Francis Fukuyama proposed his hypothesis of an “end of history” more than thirty years ago. He argued in 1989 that, with the imminent collapse of the Soviet bloc, humanity had reached “the end point of mankind’s ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.”1Francis Fukuyama, “The End of History?,” The National Interest 16 (summer 1989), 3–18 The “third wave” of democratization appeared to vindicate Fukuyama’s argument by the end of the twentieth century. Today, however, it is by no means clear that liberal democracy is the only game in town. The number of democracies in the world has stagnated in the last two decades, and many of the countries labeled as such are experiencing clear regressions.2Global State of Democracy Report 2022: Forging Social Contracts in a Time of Discontent, International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA), 2022. Probably more worrisome, global opinion surveys show decreasing confidence in democratic institutions among the general public.3See, for example, the different waves of the World Value Survey, which show that an increasing share of the world population believes that “having a strong leader that does not have to bother with parliament and elections” is a good idea; https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org. This tendency is not only visible in developing nations, but also in the United States and Europe, the very birthplaces of modern democracy.

Democracy can (and should) be defended on ethical and moral grounds, as the system that best upholds the dignity of every citizen, based on the principles of individual freedom, equality, fairness, and justice. Nonetheless, what is in question today is not this intrinsic value of democratic institutions, but the capacity of free societies to produce sustained improvements in material well-being and overall prosperity for all. It is thus as pressing as ever to deepen our understanding of the relationship between political regimes and economic outcomes, and the mechanisms through which democracy can truly deliver. To strengthen the case for liberal democracy we must therefore look at its consequences, especially in terms of economic development and growth.

Economists have worked on this task at least since barro (1996).4Robert J. Barro, “Democracy and Growth,” Journal of Economic Growth 1, no. 1 (March 1996), 1–27 However, they have not yet reached a consensus regarding the effect of democratization on subsequent growth.5Some examples from the literature: Gerring et al. conclude that “the net effect of democracy on growth performance cross-nationally over the last five decades is negative or null,” (John Gerring, Philip Bond, William Barndt, and Carola Moreno, “Democracy and Economic Growth: A Historical Perspective,” World Politics 57, no. 3 (April 2005), 323–64). Similar conclusions can be found in Barro, “Democracy and Growth”; José Tavares and Romain Wacziarg, “How Democracy Affects Growth,” European Economic Review 45, no. 8 (August 2001), 1341–78; or Francesco Giavazzi and Guido Tabellini, “Economic and Political Liberalizations,” Journal of Monetary Economics 52, no. 7 (2005) 1297–1330. On the other hand, several works find positive effects, including: Torsten Persson and Guido Tabellini, “Democracy and Development: The Devil in the Details,” American Economic Review 96, no. 2 (May 2006), 319–24; Dani Rodrik and Romain Wacziarg, “Do Democratic Transitions Produce Bad Economic Outcomes?,” American Economic Review 95, no. 2 (May 2005), 50–55; Elias Papaioannou and Gregorios Siourounis, “Democratisation and Growth,” The Economic Journal 118, no. 532 (October 2008), 1520–51; or more recently Daron Acemoglu, Suresh Naidu, Pascual Restrepo, and James A. Robinson, “Democracy Does Cause Growth,” Journal of Political Economy 127 no. 1 (2019), 47–100. Very recent and thoughtful studies disagree on the most basic conclusion. As an example, Acemoglu et al. conclude that democratization increases GDP per capita by 20 percent in the subsequent twenty-five years, compared to non-democracies.6Acemoglu et al., “Democracy Does Cause Growth.” Instead, Coricelli et al. find that economic growth in democracies and autocracies is similar, while a third group of hybrid regimes perform significantly worse, generating a U-shaped relationship between political regimes and economic performance.7Nauro Campos, Fabrizio Coricelli, and Marco Frigerio, “DP17551-2 The Political U: New Evidence on Democracy and Income” (discussion paper 15598, Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) Press, September 29, 2022). There are different potential shortcomings of the literature that could explain the conflicting results, from measurement error to other technical econometric problems, such as omitted variable bias, unmodeled country-specific characteristics, reverse causality, and so on. All of these are relevant, but this essay will focus on a prior, foundational issue—one which is often overlooked by the empirical economics literature: the conceptualization of the variables of interest (i.e., freedom and democracy).

Previous works on the effect of democracy on growth have mostly used readily available composite indexes of democratic institutions without paying much attention to the underlying definitions embedded in them, which can vary widely.8See Coppedge et al. (2017) for a detailed comparison of democracy indexes. This is evident when we compare the two indexes most often used in the literature, produced by the Polity Project9Monty G. Marshall, Ted Robert Gurr, and Keith Jaggers, Polity IV Project: Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions, 1800-2015. Dataset Users’ Manual, Center for Systemic Peace, 2016 and Freedom House.10“Freedom in the World 2022: The Global Expansion of Authoritarian Rule,” Freedom House, accessed February 15, 2023, https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2022/global-expansion-authoritarian-rule The former is narrower, and focused tightly on two aspects of democracy: the electoral component and the constraints on the executive. The latter takes a broad view of democracy, giving a dominant weighting (60 percent of the index) to individual liberties such as freedom of religion, freedom of movement, secure property rights, and so on, all of which are absent from the Polity Index. The obvious contrast between the different measurements of democratic institutions used in analyses of the democracy-growth relationship not only casts doubts on the comparability of the different studies, (which could partly explain the inconclusive results), but also clearly points to a lack of rigorous assessment of which specific aspects of democracy matter for economic growth, and through what channels.

This paper seeks to emphasize that, in order to adequately measure how much liberal democracy affects growth, it is of crucial importance to first clearly define what it is. As the great political scientist Giovanni Sartori pointed out more than fifty years ago, “concept formation stands prior to quantification”11Giovanni Sartori, “Concept Misformation in Comparative Politics,” American Political Science Review 64 no. 4 (December 1970), 1033–53. and, we could add, both necessarily precede the assessment of the effects on other aspects of reality (economic or any other). I am by no means claiming that the endeavor of defining, conceptualizing, and identifying the necessary attributes of democracy has not been pursued before. Such a claim would obviate a whole field of political theory and philosophy going back to Plato and Aristotle! To the contrary, the suggestion of this essay is that in order to make progress on the quantification of the economic effects of liberal democracy, we need to take full stock of those theoretical investigations and open the black box of democracy, clearly linking its building blocks to sources and mechanisms that affect economic development. Thus, this essay aims to pick up the gauntlet proposed by Acemoglu et al. to study “how democracy alters economic incentives and organizations and to pinpoint what aspects of democratic institutions are more conducive to economic success,”12Acemoglu et al., “Democracy Does Cause Growth” (emphasis added).

When we think about free and democratic societies, we have in mind much more than just countries in which government officials are appointed by some kind of electoral mechanism. We implicitly include neighboring concepts such as the rule of law, separation of powers, or a battery of individual rights (political, civil, economic, etc.). The interconnection of these concepts is clear, but the boundaries between them are fuzzy, and the definitions often overlap. It is not straightforward to decide how different aspects of free societies should be delineated, which attributes are necessary, or how the different pieces interact.

The Freedom Index, proposed recently by the Atlantic Council’s Freedom and Prosperity Center (FPC), constitutes an appealing contribution to the debate. The Index is constructed around a comprehensive view of freedom, which tries to capture all the different ingredients that make up a free society. In particular, the Index is built out of three separate components: legal, economic, and political freedom (with legal freedom roughly analogous to the rule of law). Each of the three components is further divided into several sub-components, but this essay will only deal with the three primary components. The rationale for considering three separate components of freedom is that not all democracies are the same—and neither are all autocracies alike. By disaggregating freedom in this way, and analyzing separately these three dimensions of freedom, we may better capture the mechanisms through which different attributes of the institutional architecture of a country affect its economic performance.

The FPC proposal generates two preliminary questions: (a) Are the proposed components of freedom theoretically well-grounded?; and if so: (b) Are they empirically relevant? This essay tries to answer the first by reviewing the definitions offered in the academic literature on the rule of law, democracy, and economic freedom, before sketching a framework to jointly think about all three concepts. Regarding the second question, we go on to provide a first test of the empirical relevance of the proposed structure by analyzing the situation of suitable empirical counterparts for the three concepts, considering today’s situation among developing nations. Finally, we conclude by presenting some research ideas to deepen our understanding of the link between the institutions of free societies and economic development.

A review of conceptualizations

Legal scholars, political scientists, and economists have proposed a variety of definitions for each of our concepts of interest: democracy, rule of law, and economic freedom. The common notion of “essentially contested concepts” certainly applies to all three. In general, it is possible to start from a minimalist (narrow or “thin”) definition of each concept, which we gradually extend with additional attributes until we arrive at a maximalist (broad or “thick”) description. As we will see, more extensive definitions of one concept are likely to overlap with one or both of the other two. In the following sub-sections, I briefly review the most relevant conceptualizations of the three dimensions of freedom.

Rule of law

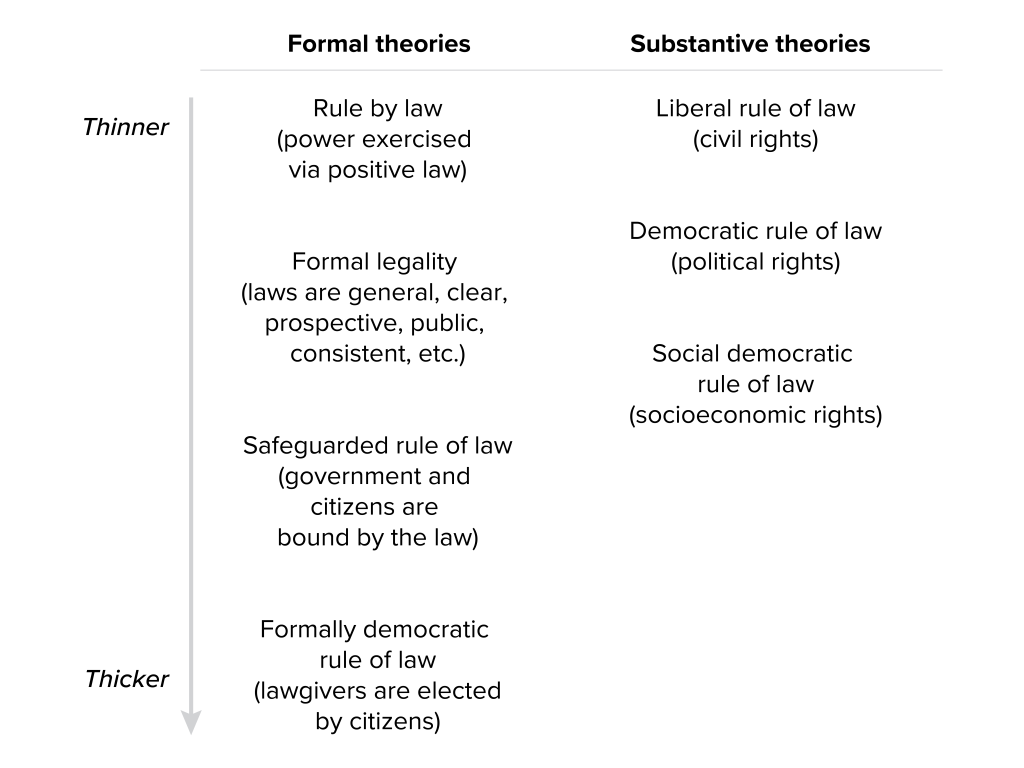

The rule of law is a political ideal about the legal system, and thus about the laws and their characteristics. A standard approach to systematizing different conceptions of the rule of law is to differentiate between formal requirements that the laws must possess, and characteristics that deal with the specific content of those laws. This distinction gives rise to what are usually labeled as “formal” and “substantive” formulations of the rule of law. Even within these two traditions, a variety of conceptualizations has been proposed in the literature, depending on the attributes required by different authors, in considering whether a legal system abides by the rule of law. Following Tamanaha13Brian Z. Tamanaha, On the Rule of Law: History, Politics, Theory (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004). and Møller and Skaaning,14Jørgen Møller and Svend-Erik Skaaning, “Systematizing Thin and Thick Conceptions of the Rule of Law,” Justice System Journal 33, no. 2 (2012), 136–53. Figure 1 depicts a schematic hierarchy of rule-of-law conceptualizations. As we move down each column, additional attributes are included in the concept and the definition becomes thicker.

Figure 1. Rule of law conceptualizations

Starting with formal theories (left), a minimalist definition of rule of law only imposes that the exercise of power by the state is carried out via positive legal norms. That is, as long as all actions of government officials are authorized by law, we could say such a state fulfils the requirements of the rule of law. The literature has tended to denote such a situation as mere rule by law, and pointed to an obvious flaw which makes it virtually useless: almost any state in the world today operates, at least de jure, through legal norms and decrees. A thicker version of the rule of law imposes certain formal criteria on the laws, which pivot around the idea of “universalizability.” This characterization of rule of law, usually denoted as “formal legality”, requires that government laws are general, publicly promulgated, non-retroactive, clear, consistent, and relatively stable. Similar lists of formal standards can be found in a variety of authors, especially prominent legal scholars such as Fuller,15Lon L. Fuller, The Morality of Law: Revised Edition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1969). Raz,16Joseph Raz, The Authority of Law: Essays on Law and Morality (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979). or Finnis.17John Finnis, Natural Law and Natural Rights (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1980). These necessary formal traits are required for laws to serve their basic function: to guide behavior of those subject to them. Intuitively, it is not possible for individuals to abide by the law if it is not public, or contradicts another norm, or is unintelligible, etc.

Now, a clear question emerges: Should laws bind only regular citizens, or also the government and its officials? This is a crucial element that not every author has solved successfully. Hobbes, in Leviathan, argues that the sovereign is not bound by the laws he himself promulgates, as “he that is bound to himself only is not bound.”18Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, or, The Matter, Forme, and Power of a Common-wealth Ecclesiasticall and Civill (1651). The classical liberal solution of philosophers such as Montesquieu and the US Founding Fathers is to break up “the sovereign” into different branches, in particular separating the judicial arm of the state from the executive power, allowing the former to guarantee that the actions of the latter comply with the established law. The contemporary legal theorists named above agree that for a political system to fulfil the rule of law, the government and state apparatus should be subject to the legal system, and include conditions to ensure this is the case. Raz further stipulates that, for a state to be considered as following the rule of law, it must guarantee an independent judiciary with review powers, and prevent the discretion of crime-preventing agencies from perverting the law. Fuller and Finnis reach a similar conclusion to Raz, requiring that government actions are congruent with declared rules, and public officials are responsible and accountable for compliance with the laws. Tamanaha19Brian Z. Tamanaha, “The History and Elements of the Rule of Law,” Singapore Journal of Legal Studies, (December 2012), 232–47. gives a very simple and intuitive definition that synthetizes what Figure 1 denotes as “safeguarded rule of law.” He states that “the rule of law means that citizens and government officials are bound and abide by the law.”

The last attribute included in the formal theories of Figure 1 deals with the source of rules, that is, how rules are created, and by whom. This democratic requirement is rather different to the attributes discussed above—which all deal with general characteristics of the law—and thus does not seem to fit perfectly within formal definitions of rule of law. The addition to those definitions of a democratic source of the law only makes sense if we understand democracy in purely procedural terms; that is, something in line with the minimalist definition of democracy given by Schumpeter as a modus procedendi, by which lawgivers and government agents who apply those laws are selected “by means of a competitive struggle for people’s vote.”20Joseph Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1942; 4th ed. reprint 1974).

The right column of Figure 1 summarizes substantive versions of the rule of law. They differ in the specific content that they require for a legal system to fulfil the ideal of rule of law. That is, these versions add to formal versions some necessary substantive content related to the recognition of individual or collective rights. Bingham is a clear exponent of this conception,21Tom Bingham, The Rule of Law (London: Allen Lane, 2010). but we could also include legal theorists such as Dworkin or Hart. The thinnest substantive version of rule of law would include fundamental human rights, especially those related to the judicial process. In a second step, negative liberal rights are added. These are individual civil rights, clearly envisioned to limit the scope of governmental action, generating a sphere of autonomy for the individual, free from state intervention. While liberal rights—such as freedom of expression, movement, religious freedom—are uncontroversial, others might not be accepted by all. A clear case is that of private property rights. Some classical liberal philosophers such as Locke, and recent legal scholars such as Ronald Cass, would argue that property rights are inalienable individual rights equivalent to the others mentioned above, inextricably linking the rule of law with the legal definition and protection of property rights.

Those favoring the thicker substantive version of the rule of law, which includes socioeconomic positive rights, would certainly disagree. Second-generation rights, as they are sometimes called, would constitute an additional bundle of individual freedoms that would be required in even thicker conceptions of the rule of law. These are rights intimately linked to the democratic political process, such as freedom of association, demonstration, and active and passive suffrage. For this reason, some authors see the electoral component as part of this version of rule of law, and not as the last attribute of formal conceptualizations. In any case, it is clear by now how substantive thick conceptions of the rule of law begin to overlap with the neighboring concept of democracy. The thickest version of the idea of rule of law includes socioeconomic rights.

Third-generation rights are fundamentally different from those mentioned above. These are positive social rights which do not force the political power to abstain from intervention. To the contrary, socioeconomic rights typically compel the government to actively provide individuals with certain basic needs such as education, a social safety net, healthcare, etc. A clear issue arises when trying to organize the different sets of rights to come up with a hierarchical order of substantive versions of the rule of law. A particular problem is whether individual civil liberties should be placed before or after political rights. If we look at the historical political development of the Western world, we would favor the order presented in Figure 1, where the recognition of civil rights precedes political rights. Instead, in many developing countries today it would seem that political rights are more generally operative than individual freedoms. This is also in line with the systematic review of the concept of democracy, to which I turn in the following section.

Democracy

The electoral component is at the core of any definition of democracy. A basic democratic requisite is that those holding political power have been appointed by citizens through some kind of voting mechanism. It is the ideal of “self-rule” or “rule by the people,” that generates a continuing responsiveness of the government to the preferences of its citizens.22Robert A. Dahl, Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1971). It is not only those who apply the law that are elected by citizens, but also those who make the law. Thus, the source of law is the sovereignty of the people, introducing an element of consent on the legal system and for the exercise of power, absent from autocratic systems.

Now, this is the democratic ideal. In real modern societies, what attributes are necessary if we are to label a country as democratic? As would be expected, there is no clear consensus among political scientists and philosophers. The task of organizing the different conceptions might be easier than with the concept of rule of law, because in the case of democracy the hierarchical ladder of abstraction has a clear starting point (the electoral core), and more extensive definitions require the addition of attributes that better guarantee the effectiveness of that core. Thus, the controversy among scholars is about where to draw the line to consider a given system as democratic, rather than on the categorized order of types.

A minimalist definition of democracy focused on electoral principle is given by Schumpeter, as “the institutional arrangement for arriving at political decisions in which individuals acquire the power to decide by means of a competitive struggle for the people’s vote.”23Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. The crucial aspect of this definition is competition, the fact that different groups are allowed to enter a contest to gain people’s support. Schumpeter does not require that such a contest be fully free, fair, and inclusive, in the sense that all citizens (or a large majority of them) are allowed to participate and freely express their preferences. The definition imposes some degree of competition for political support, and thus even electoral systems with moderate defects could be categorized as democracies. More demanding conditions on the electoral core—in terms of freer and relatively inclusive elections—situate us closer to the definitions of democracy of authors like Przeworski24Adam Przeworski, Democracy and the Market: Political and Economic Reforms in Eastern Europe and Latin America (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991). or Vanhannen.25Tatu Vanhanen, The Emergence of Democracy: A Comparative Study of 119 States, 1850–1979, (Helsinki: The Finnish Society of Sciences and Letters, 1984). These definitions are still mainly procedural, and do not involve any systematic protection of individual rights besides a relatively ample suffrage. In particular, rights such as freedom of assembly or freedom of speech—rights that directly favor practical electoral competition—are not specifically protected. Intuitively, democracy is understood as “a system in which governments lose elections.”26Przeworski, Democracy and the Market. A system of general, free, and fair elections, that is decisive in the choice of political leaders but lacks an adequate protection and respect for individual rights, has been denoted as “electoral democracy”27Tatu Vanhanen, The Emergence of Democracy: A Comparative Study of 119 States, 1850–1979 (Helsinki: Societas Scientiarum Fennica, 1984) or “illiberal democracy.”28Fareed Zakaria, Fareed. The Future of Freedom: Illiberal Democracy at Home and Abroad (New York: Norton, 2003)

Thicker definitions of democracy add individual rights and guarantees to the electoral core described above. We can think of individual rights as serving two purposes in relation to democracy. On one hand, political rights significantly improve the electoral mechanism and thus the identification of those in power and the policies they enact with the population they govern. On the other, civil or liberal rights serve as a limit to the majority principle embedded in the democratic process. Including different sets of these rights generates the two thicker conceptualizations of democracy generally referred to in the literature. Probably the most widely accepted definition of democracy is that of Robert Dahl.29Dahl, Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition. If governments are to be responsive to their peoples, Dahl argues, then citizens must have effective opportunities to formulate, signify, and have those preferences weighted equally. In Dahl’s view, such opportunities not only require free and fair elections but a series of guarantees in the form of individual political liberties. In particular, he enumerates eight guaranteed liberties: (1) freedom to form and join organizations, (2) freedom of expression, (3) right to vote, (4) eligibility for public office, (5) right of political leaders to compete for support/votes, (6) alternative sources of information, (7) free and fair elections, and (8) institutions for making government policies depend on votes. The individual rights contained in guarantees 1, 2, 3 and 6 are eminently political, in the sense that they are considered here as instrumental for the electoral political process. Dahl denotes a system that safeguards free and fair elections through a general respect for political liberties as “polyarchy.”

We can better understand the difference between “electoral democracies” and Dahl’s polyarchies through the ideas of contestation and inclusiveness. Electoral democracies require a significant degree of inclusiveness, as epitomized by the extension of the franchise to large fractions of the population, but are less demanding in terms of the degree of allowed public contestation. Polyarchies require both ample suffrage and opportunities to oppose, contest, and compete in the political arena—qualities that are only effectively attained if political rights are sufficiently protected.

Finally, the thickest definition of democracy incorporates liberal civil rights. As already mentioned in the discussion about the rule of law, these rights serve a different purpose from political rights. The primary objective of liberal civil rights is to limit the scope of governmental action, and by doing so guarantee an area of individual autonomy and freedom; this applies to both autocratic or democratically elected governments. In the latter case, individual liberal rights limit the risk of the tyranny of the majority. It is important to notice that authors that propose this thick conceptualization of democracy, incorporating political and civil rights, usually assume an independent judiciary capable of enforcing such rights. Thus, an all-embracing definition of “liberal democracy” subsumes the idea of safeguarded rule of law discussed above (see O’Donnell for examples30Guillermo O’Donnell, “Polyarchies and the (Un)rule of Law in Latin America: A Partial Conclusion” in The (Un)rule of Law and the Underprivileged in Latin America, eds. Juan E. Méndez, Guillermo O’Donnell, and Paulo Sérgio Pinherio, (Notre Dame: Notre Dame University Press, 1999), 303–37; and Guillermo O’Donnell, “Human Development, Human Rights, and Democracy,” in The Quality of Democracy: Theory and Applications, eds. Guillermo O’Donnell, Jorge V. Cullell, and Osvaldo M. Iazzetta (Notre Dame: Notre Dame University Press, 2004), 9–92.). It is clear that the hierarchy of democracy types sketched here visibly resembles the outline of the different substantive conceptions of rule of law, showing again the difficulty of disentangling these concepts.

Economic freedom

Economic freedom is a concept clearly associated with economists such as Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek, but we can trace its origins to the classical liberal thinkers of earlier centuries. This is because, for many of them, private property rights were just one among many civil liberties. Thus, the theoretical rationale for economic freedom is similar to that of other liberal freedoms such as expression, movement, or religion, and is based on the principle of personal individual choice. In this way, economic freedom is viewed as a negative right that requires others (especially the government) to abstain from interference. That is, economic freedom implies absence of coercion in the sphere of economic decisions. Understood in this way, it is not possible to discern a hierarchical structure of economic freedom definitions, starting from a minimalist definition and subsequently adding attributes in order to form thicker versions of the concept, as we were able to do with the concepts of rule of law and democracy. Conceptualizing economic freedom as a dichotomous attribute that societies may possess or not is not a convincing solution either. It seems that the way to make progress is to think about economic freedom as a continuum between two polar cases, along which societies are situated. This is how modern thinkers and pundits of economic freedom like Hayek, Mises or Friedman have understood the concept. Moreover, this is also the theoretical foundation behind the construction of the two most widely used indexes of economic freedom; namely, the Economic Freedom of the World Index produced by the Fraser Institute,31“Economic Freedom,” Fraser Institute, January 26, 2023, https://www.fraserinstitute.org/studies/economic-freedom and the Heritage Foundation’s Economic Freedom Index.32“2022 Index of Economic Freedom,” Heritage Foundation, accessed February 15, 2023, https://indexdotnet.azurewebsites.net/index.

According to Friedman, the crucial issue is whether economic decisions are guided by the market principle or the political principle. The former relies on individual choice, voluntary exchange, and free competition. The latter instead relies on the coercive power of the state to decide on economic affairs. Notice that both principles are compatible with any kind of political system, whether democratic or not. Hayek would use the distinction between decentralized and centralized economies, again referring to the source of economic decisions: private individuals or the government. On one hand, the polar case in which a society is fully free in economic terms would be identified with the anarcho-capitalist views of authors like Rothbard, where all economic decisions are in the hands of private individuals, and the state has no role.33Murray N. Rothbard, Man, Economy, and State: A Treatise on Economic Principles (Princeton: Van Nostrand, 1962). On the other hand, a society in which the state owns all the means of production (even labor) and centrally decides all economic affairs would be denoted as completely unfree in economic terms. Both extreme cases are hardly empirically relevant. If we want to apply the concept to modern economies, we need first to acknowledge that these are extremely complex machineries composed of a myriad of sectors and markets, and the involvement or intervention of the state in each of them might differ widely, or even be unavoidable in some cases. As is recognized by some of the most ardent promoters of economic freedom, there are areas in which government action is necessary to generate the conditions for the full exercise of individual economic freedom. Here, the government’s protection of property rights plays a crucial role, not only requiring the recognition of private ownership and the bundle of rights associated with it, but also the enforcement of private contracts that formalize economic activities. Both economic freedom indexes mentioned above admit this necessary involvement of the state in economic affairs as a precondition for individual private action and choice, and include in their measurements of economic freedom a metric that captures the degree to which governments are capable of generating such conditions.

Notwithstanding the previous discussion, the bulk of the theoretical concept of economic freedom deals with the activities from which governments should refrain. Generally, we can think of government intervention in economic affairs in two distinct ways: regulation and taxation. Regulations limit the full exercise of the rights derived from private ownership by restricting certain activities or imposing additional requirements on private economic relationships. Taxation directly extracts resources from private individuals and places them under public administration. Both cases generate distortions in the functioning of the market mechanism by affecting relative prices and/or quantities. Given the difficulty in assessing the degree of governmental intervention through regulation in all sectors and activities of modern economies, the literature has focused on just a few especially relevant markets. In particular, both the Fraser Institute and Heritage Foundation indexes give prominent importance to the level of public regulation of international trade and investment, labor markets, and financial markets. Considering countries that have less restrictive regulations in these areas to be more economically free is not controversial. However, there is much less of a consensus when it comes to assessing the value of government taxation and how it relates to economic freedom. The two indexes mentioned both include metrics that capture the fiscal size of government, and give this a significant weight (20 percent for the Fraser index, 25 percent for the Heritage index). Government taxation, these organisations argue, reduces the resources available to private individuals to allocate and distorts relative prices and thus the functioning of the market mechanism. As a consequence, higher levels of overall taxation are assumed to reduce economic freedom.

The opposition to this view is usually based on an empirical regularity. When we look at the disaggregated data provided by economic freedom indexes, government size is positively correlated with the rest of the metrics (market institutions and regulations). That is, we observe that countries with high economic freedom scores—in terms of low market regulations and high protection of property rights—usually present relatively large governments in fiscal terms. Given this evidence, the question posed by Leschke34Martin Leschke, “Constitutional Choice and Prosperity: A Factor Analysis,” Constitutional Political Economy 11, no. 3 (2000), 265–79. or Ott,35Jan Ott, “Leave Size of Government Out of the Measurement of Economic Freedom—Put Quality of Government In,” Econ Journal Watch 19, no. 1 (March 2022), 58–64. among others, is whether government size is a useful metric for measuring the concept of economic freedom at all, or whether it should be simply removed. The discussion has one aspect that is worth examining. The removal of government size from the conceptualization of economic freedom is based on the idea that at least some fiscal activities carried out by the government can foster economic freedom (besides those already mentioned: securing property rights and the functioning of markets). That is, government taxes and spending can generate economic opportunities for some individuals. This argument resembles a positive conception of freedom as the capability to choose, epitomized by the writings of Amartya Sen. The problematic aspect of this view is that it radically contradicts the premise of the overall idea of economic freedom, which is based on a negative conception of freedom as absence of coercion. If the argument—that government size can be ignored in the measurement of economic freedom—is accepted, then the same logic would require that we dismiss other areas of the concept, such as tariffs on international trade, taxes on financial transactions, or specific government regulations that may be considered as opportunity enhancing for some individuals. It would seem that what is behind the rejection of including government size in a measure of economic freedom is to purge the concept of public interventions that are viewed as desirable, efficient, or positive. So, economic freedom would only be hampered by undesirable government interventions, however these can be identified. But then we would be trying to conceptualize a very different object. Not to what extent economic activity is guided by free individual choices and the market mechanism, but whether government interventions can improve economic outcomes. The fact that authors such as Friedman and Hayek believed that less government involvement in the economy was the surest path to sustained economic growth and prosperity is ultimately a hypothesis that must be empirically settled, but clearly does not invalidate the formative construction of the concept. Consequently, government size appears to fit well in a conception of economic freedom based on the idea of negative liberty applied to economic aspects of life.

A framework on freedom dimensions

Having reviewed, even if succinctly, the wide variety of conceptualizations proposed by the literature on our three dimensions of freedom, the natural next step is to decide which specific definition to pick. That is, where do we draw the boundaries of each concept? And, even more importantly, how do we justify our choices? Here, it is important to recall that the hypothesis proposed in the introduction of this essay is that we can better understand the relation between liberal democracy and economic performance if we dig deeper into the constitutive attributes of free societies. Therefore, the guiding principle for our delineation of concepts should be functional, aimed at isolating the mechanisms that link each dimension to economic outcomes. Ideally, we would want to define each concept so that none of them implies or requires the others, and are therefore as independent as possible. This does not imply that all three concepts are completely disconnected, or that our framework should eliminate any interaction among them. To the contrary, such linkages and interactions are at the core of the analysis proposed in this essay. Independence is understood here as the possibility, at least at a theoretical level, that a society may possess any degree of freedom in one dimension irrespective of the other two, that is, we want definitions that allow a country to have any combination of scores for each of the concepts. Finally, we need to keep in mind that the ultimate goal is to take the theoretical framework to the data, and therefore our choice of definitions should try to be empirically relevant.

When analyzing the economic effects of the rule of law, economists have usually identified the concept with the safeguarding of property rights, especially against government expropriation. Obviously, this generates an overlap with a fundamental aspect of economic freedom. Nonetheless, the implicit function given to the rule of law in such a conception provides a clear insight: the economic effects of the rule of law are related to the idea of certainty. If laws are clear, general, stable, etc., and citizens and governments generally follow them, then everyone knows what to expect, and individuals can form rational expectations about the potential consequences of their actions and decisions (economic or else). This is exactly what Hayek alludes to when he provides his idea of the concept:

Stripped of all technicalities, [the rule of law] means that government in all its actions is bound by rules fixed and announced beforehand—rules which make it possible to foresee with fair certainty how the authority will use its coercive powers in given circumstances, and to plan one’s individual affairs on the basis of this knowledge.36Friedrich A. Hayek, The Road to Serfdom (London: Routledge, 1944).

It is clear that this uncertainty-reducing function of the rule of law operates regardless of the specific political system in place. That is, the rule of law implies that the law is followed, not that the law is good. Raz, who begins his discussion about the ideal of rule of law precisely with Hayek’s quote, is very plain in this respect when he asserts that “the law can violate people’s dignity in many ways. Observing the rule of law by no means guarantees that such violations do not occur.37Raz, The Authority of Law. The specific content of the laws that individuals can expect to be applied will be included in the other two dimensions of freedom. Excluding the formal democratic principle in our rule-of-law definition allows for the possibility that autocracies may abide by the rule of law and, conversely, that democracies may fail to establish the rule of law. Both are situations that are empirically relevant if we look at the world today, strengthening the prospect that such formal definition of the rule of law can have strong explanatory power.

As we said in the previous section, the essence of democracy is that it is a political system in which governments are responsive to the citizens’ demands. The more inclusive a system, and the more it allows for citizens to oppose and contest those in power, the more closely its public policies are expected to reflect the preferences of a majority of the population. Now, how does the democratic principle affect economic outcomes? It clearly depends on the economic and social environment or, using a term commonly employed among political scientists, the cleavages present in a specific society.

In this regard, distributive aspects have been identified by economists as key factors affecting the relationship between democratic politics and economic performance—in particular, the level of inequality in terms of wealth, productive assets (land, capital, etc.), or income. The general intuition is that, if fiscal policy is decided democratically, higher levels of inequality should generate stronger pressures for redistributive taxation. Nonetheless, the empirical evidence around the distributive aspect is not generally conclusive. Furthermore, it is not even clear whether higher levels of taxation reduce or enhance economic growth. On one hand, higher taxes introduce distortionary costs and may reduce the incentives to work and invest, thus hampering economic growth. On the other, in the presence of credit or insurance market frictions, redistributive taxation may produce higher growth if it removes barriers that generate underinvestment in some sectors or activities. We can think of several other aspects that link the degree to which government policies reflect citizens’ preferences to economic results (public goods provision, publicly provided private goods such as education and health, public debt management, etc.). Given that we have defined the rule of law in purely formal terms, the democratic dimension of freedom can subsume the different sets of individual rights discussed above. Consequently, we can include both political and civil rights in our definition of democracy, only excluding property rights from the latter, as these will be taken care of as part of “economic freedom.” In this way, the boundaries between rule of law and democracy are well defined, and again we can at least theoretically envision any possible combination among them.

Finally, the definition of economic freedom in the terms described above does not present any overlap with the chosen conceptualizations of rule of law and democracy. The link between economic freedom and economic growth is created by the incentives and opportunities to invest, trade, start a business, and carry out any other economic activity in an environment of (as perfect as possible) market competition. Again, it is important to recall that any degree of economic freedom is compatible with any combination of rule of law and democracy as defined above. For example, we can imagine a dictatorship in which democracy is absent and that generally abides by the rule of law, with the highest degree of economic freedom (e.g., Singapore), or a full democracy with a strong rule of law that scores poorly in economic freedom (e.g., France).

Overall, the framework sketched in this section is in line with the one proposed by the Atlantic Council’s Freedom and Prosperity Center, and conveys similar intuitions. In particular, the idea that the rule of law is a precondition for the other two freedoms is adequately captured by the formal definition chosen. Notice that, in a society where citizens and governments do not generally abide by the law, the substantive content embedded in the legal system becomes irrelevant. That is, a society that has not secured a sufficient level of rule of law cannot de facto defend fundamental or property rights, nor will it translate its citizens’ demands effectively through the democratic process, even if these features are consecrated de jure in a written norm or constitution.

Empirical relevance of the conceptualization

The conceptualization developed in the previous section would be a futile theoretical disquisition if the empirical counterparts of those concepts (rule of law, democracy, and economic freedom) were all highly correlated across countries. That is, when we look at the data, do we observe countries systematically obtaining high/low scores in all three dimensions? If that were the case, then differentiating among dimensions of freedom would not be helpful in order to shed light on the liberal democracy-growth nexus. Instead, if the three dimensions of freedom do not necessarily move together, and we observe countries scoring high in one aspect while low in others, then it might be worth exploring in more depth the combinations of our concepts that are more likely to produce good economic outcomes. This section carries out a first test of the usefulness of the proposed framework by assessing the empirical variability observed across countries in terms of the three different dimensions.

There is a wide variety of indexes created by academics, research centers, think tanks, international organizations, and others that include our three concepts of interest. Each index implicitly or explicitly assumes a specific definition of the concept at hand. Thus, the decision about which indexes to use is not trivial. For the exploratory purposes of this essay, I will choose indexes that: are readily available; are as close as possible to the preferred conceptualizations of each concept discussed above; and that provide ample global coverage, especially for developing and less developed countries.

Regarding the rule of law measure, I rely on the V-Dem project database, which includes a rule-of-law index that is very close to the safeguarded rule of law conceptualization of Raz or Tamanaha discussed before.“38Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem),” accessed March 13, 2023, https://www.v-dem.net. In particular, it includes variables that measure the degree of predictability of the laws (formal legality), as well as indicators that measure the independence and impartiality of the judicial system, whether the executive power complies with the judiciary, the rigor and impartiality of public officials in the application of the law, and a series of indicators that measure the degree of corruption in the public sector. It is worth noting that the V-Dem index does not measure any substantive content in the form of individual rights of any kind, nor whether the source of the laws is democratic or not. The index is continuous, and normalized for the interval [0,1], with 1 denoting the highest adherence to the rule-of-law ideal.

The main objective of the empirical exercise presented below is to assess whether democracies and autocracies present substantial variability in the rule of law and economic freedom dimensions. Thus, it seems natural to use a dichotomous measure of democracy that allows clear differentiation between both groups. Among such measures, the closest to Dahl’s conceptualization (with ample coverage across countries) is provided by the Lexical Index of Electoral Democracy (LIED).39Svend-Erik Skaaning, John Gerring, and Henrikas Bartusevicius, “A Lexicial Index of Electoral Democracy,” LIED, Harvard Dataverse, 2015, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/29106. It is an ordinal index with eight levels (from zero to seven), in which the highest category is attained when a country satisfies all of Dahl’s polyarchy attributes. The previous level (six), is similar to the electoral democracy conceptualization of Przeworski or Vanhannen, that is, a country in which meaningful competitive elections with ample suffrage are present, but political rights are not sufficiently protected.

Finally, the most widely used index on economic freedom is the one created by the Fraser Institute.40https://www.fraserinstitute.org/studies/economic-freedom. This index is composed of five major areas: size of government, legal system and property rights, sound money, trade freedom, and regulation. As discussed above, there is some debate about whether all these areas should be included in an index of economic freedom, and it is certainly worthwhile to explore how alternative constructions relate to the rule of law and democracy, but such an exercise is left for future research. For the purposes of this essay, I will only slightly modify Fraser’s second area (legal system and property rights), as it includes a series of sub-components related to the independence and impartiality of the judiciary that are already measured in the rule-of-law indicator. For this reason I will recalculate this area of the index, keeping only the sub-components on “protection of property rights” and “enforcement of contracts.” The rest of the areas are not affected, and the overall index construction follows the same methodology as the original version.

The total sample, for which data are available for our three variables, covers 123 countries. These are all countries with avail-able data, excluding OECD members. Among them, in 2020 a total of sixty-four countries were classified as electoral democracies according to LIED, and fifty-nine as non-democracies (or autocracies). For the rule of law and economic freedom measures, country averages for the period 2015–2020 are calculated. Thus, we have a cross-section of countries that allows us to compare the levels of our indicators for rule of law and economic freedom, discriminating by the democracy-autocracy categorization. The results are depicted in Figure 2. White circles represent countries classified as electoral democracies, while black ones as non-democracies. Dotted lines mark the average levels of economic freedom (horizontal) and rule of law (vertical) across the full sample. This simple plot conveys a series of interesting insights. First, there is ample variability in both dimensions, for the full sample and also within the sub-samples of democracies and autocracies. This is especially apparent in the rule-of-law variable, which covers almost the full range [0,1]. Focusing on this variable, the picture clearly reflects the positive correlation between rule of law and democracy. A majority of democracies score above average on rule of law, while a majority of autocracies have below average scores. This is not surprising given the expected reinforcing effect of democratic consent from citizens, and the additional controls on the executive represented by the legislative branch and the press in a democratic system. Nonetheless, we still observe a significant number of democracies scoring below the all-country average in the rule-of-law indicator: eighteen countries in total, which equates to 28 percent of all democracies in the sample. Conversely, fourteen autocracies have above average values for rule of law, almost a quarter of all autocracies. Second, when looking at the distribution of economic freedom scores, we also observe significant dispersion, and smaller systematic differences between democracies and autocracies. The average level of economic freedom is only slightly higher among democracies (0.678), than among non-democracies (0.590). The results show that a significant share of democracies have levels of economic freedom below the sample average (36 percent), and more than 40 percent of autocracies have above average scores. Finally, looking at the joint distribution of rule of law and economic freedom further confirms that all three dimensions of freedom are far from moving together. Half of the countries labeled as democracies have below average scores on at least one of the other two dimensions, and 47 percent of autocracies present above average scores for either rule of law or economic freedom.

Sources: “Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem),” accessed March 13, 2023, https://www.v-dem.net; Svend-Erik Skaaning, John Gerring, and Henrikas Bartusevicius, “A Lexicial Index of Electoral Democracy,” (LIED), Harvard Dataverse, 2015, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/29106; “Economic Freedom,” Fraser Institute, January 26, 2023, https://www.fraserinstitute.org/studies/economic-freedom.

Conclusions

Even if merely descriptive of the current situation, the results presented in the simple exercise of the previous section suggest that the differentiation between rule of law, democracy, and economic freedom proposed in this essay can be a promising avenue for future research. Intuitively, it is likely that a full panel analysis that considers the development of these variables across time may generate even more variability. Consequently, a rigorous econometric investigation that jointly considers all three dimensions of freedom and their interactions is called for. A natural first step would be to replicate the most recent empirical studies on the relationship between democracy and economic growth (especially Acemoglu et al.), trying to capture the interdependency of democracy and the rule of law (through an interaction term, or at least controlling for initial levels at the time of democratization). From an economic theory perspective, a potential avenue for future research would be to extend the standard growth models of Solow or Romer, introducing mechanisms that capture the level of institutional development in our three dimensions of freedom. In this way, we could gain insights about the specific transmission channels that link different institutional arrangements with economic growth, which could then be translated into practical policy advice regarding the most efficient policy reforms available to less developed countries.

Ignacio Campomanes is resident fellow of the Navarra Center for International Development at the Institute for Culture and Society at the University of Navarra.

Image: Chiefs of indigenous communities of the Amazonas attend a news conference in Lima August 13, 2015. Chiefs of indigenous communities near Peru's biggest oil field, block 192, are pressing for better benefits and environmental monitoring as the government negotiates a new contract with energy companies, according to a media release. REUTERS/Mariana Bazo