Saudi Arabia’s economic shifts under MBS raise stability concerns

Table of contents

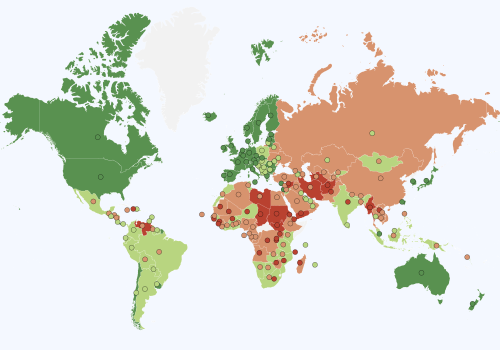

Evolution of freedom

The lack of political freedom in Saudi Arabia has long echoed the lack of social and economic freedom. Saudi Arabia is indeed an absolute monarchy—one endowed with vast oil wealth. Like many other countries in the MENA region, Saudi Arabia is plagued with a concentrated but blurry power structure. Patronage spending and public employment have long been part of a social contract between the ruling elites and the citizenry. But that is changing. Saudi Arabia has embarked on a radical social and economic transformation named Saudi Vision 2030, to move away from its dependence on oil.

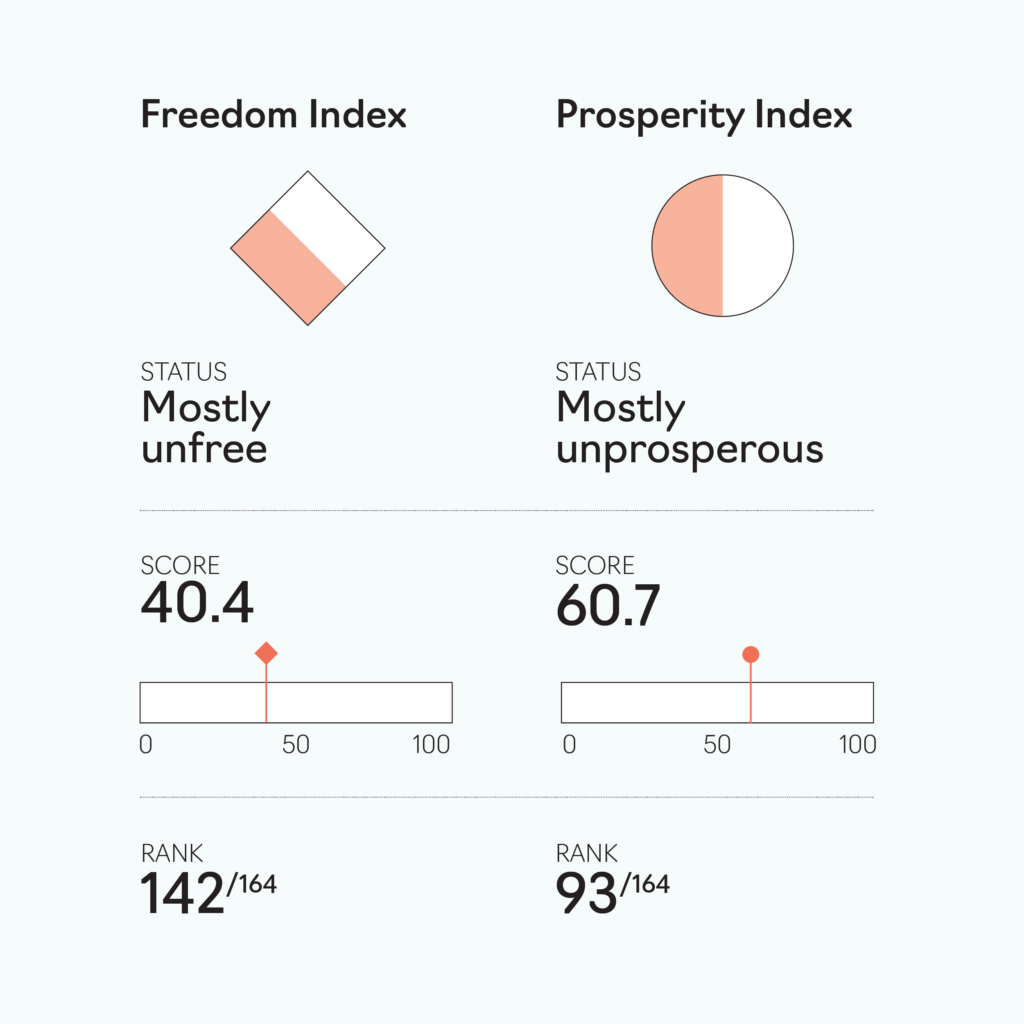

The overall freedom score for Saudi Arabia is indeed low. It hovered around 32 up until 2018. The last four years have seen an improvement of 7.2 points, but it is still almost 7 points below the regional average. The recent improvement in the freedom score is driven by the economic freedom subindex, which has increased by 22.3 points since 2015. Progress in women’s economic freedom and property rights protection lag behind this positive trend, although the Kingdom has indeed taken drastic steps to remove obstacles and empower women socially and economically.

Improvements in economic freedom have been significant but they have not been followed by improvements in political freedom. Saudi Arabia’s score in political freedom is one of the lowest of the world, below 10, and it scores poorly on all indicators of the political freedom subindex. Political rights and civil liberties have regressed. Indeed, the Saudi Vision 2030 agenda has nothing to say on the subject of political transformation. Progress on social and economic reforms should thus not obscure human rights abuses in the Kingdom.

Legal freedom has somewhat improved, with Saudi Arabia’s score increasing by 2.3 points in the last two decades. This has been driven mainly by improvements in the bureaucracy and corruption indicator, in line with the transformation agenda. The Kingdom has scored very poorly on clarity of the law and judicial independence, contrasting with a very high score on informality. The low score for judicial independence echoes the lack of political rights and civil liberties in Saudi Arabia.

From freedom to prosperity

Saudi Arabia’s vast oil wealth has helped finance important social and infrastructure programs. Since 1995, Saudi Arabia has completely closed the prosperity score gap with the MENA regional average, which was initially 4.5 points. This has been driven by the upward trends of the health and education indicators, which have grown at a much faster rate in Saudi Arabia than the regional average. Saudi Arabia’s income score is 17.4 points higher than the regional average, yet the country clearly underperforms on the inequality and minority rights indicators compared to the MENA average, and the trend for both has remained flat.

Saudi Arabia has also invested significantly in education, generating tremendous progress on that indicator, albeit the quality of education is an issue. Despite its high level of education, Saudi Arabia was not faced with the wave of protest movements seen in other MENA countries. Indeed, when the Arab Spring started in neighboring countries in 2010, the Saudi authorities doubled down on patronage to avoid civil unrest. In addition, the social reforms that were part of the transformation agenda may have helped the Saudi regime to get ahead of any large-scale discontent. So far, the lack of political freedom has not resulted in youth unrest. Instead, social reforms—coupled with gigantic investments in entertainments and sports—have helped restore the image of the Kingdom and the Crown Prince, Mohammed bin Salman (MBS), the de facto ruler.

The future ahead

The Kingdom’s transformation agenda is a form of state-led capitalism. The political structure remains unchanged while the economy is reformed. There is no tolerance for any dissent, including on social media where users are watched closely using surveillance technology. The notion that economic transformation can happen independently of political transformation is certainly taking a page out of China’s book; it may prove illusory.

Despite the absence of political freedom, MBS has managed to rally the population behind him. MBS, unlike many leaders in the region, is popular. In fact, he enjoys a level of popularity last experienced by leaders immediately following independence. Such cohesiveness could indeed create momentum for the Kingdom to enact further bold reforms. Yet the escalation of violence between Israel and Palestine risks engulfing the region, and this uncertainty could derail Saudi Arabia’s transformation agenda. While MBS has thus far navigated the new geopolitical environment, it is unclear whether the regional situation—and Saudi Arabia’s place within it—will remain tenable.

What is more, most if not all investments pertaining to the transformation agenda are financed with public money. But the world economy is firmly moving away from fossil fuels, which will leave oil reserves stranded and means that the public money on which the agenda relies will eventually run out. A true test of the sustainability of the economic transformation agenda is whether reforms will attract (domestic and foreign) private investments instead of public investments. All in all, the unbalanced transformation—focused on economic (and social) dimensions alone—may prove illusory as more and more educated youth will demand greater political freedom.

Rabah Arezki is a former vice president at the African Development Bank, a former chief economist of the World Bank’s Middle East and North Africa region, and a former chief of commodities at the the International Monetary Fund’s Research Department. He is now a director of research at the French National Centre for Scientific Research and a senior fellow at the Foundation for Studies and Research on International Development and at Harvard Kennedy School.

EXPLORE THE DATA

Image: Workers prepare the Kiswa, a silk cloth that covers the Kaaba, the sacred building at the centre of the Grand Mosque, ahead of the annual haj pilgrimage, at a factory in the holy city of Mecca, Saudi Arabia July 6, 2022. REUTERS/Mohammed Salem