Biden should course-correct to embrace global economic, trade deals

The Biden administration should act to correct its post-Afghanistan foreign-policy malaise by embracing economic agreements that rally its global partners and restore confidence in US leadership.

That effort should begin, but not end, with an embrace and expansion of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) to include the United Kingdom, which has applied to join, and other European partners that have not.

That mouthful of a trade agreement title—not helped by an acronym that is more stutter than vision—has come to symbolize all that is wrong about the American retreat from the brand of international leadership that defined the decades after World War II. That period brought with it a historic expansion of prosperity and democracy, which is now endangered.

Though negotiated by the Obama administration as the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and signed in February 2016, the agreement never entered into force after President Donald Trump withdrew from it upon entering office in 2017. Led by the Japanese, the other eleven signatories moved forward anyway a year later with an agreement that represents more than 13 percent of global GDP, or $13.5 trillion.

Nothing should have awakened the Biden administration more to the attractions of the CPTPP—or to the perils of US withdrawal from it—than last month’s application by the Chinese to join the agreement, coinciding with news of the trilateral US-Australian-UK defense deal, known as AUKUS, which among other things would bring nuclear-powered submarines to Australia.

Beijing has argued that while the United States continues to think about global influence in divisive military terms, China sees its greatest global asset as the size and attractiveness of its economy at a time when most leading US allies—including the entirety of the European Union—have Beijing as their leading trade partner.

The best way to counter this economically driven Chinese effort, which operates under the all-inclusive heading of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), is to launch something even more attractive, galvanizing, and inclusive among democracies.

Biden administration officials would argue that they are already doing just that through Build Back Better World (B3W), the G7 response to the BRI designed to counter China’s strategic influence through infrastructure projects. This is a useful contribution.

Combining an expanded CPTPP, B3W, and a host of other measures could result in a “Global Prosperity and Democracy Partnership.” It could include all willing partners, organized in an audacious manner to reverse three dangerous, reinforcing trends: US international disengagement, global democratic decline, and China’s authoritarian rise as the leading international influencer and standard-setter for the era ahead.

By embracing its global partners economically, the Biden administration would be acting in a manner far more consistent with its own “America is back” narrative than has been its trajectory during an Afghan withdrawal that did little to embrace allies (and effectively returned the Taliban to power). At the same time, it would reflect President Joe Biden’s accurate diagnosis of our current “inflection point” as being a systemic competition between democracy and autocracy.

The AUKUS defense deal may be a welcome regional security arrangement, but it has also strained the alliance with France by undermining Paris’s own $66 billion agreement with the Australians through what one French official called “a stab in the back.”

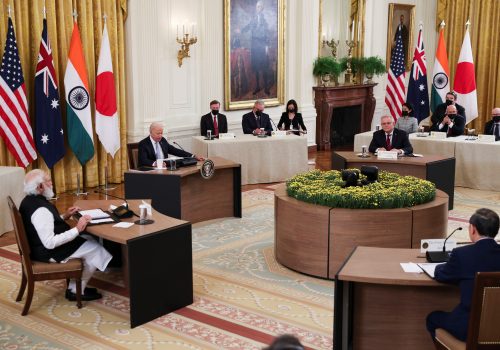

Last week’s Quad summit in Washington, which brought together the leaders of India, Japan, Australia, and the United States, is a significant regional accomplishment. Yet it still fails to address the generational Chinese challenge that is global, economic, and ideological.

Biden administration allies have thus far argued that before one can even consider international economic and trade deals, the president must first focus on domestic affairs: quelling COVID-19 and passing a $1 trillion infrastructure bill alongside a separate social-policy and climate measure, which remain stalled in Congress.

However, it is the international and historic context that gives his domestic plans, under the so-called Build Back Better Agenda, their greatest urgency.

Writing this week in Foreign Affairs, Richard Haass, president of the Council on Foreign Relations, calls for “a new internationalism” that must combine both domestic and global features to succeed.

“The starting point for a new internationalism should be a clear recognition that although foreign policy begins at home, it cannot end there,” writes Haass. “Biden has acknowledged the ‘fundamental truth of the century…that our own success is bound up with others succeeding as well’; the question is whether he can craft and carry out a foreign policy that reflects it.”

Haass’s essay provides a useful and compelling way of understanding the US global leadership role after World War II, as well as the significance of our historic moment.

He begins by provocatively arguing that “there is far more continuity between the foreign policy of the current president (Biden) and that of the former president (Trump) than is commonly recognized” in their rejection of the brand of US internationalism that drove our actions after World War II.

He also separates US global leadership after 1945 into two “paradigms.”

The first, which grew out of World War II and the Cold War, was “founded on the recognition that U.S. national security depended on more than just looking out for the country’s own narrowly defined concerns.” That, in turn, “required helping shepherd into existence and then sustaining an international system that, however imperfect, would buttress U.S. security and prosperity over the long term.”

He sees the new paradigm, which emerged at the end of the Cold War some thirty years ago and still exists in the Biden administration, as reflecting a certain reality: “that Americans want the benefits of international order without doing the hard work of building and maintaining it.”

He rightly uses the word “squander” to criticize US foreign policy after the Cold War. “The United States,” he writes, “missed its best chance to update the system that had successfully waged the Cold War for a new era defined by new challenges and new rivalries.”

President Biden came into office sounding like a leader who wanted to invent a new paradigm for a more challenging global era characterized by a generational Chinese and climate challenge. It was to be one of domestic renewal and international engagement.

He can stop the squandering by charting a course of global common cause among democracies. “In the absence of a new American internationalism,” Haass warns, “the likely outcome will be a world that is less free, more violent, and less willing or able to tackle common challenges.”

The Biden administration still has a chance for bold, decisive action. But that window of opportunity will not be open forever.

This article originally appeared on CNBC.com

Frederick Kempe is president and chief executive officer of the Atlantic Council. You can follow him on Twitter @FredKempe.

THE WEEK’S TOP READS

Richard Haass | FOREIGN AFFAIRS

This week’s must-read is Richard Haass’s powerful warning that the United States is continuing its turn away from internationalism in an era when a strong internationalist approach is more urgent than ever.

“The word that comes to mind in assessing U.S. foreign policy after the Cold War is ‘squander,'” Haass writes. “The United States missed its best chance to update the system that had successfully waged the Cold War for a new era defined by new challenges and new rivalries.”

Should the United States fail, Haass warns, “the likely outcome will be a world that is less free, more violent, and less willing or able to tackle common challenges.” Read more →

#2 The west is the author of its own weakness

Philip Stephens | FINANCIAL TIMES

In his final weekly column, Phil Stephens—long one of my favorite commentators on international affairs—offers a gloomy, but important, reflection on the escalating crises of the world.

“There was nothing wrong with the ambition of the post-Cold War optimists,” Stephens writes. “It remains hard to see how the world can work without liberal democracy and a rules-based international system. What the optimists missed then, and the China watchers overlook now, is the hollowing out of trust in democracy at home.”

Cheers, Phil, for a quarter-century of great commentary. Read more →

#3 China Is a Declining Power—and That’s the Problem

Hal Brands and Michael Beckley | FOREIGN POLICY

Hal Brands and Michael Beckley offer a reasoned, provocative warning: Far from being a rising power, China is entering a period of decline, which makes the risks of Chinese belligerence all the more likely.

China “is an already-strong, enormously ambitious, and deeply troubled power whose window of opportunity won’t stay open for long,” they warn.

The authors argue that the United States must prepare for war not because its rival is rising, but rather because of the opposite. Read more →

#4 The U.S. Has a Way Back on Pacific Trade

Tim Groser | THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Tim Groser, New Zealand’s former trade minister, writes a smart column about how the United States must rejoin the CPTPP if it wants to effectively engage in the Pacific.

“We now need to hear American leaders on both sides of the aisle talking about re-engaging in the region,” he writes, “not only on the political and military levels, but on the trade and economic architecture that will shape economic relations over the next decade and beyond.”

He sizes up the difficulties for the United States in making this move—and all the impediments that lie before the Biden administration—then provides a course of action that is both doable and urgent. Read more →

#5 Inside the CIA’s desperate effort to rescue its Afghan allies

David Ignatius | THE WASHINGTON POST

Amid the chaos and tragedy of the American withdrawal from Afghanistan, David Ignatius offers a silver lining with his reporting on the CIA’s effort to rescue its allies and partners.

“Two former officers,” Ignatius writes, “told me the agency had rescued more than 20,000 Afghan partners and their families.”

This sort of quiet heroism is vital to keeping some form of trust in the United States alive. As Ignatius puts it, “[f]or former CIA officers who served in Afghanistan alongside brave partners, though, this is about closing a circle — one that began and ended with trust.” Read more →

Atlantic Council top reads

Image: US President Joe Biden listens to Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi during the Quad summit at the White House on September 24, 2021. Photo by Evelyn Hockstein/Reuters.