WASHINGTON—The Trump administration’s resolute handling of Venezuela—framed unapologetically in terms of strategic necessity—has once again revived an idea many Europeans hoped had been buried: that the United States should “take” Greenland.

European capitals reacted, again, in a familiar way: with statements of concern and invocations of international law. That reflex may be understandable. But it is also revealing. Because if Europe’s response to US power politics is limited to declaring what is not allowed, it should not be surprised when its voice carries little weight in the new era of transactional power politics.

Trump’s rhetoric about “taking” Greenland is neither new nor legally plausible. Greenland is an autonomous territory within the Kingdom of Denmark, embedded in NATO and protected by international law. There is no legitimate pathway for a Venezuela-style intervention in the Arctic. But legality alone does not create security. And Europe should be careful not to mistake moral clarity for strategic engagement.

The real lesson of Venezuela is that the Trump administration acts where it believes control is feasible, resistance manageable, and alternatives absent. If Europe wants to ensure that no outside power—not the United States, not Russia, not China—can credibly contemplate coercive leverage over Greenland, then it must focus less on protest and more on its own strategic steps.

Why Greenland matters

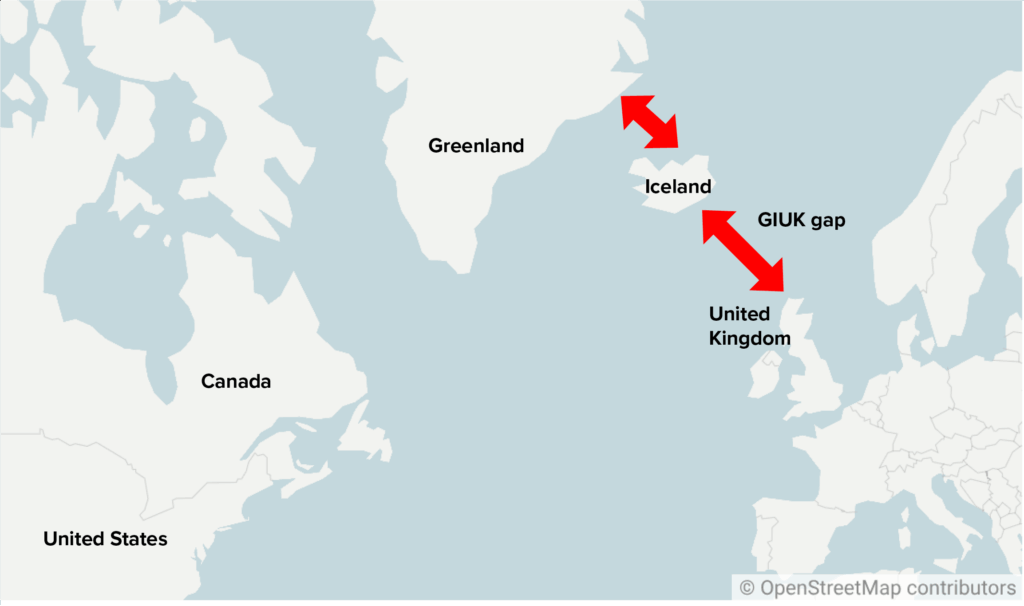

From Washington’s perspective, Greenland is a strategic asset. Its location astride the Greenland–Iceland–UK (GIUK) Gap makes it central to monitoring Russian—and, potentially, soon Chinese—submarines entering the Atlantic. Early-warning and missile-tracking radar systems stationed in Greenland feed directly into US homeland defense. Beyond that, Greenland is emerging as a critical node in satellite command and control, space domain awareness, and satellite tracking. Its geography allows for satellite ground stations and secure communications infrastructure that are increasingly vital as rivals develop counter-space and cyber capabilities.

That logic explains why in June 2025, the Trump administration shifted Greenland from US European Command to Northern Command. It reflects a broader view of the island as part of the emerging great-power contest in the Arctic—a contest in which Russia has already built a formidable Arctic military posture and China is positioning itself for long-term influence as a self-declared “near-Arctic state.” And Moscow and Beijing are increasingly cooperating on the development of the Northern Sea Route, which will allow for a shorter dual-use shipping route between Europe and Asia.

A new Arctic contest

Europe’s problem is not that Washington sees Greenland as a strategic asset. It is that Europe has largely failed to do so itself.

For decades, Greenland was treated as a political sensitivity rather than a strategic priority. That complacency is now dangerous. In an era of renewed power competition, territory that is weakly defended, lightly governed, or externally dependent invites pressure, regardless of legal status.

There are encouraging signs that this is beginning to change. European actors are investing in satellite communications infrastructure in Greenland to reduce overreliance on Norway’s Svalbard island and harden resilience against interference. Denmark is increasing Arctic defense spending and discussing the deployment of new capabilities in Greenland. These steps matter, but they remain too slow, too fragmented, and too cautious.

What Europe lacks is not awareness but resolve. If the objective is to make coercion impossible rather than merely illegal, then Europe must ensure that Greenland is visibly defended, deeply integrated into European security planning, and politically anchored in transatlantic cooperation.

Making Greenland unassailable

That means a sustained European presence capable of monitoring the GIUK gap, protecting critical and space infrastructure, and denying Russia and China the ability to encroach further on the Arctic region. This cannot be achieved through episodic engagement. It requires a calculated long-term commitment.

Paradoxically, this is also the most effective way to deal with the Trump administration. The US president is unlikely to be restrained by lectures on international law. But he does respond to strength, clarity, and facts on the ground. A Europe that treats Greenland as central to its own security, rather than as a liability to be explained away, can shift the Trump administration’s fixation on acquiring Greenland toward cooperating on Greenland’s security.