Dealmaking with China amid global economic uncertainty: Opportunities, risks, and recommendations for Latin America and the Caribbean

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is exerting extraordinary pressure on Latin American and Caribbean economies with reverberations that will be felt for years to come. October estimates point to a 8.1 percent contraction of regional GDP this year, accompanied by a 23 percent reduction in exports. Between January and May, Latin American and Caribbean exports to most destination markets saw sharp decreases, including to the United States (-22.2 percent) and the European Union (EU) (-14.3 percent). However, China—the first major economy to recover from the pandemic—appeared to be an exception (-1.2 percent). As Latin America looks to rebuild from the pandemic, the trajectory of its business relationship with China will be a significant factor in shaping regional outcomes. How can Latin American economies increase their competitive position with China?

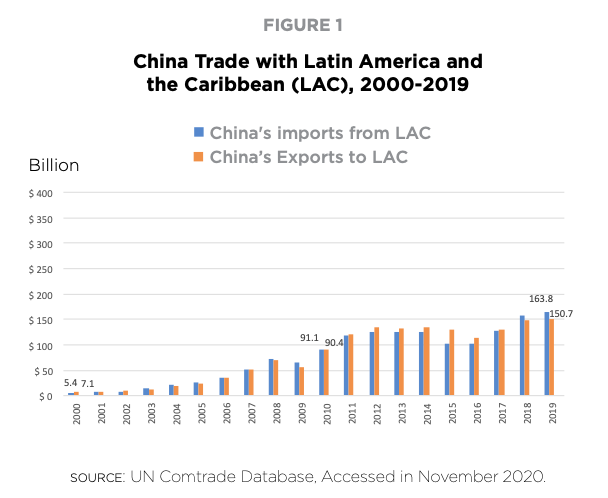

Against the backdrop of an uncertain and uneven global recovery, countries in Latin America are looking to China as an external growth driver. This is not a new phenomenon caused by COVID-19—China had become the region’s second-largest trade partner in 2011. Figures fluctuate year by year, but according to WITS, China has been consistently between the second and third place. China is the second-largest economy in the world with a $14 trillion GDP in 2019. It has a growing middle class of more than four hundred million people who constantly demand more and better imported products and services. Not only is the Chinese economy a top recipient of global foreign direct investment (FDI), but it is also a net exporter of capital with significant investments overseas, including in Latin America.

Although it is right to look at how China is accelerating its commercial relationships with Latin America and the Caribbean, and to understand the drivers for these growing relationships, commercial ties can also increasingly transform into a two-way street. Regional economies, while looking at the United States as an export market, should also more seriously consider how to better tap into China’s growing consumer demand. Certainly, Latin American and Caribbean countries are actively pursuing opportunities in China to grow exports and bring in investment. However, these opportunities are not without challenges or risks. Exacerbating these obstacles is a highly uncertain international environment as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, characterized by business disruptions, including travel restrictions.

Thus, looking ahead, it is essential that each Latin American country design and implement a comprehensive China strategy involving effective coordinated planning, promotion, and risk mitigation. Such a strategy must ensure that countries better understand and respond to China’s growing commercial interests and engagements while safeguarding their national priorities and goals. The following pages provide practical guidance for regional governments and companies interested in engaging China as part of their COVID-19 recovery, outlining the potential challenges ahead and ways to overcome them.

Latin American and Caribbean exports to China

Among Latin America’s main trade partners, China stood out as the top contributor to regional export growth in 2018, and its momentum continued in 2019. Between 2013 and 2016, exports to China fell by 25 percent following the “commodities supercycle.” But from 2017 onwards, exports recovered on account of higher prices of oil and other commodities and trade diversion gains for select regional exporters due to growing US-China tensions. For example, in 2018, Brazil’s soybean exports to China grew from $20.9 billion to $28.8 billion, benefitting from a $6.9 billion reduction in China’s soybean imports from the United States. Notably, much of these gains could unwind depending on the evolution of US-China relations.

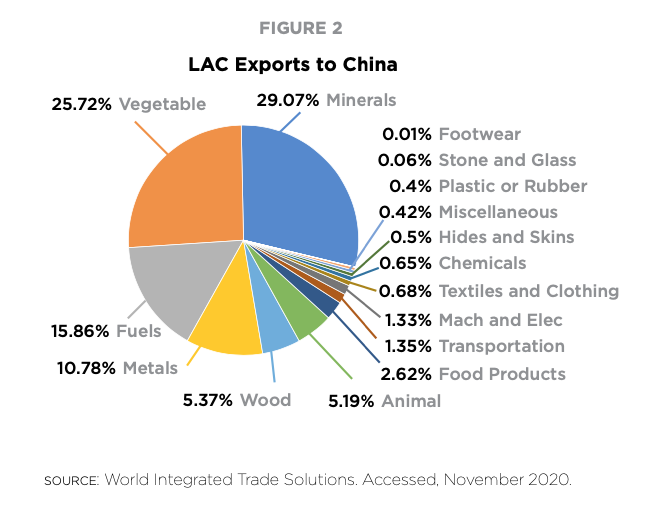

Chinese demand for Latin American products declined at the outset of the pandemic, but quickly recovered. In June, Argentina, Brazil, and Chile each posted a more than 20 percent year-on-year increase in exports to China, bucking global trends of a pandemic-induced trade slowdown. Chinese imports from the region are highly concentrated in commodities and natural resource-based manufactured goods. Five commodities—soybeans, iron ore, copper, refined copper, and oil—account for 70 percent of the region’s exports to China.

As COVID-19 heightens concentration risks in global trade, Latin America must diversify its export basket to China by tapping into new sectors and opportunities, such as the agro-food industry as well as higher-value-added and higher-technology-content products. For instance, World Trade Organization (WTO) figures show that China imported $195 billion in agricultural products in 2018, equivalent to a 10.5 percent share in world imports. The agro-food industry (beyond soybeans) continues to be an important area of opportunity for Latin American exporters. Chinese food demand has and will likely remain relatively inelastic and resilient, even in times of the coronavirus. Oil and industrials, on the other hand, tend to be more prone to cyclical forces.

Challenges and recommendations to increase regional exports to China

Given the size of its middle class and its consumption growth, China is an attractive market for Latin American and Caribbean goods and service exports, albeit a challenging one that draws global competition. This section identifies the main challenges and barriers Latin American stakeholders face in China, followed by corresponding recommendations to overcome them. The analysis derives from the authors’ knowledge and experience gained through years of doing business in China and a detailed analysis of Chinese policies and initiatives.

Each challenge and recommendation is color-coded by its intended audience:

Red for Latin American governments

Blue for companies

Purple for both

Challenge 1. Gain access to the Chinese market.

The Chinese market is still highly regulated in some sectors and, therefore, poses barriers to exporters. Complying with Chinese import regulations and standards can be especially challenging for new exporters or products. Generating and exchanging relevant product information or comparable precedents through institutional channels can bring down some initial barriers.

Government and companies

Recommendation 1: Latin American governments and companies should pursue a two-front effort: 1) Negotiation of trade facilitation measures, dialogues conducted between the government of each Latin American country and the Chinese government, not the private sector and 2) Development of promotion activities. Together, these two types of engagements can help lower transaction costs and time for exporting to China, e.g., tariffs and customs clearance time for specific products. This, in turn, paves the way for furthering Latin America’s export competitiveness and diversification in the Chinese market.

Consistent with global practices, a number of recommended actions are outlined in the first and second versions of “China’s Policy Paper on Latin America and the Caribbean,” an official document, in particular: strengthen exchanges and consultations between customs and quality inspection departments to ensure food safety; promote trade facilitation, and ensure the quality of animal and plant products (including negotiation, standardization, and cooperation on phytosanitary and quarantine protocols); settle trade frictions through consultation; and establish various trade facilitation arrangements and consider concluding free trade agreements.

Challenge 2. Identify potential products for the Chinese market.

While diversification is imperative and attractive, exporting new products to China may prove challenging for some Latin American companies and products due to preexisting local and foreign competition in China, differences in purchasing and consumption habits, lack of networks and access to quality information, as well as language and cultural barriers.

Companies

Recommendation 2: Conduct market research in China—analyze tariff and nontariff measures and figures, and investigate local and foreign competitors, price reports, distribution channels, points of sale, and consumption habits. This comprehensive research will pinpoint demand for both products and services, and match that demand with each country’s export offerings.

The food and beverage sector represents an appealing opportunity. For example, there is a growing Chinese demand for high-quality fresh foods such as avocado, blackberry, raspberry, chia seeds, pecans, grapes, beef and pork, and processed foods such as cereals, fish flour, chocolate, jams, and sauces; and beverages such as fruit juices, wine, beer, tequila, and liqueurs. This demand is due not only to the rising purchasing power and sophistication of Chinese consumers, but the growing importance of food safety in China, and increasingly strict phytosanitary requirements.

Another fast-growing market segment in China belongs to higher value-added and higher technology-content products, including inputs or intermediary goods for these products. Ten high-tech sectors of interest stand out following an analysis of official Chinese documents: next-generation information technology, high-end controlled machine tools and robots, aerospace and aviation “equipment, ocean engineering equipment and high-end vessels, high-end rail transportation equipment, energy-saving cars and new energy cars, electrical equipment, farming machines, new materials, bio-medicine, and high-end medical equipment.” This is particularly relevant for the growing number of Latin American companies venturing into advanced manufacturing.

The region must become more competitive and further insert itself into higher value-add industries globally. In this context, regional companies should avail themselves of China’s innovation push and upgrade industrial capacities and knowledge and develop new specializations. This should not be a China-centric approach: increased sophistication will introduce Latin American firms to new trade and partnership opportunities in markets beyond China. Complementary domestic policy support in Latin America will be critical to these entrepreneurial endeavors, especially in the initial stage.

Challenge 3. Ensure brand protection.

Without the proper paperwork, Latin American businesses and entrepreneurs may face the risk of losing brand protection, especially when participating in business delegations, trade expos, or when sharing information with their Chinese counterparts.

Companies

Recommendation 3: Start the trademark registration process in China before beginning to explore that market, otherwise another person may register the brand. The application must be submitted to the China Trademark Office (CTMO); it is possible to hire local agents offering remote services. Local agents will require a proxy letter and a copy of the respective trade registration, e.g., in Mexico’s case, the Federal Taxpayer Identification Number. Then, select the relevant class and specify the products or services, the brand name, logo, or product name in question. A final resolution from the Chinese authorities will come in approximately one year unless information is missing. Another option to protect a trademark in China is by designating China under the Madrid System for the International Registration of Marks, which is governed by the Madrid Agreement and the Protocol relating to that agreement.

Challenge 4. Find trustworthy Chinese importers.

Driven by ever-evolving domestic consumption trends, Chinese wholesale buyers or importers are usually interested in exploring new business opportunities, even in sectors they consider prospective and unfamiliar. The challenge is finding the right Chinese partner with the necessary skills, resources, and willingness to build a productive and transparent long-term relationship.

Companies

Recommendation 4: Latin American exporters should procure and analyze databases listing goods imported by Chinese customs to identify potential buyers for products. Such databases should include product description, value, amount, unit, country of origin, the customs office where the goods were presented, and the importer’s name and contact details. Upon identifying a potential customer, exporters should perform due diligence and essential background checks on the company, negotiate an international purchase and sales agreement, and use letters of credit as a safe form of payment.

Challenge 5: Successfully import products into China.

Latin American companies trying to sell their products in China usually fail to carefully prepare their market entry strategy. Such strategy should consider packaging, labeling, standards, certifications, and logistics. Some of these issues can be particularly troublesome for food and beverage products.

Companies

Recommendation 5: Determine which tariff and nontariff measures will apply to the product upon entering the Chinese market, and whether the import is possible. Acquire tariff-related information based on the respective tariff item number and country of origin. Nontariff requirements may include necessary certifications and modes of transport allowed for imports. For example, fresh food consignments must be accompanied by a phytosanitary certificate documenting compliance with the relevant protocol mutually agreed by the corresponding governments. If the relevant product can be imported, prior market research is advisable to help devise an appropriate entry strategy.

Recommendation 6: Find Chinese companies that offer integrated logistic services for both traditional and cross-border e-commerce imports so that products can be placed physically in China, maximizing margins and control. The services offered by this type of local partner may include Chinese label design and application, advice on nontariff measures, import commercial inspection, product storage, and distribution, among others.

Lists of reliable companies providing this kind of service may be requested from China Council for the Promotion of International Trade (CCPIT), the China Chamber of International Commerce (CCOIC), and other government agencies or chambers of trade and commerce. After selecting a provider, sign a services agreement specifying the responsibilities of each party and containing provisions regarding confidentiality agreements, intellectual property protection, dispute resolution, and terms of the agreement.

Challenge 6. Develop commercialization strategies for products in China.

This challenge involves forging and signing cooperation agreements between regional companies and points of sale or prospective customers in China.

Photo: A staff member stocks imported seafood products at a supermarket in Beijing, China Chinese demand for food and beverage products will continue to be a key driver for Latin American exports. Picture taken: November 2020. (REUTERS/Thomas Peter)

Government and companies

Recommendation 7: Take advantage of foreign and local hypermarkets—marketplaces with an imported products section—supermarkets; convenience stores that specialize in imported goods; e-commerce platforms such as Taobao.com, Tmall.com, and JD.com; as well as social media platforms, including WeChat, to sell consumer products. Request a virtual meeting with a company representative or contact an authorized distributor to find out more about specific requirements for product placement. Embassies, consulates, and promotion offices for Latin American countries in China, CCPIT, and CCOIC may provide valuable contact information. As COVID-19 complicates international travel, organizations that possess or leverage in-person representation and networks in China will have an advantage.

Recommendation 8: Strengthen e-commerce cooperation. Companies such as Alibaba Group, JD.com, and other wholesale and retail stores operate e-commerce platforms through which they sell clothes, household essentials, home appliances, fresh and processed foods, among other products. Alibaba Group’s Tmall.com has virtual platforms that offer products from specific foreign countries. Latin American and Caribbean governments could sign agreements with these companies to launch virtual, country-specific platforms, enabling promotion of products. In 2017, the Mexican government and Alibaba Group signed a memorandum of understanding to facilitate companies’ access to the platform, training entrepreneurs, and sharing insights on logistics operations and payment systems. That same year, the government of Argentina signed an agreement with Alibaba Group to promote wines and fresh food through its various e-commerce platforms in China.

Recommendation 9: Secure backing from Latin American governments or chambers of commerce to approach and sign cooperation agreements with major Chinese importers, distributors, and buyers. For example, it would be beneficial to advance cooperation agreements in the agro-food industry with China National Cereals, Oils, and Foodstuffs Corporation (COFCO Corporation), the largest food company in China, and Joyvio Group, a well-recognized brand for high-quality food and beverage products. These companies not only buy large volumes of products, but also have deep knowledge of the market, expertise, distribution channels, and contacts.

Recommendation 10: Identify multinational companies present both in China and Latin American countries, such as car assembly plants and manufacturers of electronic devices, appliances, and medical equipment. These companies are more inclined to have globally integrated supply chains and procurement processes. Encourage these global companies to source component parts and raw materials from Latin American suppliers for their plants in China, or vice versa. Examples of possible companies are Mabe, Ford, LG, and Volkswagen.

Challenge 7. Conduct effective promotion activities for Latin American products in China.

Localized marketing and awareness campaigns can compensate the lack of in-depth knowledge of Latin American countries and products in China. Latin American exporters must also increase their representation at Chinese trade fairs and expos, as well as improve their understanding of the Chinese language, business practices, and consumption preferences.

Governments and companies

Recommendation 11: Companies should support promotional activities organized by Latin American embassies, consulates, promotional agencies, chambers of commerce, and companies. Events similar to the China International Import Expo (CIIE) offer a unique opportunity for countries to showcase all they produce to large distributors and buyers in China. Despite the pandemic, many of these events continue to take place virtually. Specifically, for the agro-foods industry, share relevant information on Chinese social media and organize more face-to-face and virtual gastronomic festivals to help better position high-quality food and beverage products in hypermarkets and e-commerce platforms. Many Chinese procurement officers have limited knowledge of what the Latin American and Caribbean region offers, and there is a general misconception that products from this region may be of lower quality. One example of a supermarket chain offering imported products that is involved in country-themed gastronomic festivals is City Shop, based in Shanghai and Beijing. Outside of the major cities known to most foreigners, the rise of “second-tier” cities in China may also offer interesting opportunities going forward. There are more than twenty cities in China with more than four million inhabitants, i.e., a sizable consumer base.

Recommendation 12: Governments can help foster exchanges between the private sector in Latin America and China that will lead to mutually beneficial cooperation. Within the private sector, promote the China-Latin America and the Caribbean Business Summit, held annually in China or Latin American and Caribbean countries on a rotating basis. Enhance cooperation between the region’s chambers of commerce, CCPIT, and CCOIC to take advantage of their platforms and promote foreign products. Offer business opportunities on social media such as WeChat and arrange face-to-face and virtual meetings with importers and distributors in various provinces. CCPIT also has offices in Brazil, Costa Rica, Chile, Mexico, and Panama.

Challenge 8: Boost exports from Latin American small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to China.

Often, SMEs lack access to professional advice, reliable information, or other support services that allow them to make well-informed decisions in the Chinese market. While the preceding recommendations apply to SMEs as well, additional hand-holding might be needed to help them execute and follow through.

Governments and companies

Recommendation 13: Promote the transfer of knowledge and experiences between companies already selling products or services in China and SMEs interested in doing business in that market. Governments and chambers of commerce should organize seminars and face-to-face and virtual meetings to share success and failure stories, or prepare case studies to share them in regional and international business platforms such as the Inter-American Development Bank’s (IDB) ConnectAmericas.

Recommendation 14: Disseminate more information about the characteristics, environment, opportunities, and challenges posed by the Chinese market, and offer specialized services to raise awareness about China among Latin American entrepreneurs. A European Union (EU) initiative that the region could adopt is the EU SME Centre, which provides support services to European SMEs preparing to do business in China. Its team of experts provides advice in four areas: business development, law, standards and compliance, and human resources.

ProChile is a success story that could serve as a model for an LAC SME Centre in China. This division of Chile’s Ministry for Foreign Affairs designed a program called PYMEXPORTA to provide advice, training, information, and support research on international markets, and other instruments to boost SME exports. In China, ProChile has offices in Beijing, Guangzhou, and Shanghai, all of them conducting promotional activities such as commercial missions, organizing business roundtables, and supporting foreign trade projects. Chile’s wine exports to China stand out as an example. In 2016, China became Chile’s largest wine importer, and despite recent drops in consumption associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, China is still a leading market for Chilean wine. Besides, small Chilean wine producers have successfully entered the Chinese market by studying Chinese demand and participating in trade fairs.

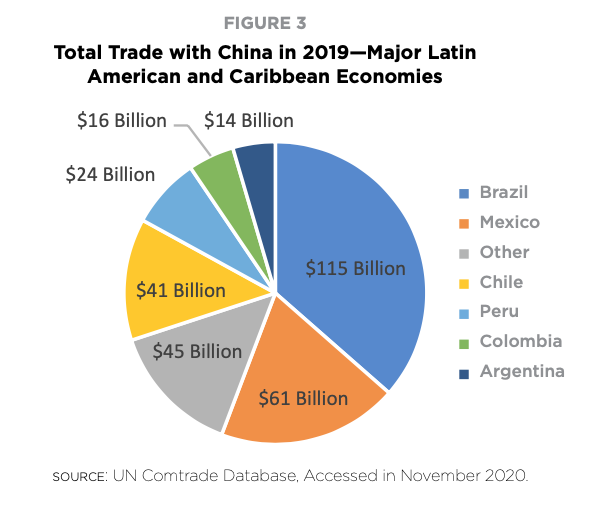

Case study: Mexico

International Monetary Fund projections from October estimate a -9.0 percent GDP contraction for Mexico in 2020 as a result of COVID-19. With all hands on deck, Mexico seeks to accelerate recovery through export growth, not only with key partners in North America but also in Asia. Mexico is China’s second-largest trading partner in Latin America. In 2019, China-Mexico trade amounted to $97.40 billion. Mexican exports to China amounted to $14.35 billion, i.e., a $83 billion trade deficit. Major exports were copper ores and concentrates, auto parts and accessories, nine-passenger vehicles, lead ores and concentrates, cathodes and sections of cathodes, silver ores and concentrates, automatic gearboxes, and automatic data processing machines.

These figures show Mexico’s potential to further grow and diversify its exports (including value-added contributions) to China. The Mexican economy is highly sophisticated and is competitive in providing raw materials and components for various sectors, including industrial and agricultural. Mexico is the eleventh-largest producer and the tenth-largest exporter of food products worldwide. The introduction of Mexican avocado in China is a success story, with avocado exports growing from 153.6 tons worth $354,600 in 2012 to 14,962.7 tons worth $48.2 million in 2018.

A salient success story of Mexican exports to China is that of a well-known Mexican beer. However, to achieve its current popularity in China, this Mexican brand has had to overcome great challenges, particularly in terms of trademark protection (Challenge 3 above).

The first Chinese importer of the beer registered the trademark under its name without the Mexican company’s consent. The International Law division of the Mexican company demanded that the importer hand over the trademark within two weeks. Failure to comply would rescind the respective contract. This action successfully curtailed the importer, who immediately started preparing all of the necessary paperwork to relinquish the corresponding rights.

Later, the Mexican company had to take legal action against two different counterfeits. The first counterfeit was a beer bearing a label with slight changes from the original and a bigger bottle sold for less than the original beer, causing confusion among consumers. The second counterfeit had a bottle and label that were almost identical to the original, but it was sold at a noticeably lower price, severely affecting the Mexican beer’s sales. Mexican authorities had to step in to help the company resolve the problem.

Despite these challenges, by working closely with the distribution network and legal professionals, the company managed to improve sales and enhance this Mexican beer’s image in China. In 1992, China imported only 9,000 cases of this beer. Imports went up quickly, to 228,000 cases in 1998, half a million cases in 1999, and more than 1.3 million cases in 2004. By 2018, China had become the number one export market for the brand in the world.

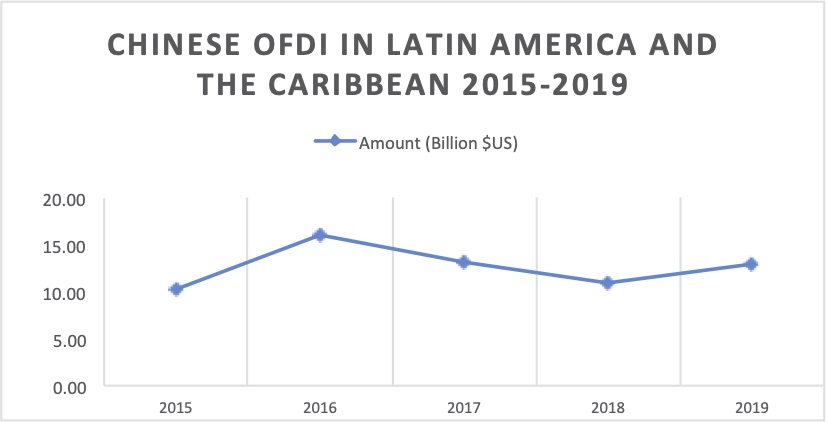

Chinese investment in Latin America and the Caribbean

China has ranked among the world’s top three contributors of outbound foreign direct investment (FDI) since 2013. While Chinese investment in Latin America still trails behind that of the United States and Europe, it has consistently accounted for more than 6.5 percent of annual regional FDI inflows since 2016. In particular, China has become a relevant player in the mergers and acquisitions (M&A) space, overtaking the United States and Europe as Latin America’s top M&A investor in 2016 and 2017. Chinese FDI in Latin America has been concentrated mainly in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Mexico, and Peru.

Initially, Chinese investment in Latin America went almost exclusively to commodities and infrastructure to facilitate resource extraction. In recent years, Chinese companies have shown a growing interest in a range of new sectors, including electricity, information and communications technology, finance, and transport. Between 2013 and 2016, these services sectors accounted for 50 percent of Chinese FDI in Latin America. Such an evolution came about due to China’s supportive domestic policies prioritizing these sectors, its need to internationalize certain domestic industries and adapt to its “new normal” economic reality, among other factors.

A careful analysis of foreign policy documents and initiatives proposed by the Chinese government for Latin America and the Caribbean confirms this trend. The Chinese government encourages and supports qualified Chinese companies to invest in projects and sectors in the region, including infrastructure construction such as transport, information and communications, water conservancy and hydropower, and in agriculture, forestry, fishing, energy, and mineral resources. Lately, there has been an emphasis on industrial investment and production capacity cooperation in automobiles, new energy equipment, motorcycles, and chemical industry. Connectivity has been an important policy focus, ranging from logistic connectivity (mainly regarding railways), electricity (transfer of highly efficient energy and smart networks) to computing (new generation Internet technologies, mobile telecommunication, “big data,” and cloud computing). Connectivity is also a prominent feature of the China-led Belt and Road initiative.

Current regional priorities around Chinese FDI are to sustain Chinese investment inflow, further diversify its destination countries and sectors, and ensure quality and fairness. These ambitious goals are challenging in light of an ongoing downward trajectory in global and Chinese FDI outflows, compounded by the economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, Latin America has bucked global trends on a number of occasions, being the only region to see year-on-year growth in Chinese FDI in 2017 and 2019.

Challenges and recommendations to secure quality, productive, and sustainable FDI influx from China to Latin America and the Caribbean

As China continues its role as a relevant investor in Latin America, it is necessary to develop a comprehensive strategy to better understand the needs of the Chinese government, state-owned companies, and private companies. Matching them to the interests of each country—which may vary widely—will help minimize risks and maximize profits.

Below is a list of challenges that Latin American countries often face when trying to attract high-quality, productive investments from China that contribute to their socioeconomic development, followed by practical recommendations to overcome them.

Each challenge and recommendation is color-coded by its intended audience:

Red for Latin American governments

Blue for companies

Purple for both

Challenge 1. Find prospective investors.

Many Chinese companies are increasingly looking to invest abroad, with varying degrees of interest and success. The real challenge is finding experienced investors with the necessary financial capacity, international management talent, and competitive drive to enter and navigate Latin America, an unfamiliar frontier market for most Chinese firms.

Government and companies

Recommendation 1: Identify leading Chinese companies in each productive sector listed above—prospective investors—based on research conducted by public and private sector organizations working to attract foreign investment to Latin America. Skim through lists and company directories prepared by government agencies, chambers of commerce, and research centers in China.

Note that Chinese investors are increasingly interested in exploring joint ventures, public-private partnerships, or joint franchises with local organizations. As with other international investors, this partnership approach derives from the need for local knowledge and networks critical to project origination and execution, as well as specific FDI or foreign property ownership regulations in host countries. China also promotes bilateral financial partnerships through government support. This may include specialized funds such as the China-LAC Cooperation Fund or the China-Latin American Production Capacity Cooperation Investment Fund, preferential loans, and specific infrastructure loans.

Recommendation 2: Specifically for the manufacturing sector, examine entry of goods databases through US and other national customs to identify qualified Chinese manufactures and investors. Amid the ongoing US-China trade tensions and a COVID-19-induced global shortage of critical goods, consumers and governments worldwide are seeking to bring supply chains closer to home. This could create reshoring/nearshoring opportunities, for example, for Mexican and Central American public and private institutions. Trade-oriented companies and investors from China, the United States, and the region itself can be interested in these nearshoring investments. Truly competitive nearshoring proposals must go much beyond simple geographic relocations. Rather, they should help reduce costs of production, logistics, or import tariffs and improve access to new or existing markets.

Challenge 2. Efficiently disseminate possible Latin American investment destinations and projects in China.

Foreign institutions can struggle to find the right counterparts and communication channels to reach a larger audience of prospective Chinese investors. This challenge hurts Latin America disproportionately because Chinese investors tend to gravitate toward opportunities in more familiar and established markets such as the United States and Europe.

Government and companies

Recommendation 3: Encourage government agencies, chambers of commerce, and research centers in Latin America to sign collaboration agreements with their Chinese counterparts. The aim here is to take advantage of institutional communication channels to share investment destinations, plans, and projects with prospective investors.

Some examples of institutional communication channels: the China Investment Promotion Agency (CIPA) compiles and publishes investment guides for different countries; CCPIT and CCOIC could also help. These organizations have business platforms, magazines in Mandarin and English, and a strong presence in social media such as WeChat. They may also help to disseminate Latin American investment opportunities using their information newsletters, investment reports, investment seminars, courses, videoconferences, trade missions, and business planners, among other resources.

Recommendation 4: Support Latin American governments and private sectors to solidify alliances with multinational financial institutions and consultancy firms. On one hand, these organizations actively identify and help originate investment deals in Latin America. On the other hand, they are also always seeking to offer a wider range of services and investment projects to their clients in China. Their global footprints and networks make them a natural bridge between Chinese investors and Latin American investment opportunities that may not be connected otherwise. An interesting aspect of this is the increasing internationalization of renminbi, well-documented in a previous Atlantic Council study.

Recommendation 5: Attend, physically or virtually, the China International Fair for Investment & Trade (CIFIT) or similar events, organize investment seminars both in tier one and tier two cities (the latter will involve less competition to attract investment), run private events with top executives of Chinese companies, and use business and social media platforms such as WeChat, Weibo, and Youku to release information, investment projects, and promotional videos, or live-stream seminars.

Challenge 3. Prepare investment projects that foreign investors find both appealing and feasible.

Given the fierce competition for Chinese investment, it will be challenging to grab investors’ attention and keep them interested using the limited available information. This challenge is exacerbated by the ongoing pandemic which has disrupted business travel and face-to-face meetings.

Photo: Aerial shot of Bogotá, Colombia. Colombia has increased its commercial ties with China, becoming China’s fifth largest trading partner in Latin America, and a growing destination of Chinese investment. Picture taken: September 2019. (Unsplash/Random Institute)

Government and companies

Recommendation 6: Present business plans in Mandarin clearly demonstrating the project’s economic and financial viability. The project should also clearly state the competitive and comparative advantages of the investment destination, such as political stability, privileged geographic position, existing trade agreements, competitive production and logistics costs, human capital, domestic market potential, and intellectual property enforcement. Provide additional follow-up support to further the interest of Chinese investors and simplify their decision-making process.

It is essential to ensure that there are mutual benefits. Countries should prepare and present portfolios with specific projects, establish stable and fair regulatory frameworks, and maintain appropriate tracking/monitoring mechanisms. This contributes to a better business environment and increases the chances of attracting FDI—not only from China, but from other countries as well. It also helps ensure transparency and standards in project design and implementation down the road.

Challenge 4. Deal with state-owned enterprises (SOEs).

SOEs are behind many major Chinese trade and investment projects abroad, including in Latin America. As a result, a growing number of Latin American countries are engaging them for partnerships and investments. Countries must understand this is a relationship and trust-building process that usually takes considerable time and resources given the size, appetite, and pace of these SOEs.

Government and companies

Recommendation 7: Acquire institutional support to approach these companies. For example, sharing investment projects and finding contacts through Chinese embassies, consulates, CIPA, CCPIT, CCOIC, and Chinese chambers of commerce. Public and private partners should also seek assistance from Latin American countries with embassies, consulates, and promotion agencies in China.

One weakness of some state-owned companies is that their management lacks up-to-date information or experience in international expansion processes, which increases their desire for quality information and support. Other SOEs have overseas representations and offices in Latin America and are, therefore, better prepared to tackle this information barrier. However, key decision-making tends to happen at the SOE’s headquarters in China, sometimes without fully incorporating inputs from regional offices. This could create an additional layer of communication and procedural complexity for Latin American governments or companies unfamiliar with the process.

Recommendation 8: Protect the interests of all parties involved in the investment process by signing a collaboration agreement that establishes the responsibilities, designates means of communication, institutes confidentiality and intellectual property protections, and designates dispute resolution mechanisms. Government backing is desired due to the nature and size of many investments involving SOEs, e.g., large-scale infrastucture projects.

Challenge 5: Enhance the transparency of China’s investment projects in Latin America to attract productive investment that boosts growth and socioeconomic development.

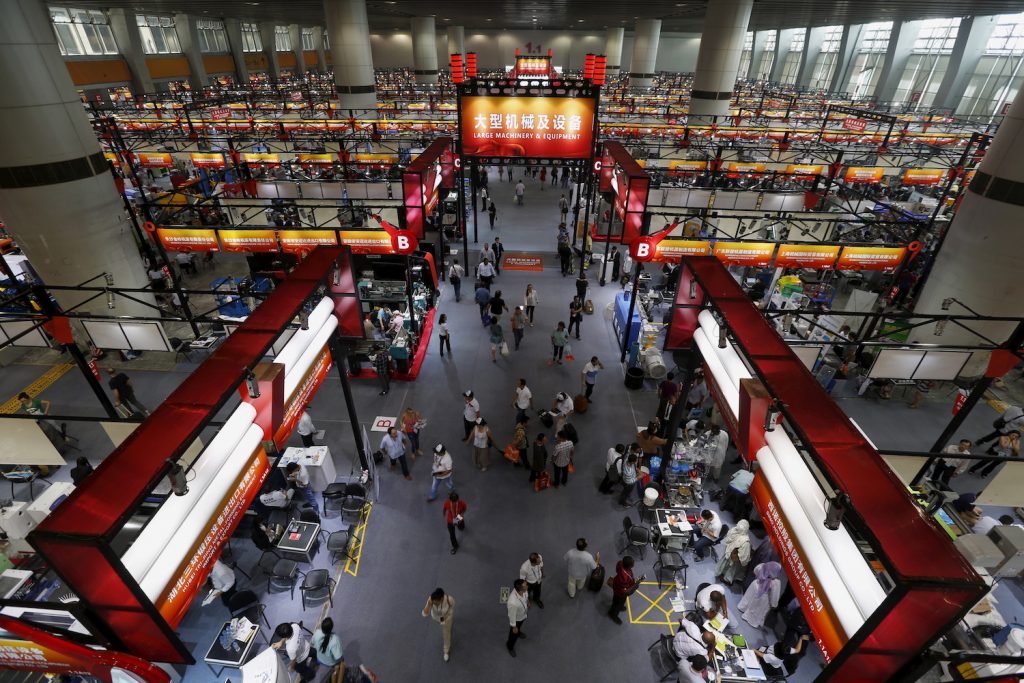

Photo: Trade expos or investment fairs, including the Canton Fair (pictured), are a key resource for Latin American companies to raise awareness of their product and project offering in China. Picture taken: October 2015 (REUTERS/Bobby Yip)

Some previous Chinese projects in the region have had adverse social and environmental effects. Although many Chinese firms have demonstrated a steep learning curve in addressing these concerns, well-thought-out policies and efforts from Latin American governments can help to further accelerate this process.

Government

Recommendation 9: Latin American governments should take steps to ensure that investment projects and bidding processes strictly abide by all laws, rules, and regulations in the destination country. Procurement, labor, environmental, and corporate social responsibility have been among the top areas of concerns. Active monitoring by governments and frequent consultations with local communities and civil society are essential in mitigating these risks. Additionally, transparency systems should be strengthened and rights to access information should be protected. This will help create a healthy business environment and reduce adverse social or environmental impact.

The comparative experience of working with and learning from non-Chinese investors is essential and complementary. The United States, for instance, has been a champion of promoting higher standards and greater transparency in investment projects in Latin America. Amid ongoing US-China tensions, most governments in the region are taking a measured neutral position and have declined to publicly choose sides. By working constructively with both countries in different areas, they aim to avoid the geopolitical spillovers while creating a welcoming environment and level playing field for all foreign investors. Indeed, high-quality FDIs—from China, the United States, and beyond—will be indispensable to rebuilding Latin American and Caribbean economies after the pandemic.

Case study: Mexico

China’s investment in Mexico is still low, especially compared to other Latin American countries, including Argentina, Brazil, and Peru. According to statistics from Mexico’s Ministry of Economy, as of year-end 2019, total FDI from China and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region was $2.2 billion, with one thousand three hundred and seven Chinese and Hong Kong companies having registered in Mexico.

Mexico and China both have an industrial manufacturing base and a high proportion of their production is devoted to exports. While competing in many cases, they may also complement each other by integrating value chains and conducting joint manufacturing operations. Additionally, they can undertake more ambitious projects such as creating industrial agglomeration areas within Mexico that contain companies of both countries. The end result could enhance both Chinese and Mexican products’ production processes and their competitiveness in the international market. The following sectors are most likely to benefit from such industrial complementarity: automotive, electronics, domestic appliances, and—in the future—aerospace and biotechnology sectors.

Many Asian investment projects in Mexico—involving South Korean and Japanese carmakers—have demonstrated this proposal’s viability. A recent example was the joint venture signed by JAC Motors of China and Mexican car maker Giant Motors Latin America to expand an assembly plant in Ciudad Sahagún in the state of Hidalgo. Mexico is becoming the manufacturing center of JAC Motors for Mexico’s domestic market and an export gateway to other Latin American countries. This $230-million alliance (equivalent to more than 4.4 billion pesos) was announced in 2017, creating one thousand direct jobs and roughly four thousand five hundred indirect jobs in its first stage. It also involved coordinating efforts between the private and academic sectors to develop capabilities and patents.

To make this deal happen, Mexico and China have worked together to overcome several investment barriers. For a few years, JAC Motors executives have been in constant communication with the various offices representing the Mexican government in China to obtain information on market potential and investment advice. A growing number of Chinese companies are emulating this practice. There is tremendous value in finding an experienced local partner with a deep understanding and knowledge of the destination market, the Mexican automobile market in this case. By combining complementary resources and skills, joint projects increase the chance of success for all parties involved.

Conclusions

China represents a unique commercial opportunity for Latin America but with associated risks and challenges. Designed for Latin American public and private sector leaders interested in negotiating with China, this report identified eight challenges and fourteen recommendations to increase Latin American exports to China, and five challenges and nine recommendations to secure quality, productive, and sustainable Chinese investments, as summarized below.

Challenges and recommendations to increase exports from Latin America and the Caribbean to China

| For… | Challenge | Recommendation |

| Government & companies | 1. Gain access to the Chinese market | 1. Negotiation of trade facilitation measures and development of promotional activities |

| Companies | 2. Identify potential products | 2. Conduct in-depth market research |

| Companies | 3. Ensure brand protection | 3. Start the trademark registration process in China before beginning to explore the market |

| Companies | 4. Find trustworthy importers | 4. Identify and vet prospective buyers in China from reliable sources |

| Companies | 5. Successfully import products into China | 5. Examine tariff and nontariff requirements; 6. Develop or hire integrated logistics services |

| Government & companies | 6. Develop commercialization strategies for products in China | 7. Identify points of sale and prospective consumers; 8. Strengthen e-commerce cooperation; 9. Enter cooperation agreements with Chinese importers, distributors, and buyers; 10. Work with multinational companies with integrated supply chains across China and Latin America |

| Government & companies | 7. Conduct effective promotion activities for Latin American products in China | 11. Attend and support trade promotion activities in China; 12. Enhance cooperation between not only companies but also business support organizations in Latin America and China |

| Government & companies | 8. Boost exports from Latin American SMEs to China | 13. Promote transfer of knowledge and experiences between companies; 14. Integrate SMEs into a broader export promotion strategy |

Challenges and recommendations to secure quality, productive,and sustainable FDI influx from China to Latin America and the Caribbean

| For… | Challenge | Recommendation |

| Government & companies | 1. Find prospective investors | 1. Identify leading Chinese companies in each productive sector; 2. Examine information on the entry of goods through customs to identify prospective Chinese investors |

| Government & companies | 2. Efficiently disseminate possible investment destinations and projects in China | 3. Encourage Latin American institutions to sign collaboration agreements with their Chinese counterparts; 4. Help materialize alliances with multinational financial institutions and consultancy firms; 5. Attend investment fairs, organize seminars, run private events, and use online platforms |

| Government & companies | 3. Prepare appealing and feasible investment projects | 6. Present business plans in Mandarin that include relevant information of interest to Chinese investors and simplifies their decision-making process |

| Government & companies | 4. Deal with state-owned companies | 7. Acquire institutional support to approach these companies; 8. Protect the interests of all parties involved in the investment process by signing a comprehensive collaboration agreement |

| Government | 5. Enhance transparency to attract productive investment that may boost growth and socioeconomic development | 9. Ensure that investment projects strictly abide by laws, rules, and regulations applicable in the destination country. Transparency systems should be strengthened and rights to access information should be protected. |

Latin America must sharpen its competitive and comparative advantages by synergizing supportive public policies and the private sector’s dynamic entrepreneurial drive. This will help the region better position itself as a strategic partner for China, as well as for other regions or countries in the world. The timeliness and importance of taking these actions cannot be overstated. The health crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic will produce a deep lethargic spell in economies worldwide that will be felt for years to come. The region cannot afford to have another “lost decade.” To ensure a robust post-pandemic recovery, it is fundamental to strengthen, diversify, and improve economic linkages with commercial partners around the world.

Surviving and competing in a post-COVID-19 world will require Latin American leaders to take bold and wide-ranging decisions; seek innovative, intuitive, and far-reaching solutions; and quickly adapt and evolve. In China-Latin America relations, governments and companies in the region must explore possibilities to apply, virtually and innovatively, the specific strategies and recommendations outlined above.

Among many other new opportunities that may arise in a post-COVID-19 future is digital trade. More international commercial transactions will happen electronically through new and existing platforms. In the next few years, e-commerce growth will likely exceed that of traditional brick-and-mortar retail around the world, both in volume and value terms. China is a global leader in e-commerce; Latin America’s trade flows with China may benefit from this.

Latin American SMEs may have a special opportunity here. Traditionally, SMEs cannot afford the costs of appointing a trade broker or setting up a representation office in China or other export destinations. However, in a more digitalized future, SMEs may enjoy unprecedented global reach through online platforms, from the comfort of their office, factory, or company. Latin American governments must continue the crucial and urgent mission of supporting SMEs and facilitating trade through digitalization.

Finally, a deeper, more nuanced, and comprehensive understanding of China (its interests, opportunities, challenges, and risks) is more important than ever. Businesspeople and entrepreneurs can benefit from attending relevant exhibitions, seminars, and training courses. Latin American and Chinese government agencies and chambers of commerce offer these programs and incentives. Countries should also strengthen educational, cultural, and other non-commercial exchanges with China. If done properly, trade, investment, and practical cooperation with China will make a positive contribution to economic development and recovery in Latin America and the Caribbean.

NOTE:

This report does not necessarily reflect the analysis or position of the Atlantic Council, but that of the authors. For any comments or queries, please contact the authors.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank The Atlantic Council for the opportunity to share information and concrete ideas concerning foreign trade and investment for Latin America and the Caribbean. In times of uncertainty, we hope this information provides a sound basis to design public policies and business strategies that may benefit countries in the region, increasing exports and attracting more investment. At the Atlantic Council, we also would like to thank Jason Marczak and Pepe Zhang for their guidance and excellent contributions that have greatly improved this report; Pablo Reynoso, Beatriz Godoy, and Daniel Payares for their excellent research support; and Susan Cavan for editorial assistance. Finally, a special thank you to the Mexican Business Council for Foreign Trade, Investment and Technology (COMCE) and its chairman, Mr. Valentín Diez Morodo, for their relentless work promoting exports and attracting investment.

Sergio Ley López

Salvador Suárez Zaizar

About the authors

Sergio Ley López

SergioLey López joined the Mexican Business Council for Foreign Trade, Investment and Technology (COMCE) in March 2009 as chairman of the Asia and Oceania Business Section. In August 2014, he took office as vice-chairman. A career diplomat since 1984, he was the cultural attaché at the Embassy of Mexico in the People’s Republic of China from September 1984 to July 1990. From July 1990 to August 1993, he was the deputy chief of mission at the Embassy of Mexico in Singapore. He was consul general of Mexico in Shanghai between August 1993 and December 1994 and director general of the Pacific and Asia for the Mexican Ministry of Foreign Affairs between January 1994 and March 31, 1997. From 1997 to 2001, he served as Mexico’s ambassador to the Republic of Indonesia. From November 2001 to January 2007, he served as the ambassador of Mexico to the People’s Republic of China.

After completing his diplomatic duties, he started working as an external consultant, and in 2007 joined the Mexican Council on Foreign Relations (COMEXI). He was a fellow at the School of International Relations and Pacific Studies and the Institute of the Americas in the University of California, San Diego. Since October 2008, he has been a non-voting board member of the Institute of the Americas, UCSD. In January 2008, he was appointed president of the Asia-Pacific Institute at Tecnológico de Monterrey (ITESM), based in the Mexico City and Guadalajara campuses. Between 1973 and 1983, he served as general director, manager, and member of the board of directors of several companies. From 1969 to 1972, he was general director of public works for the local government of Culiacán, Sinaloa.

Ley has been a keynote speaker at various universities, including ITESM, IPADE Mexico City, and numerous regional chapters of COMCE. He graduated from the National School of Architecture at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. He did his postgraduate studies in art history at the University of Paris, France, and received a master’s in restoration of historical buildings from the Institute of Archaeology at the University of London, England.

Salvador Suárez Zaizar

Salvador Suárez Zaizar is currently a partner at the Mexican consultancy firm GPerspective Trading, Logistics & Consulting, S.A. de C.V., which specializes in the attraction of investment and in food exports to China. Between October 2013 and October 2015, he was head of bilateral affairs at the Embassy of Mexico in the People’s Republic of China. Previously, from April 2009 to October 2013, he served as director of the Asia and Oceania Business Section of the Mexican Business Council for Foreign Trade, Investment, and Technology (COMCE). Between 2006 and 2008, he attended the Mexico-China Business Development Program in Hangzhou and Shanghai providing market research services to Mexican companies in the logistics of automotive and agro-foods sectors.

Suárez has advised a wide range of public and private sector clients on doing business in China, written China-related columns for media outlets, and delivered lectures and conference talks on China at various organizations including Tecnológico de Monterrey (ITESM), the Confucius Institute of the Autonomous University of Yucatán, the University of Colima, and others. He holds a bachelor’s degree in International Trade from ITESM, Monterrey campus.

The Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center broadens understanding of regional transformations and delivers constructive, results-oriented solutions to inform how the public and private sectors can advance hemispheric prosperity.