In 1998, as part of a research fellowship, the historian Melvin Small prepared a report for NATO on the early years of the Atlantic Council, which was then thirty-seven years old. His investigation, which captures in rich detail the roots from which today’s Atlantic Council has sprung, is below.

On April 8, 1976, the New York Times and the Washington Post reported that James F. Sattler, a part-time consultant at the Atlantic Council, had been exposed as a secret agent of the state security apparatus of the East German government. His espionage work had been so highly regarded that the German communists had made him the youngest full colonel in their intelligence services. Yet the object of his espionage, the Atlantic Council, which since its founding in 1961 had promoted NATO and European- American cooperation through publication of books and pamphlets and the sponsorship of conferences, was a private organization whose activities never involved classified materials. Moreover, although the Washington Post noted that the Atlantic Council’s board “reads like a who’s who of the so-called ‘Eastern foreign policy establishment,'” the Sattler exposé represented the first time the Council had made headlines.

Why would the East Germans send an agent to work at the Atlantic Council? And how could it be that although its directors included—and still include—virtually all former secretaries of state and scores of prominent diplomats and industrial leaders, few Americans have ever heard of the organization?

While scholars, journalists, and pamphleteers have written widely about the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) and the Trilateral Commission and their alleged pernicious influence on American foreign policy, no one has ever studied the Atlantic Council (ACUS), despite the fact that many extremely influential Americans have belonged to all three organizations. In fact, George S. Franklin, Jr., executive director of CFR from 1953 to 1971, served as the first secretary of ACUS and later as secretary of the Trilateral Commission.

This lack of knowledge about and general interest in the work of the Atlantic Council is all the more astounding considering its sponsorship of some thirty books, well over one hundred policy papers, a group of Academic Associates (mostly historians and political scientists) from almost 400 colleges and universities, and especially the availability of 373 boxes of organizational records through 1980, which are open to researchers at the Hoover Institution.

Few people outside the Washington Beltway know about the work of ACUS in part because its directors have been generally satisfied to act behind the scenes, promoting their ideas and not their institution. Indeed, when in 1995 I inquired about the prospects of interviewing ACUS President David C. Acheson, his executive vice president at first considered rejecting my request on the grounds that I might turn things up that would embarrass members of this very discreet organization.

The Atlantic Council has little about which to be embarrassed. It has been an interesting and, in many ways, unique participant in the US foreign-policy process for more than thirty-five years and has played an important role in promoting and sustaining America’s partnership with Western Europe during the Cold War. An examination of its many complicated interactions with the government, foundations, American elites, and the public offers a revealing look at the way such non-governmental organizations contribute to the foreign-policy debate in the United States. Here I will concentrate on the important formative years of the Council—1961-1975—as it struggled to find a place for itself among the welter of foreign-policy think tanks and Atlantic Community organizations.

Organizational background

ACUS was formed in the fall of 1961 as a response to fears that the Western alliance was fragmenting. The initial series of crises that brought the weak Western European states into alliance with the United States in 1949 had been resolved. A prospering Europe had regained its confidence, the danger of an imminent invasion from the East had receded, and Americans wondered about the need to maintain their costly defense commitments. More particularly, problems had developed within the alliance during the late fifties involving the return to power of Charles de Gaulle in France, the possible participation of Great Britain in the Common Market, the balance of payments, the command and control of nuclear weapons within NATO, and a general feeling of malaise revolving around the feeling that those committed to American-European cooperation who were “present at the creation” of early Cold War institutions like NATO were fast disappearing from the political scene.

Complicating matters was a surprisingly bitter conflict within President John F. Kennedy’s administration among Atlanticists who wanted to move ahead swiftly to establish closer US ties to the continent, Europeanists who contended that Washington’s highest priority should be the promotion of European integration, and those committed primarily to the maintenance of a “special relationship” with Great Britain.

The official debate was mirrored among private citizens concerned about US-European relations. Since Clarence Streit established his Federal Union in 1939, scores of other volunteer groups devoted to Atlantic unity had developed in the United States, often working at cross-purposes with one another, and certainly dissipating energies and resources considered necessary to keep citizens interested in the Atlantic connection.

During the first part of 1961, former Secretary of State Dean Acheson, who at the time was heading up Kennedy’s NATO task force, William C. Foster, the head of the American Committee for an Atlantic Institute and the treasurer of that organization, Adolph Schmidt, an officer of T. Mellon and Sons, and former Secretary of State Christian A. Herter, the head of the newly formed Atlantic Council, Inc., began talking among themselves about bringing together those working for Atlantic unity into one organization.

Foster and Schmidt’s American Committee for an Atlantic Institute grew out of a 1953 initiative of the Second International Study Conference on the Atlantic Community that recommended the establishment of an Atlantic Community Cultural Center. A variety of groups and conferences of citizens and officials of governments and foundations through the fifties followed up that initiative until the NATO Parliamentarians Conference in June 1959 formally approved the establishment of the independent non-governmental Atlantic Institute that would sponsor policy-relevant studies on economic, political, and cultural relations among alliance members and in the international system in general. The Atlantic Institute opened for business on January 1, 1961 with Paul van Zeeland of Belgium as chairman of its board. Several months later, former UN Ambassador and Richard Nixon’s 1960 running mate Henry Cabot Lodge assumed the director-generalship of the Institute, which saw itself as a CFR for the Atlantic community. In a dramatic symbolic gesture, Lodge established temporary headquarters in the Hotel Crillon in Paris. That hotel had been the headquarters of the American delegation to the 1919 Peace Conference, the same delegation that produced a peace treaty scuttled by the United States Senate, in part because of the actions of Lodge’s powerful father. That summer, the Ford Foundation helped launch the Institute with a five-year grant of $250,000. Over the years, the Foundation continued to be the Institute’s chief American supporter, contributing, for example, over $800,000 from 1969 through 1973. Long interested in Atlantic community cooperation, the Foundation had previously helped support the American Council on NATO, the Atlantic Treaty Association (ATA), and the US Committee for the Atlantic Congress.

The other major Atlantic organization in the United States, the Atlantic Council, was the successor group to the Atlantic Union Committee, which had been established to call for an Atlantic Citizens’ Convention. Will Clayton, one of the chief architects of America’s postwar economic policies, had been with Herter co-chair of the official, bipartisan, twenty-person US Citizens Commission on NATO. That commission met with other national commissions in Paris in January 1962 as the Atlantic Convention of NATO nations. The ninety-two delegates, who selected Herter as chair, called on their governments to create a new Atlantic Community beginning with the appointment of a Special Governmental Commission on Atlantic Unity.

From 1962 through 1964, the appointment of that commission was the Council’s most important priority. The connections between the original US Citizens Commission and ACUS were intimate to say the least. Richard Wallace, the executive director of the Commission, a journalist and former aide to Senator Estes Kefauver (D-TN), served ACUS as director general from its inception through 1974. Martha Finley, the Commission’s secretary, served ACUS in a similar capacity through the 1980s. In fact, the State Department agreed that the Council could “borrow” the furniture from the Commission for its first suite of offices in Washington.

Secretary of State Dean Rusk called a meeting to be held in his office on July 24, 1961 to unify the three major Atlantic organizations: the Atlantic Council, the American Committee for an Atlantic Institute, and the less important American Council on NATO, which had been primarily concerned with supporting American participation in the ATA. Although one of the organizers of the meeting, J. Allen Hovey, Jr, the secretary of the American Committee for an Atlantic Institute, had explained to his chief, William Foster, that “confusion and concern that has been expressed by the State Department and the Ford Foundation make it clear that some measure of real consolidation has become indispensable,” the idea for the meeting came from the leaders of the movement; Rusk merely placed an official imprimatur on it. Hovey’s reference to the Ford Foundation cannot be ignored, however.

The Foundation was the largest and most influential donor of grants in the field. Its officers were concerned about the disarray in the Atlantic movement in the United States, initially rejecting, for example, a funding request from the Atlantic Institute because “no member of its Executive Committee was able to say precisely what the Institute was supposed to do.” It was so important as a prime source for funds for internationalist organizations that its officers could easily influence major decisions on institutional and leadership policies.

In April 1960, the foundation considered establishing its own “Atlantic Foundation,” which would develop “new approaches and tools … during the 1960s to meet the problems of an increasingly interdependent and shrinking world.” In a fifteen-page memo, a staffer outlined in detail how this foundation would fund programs to enhance the economic strength of the Atlantic Community, aid less-developed countries, improve economic relations between the East and West, contribute to new educational and cultural opportunities in the Atlantic region, and, in general, assume as its tasks most of those already assumed by existing Atlantic organizations. It was not surprising then that a representative from the Ford Foundation was invited to attend Rusk’s meeting.

Conspicuous by his absence at the meeting was the most famous of all Atlanticists, Clarence Streit, who had agitated noisily over two decades for the immediate establishment of an Atlantic federal union. The organizers worried that the State Department would be upset if Streit was on board because he was “so intense he upset a lot of people.” Although some of those who founded ACUS believed “that Streit is right as to the ultimate answer … a lot of long hard work will be necessary before it comes over the horizon of practicability.”

Attending the Rusk meeting were Herter, Foster, Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., W. Randolph Burgess, chair of the ATA and a former US ambassador to NATO, the diplomat Robert D. Murphy of the American Committee on NATO, Stanley T. Gordon of the Ford Foundation, Michael Ross of the AFL/CIO and board member of the American Committee for the Atlantic Institute, and Ed Cooper of the Motion Picture Association. Rusk “raised the question of whether there is not unnecessary dissipation of effort in non-governmental activities in support of the Atlantic Community.” Herter volunteered on cue that the merger of the American Council on NATO, the American Committee for the Atlantic Institute, and the Atlantic Council would go a long way toward resolving the problem. Considering overlapping memberships in the three groups, there were only thirty-four different people on the combined boards. Clayton, Herter, Mary (Mrs. Oswald Lord), former US delegate to the United Nations, and Lewis Douglas, former US ambassador to Great Britain, for example, mainstays of the Atlantic Council, were also members of the Institute board.

Robert Murphy expressed doubts about the wisdom of the merger and the creation of the new Atlantic Council. Herter told him that the ACUS was formed because Murphy’s group “apparently was not ready to do anything without approval from the State Department.” Herter had earlier written to Burgess about his hopes of creating a vigorous new organization that would be a “pathfinder or leader,” not merely an endorser of the status quo preferred by the State Department.

Rusk made it clear that the “Department was hoping for initiative, research, and, if necessary, the boxing of State Department ears.” He suggested that Adolph Schmidt would be a good choice to work on consolidation with one other person. After Foster suggested Burgess, the assembled group approved the formation of a two-person organizing committee.

On November 11, 1961, the heads of the three committees met formally with their boards to combine their operations. Foster, who presided over the meeting, announced that he was dropping out of non-governmental activities to become the first chief of the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency. The Atlantic Council incorporated seven days later, with the old Council and the American Committee for NATO formally joining the American Committee for the Atlantic Institute since that committee had earned a tax exemption. The certificate of incorporation noted that the organization “shall not in any way, directly or indirectly, engage in the carrying on of propaganda or otherwise attempt to influence legislation.” The highly valued tax exemption would make it difficult if not impossible for ACUS to engage in public lobbying, an issue that led several of its officers in 1976 to take the lead in forming the anti-détente Committee on the Present Danger, an organization that could engage in such activities.

The executive committee of the new organization, renamed the Atlantic Council of the United States, met on December 8, 1961 with Clayton in the chair and Schmidt the chair of the finance committee. The executive committee approved a provisional budget of $250,000, $170,000 of which represented the US contribution to support the Atlantic Institute and $15,000 of which went to the ATA. James Barco took a leave from Time magazine to help manage Council affairs as executive vice chairman. Despite this flurry of activity, Barco worried that “we are making a rather slow start.” Monitoring that activity from the State Department, J. Robert Schaetzel, George Ball’s assistant at Foreign Economic Affairs, wrote in the margin of a December 1961 memo discussing the Council’s program, “What program?”

Barco’s concern and Schaetzel’s cynical comment were warranted. Officers of the new organization met on February 2, 1962 to plan for the first formal board meeting in March. It was clear from the discussion that the participants had expended most of their energies forming the organization—they did not know exactly how to proceed and wondered openly what they would say and do the following month. Herter, fearing that the Ford Foundation might still set up its own organization, advised that if that happened, “we should bow out and bow out gracefully.” Several days later, he spoke to John J. McCloy, the chairman of the board of trustees of the Foundation, about that prospect. McCloy told Herter to go ahead—the Foundation’s plans were “far from settled.”

Recruiting members/raising funds

In preparation for the first full board meeting, Herter and the others had put together an impressive list of chairs and directors, led by the three honorary chairs: former Presidents Hoover, Truman, and Eisenhower. Herter’s vice chair was Dean Acheson, while Clayton chaired the executive committee and Douglas served as his vice chair. Among others on the executive committee were W. Randolph Burgess, General Alfred M. Gruenther, George Meany, and pollster Elmo Roper, while among the first directors were Harvard President James B. Conant, Henry J. Heinz, Time magazine’s board chairman, Andrew Heiskell, Corning Glass Company’s Amory Houghton, Ogden Reid of the Herald Tribune, Dixie Cup’s Hugh Moore, General Matthew Ridgway, Adlai Stevenson, and IBM’s Thomas Watson, Jr.

The Atlantic Council has never had difficulty attracting impressive national political and corporate leaders to its key positions and board of directors. After Herter left the chair to serve as Kennedy’s special trade representative, General Lauris Norstad succeeded him. The highly respected diplomat Livingston Merchant took over in 1967, followed by Randolph Burgess in 1971, former Treasury Secretary Henry Fowler in 1973, former Ambassador to Germany and councilor to President Richard Nixon Kenneth Rush in 1978, and General Andrew Goodpaster in 1985.

The recruitment of preeminent national figures was—and still is—an important matter for ACUS, and not just for prestige purposes. A significant percentage of the Council’s operating budget came from contributions from board members, with officers suggesting politely in 1962 that an initial contribution of at least $100 would be helpful. This need to raise money from board members helps to explain why ACUS recruited over eighty board members by 1964, while the much better endowed CFR had fewer than twenty board members.

This policy of relying on board members directly—and their corporations indirectly—for financial support paid off. During its first year, the Council received contributions of $6,000 from Clayton, $5,000 from IBM, $2,500 from Heinz, and $2,500 from Corning. The first forty-nine directors contributed $50,000 to help ACUS get started.

At this point the Council’s needs were modest. During the 1961-62 fiscal year its direct expenses of $74,269 included $34,418 for salaries, $5,000 for rent, and $5,262 for literature. As with most successful organizations, the Council’s budget soon began to grow—reaching $500,000 by the late seventies, $750,000 in the early eighties, $1 million by the end of that decade, and $2.5 million in 1993.

Time and again since 1962, ACUS officers had to go hat in hand to board members to ask for help with nagging periodic budgetary shortfalls. The Council, according to Joseph Harned, who held positions of great responsibility in the organization from the late sixties to the nineties, was “always a shoestring operation.” The Council had to “squeak by,” contended John Grey, the longtime head of its energy studies, because it was “never sophisticated about raising money,” even though many board members were “multimillionaires.”

Fiscal crises were exacerbated by the Council’s practice of beginning projects before it had raised money for them. It was not until 1983 that board chair Kenneth Rush urged the adoption of “a stricter rule” about not starting projects until funding had been obtained.

To help make ends meet, the organization invented a variety of new membership categories over the years, including Patron, Senior Councillors, Councillors, and Honorary Councillors. The “Patron” category, for example, introduced in the seventies, went to people who were willing to contribute $5,000 a year. From a board of fewer than forty members in 1962, ACUS now boasts roughly over one hundred directors, more than fifty senior councillors, and close to two hundred councillors, among other titles. One corollary of this approach of expecting board members to make hefty contributions annually was that ACUS could not recruit too many members of modest means, such as college professors, especially if they did not come from the Eastern seaboard. For one thing they could not afford the expected “dues,” but more important, in most cases they could not afford the travel costs for meetings.

The fact that the organization struggled with finances through most of its history to the point where it had to recruit more and more dues-paying members belies the notion that it was intimately tied to the government, especially considering that other volunteer organizations were receiving under-the-table subsidies from the Central Intelligence Agency at the time. One would have expected such an elite club, full of well-connected and wealthy diplomats and executives, never to have much of a problem making ends meet. Yet in the fall of 1973, it characteristically found itself “in perilous shape” and “scraping the bottom of the barrel.” Two years later, Achilles complained to Schmidt, “We continue to live from hand to mouth financially.”

Quite reluctantly, in the fall of 1974, ACUS finally decided to accept government contracts. Even then, the Council adopted guidelines prohibiting the acceptance of funds for government projects in excess of 35 percent of its total budget. Further, government projects could not involve classified documents and had to be made public.

ACUS prided itself on its relatively independent stature. Early in 1974, for example, despite serious financial difficulties, Theodore Achilles warned his colleagues about accepting too much support from oil companies. He worried about whether taking such largesse would compromise the Council’s ongoing energy studies.

Establishing a program

At the first ACUS board meeting in March 1962, Herter perpetuated the myth that the three organizations had joined together at the prodding of Secretary Rusk. He explained that the main purposes of the new group were to support the Atlantic Institute and the Atlantic Treaty Association and to build programs for Atlantic cooperation in the United States. On the latter, these programs could include issues relating to the development of a statement on the free nations of the world, the Common Market, currency problems, educational activities in the developing world, educational and cultural exchanges with Europe, and analyses of Sino-Soviet issues. As Ernest Barco elaborated several weeks later, the subjects might be explored by the Council’s sponsorship of original publications, reprinting materials, and establishing a speakers program. The three main targets for its activities would be opinion leaders, potential contributors, and the general public. In that regard, executive board member Elmo Roper suggested an opinion survey that might cost from $25,000 to $30,000 to see where the nation stood on the Atlantic idea. The Council had already received more than $100,000 from corporations, a figure that included $50,000 from the Ford Foundation for part of the US payment to the Atlantic Institute. Despite the appearance of activity, very little happened over the next few months. George Franklin worried in May that some of the new directors “were a little impatient our program hadn’t yet got off the ground.”

The fact that the program was slow in developing should not have been surprising. When the three original organizations merged, “grandfathering” in all board members, they brought together a core group of strong personalities like Theodore Achilles, a former State Department counselor, Will Clayton, who chaired the executive committee, and finance chair Adolph Schmidt, all of whom believed in Clarence Streit’s program. Many of their colleagues, however, were unwilling to consider pushing for a union in the near future. Further, the bipartisan board included liberals and conservatives and Republicans and Democrats who did not always see eye to eye. One member expected that the “liberal” Herter would dominate the board on which liberals allegedly outnumbered conservatives by almost six to one.

In truth, throughout its existence, almost all board members and directors generally came from the moderate internationalist wings of both parties. Because the leadership came from both parties, ACUS was able to maintain close relationships with Democratic and Republican administrations, generally sending the same messages with one of its Democrat officers and one of its Republican officers to their respective party’s platform committee hearings every four years to make the case for the Atlantic Community. This calculated bipartisanship also meant that as administrations changed from party to party, ACUS would always have some of its former board members in place in positions of influence. For example, in 1981, former board members Vice President George Bush, Secretary of State Al Haig, CIA Director William Casey, and ACDA director Eugene Rostow, among many others, assumed key positions in the Reagan administration, while members of the outgoing Jimmy Carter administration soon joined the board.

The party differences caused few problems. But the different theoretical approaches to the Atlantic Community did. J. Allen Hovey thought that the passionate differences between the “Federalists,” who were interested mostly in “exhortation,” and the more realistic “Gradualists” led the Council to spend much of its first five years trying “to find itself.” Some Federalists, like Achilles, also clashed with internationalist colleagues who were supportive of the United Nations and other more universal international institutions.

Clayton, who in 1966 resigned from the boards of the Atlantic Institute and ACUS several months before he died because he felt they were not doing the job he expected, claimed the Council was “organized to promote the integration of the free world.” While he was convinced that ACUS was “well organized and well run,” he was upset that the Atlantic Institute had been diverted to undertake Latin American studies.

Looking back at the early years, Schmidt, one of the most prominent Federalists, felt that the merging of the three groups was “a basic error,” considering the different purposes of the organizations. He thought that the Atlantic Council had been formed “for the purpose of obtaining the appointment of the Special Government Commission,” recommended at the 1962 Paris Conference. He assumed ACUS would be “an action organization,” which should have left research work to the Atlantic Institute, and saw Dean Acheson behind the successful attempt to shelve the commission idea and to slow the Atlantic federation movement.

ACUS and the Kennedy administration

The Kennedy administration was interested in the private volunteer organizations devoted to the Atlantic cause, if only because so many influential leaders were involved in their activities. Former diplomats in the leadership of the movement maintained close contact with their old colleagues at Foggy Bottom. Even though the European desk people did not always appreciate “advice” from ACUS officials, they invariably listened patiently to them, although the exceedingly skimpy paper trail in the departmental and presidential archives suggests that ACUS activities rarely were a major matter of concern.

For some ACUS officials, the cozy relationship with friends at the State Department was not necessarily a productive situation. For example, John McCloy was nervous about selecting an American diplomat to replace Lodge at the Atlantic Institute in 1963 because they “pay too much attention to what the State Department thinks.” Exceptions to the rule were McCloy himself and Achilles, “who love to say the State Department is wrong.”

While the Department was pleased with the organization of ACUS, which it saw primarily as a NATO support group, it expressed concern from time to time about its overly enthusiastic and unrealistic interest in “federation now,” symbolized by the Council’s advocacy of the Declaration of Paris principles. The department also worried about ACUS members committing diplomatic gaffes. When a European leader was invited to a small, private Atlantic Council dinner in 1962, J. Robert Schaetzel suggested that the Department send an official escort with him so that it could keep track of what Council members were doing and saying. Schaetzel also expressed concern about the “simple and misleading” term “Atlantic Community” members of ACUS were fond of using; he preferred Jean Monnet’s “European-American Partnership.” (Schaetzel later became head of the Jean Monnet Council.)

On another occasion, a State Department aide worried about “Achilles Latest Opus” about federalism: “It is clear that no one is going to stop the Council’s ‘hawks’ from floating such nonsense.” Achilles, who retired from the Foreign Service in 1961, spent a good portion of the rest of his life as executive vice-chairman in residence (with his own permanent office), directing the activities of the Atlantic Council as a sort of éminence grise. According to Adolph Schmidt, he assumed his position “by osmosis,” in part because while most of the directors had jobs and interests elsewhere, Achilles made the Council his main vocation. Well-off financially, from time to time Achilles made extra contributions to the perpetually financially strapped organization. More important, in February 1965 he helped set up, in effect, his own foundation, the North Atlantic Foundation, which contributed funds to ACUS and other related organizations. Throughout the life of the Foundation, Achilles ran it almost single-handedly, despite the existence of a board of trustees. The Foundation, which for tax purposes came under formal control of ACUS in 1973, contributed as much as $75,000 per year to the Council, with the $45,000 grant in 1984 closer to the norm. By 1992, the foundation had contributed $1.8 million of the Council’s $2 million endowment.

In 1963, General Lauris Norstad assumed the chairmanship of the Council when Herter left to become Kennedy’s special trade representative. It was at this point that Achilles’s role began to grow because Norstad was more of a figurehead than Herter. Schaetzel was fed this information by an “informant” on the board who was concerned about Achilles’s increased influence. For his part, Achilles, who felt that Herter, Clayton, and Norstad enjoyed the respect of Rusk, Kennedy, and Lyndon Johnson, was convinced that Schaetzel “sabotaged” their ideas in the Department.

Achilles was correct. Norstad’s friends in the State Department politely rejected his request that they appoint Achilles to head a special commission to develop the 1962 Paris proposal. If there had to be a commission, Schaetzel’s own choice for chair was former CFR Research Fellow Ben T. Moore. He hoped Moore would first take over the Atlantic Institute to get that institution out of the hands of the Atlantic Council, which “to a man [is] staffed by people hostile to the European Community.” He proposed using Acheson to affect the change and then work through McCloy, the head of the Ford Foundation, to sweeten the Atlantic Institute’s pie with more funding. Of course, Schaetzel’s first choice was delay by having the Council establish a study group on the commission. Stanley Cleveland, director of State’s Office of Atlantic Political-Economic Affairs, considered the US Citizens’ Commission on NATO to be ten years of a “propaganda effort by Streit”—”something of a mouse.”

Schaetzel’s involvement with Ford Foundation funding was not unusual. On one occasion, the Foundation’s Shepard Stone asked him directly for his opinion on how to strengthen the Atlantic Institute, including questions of personnel. In similar fashion, a representative from the Rockefeller Foundation asked Schaetzel for his opinion about the value of a proposed Atlantic Institute study on the Common Market and the United States. Former high government officials John J. McCloy and McGeorge Bundy headed the Ford Foundation during the sixties, while aides like James Huntley moved from the Atlantic Institute’s Washington office to the Ford Foundation to serve as a program officer. Before he joined the foundation in 1965, Huntley urged Assistant Secretary of State William Tyler to tell the foundation’s agents, should they ask him, that the Atlantic Institute was or could be a worthwhile research institution.

The indefatigable Huntley was one of the most important of all the Atlanticists, and not just because he helped create the Atlantic Institute and worked for the Ford Foundation. He played a major role in organizing the Committee on Atlantic Studies and the Atlantic Luncheon Clubs and Mid-Atlantic Clubs, created the Standing Conference of Atlantic Organizations and the Committees of Correspondence, and served briefly as secretary general of the Atlantic College movement and as ACUS president.

Despite administration officials’ distaste for the meddling of Council Federalists in their European policies, they deferred often to them because of old friendships and the prestige of the ACUS board. For example, National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy, on rejecting an offer to become a sponsor of the Council, wrote to Herter that “The Council is a group of distinguished private citizens and is making a major contribution to public understanding of most important issues.” President Kennedy also felt it politic to drop by a dinner for Lauris Norstad at the Mayflower Hotel in Washington in January 1963 and to meet with him in July to discuss how “the valuable talent available in such organizations as the Atlantic Council [could] be put to use in dealing with the problems of the Atlantic Alliance.” Norstad had asked the president at a July 25 meeting to move on accepting the recommendations from the Citizens Commission on NATO. Gently and obliquely rejecting the request, Kennedy told Norstad, “the most effective course at this time would be to have interested private and parliamentary groups examine on their own some of the key substantive issues before the Alliance,” which included the balance of payments, trade, military strategy, developing countries, and Eastern Europe. “Given the prominence and prestige of the Council’s own members, I am sure that an inquiry by the Council into these and other critical questions would attract equally talented Europeans.” In other words, the time was not ripe for any dramatic initiative from the administration in Europe, although Kennedy recommended a follow-up meeting with Rusk and his aides.

Two weeks before Kennedy’s death, Clayton, Herter, and Norstad met with State Department personnel to discuss the Special Government Commission once again, in a “shambles” of a meeting. According to a Department aide, the “more active elements” in the Atlantic Council were upset about the “foot-dragging position” of State. On a positive note, pleased that Walter “Red” Dowling, a former US ambassador to West Germany, was going to replace the ineffective Lodge at the Atlantic Institute, he was willing to help the Institute get more foundation money.

Reflecting State Department views, Acheson advised his colleagues on the ACUS board that “it was not always necessary to support the government but instead to do things that were sensible; don’t let his organization get the reputation of being a crank. Please be realistic and thoroughly sensible.” Atlantic Institute official James Huntley, who also worried about the conflict between members of the Council, led by Achilles and Wallace, and the Department, urged the group to get on with sensible activities such as educational programs.

ASUS develops a program

In its early years, while ACUS was toying with developing a formal research program, it did engage in a variety of “sensible” activities. For one thing, Elmo Roper completed his ACUS-commissioned poll on “American attitudes toward ties with other democratic countries” in November 1963. Among its findings, introduced by Senator Frank Church (D-ID) and published in the Statistical Review (January 4, 1964) and reprinted in the Bulletin of the National Association of Secondary School Principals (May 1964), were that 67 percent of those polled agreed that US survival depended on its allies and 78 percent approved of international organizations. In general, the poll offered the gratifying conclusion that Americans appeared to be more internationalist than they had ten years earlier.

Nonetheless, ACUS saw as one of its prime missions the monitoring of American opinion on the Alliance and making certain that isolationism would never reappear as part of the national political debate. In 1969, it ran a $67,000 advertising campaign to celebrate NATO’s twentieth anniversary. With the J. Walter Thompson agency contributing its expertise and comedian Bob Hope serving as spokesperson, the campaign placed ads in 8,000 newspapers and fifty magazines and on 5,000 radio stations and 710 television stations. It always helped to have friends in high places. When CBS chair William Paley found the advertisements too “controversial” and worried whether he would have to provide equal time for anti-NATO people, John McCloy interceded to convince the station to run the ads. In the end, ACUS claimed it received almost $400,000 of free television time. In addition, it was no coincidence that year that the national high school debate issue related to NATO.

For the twenty-fifth anniversary NATO campaign in 1973, ACUS recruited as spokesperson Dallas Cowboy quarterback Roger Staubach, who, more than Bob Hope, was “one way of reaching youth,” the prime target of the campaign. That year, ACUS claimed that it received one million dollars of free air time from the networks for the campaign.

The organization’s most important early program decision was to publish a journal, the Atlantic Community Quarterly. Edited by Achilles and Wallace, the first issue appeared in March 1963. The editors promised that the quarterly would present no single point of view other than that “The Atlantic Community is a historic inevitability and that somehow, despite temporary setbacks and diversions, a true Atlantic Community will come into being during the lifetime of most of us.” That community would be the next step from the nation-state, “tying together for certain functions—military, economic, political—nations on both sides of the Atlantic.” Ten years later, the editors claimed “we were right 10 years ago… The Atlantic Community was ‘an historic inevitability.'”

Bound in thick paper, roughly the same size and using comparable print face as Foreign Affairs, despite appearances, the quarterly was not in direct competition with that far more prestigious journal. Like its parent organization, the quarterly rarely made headlines. Reprinting articles, speeches, press conferences, and conference reports, it did not commission original articles until its last issues. In fact, its first number included Christian Herter’s January 1963 article from Foreign Affairs. (The Atlantic Institute’s own journal, Atlantic Studies, which began publishing in 1964, did feature original studies.) This is not to say that its compilation of Atlantic-related source material, including bibliographies, was not useful. The quarterly was a publication of record for the Atlantic community.

But it had a small circulation; its press run generally ranged from a low somewhat below 2,000 to a high of over 5,000, although it began with a circulation of 6,537. There was a finite market for such a publication. The publisher received only five new subscriptions after sending out 5,700 advertising leaflets in 1967. Although the circulation was somewhat disappointing, ACUS has always been interested in influencing opinion leaders. As Henry Adams once wrote, “The difference is slight, to the influence of an author, whether he is read by five hundred readers, or by five hundred thousand; if he can select the five hundred, he reaches the five hundred thousand.”

The journal was a financial drain on the Council, which held its price to $1.50 an issue during its first decade. During its first year, it took in $21,000 but cost $40,000 to publish. Most of its sales were through subscriptions, which one could still purchase for $10 in 1976. By the time it ceased publication in 1988, it was distributing fewer than 1,500 copies and had shrunk to less than 100 pages from a high of 150 pages.

Throughout its early history, ACUS also published a free monthly newsletter, which had as many as 6,500 subscribers. The newsletter offered Council and Atlantic Community news, short articles, accounts of conferences, and other material useful to those concerned with European-American relations. In many ways, considering its circulation, it was a more valuable potential molder of opinion than the journal.

ACUS also became a center for informal get-togethers for prominent visiting Europeans. For example, on September 14, 1964, the organization hosted a reception for a delegation from France. Among those Americans who greeted the visitors were Admiral Arleigh Burke, the columnist Marquis Childs, General J. Lawton Collins, Senator J. William Fulbright (D-AR), Secretary of the Treasury Henry Fowler, General Alfred Gruenther, Senator Vance Hartke (D-IN), Senator Jacob Javits (R-NY), Senator Edward M. Kennedy (D-MA), and Senator Clairborne Pell (D-RI).

ACUS provided office space and a mailing address for the American Council of Young Political Leaders (ACYPL), an organization jointly directed by the Young Republicans and Young Democrats, which held conferences and provided briefings, materials for research, and study tours for its constituency. But it had no “legal or actual control” over it. The organization, linked to the Atlantic Association of Young Political Leaders, was open to people under forty.

In the summer of 1964, ACUS established a Committee on Atlantic Studies devoted to establishing Atlantic Studies programs in American colleges. The Atlantic Institute’s James Huntley was one of the driving forces behind the idea. The University of California at Berkeley and Stanford University began pilot seminars on the project. The Atlantic Institute established a parallel European group, the Committee on European and American Studies (CAES) in Europe, in 1966. The two committees merged in September 1967 and held small workshops and conferences on both sides of the Atlantic. This was the first of several ACUS projects to enhance curricular offerings on Atlantic Community subjects at American universities and part of a strong ACUS interest in making certain that the “successor generation” of leaders was as devoted to the idea of the Atlantic Community as its own generation had been. As one board member worried several years later, “how were we going to educate these young people today when there are no sympathetic instructors in the colleges?”

CAES, however, got off to a rather slow and unimpressive start, at least from the perspective of the Ford Foundation. After supporting travel grants and study awards for the July 1969 meeting in Paris, the program officer, who thought the organization “continues to wander about in search of role,” had failed in “stimulating new collaborative research,” and had failed “to involve promising young scholars in its activities,” recommended no further funding until progress could be shown.

On the secondary level, ACUS worked with the Atlantic College movement, a program that offered two years of international education for young people between sixteen and nineteen at the Atlantic College in Wales, which had opened in 1962. For a while, Lord Mountbatten chaired the movement. The Old Dominion Foundation contributed funds to the Council for scholarships for American students.

The economy of the Atlantic community

The Council’s first three monographs dealt with European-American economic and trade issues. Throughout its history, ACUS devoted a good deal of its energies to economic matters. For one thing, conflicts over tariffs, subsidies, the balance of payments, and the free flow of capital dominated much of the political agenda between the Europeans and Americans throughout the Cold War. Like many in Washington, ACUS officials continually expressed concern that some of those conflicts might ultimately weaken the cohesion and strength of the alliance. In addition, the Council received a good deal of its operating funds from corporations and foundations interested in those issues.

ACUS publications continually called for the lowering of tariff barriers and any other barriers to free trade, especially those that the Common Market had erected. In addition, they advocated increased private US investment in European economies, a capital movement that would lead to greater economic integration and thus greater political integration within the Community. These themes appeared in the publication in 1963 of the first monograph sponsored by ACUS, “Conference on the Atlantic Community,” the proceedings of a conference held in March 1963 that had been organized and funded by the University of California Extension and the University of California Business School and printed by the University of California. Concerns about protectionism and especially France’s recent veto of British entry into the Common Market dominated the proceedings. Among those who participated were Randolph Burgess of the Atlantic Treaty Association, Victor Rockhill, president of the Chase International Investment Corporation, who called for more US investment in Europe as a means to better understanding between nations, John Exter, senior vice president of First National City Bank, and the United Auto Workers’ Irving Bluestone, who, not surprisingly, was alone in calling for greater US national planning in the continental mode.

In 1966, the Council published a much more substantial and impressive monograph, “The Atlantic Community and Economic Growth,” the proceedings of a conference of European and American officials and business leaders held at the General Electric Institute in Crotonville, New York in December 1965. The Crotonville conference was the third in a series of conferences that included earlier meetings in Paris and Fontainbleau. The Council began the Forward with a statement of belief “that the basic aim of economic policy is economic growth and that business should be free to develop and to operate within the Atlantic business community with minimum hindrances from national restrictions.” The conference was organized by the chair of the Council’s Committee on Trade, Monetary, and Corporate Policy, Samuel C. Waugh, a former president of the Export-Import Bank. ACUS would always have such a committee. Aside from the Secretary of Commerce John Connor and Secretary of the Treasury Henry Fowler, CEOs and other high officials from most of the major US firms dealing with international trade were in attendance, including General Electric, American Telephone and Telegraph, US Steel, Texaco, Proctor and Gamble, Standard Oil, IBM, and Gillette. They were joined by officials from chambers of commerce from the United States and Europe to listen to speeches by Fowler on “Expansion and Interdependence,” Dowling from the Atlantic Institute on European businesses, and Olivier Giscard d’Estaing, the director general of the European Institute for Business Administration, on multinational corporations.

The themes of the conference were interdependence, the necessity for American investment in Europe, and support for the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (GATT) and any measures that lowered tariffs. In addition, developing a soon-to-be-common ACUS theme, participants urged American investors to show more sensitivity to local cultures and customs. Finally, the report expressed cautious approval of liberalization in East-West trade, something that interested Europeans more than Americans at that point. Although the conference produced little that was new or unusual, it served as an informal setting for the Atlantic Community’s corporate elite and government officials to meet to discuss common problems.

The Council’s first real “book,” Building the American-European Market…Planning for the 1970’s, based on two years of research and survey activities and meetings, appeared in 1967. Among those who introduced reports on investments, technology, management practices, and trade beyond the Atlantic Community were David Rockefeller, Gerard Phillippe, chair of General Electric, Fritz Berg, the president of the Federal Association of German Industries, Eric Wyndam White, the director general of GATT, and former NATO Secretary-General Paul Henri Spaak. The ACUS reports and surveys were based in part on the three previous conferences and the follow up to Crotonville in Geneva in 1966.

Participants contended that many mutual fears and misunderstandings could be overcome through conference activities and publications such as this one. In addition, businesses throughout the Atlantic Community needed to work together more to help governments devise foreign economic policy and the United States needed to assist Europe with technology transfers.

Again the Council called for lowering barriers to trade and investment, a modest opening up of trade with the East (although the Soviet Union had not yet earned the right to long-term credits), and more assistance to the economies of the developing world. Not very astounding recommendations, but as we shall see, few observers ever accused Council publications as representing the “cutting edge.” The absence of truly dramatic or daring proposals was in part a product of the need for Council committees to achieve consensus among conferees from different countries representing business and government and different positions along the political spectrum.

These four meetings produced the Committee for Atlantic Economic Cooperation (CAEC), which was launched primarily under the auspices of the Atlantic Institute in April 1967. This organization devoted itself to working on trade liberalization, investment policies, and investment in the developing world.

During the period 1969-1973, over 160 corporations contributed to the Atlantic Council. Most of the contributions, however, were under $1,000, with for example Newsweek giving $500 per year and Morgan Guaranty as little as $250 for three of those years. In 1973, while ACUS received $114,000 from corporations, directors gave $110,000. Needless to say, board members were concerned about the level of corporate giving. Treasurer Percival F. Brundage complained that “The value of the Council’s work [to American corporations] is worth at least ten times what goes in,” while Burgess thought it was time to “turn the thumb screws” on corporate sponsors. To their concerns, Gene Bradley suggested that ACUS might not have been doing enough to advance US business interests and that the Council might consider working more on projects of interest to the multinationals. As late as 1992, the Council’s Business Advisory Committee was still concerned that US corporations did not have enough influence in directing the Council’s attention to its problems.

ACUS political research programs and policies

Aside from getting its economic studies under way, the Council naturally was interested during its early years in developing political projects and programs. But launching activities started in that more controversial area proved to be difficult.

After years of hectoring the Kennedy and Johnson administrations about the intergovernmental commission, the Council had failed to influence policy, despite Secretary of State Rusk’s earlier comments about welcoming suggestions from ACUS. In 1970, five years after her father, Will Clayton, resigned from the board, Ellen Garwood submitted her resignation, denouncing the “foot draggers” who should have been more vigorous in pushing the Atlantic idea. She suggested drawing a lesson from the communists who have shown that a “few dedicated individuals can do more for a cause than a large number of particularly dedicated adherents.”

ACUS was concerned about such criticism. In the fall of 1966, after five years of operation, the board had not given up on creating new Atlantic institutions such as an Atlantic Assembly called for at the November 1966 NATO Parliamentarians Conference. But it had other pressing interests as well. As it would throughout its existence, ACUS expressed caution about growing European—and American—interest in détente. While the board members “approve exploration of any reasonable possibilities for sound improvement in relations with countries of the Communist bloc, we do not believe there has been any change in these relations which would justify reduction in the military strength of the Alliance or weakening the credibility of its deterrent power.” This determination to keep US powder dry while not shutting the door to improved East-West relation appeared in most ACUS materials throughout the Cold War, but especially from the mid-sixties through the seventies.

During the seventies, ACUS found its stride, particularly in terms of publishing solid, if not spectacular, research monographs, often based on the work of distinguished international study groups dominated by practitioners, not scholars. Most of the books and monographs … dealt with mid-term not immediate policy issues.

As for the rest of the agenda, ACUS called for freer trade, strengthening the Organization of European Community Development (OECD), improving business conditions within the community, burden-sharing within NATO, increased cooperation and exchanges among students and scientists, and especially “Education of all American school children, students, and adults in the fundamental facts about the Atlantic Community.”

Setting the agenda was a lot easier than implementing it. Two years later, Brundage thought that the CFR, the Foreign Policy Association (FPA), and ACUS could show “no demonstrable results on our foreign policy from any of our separate studies.” He recommended that representatives of the three organizations meet together to “get out of our present mess.” Several months later, ACUS leadership recognized that more had to be done to improve the circulation and content of the quarterly, develop more contacts with citizens’ groups in other countries, improve public awareness of ACUS and its activities, especially the ACYPL that had held it first annual conference the previous spring, and develop new research projects.

Part of the problem was the American concentration on the Vietnam War, which deflected administration and public interest from European issues. Through the Johnson administration, ACUS leaders generally supported US policies in Vietnam. When the Johnson support group, The Citizens Committee for Peace and Freedom in Vietnam, chaired by Presidents Truman and Eisenhower, was formed in 1967, four members of the board of directors and twenty-two sponsors of the Council signed up. Interestingly, that bit of partisan news was reported in the newsletter.

The year 1968 was a turning point for the Council and the Atlantic Community in general. First, the French spring “revolution” led to Charles de Gaulle’s resignation in 1969. ACUS was pleased that Georges Pompidou replaced the single greatest European obstacle to the American vision of an Atlantic Community. In addition, the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968 led to an “awakening” of NATO that “had fallen into a turgid rhythm.”

During the seventies, ACUS found its stride, particularly in terms of publishing solid, if not spectacular, research monographs, often based on the work of distinguished international study groups dominated by practitioners, not scholars. Most of the books and monographs, as was the case throughout ACUS’ existence, dealt with mid-term not immediate policy issues.

One exception was an ACUS-commissioned study that resulted in Timothy Stanley’s Detente Diplomacy. Stanley, a defense advisor to NATO and a visiting professor at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS), with which ACUS enjoyed close relations, consulted with a team of twenty experts brought together by ACUS to deal with the Soviet invitation for a Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) conference. Stanley considered the invitation “basically propagandistic,” but thought that the United States had to accept it because of Western Europe’s interest in détente. Moreover, while he saw possible gains for the West in Eastern Europe emerging from such a conference, NATO could not let its guard down—the military balance as it existed had to be maintained. As usual in most ACUS publications, Stanley warned about the dangers of the Mansfield (Senator Mike Mansfield (D-MT)) Amendment that called for cutbacks in US ground forces in Europe.

That same year, along with the Atlantic Institute and CAEC, ACUS sponsored the publication of “The Multinational Corporation in the World Economy.” Treasury Secretary David Kennedy wrote the introduction to the proceedings of a 1969 conference that dealt with encouraging foreign investment in the US and Canadian economies. Among those attending were business leaders from North American and West European countries and Japan, and Secretary of State William Rogers, Secretary of Commerce Maurice Stans, and Arthur Burns, President Nixon’s chief economic advisor. The participation of Japan in the conference was unique. ACUS prided itself in being one of the first Atlantic organizations to try to integrate Japan into the Western alliance—the Japanese liked the “idea of dialogue” that went into off-the-record discussions that resulted in an on-the-record publication.

The Japanese also participated in an environmental conference supported by the Council and the Battelle Memorial Institute, where the ubiquitous James Huntley would soon work, held at the State Department in January 1971. The State Department often provided a venue for ACUS meetings, including the annual spring conferences for NATO officials, board members, and academic associates. The proceedings of the 1971 environmental conference were published later that year in “Managing the Environment.”

Designating the environment a “new priority,” the editors called for huge “warlike” expenditures to improve the quality of life. To this end, the West needed to develop an International Ecological Institute, with business and government joining together to resolve the problems of air and water pollution. As usual, most of those attending the conference and writing the sections of the report adopted a moderate position, and were careful to gently prod the business community to cooperate internationally for everyone’s financial and personal health.

In 1972, ACUS sponsored a different sort of book, International Economic Peacekeeping in Phase II, in which Harald B. Malgren consulted with Council officials but, in effect, wrote his own monograph. Malgren, who had worked on the President’s Advisory Council on Executive Organization and later in the year was appointed Deputy Special Representative for Trade Negotiations, dealt with conditions created by the Nixon administration’s dramatic nationalist August 15, 1971 reorientation of domestic and international economic policies. Calling attention to the “growing world economic interdependence,” he recommended a variety of modest institutional changes in the US government that would make the coordination of economic policy easier. Responding to those on the left, he contended that until recently, economic factors had always received short shrift from foreign-policy decision-makers.

Returning to détente in 1973, ACUS produced a slim volume based on the prospects for the CSCE, which had begun in Helsinki in 1972, and Mutual and Balanced Forced Reduction (MBFR) talks, which had begun in Vienna earlier in 1973. Among the five editors of Era of Negotiations was James Sattler, who was deputy project director under Joseph Harned. Whatever Sattler’s influence, the final product looked like most other ACUS products: cautious approval of détente, a fear of the Finlandization of Europe, concern about Ostpolitik of the Germans and its possible impact on NATO force levels, and related fears that MBFR posed risks as great or “even greater” than opportunities for the West. Indeed, Sattler’s work for the Council always appeared somewhat to the right of center—he was not there to influence its product. But he did get to work with luminaries like George Ball, Zbigniew Brzezinski, Alfred Gruenther, Foy Kohler, John McCloy, and Eugene Rostow who were members of the project’s advisory committee.

Despite the tepid endorsement of Nixon’s détente policies, two members of the committee published their dissent in appendices. Achilles, who soon would become one of the founders of the Committee on the Present Danger, did not want NATO to renounce the use of force. Jay Lovestone, opposing “détente-at-all-costs,” did not want to approve a CSCE agreement that accepted Soviet imperialism. In something akin to the Supreme Court’s publication of minority opinions, most ACUS monographs soon included sections devoted to comments from study-group participants who did not agree with all the conclusions.

The year 1973 also saw ACUS sponsorship of The European Community in Perspective, a book by independent scholar Gerhard Mally, a former staffer at the Foreign Policy Research Institute. Mally sought to explain where the European Community was—an “economic giant” but still a “political dwarf”—with unity not a “fait accompli” but an “idée force,” and where it was going—a confederation by the end of the decade.

Mally’s book was one of the few published by the Council to receive scholarly attention. Elliott Goodman, the reviewer for the American Political Science Review, found it a “useful survey” but “somewhat superficial” compared to other books in the field, while F.S. Northredge in the Journal of Common Market Studies saw it as a “tedious survey,” which was “disappointingly uninquisitive.” In discussing a grant application, one scholar who found ACUS to be an “effective institution” nevertheless considered it not to be “an effective institution for original research.”

ACUS returned to its in-house, policy-oriented studies with US Agriculture in a World Context, edited by D. Gale Johnson, an economics professor from the University of Chicago, and John A. Schnittker, a former undersecretary of agriculture. Supported by a Rockefeller Foundation grant, and working closely with an ACUS Advisory Committee, the editors carefully outlined the role of US agriculture in the American and international economies and then called for trade liberalization. As in the Era of Negotiations, several advisory committee members offered gentle dissents from some of the conclusions. More important were the comments from several of the participants who pointed out that many of the dramatic economic and agricultural developments between 1972 and 1974—including the Soviet great grain robbery—took place after several sections of the book had been completed. This sort of criticism demonstrated the relative lack of utility of the book-length monograph, with its long gestation period, as compared to briefer soft-bound monographs to which ACUS began to turn more frequently. In the summer of 1975, ACUS launched its “Policy Paper” series that dealt with “policy analysis.” Some of those policy papers merely presented the conclusions of upcoming monographs, but others were addressed to immediate short-range issues and stood by themselves.

The success of the agricultural study led ACUS in 1974 to ask for more support from the Rockefeller Foundation. Describing progress made on the new grant, Francis Wilcox, who had replaced Wallace after ACUS’ first director general died in December 1974, told a Rockefeller official that he was “impressed” with the way “the Council has been able to get a great deal of work out of many responsible people at very little cost.” In another letter, Wilcox, a former dean of SAIS, boasted about the Council’s “very effective work with a very small budget.” Through the seventies, ACUS employed fewer than ten people on its full-time payroll, half of whom were support people. The seemingly bloated budget submitted to the Rockefeller Foundation for a study on the “Beyond Diplomacy” project on Intergovernmental Organization and Reorganization was $89,000, of which $47,000 involved publication costs and $19,000 consultant fees. However, the budget for the meetings of the study group itself—four meetings for twenty-five people for $1,000, and twenty-one meetings for ten people for $3,780—certainly seemed reasonable. This was a product of filling study groups with local experts who had no travel costs or board members who were wealthy enough to pay for transportation and hotel bills.

By the mid-seventies—with its journal and newsletter, relationship to and sponsorship of other Atlantic Community organizations, educational activities that promoted the Community, publications and active advisory and study groups in economic, environmental and energy, and security policy areas, and its growing interest in extra-European issues—ACUS had established an agenda that would take it to the twenty-first century. In a decade and a half, ACUS had come a long way from those chaotic early days when it had difficulty defining its mission.

ACUS impact on foreign policy

By 1975, although the growing number of ACUS books and monographs were full of useful data and were well-organized and well-written, they seldom were reviewed in scholarly journals or made much of a splash in the popular press, in part because they generally presented the same sort of common-sense, moderate, internationalist line to Cold War and economic issues.

Moreover, the publications rarely paid for themselves in terms of sales—they had to be subsidized by the Council. On occasion, board members tried to increase sales and public interest. Achilles, for one, organized campaigns around press conferences and lunches with selected journalists and government officials to little avail.

As for direct impact on policymakers, at least through the mid-seventies, archival evidence reflects generally polite interest—and little more—from high officials in the State Department and other government agencies who were sent copies of the materials. A sampling of responses from board members who were in government in the sixties and seventies range from President Gerald Ford’s contention that when he received an ACUS document he “read it, absorbed it, and benefitted from it” because he found the “information helpful,” and Al Haig’s recollection that he was an “avid reader of Council products,” to those of Robert S. McNamara, Frank Carlucci, Terrence Todman, and Helmut Sonnenfeldt, who had respect for the Council but little time to read reports from non-governmental agencies amid what Sonnenfeldt refers to as “a flood of papers” that were always on his desk at the National Security Council.

It might well be, however, that evaluations of the impact of ACUS on policy and opinion cannot be measured through the often anemic sales figures of books or the relative infrequency of bureaucrats responding in detail to ACUS reports. Joseph Harned, the Council official who organized, developed, and chaired many of the study groups that produced books and policy papers, acknowledges that most of those publications were not especially interesting—not only in hindsight, but even when they were published. He could see why government officials failed to find innovative or immediately useable strategies in ACUS reports.

But that was not the point of the study-group activity. The key for him, which had never been clearly explicated to those who took part in the activity, was the eighteen-month to two-year process of producing a final report. During that time period, government and business leaders, often younger second-tier people, got to know and understand one another, as they created permanent relationships—”backchannel networks of continuing communication”—that lasted for decades. The bringing together of small groups of leaders and future leaders who worked intimately with one another over a lengthy period of time was what was important to Harned, not the publications that of necessity had to be bland.

Considering his interpretation of the work of the Council, Harned was not concerned about the immediate impact on policy of its many studies. Moreover, there was “no way to prove the effectiveness” of the Council if its main function was to create a personal community of influentials. Thus, when foundations came around to gauge the Council’s effectiveness, Harned developed conventional indicators “out of whole cloth”—foundation officers were ultimately “ignorant of what we were about.”

If Harned is correct about the true significance of ACUS study groups and their publications—and there is no reason not to accept his insider perspective—then one can see why the East German government sent James Sattler to work there. As a consultant for the Council, he met frequently with prestigious board members, as well as with former Council members and their friends. From these interactions, according to Harned, he was able to develop “capsulized characterizations of the private, personal political views of highly-placed Americans.”

The Council might have become an even more attractive place for foreign agents in 1980 when it instituted a fellowship program that brought young officers and officials from the State Department, Defense Department, and other government agencies to spend one year with the Council, assigned to one or another of its working groups. By 1998, the Council was hosting nineteen fellows, with the program having branched out to include young officials from the Japanese Defense Agency, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Indian Army, and the Hungarian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, along with the US contingent.

From the late eighties through the nineties, the Council’s high-level policy papers, written by distinguished scholars and other experts, especially those dealing with Eastern Europe and nuclear proliferation, have occasionally made headlines and apparently influenced policymakers. In fact, recent administrations have asked ACUS officials to play important roles in working with Russians and East Europeans during this difficult transition period. But such direct impact on and relation to US policymakers did not figure prominently during the Council’s early years. Nonetheless, through its promotional work with educators and the general public and its creation of international networks of officials and businesspeople, it helped to keep Americans interested in maintaining and increasing their ties with Europe and the world beyond.

Melvin Small is a distinguished professor emeritus in the Department of History at Wayne State University. He is the author or editor of fifteen books on American foreign relations, public opinion, and international war, including Democracy and Diplomacy (1996) and At the Water’s Edge (2005).

This piece was originally published by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and is republished here with permission.

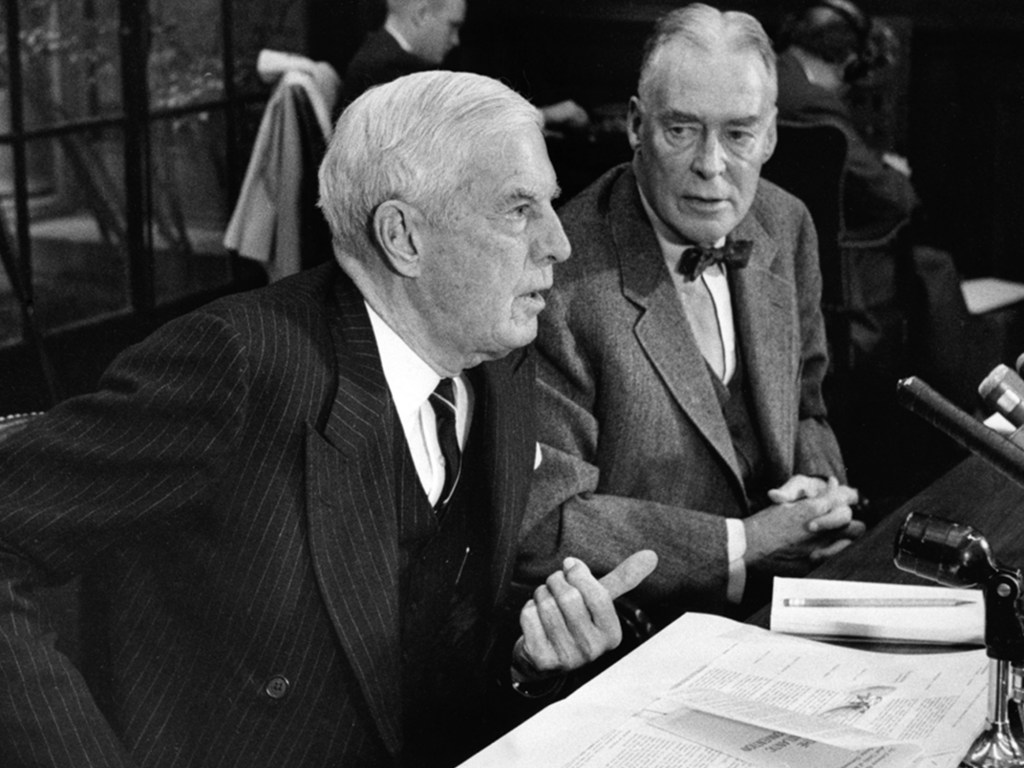

Image: Council founders Christian Herter and Will Clayton testify before Congress in 1962 about the potential expansion of NATO.