Prosperity Center aims to increase the prosperity of the poor and marginalized in developing countries and to explore the nature of the relationship between freedom and prosperity in both developing and developed nations.

Image: Bogotà, Colombia, 08.12.2025: colorful building with the colombian flag in the historic center.

Keep up with the Freedom and Prosperity Center’s work on social media