Countering China’s challenge to the free world: A report for the Free World Commission

This report draws on a recent Atlantic Council Strategy Paper, Global Strategy 2021: An Allied Strategy for China, prepared by Matthew Kroenig and Jeffrey Cimmino, which featured contributions from a group of experts from leading democracies. The report focuses on the challenges that China poses to global governance and democracy, ands highlight recent activities taken by democracies to address these challenges. It also reiterates those elements of the Strategy Paper that relate to strengthening cooperation among leading democracies, defending the free world against Chinese interference, and engaging Beijing on international norms.

The views expressed in this publication represent those solely of the authors and are not intended to imply any endorsement of the content by members of the Free World Commission.

Executive summary

Over the past seventy-five years, leading democracies have constructed a rules-based international system that has generated unprecedented levels of peace, prosperity, and freedom. The system, however, is coming under increasing strain, especially from the reemergence of great power competition with China. The increasing assertiveness of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) poses a significant challenge to the interests and values of likeminded allies and partners and the rules-based system.

To address this challenge, leading democracies, including the United States and its allies and partners across Europe and the Asia-Pacific, will need to work together to implement a coordinated strategy. The approach set forth in this paper proposes a strategy based on three elements: strengthening likeminded allies and partners and the rules-based system for a new era of great-power competition; defending against Chinese behavior that threatens to undermine core principles of the rules-based system, and engaging China from a position of strength to cooperate on shared interests and, ultimately, incorporate China into a revitalized and adapted rules-based system.

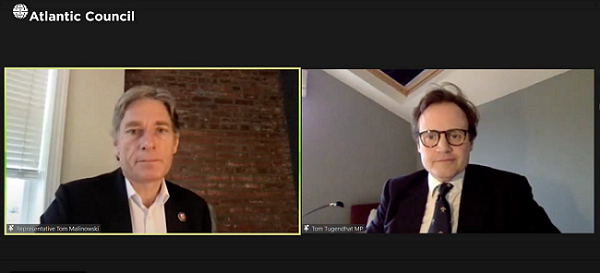

The Free World Commission, which brings together influential legislators from leading democracies, recently held a hearing on the need for a coordinated strategy for China. Legislators can play a meaningful role in to help ensure that a strategy based on shared interests and values is coordinated and aligned across the democratic world.

The challenge of China

China presents a serious challenge to likeminded allies and partners, and to the rules-based system. The challenge from China is evident in the economic, diplomatic, governance, security, and health domains.

- Economic: China engages in unfair economic practices that violate international standards, including: intellectual-property theft, subsidizing state-owned companies to pursue geopolitical goals, and restricting market access to foreign firms. It is also investing enormous state resources in a bid to dominate key technologies of the twenty-first century.

- Diplomatic: Through ambitious plans, such as the Belt and Road Initiative, China is expanding its diplomatic influence in every region and taking aggressive action against countries that resist or criticize Beijing. Its coercive diplomacy, however, is beginning to provoke a backlash.

- Governance: China’s economic and political model of authoritarian state capitalism is the first formidable alternative to the success – full model of open market democracy since the end of the Cold War. Current and would-be autocrats look to China as a model for combining authoritarian control with economic success. Abroad, China is using “sharp-power” tools to disrupt democratic practices and is exporting surveillance technologies that bolster authoritarian governments.

- Security: China continues its decades-long military modernization and expansion, while making sweeping territorial claims and increasing its military and intelligence activities globally. Its growing capabilities increasingly threaten the United States’ collective defense with long-standing allies in the Indo-Pacific and beyond.

- Health: In a failed bid to protect its image, the CCP suppressed information about the novel coronavirus, silenced those attempting to speak out about it, and used its influence in the World Health Organization (WHO) to hamper global efforts to understand, and quickly mitigate, the spread of the virus.

China presents particularly significant challenges to global governance

The CCP’s repressive political model and reliance on nationalism diminish opportunities for cooperation in a rules-based system. Through concerted sharp-power efforts, China has sought to disrupt democracies with disinformation and shape narratives about the CCP. Moreover, it exports technology that autocrats use to control their populations, thereby helping China create a world safe for autocracy.

China, for example, has boosted its position in existing multilateral organizations such as the United Nations, and it has often used that influence to undermine the very purpose of these agencies. While the United States has pulled back from some multilateral bodies, China has focused on winning elections to key leadership positions in multilateral organizations. It is also expanding its influence by increasing its voluntary financial contributions. The most notable recent example is China’s increasing influence in the WHO. In the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, the WHO publicly praised China even as its staff privately complained that China was refusing to share information about the disease. China has also proactively integrated into major standard-setting bodies such as the International Organization of Standardization (ISO) and a broad range of international industry-level forums in which technical standards are developed. China is also reactivating ailing organizations like the Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia (CICA).

In addition, China is engaged in “sharp-power” (or “authoritarian influencing”) efforts to interfere in and manipulate the domestic politics of democracies to Beijing’s benefit. China seeks to mute criticism of, and amplify positive narratives about, China, shape understandings of sensitive issues important to the CCP (such as Taiwan), and covertly influence democracies’ legislation and policies toward China. China supports hundreds of Confucius Institutes throughout the world, including at colleges and universities. China also funds propaganda supplements in prominent publications, such as the Washington Post, and pays lobbyists to promote the CCP’s desired narrative. Chinese state media are boosting their global presence, in part by buying foreign media outlets. A 2019 report by the journalist-advocacy group Reporters without Borders argued China has “actively sought to establish a ‘new world media order’ under its control, an order in which journalists are nothing more than state propaganda auxiliaries.”

Relatedly, China is using its economic power to stifle free speech in democracies. China threatens to retaliate against Western businesses that denigrate China. Through this coercion, the CCP has persuaded Hollywood to change movie scripts involving China, the National Basketball Association to apologize for an executive who spoke out on Hong Kong, and US airlines to remove Taiwan from global maps. China also conducted an arbitrary arrest of two Canadian citizens, in an apparent attempt to pressure Ottawa into releasing Huawei executive Meng Wanghou.

Contrary to traditional diplomatic niceties, Chinese diplomats are increasingly engaging in “wolf warrior diplomacy,” combatively denouncing any criticism of China and aggressively lashing out at critics. For example, Chinese officials have spread conspiracy theories about the virus being brought to China by the US Army. A Chinese diplomat in Paris complained about the French media’s treatment of China, saying it is to “howl with the wolves, to make a big fuss about lies and rumors about China.” Chinese diplomats have also accused French authorities of letting the elderly die in nursing homes. After Australia called for an inquiry into the virus’s origins, China’s state media labeled Australia “gum stuck to the bottom of China’s shoe,” and an ambassador suggested Australia was putting the nations’ trade relationship at risk. Chinese officials also got into a battle with the German newspaper Bild after it called on China to pay billions in compensation to Germany.

The CCP has its ideological roots in Marxism-Leninism and maintains supreme control over the functions of the state and law. Its values, and its often-repressive approach to maintaining power, do not square well with the values of the rules-based international system. Whereas democratic states benefit from sources of legitimacy such as the consent of the governed and attractive values, the CCP relies heavily on nationalism to perpetuate its hold on power. Nationalism rallies political support for the CCP and directs internal energies against external opponents. Furthermore, as CCP ideology has grown increasingly intertwined with capitalism, and has sacrificed its Marxist ideals, nationalism has served as a means of binding the Chinese people together.

Making the world safe for autocracy

Following the Cold War, the Western model of open market democracy was virtually unchallenged on the world stage. Now, there is a formidable competitor in the form of China’s model of authoritarian state capitalism. This Chinese model is proving attractive to many current and would-be autocrats. Indeed, for the past few decades, China has shown it is possible to attain dramatic economic growth within a repressive political framework. As open market democracies in Europe and the United States struggled amid the 2008 financial crisis, China’s economy proved resilient, further increasing its model’s appeal.

Scholars debate whether China is consciously exporting its model. At a minimum, however, it is clear that China wants to create a world safe for autocracy. After all, if democracy spreads to Beijing, the CCP and its officials would be in mortal danger. The CCP has increased restrictions on freedoms at home. This has manifested in heightened repression of religious and ethnic minorities, especially Uighur Muslims in western China, more than one million of whom are in internment camps. The CCP has also cracked down on Hong Kong, passing a sweeping surveillance law designed to prohibit criticism or protest of the party’s authoritarian practices. The CCP is also using advanced technology to develop stronger tools for controlling the Internet in China, bolstering its “Great Firewall.”

Abroad, there is at least some evidence that China is trying to export its model. Through the BRI’s “Digital Silk Road” initiative, China has pushed for national governments to have greater control over the Internet. China is also training governments from Cambodia to Serbia on how to control the flow of information and target individuals who challenge the official narrative. Chinese corporations have provided authoritarian governments in Venezuela and elsewhere with facial-recognition technology and other surveillance tools. These domestic and foreign efforts by the CCP have contributed to democratic decline globally.

Recent actions by leading democracies

In response to Chinese attempts to undermine the norms of the free world, leading democracies have taken action to punish or deter Beijing. These actions have centered primarily around four areas: human rights violations, including imposition of China’s new national security law in Hong Kong and China’s treatment of the Uighurs; China’s actions regarding Huawei and technology-related concerns; freedom of navigation in the South China Sea; and unfair trade practices.

In response to the enactment of the national security legislation by the PRC in Hong Kong, several leading democracies have acted swiftly to counter and punish China, as well as protect Hong Kong citizens. Several nations—Australia, Canada, France, Germany, New Zealand, and the UK—have suspended extradition treaties with Hong Kong; the European Union is currently considering similar actions. In a similar move, the US Department of State suspended three bilateral agreements with Hong Kong covering the surrender of fugitive offenders, the transfer of sentenced persons, and reciprocal income tax exemptions derived from the international operation of ships. The United States has also enacted the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act, which authorizes the sanction of the entire 14 Vice Chairpersons of the National People’s Congress responsible for human rights abuses in Hong Kong. Sanctions activity has not been limited to the United States. In the same period, the European Union has limited exports of equipment China could use for repression and reassessing extradition arrangements in light of Beijing’s national security law. Canada’s Parliament has also called to sanction Chinese individuals and entities in coordinate with democratic allies.

With regard to China’s treatment of ethnic minorities, including the Uighurs, Several nations – France, Germany, the United Kingdom, and Canada – have denounced Chinese diplomats, in a joint letter to the UNHRC. The United States, in a similar move in 2019, closed the Chinese consulate in Houston, and publicly criticized the increased censorship and religious persecution by the Chinese government. Pursuant to the Uyghur Human Rights Policy Act, passed by Congress, the Trump administration imposed sanctions and visa restrictions against senior Chinese officials. In October 2020, a Canadian parliamentary committee said that China’s actions against ethnic Uighurs in Xinjiang province constituted a genocide, and called for sanctions against Chinese officials complicit in the Chinese government’s policy.

In the last three years, democracies have also engaged in efforts to push back Chinese technology companies, in particular Huawei, which raised concerns over Chinese access to sensitive 5G networks. The US Congress, in 2019, passed a law that banned Huawei and ZTE equipment from being used by the U.S. federal government, citing security concerns. The United Kingdom, in July 2020, banned Huawei from its 5G networks by the end of 20217. France and Germany, while still allowing Huawei to operate, passed legislation which gives their governments the ability to outlaw Huawei by citing security concerns and imposing greater regulatory controls.

On freedom of navigation, the United States has vocally criticized China’s claims of sovereignty in the South China Sea, and has engaged in naval operations of ships passing through areas that Beijing claims to be within its maritime jurisdiction. Several other leading democracies have participated in these freedom of navigation operations, including the United Kingdom, Australia, Japan, and France. Recently, Germany joined France and the UK in a joint statement denouncing China’s claims in the South China Sea.

On the economic front, the United States has successfully pursued claims of Chinese unfair trade practices before the WTO, regarding unfair trade practices. The EU earlier this year implemented a new program aimed at pushing back against China’s use state subsidies and predatory acquisitions. Australia firmly denounced China’s “economic coercion” after Beijing’s recent imposition of trade sanctions. Separately, the US, Japan, and the EU have begun a series of trilateral dialogues among trade ministers to discuss cooperation to address Chinese unfair trade practices.

More broadly, the US Congress has taken action to call for closer strategic cooperation between the United States and its allies on China. The US Senate passed legislation calling for a “unified approach and comprehensive strategy with our allies in Asia, Europe, and around the world to combat China’s growing aggression.” More recently, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee released a report in December calling for the United States to work more closely with European partners, the and other market-led democracies to deal with China. In 2019, the British House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee issued a report on China and the rules-based order calling for a coordinated strategy to deal with Beijing. Relatedly, a recent European Union report also called for closer transatlantic collaboration on China.

Goals for a coordinated China strategy

A revitalized and adapted rules-based system will not flourish to its greatest extent if China, the world’s second-largest economic and military power, remains outside the system or is actively attempting to undermine it.

In the long term, likeminded allies and partners should seek a stable relationship with China that avoids permanent confrontation and permits cooperation on issues of mutual interest and concern, and that makes China a cooperative member of a revised and adapted rules-based system. The revised system should respect individual liberties, societal openness, and China’s legitimate interests.

These goals will be difficult to actualize with Xi as president and the current generation of CCP leadership in power. As discussed above, the incorporation of China into the global economic system has not been sufficient to moderate Chinese behavior. Instead, as China has become wealthier and more powerful, Xi and the current generation of leaders have decided to launch China on a new and more assertive course. They are selectively challenging key aspects of the rules-based system and the interests of likeminded allies and partners. These long-term objectives may only be achievable after a generation or more, when new Chinese leaders, with a different worldview, come to power.

To achieve these long-term objectives, therefore, policymakers will need to convince the Chinese leadership to change course.

In the short term, likeminded allies and partners should prevent China from undermining the rules-based system in the security, economic, and governance domains. They should defend their interests and international standards while affording space for and inviting responsible Chinese behavior. This will put them in a stronger position regardless of how China behaves. They must also seek to impose costs on Chinese actions that violate international rules and norms, with the objective of shaping Chinese behavior in a positive direction.

This strategy proposes the following goals:

- Security: Maintain global peace and stability by fostering a favorable balance of military power for likeminded allies and partners capable of deterring and, if necessary, defeating Chinese aggression.

- Economy: Facilitate a global economic recovery and advance global prosperity by maintaining open and market-based economies at home and abroad, while resisting unfair economic practices and the spread of authoritarian, state-led capitalism.

- Governance: Maintain freedom by revitalizing democracy in existing democratic states, preventing CCP efforts to undermine democratic practices, and supporting human rights, democracy, and good governance in other states, including in China.

Elements of a coordinated strategy

To achieve these objectives, this paper proposes a three-part strategy for China. First, likeminded allies and partners should strengthen themselves, their alliances, and the rules-based system for a new, more competitive era. Second, likeminded allies and partners must defend their interests and the rules-based system from the China challenge, and impose costs on the CCP when it violates widely agreed-upon standards. Third, likeminded allies and partners should engage with China from a position of strength to cooperate on areas of mutual interests and, over time.

Element one: Strengthen

Likeminded allies and partners should strengthen themselves and the rules-based system for a new era of great-power competition. Likeminded allies and partners must strengthen themselves, their alliances, and the rules-based system for a new era of great-power competition. By bolstering themselves, likeminded allies and partners will be in a stronger position regardless of the choices made by China’s leaders. They should:

- Facilitate a recovery from the current health crisis and pandemic-induced economic downturn;

- Prioritize innovation and emerging technology by boosting research and development spending, investing in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) education, and securing supply chains;

- Invest in repairing and renewing infrastructure and ensuring it incorporates advanced technology, including fifth-generation (5G) wireless capability;

- Reassert influence in existing multilateral institutions by, for example, promoting candidates for leadership positions that favor upholding open and transparent global governance;

- Create new institutions to facilitate collaboration among likeminded allies and partners in Europe, the Indo-Pacific, and globally; and • develop new military capabilities and operational concepts to achieve a credible combat posture in the Indo-Pacific region

Revitalizing the rules-based international system requires deeper collaboration among democratic nations, expanding and deepening partnerships to new nations beyond this traditional core, and promoting democracy and free markets by example.

Deepen collaboration among democratic nations at the core

The advanced, consolidated democracies of Europe, North America, and the Indo-Pacific should deepen their collaboration to address shared challenges and seek new opportunities. These nations formed the core of the previous rules-based system, and they will need to continue to play that role as the rules-based system is revitalized and adapted for new challenges. Strengthening this platform at the heart of the rules-based system will put these states and the world in a stronger position, regardless of how China behaves. Moreover, it will enable them to better manage the China challenge. Beijing prefers to divide these nations and address them one at a time. The nations of the free world will be better able to confront and engage Beijing if they present a unified front.

Strengthen diplomatic cooperation within the free world

Meeting the China challenge will require new structures and processes for consultation and coordination among democratic partners. Globally, the world’s leading democracies increasingly face similar challenges, including from the rise of China. Accordingly, leading democracies across Europe, North America, and the Indo-Pacific are working together more than in the past. When they pool their collective resources and influence, these states can have a decisive influence on global outcomes. Too often in the past, however, intra-democratic coordination has occurred on an ad hoc basis. Establishing more formalized processes and institutions for democratic collaboration globally can reduce these transaction costs, strengthen habits of democratic cooperation, and more effectively implement a combined free-world strategy for China.

The free world should elevate and expand the G7 to a D-10 grouping of leading democracies. The D-10 should include the current members of the G7, but grow to include leading democracies in Asia, including Australia and South Korea (and possibly India). The D-10 should take on a broader range of responsibilities beyond the global economy to include global security and governance. The D-10 should function as a steering committee of the democratic core of the rules-based international system. It should be the main platform for democratic states to come together, forge shared threat assessments, and develop common strategies for a broad range of issues, including China.

Reassert influence within multilateral institutions

Likeminded allies and partners must reassert their influence in the multilateral institutions of the UN-based system. These leading democracies were instrumental in creating and utilizing these bodies, such as the World Trade Organization (WTO), the WHO, and the Human Rights Council (HRC). In recent years, however, China has engaged in “competitive multilateralism” to gain influence within these organizations and undermine their founding missions. In response, some in the West advocate abandoning these institutions. Instead, the free world should also engage in competitive multilateralism. Even as the free world establishes the new bodies called for above, the legacy UN institutions will continue to exist and play an important role. Moreover, because of their international legal status and global membership, they will continue to enjoy broad international legitimacy. It would be a mistake to cede authority in these bodies to hostile states. Rather, the free world should reaffirm its support for these bodies, maintain or increase funding levels, put forward candidates for leadership positions, and ensure that these bodies carry out their historic mission. Moreover, these multilateral institutions can become an important arena for both contesting China and seeking engagement on issues of shared interest.

Strengthen economic cooperation within the free world

Likeminded allies and partners should strengthen economic cooperation within the free world in the areas of trade, technology, and infrastructure. Through enhanced economic cooperation, they can strengthen the prosperity of their people and their states’ economic capacity. This will bolster their soft and hard power for the coming competition with China. Moreover, due to their economic heft, international economic standards set by the leading democracies will become the global standards that China must accommodate.

Strengthened economic cooperation begins with a recommitment to free and fair trade. The free world should work toward a global Free World Free Trade Agreement. The agreement could stitch together the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement with the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP). As intermediate steps, the United States should rejoin CPTPP and negotiate new trade deals with the United Kingdom (UK) and the EU. In addition to enhanced prosperity, these agreements will help standardize global rules on intellectual property, subsidies, labor, and the environment.

Likeminded allies and partners should also work together to reform the WTO to account for and prevent predatory Chinese behavior while, at the same time, including China in the reformed structure. They should reform the criteria for “developing-country” status to exclude China, the world’s second-largest economy. They also need to reform the dispute-settlement mechanism so that disputes can be adjudicated more rapidly, and strengthen enforcement against prohibited practices such as subsidies for state-owned enterprises. Rather than allow this pillar of the post-World War II global economic order to falter, the free world can take these steps to adapt it to modern needs, secure robust global trade governance, and create a powerful platform to confront China’s unfair trade practices.

Expand technology cooperation

Likeminded allies and partners should also work together to sharpen their technological edge. In the new-tech arms race, China has the advantage of scale against any of its competitors alone, but this advantage would be dwarfed when confronted with a coordinated free-world approach to technological development and standard setting. Likeminded allies and partners should create a D-10 technology alliance. The United Kingdom has proposed just such a body. A D-10 technology alliance could conduct joint research and development and could pool resources, such as data for AI development. It could coordinate on matters concerning the leakage of sensitive technology to China by developing common approaches to restricting Chinese investment in technology sectors and developing export controls. This body could also work together to develop common guidelines on Huawei 5G infrastructure in likeminded countries and cultivate alternative producers of 5G technology in the free world. The Open Radio Access Network (Open RAN) is a promising concept to guide these efforts. Likeminded countries could diversify supply chains for critical materials such as rare-earth minerals. This body could also establish global norms for developing and using emerging technologies, including the responsible uses of artificial intelligence, surveillance, autonomous vehicles, and smart cities.

Foster infrastructure development

Likeminded allies and partners should also increase infrastructure investment in the developing world. These projects would serve as an alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative. While these leading democracies may not wish to match China’s public lending, they can unleash their private sectors. They should encourage and incentivize private-sector lending in Asian infrastructure. They can strike investment treaties and use public funding to spur private investment in projects abroad. They should help Indo-Pacific nations implement economic and legal reforms to make them more attractive to foreign investors. They should also devote more resources toward connecting private companies with opportunities in the Indo-Pacific. While some recipient countries see China’s no-strings-attached approach to lending attractive, leading democracies should emphasize the benefits of their approach, which encourages the growth of effective government and economic institutions, and maintains high standards for transparency, anti-corruption, the environment, and labor protections. Likeminded allies and partners should also accept Beijing’s invitation to join the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank in order to improve its lending standards and counter China’s influence in the body.

Strengthen security cooperation within the free world

Likeminded allies and partners should increase cooperation in the security sphere. In the past, US alliance networks were arranged regionally, but China presents a global challenge and democracies globally, worried about China’s rise, should form new security architectures. Under these new arrangements, they should conduct joint threat assessments of the China challenge and develop common defense and military strategies and capabilities. Rather than thinking of these alliances as a mechanism by which the United States provides security to its allies, leading democracies should work together to contribute to a joint defense of the free world.

The D-10 should become a primary venue for global security cooperation among likeminded allies and partners. Sharing of intelligence assessments should be a high priority within the D-10, as a precursor to more ambitious intelligence-sharing and security-cooperation arrangements.

In the Indo-Pacific, likeminded democracies should form a multilateral alliance to deal with the China challenge. Already, “the Quad” of Australia, India, Japan, and the United States serves as a forum of nations looking to counter China in that region. They should build on this and form a broader, formal or informal, organization of security partners in the Indo-Pacific. Likeminded allies and partners in the region should put aside or resolve disputes among themselves, especially Japan and South Korea, both of which have seen relations decline in recent years. A strong trilateral relationship is necessary for cooperative efforts to counter China.

The China security challenge is global, however, and Transatlantic security organizations also have a role to play. NATO should work with Asian allies to coordinate security and defense strategy. NATO has already established partnerships with Australia, Japan, Mongolia, New Zealand, and South Korea. It should build on these efforts to become a forum for NATO and non-NATO allies to share intelligence and assessments on China’s activities and capabilities. NATO should also play a greater role in freedom-of-navigation operations with Pacific partners. As will be discussed in more detail below, NATO could also issue declaratory statements, backed with threats of concrete repercussions, aimed to deter armed Chinese armed aggression against its neighbors.

An Alliance of Free Nations

There are many other leading democracies that could be brought into this coalition, including Sweden, Indonesia, Brazil, South Africa, and others. In addition to the D-10, therefore, the world’s leading democracies should also establish a new formal entity: an Alliance of Free Nations (AFN), or Alliance of Democracies. Whereas the D-10 is limited to a small core group of like-minded states, AFN membership would be open to all recognized democracies around the world—large and small—committed to the shared principles of a rules-based system. AFN founding members will need to define clear criteria for membership in this club of democracies. In doing so, they should draw on widely accepted guidelines for ranking democracies, such as those prepared by Freedom House. The AFN would serve as a platform for strategic cooperation on the world’s most pressing challenges. The AFN would align the collective resources of its members, and facilitate burden sharing and allocation of responsibilities. The AFN would serve as a body for consultation among democracies for addressing major strategic challenges to the rules-based system, including those posed by China. These common threat perceptions can form the basis for an effective alliance. As a first step toward this goal, the world’s democracies should convene in a major Summit for Democracy.

Promote open market democracy

Likeminded allies and partners should strengthen the rules-based system by promoting democracy and free markets. Over the past several decades, the rules-based system has benefited from a large number of free-market democracies. Despite their imperfections, these systems have proven better than any other at delivering human dignity, prosperity, and human flourishing. Democratic countries with market economies are more likely to join and comply with the institutions of the rules-based system. For decades, the United States and other leading states advanced a rules-based system by encouraging political and economic liberalization in other states. In a period in which these principles are being challenged by the rise of authoritarian-state-led capitalism and democratic backsliding, leading states should not back away from these principles as some have argued; rather, they should reinforce them.

Leading states should use all the available tools in their toolkit to strengthen open-market democracies. This should include supporting civil-society groups, providing access to information in closed societies, and bolstering institutions in fledgling democracies. They should use conditionality to tie security arrangements and economic assistance to reforms in partner and recipient countries. They should also use public diplomacy to advance positive narratives about the leading democracies, as well as countering disinformation and challenging misleading narratives put forth by China.

Element two: Defend

In addition to strengthening themselves to compete with China, likeminded allies and partners must be prepared to defend themselves and the rules-based international system from threatening Chinese behavior. Across the security, economic, and governance domains, they should counter China and impose costs on Beijing when it violates international standards. They should:

- Prohibit Chinese engagement in economic sectors vital to national security; • collectively impose offsetting measures, including tariffs, for industries negatively affected by China’s unfair practices;

- Collectively resist Chinese economic coercion by reducing economic dependence on China and offering offsetting economic opportunities to vulnerable allies and partners;

- Counter Chinese influence operations and defend democracy and good governance;

- Coordinate penalties on China when it uses coercive tools, such as arbitrary detention of foreign nationals, to pressure their home countries;

- Spotlight CCP corruption and human-rights violations and encourage human-rights reforms in China; and

- Maintain a favorable balance of power over China in the Indo-Pacific to deter and, if necessary, defend against Chinese aggression.

Likeminded allies and partners should put in place measures to defend against Chinese interference in their societies, to protect democracy, and to impose costs on the CCP for its gross human-rights violations.

Counter Chinese “sharp-power” practices

Likeminded allies and partners should launch a coordinated campaign to counter Chinese influence operations. In doing so, they should raise public awareness of the threat posed by the Chinese Communist Party, while avoiding the alienation of, and discrimination against, people of Chinese origin. In multicultural democracies, resisting CCP interference is about protecting the rights of all citizens—not least those of Chinese origin—to express their views without foreign intimidation.

The first step is greater awareness. Democratic governments should direct their intelligence agencies to conduct a systematic review of China’s foreign-influence operations in their countries. Likeminded allies and partners should share intelligence on China’s efforts. They should require disclosures of foreign-government funding of think tanks, civil-society institutions, educational institutions, and politicians. For instance, Chinese state-run and state-funded press outlets should be required to label their products with clear disclaimers that the CCP paid for the content. Likeminded allies and partners should also require disclaimers on any foreign-government propaganda.

Next, appropriate punishments against the CCP and those in collusion with it should be designed. Institutions receiving CCP funding may face punishments including the loss of their nonprofit status or corresponding cuts in domestic government support. Confucius Institutes should be shuttered in the free world. While posing as cultural organizations, Confucius Institutes have, in fact, served as an arm of the CCP, intimidating students and controlling what academics can and cannot publish. Likeminded allies and partners should demand reciprocity with regard to the operations of foreign intelligence services and be willing to prosecute or expel Chinese officials who violate national rules. Likeminded allies and partners should coordinate penalties on China if it uses coercive tools such as arbitrary detention of foreign nationals to coerce their home countries.

Impose a cost on the CCP for its gross human rights practices

The free world should hold China accountable for its gross human-rights practices. It should shine a spotlight on China’s ethnic cleansing in Xinjiang and Tibet, its crackdown on democracy in Hong Kong, and its treatment of political prisoners, such as human-rights lawyers, citizen activists, and Falun Gong practitioners. This should be among the priority topics of discussion in public and private diplomatic engagements with the CCP. Officials responsible for these policies should face sanctions, including asset freezes and travel bans for them and their families.

Likeminded allies and partners should also take steps to directly improve freedom and human rights within China. They should provide support to civil-society groups and promote access to independent media and information for the Chinese people. This would begin by prohibiting Western companies from assisting the CCP in erecting the “Great Firewall.” More boldly, it could include cyber operations to disable or circumvent the “Great Firewall.” Likeminded allies and partners should strive to engage with Chinese dissidents and activists without putting them in danger. This could include meeting with Chinese dissidents living in allied and partner countries, highlighting unjustly imprisoned activists and encouraging their release, and using public-diplomacy news outlets such as Voice of America to produce more Chinese-language content that identifies crimes by the CCP and amplifies dissidents’ voices.

Counter the CCP’s autocracy promotion

The free world should work together to thwart China’s attempts at stifling freedom and human rights abroad. It should proudly contrast and promote the record of its successful model of open market democracy in comparison China’s authoritarian, state-led capitalism. Likeminded allies and partners should develop a unified approach to highlighting and resisting Chinese efforts to use threats of economic punishment to stifle free speech in the free world that is critical of China. They should impose sanctions on the Chinese individuals and firms involved in exporting advanced surveillance technology to autocratic governments around the world.

Element three: Engage

Likeminded allies and partners should engage China from a position of strength to cooperate on shared interests. They should:

- Maintain open lines of communication with China, even if competition intensifies;

- Seek to cooperate with China on issues of mutual interest, including public health, the global economy, nonproliferation, and the environment, without compromising core values; and

- Engage with China to, over the long term, incorporate China into a revitalized and adapted rules-based system.

Over time, likeminded allies and partners should seek to work with China to help it become a cooperative member of a revitalized and adapted rules-based system. This can be accomplished by attempting to engage China to join in designing the rules of the system. The areas of greatest opportunity are in domains in which the rules are not yet clearly defined, such as emerging technology, space, and cyberspace. These discussions may be difficult at first and may not gain much, if any, traction initially, but they may be worth the effort if the end result is a revitalized and adapted rules-based system that includes the world’s second-largest economic and military power as a cooperative member.

Technology cooperation

Likeminded allies and partners should engage China on developing common standards for emerging technology. This should include frameworks for the responsible use of AI. In the military domain especially, the United States and China should discuss the ethical boundaries of these technologies. Furthermore, likeminded allies and partners and China should explore opportunities to collaborate on developing applications of AI that are mutually beneficial, such as for healthcare. AI has useful applications for diagnosing illnesses and discovering cures and treatments, which could be furthered via cooperation. AI can also be applied to monitoring climate change, increasing energy efficiency, and other issues on which all countries stand to gain from working together.

Moreover, in recent years, the Internet has begun dividing into competing spheres. Whereas China favors Internet governance rooted in national sovereignty and close control of information flows, likeminded allies and partners favor an open, accessible, freer model for the Internet. The CCP is pushing for its model in multilateral forums, while Chinese corporations bolster the ability of other autocracies to control the Internet. The BRI also contains a “Digital Silk Road” initiative geared toward exporting China’s model of managing the Internet. Likeminded allies and partners should resolve their own differences regarding Internet governance and engage China on cyberspace in multilateral forums to develop clear global frameworks for the Internet. China is also rapidly increasing its space presence in both the civil and military domains. It has more than one hundred and twenty intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) satellites—only the United States has more. China’s space capabilities threaten Western satellites used for communication, navigation, and ISR, and China continues to invest heavily in counterspace technology.

Space cooperation

As China has boosted its activity in space, the United States has engaged Beijing in bilateral talks about space-related issues. The two countries should repeat and continue the Space Security Talks and engage on issues of space sustainability and civil space cooperation by continuing the US-China Civil Space Dialogue. Likeminded allies and partners and China should also work to develop global norms for outer space, geared toward reducing orbital debris and developing confidence-building measures to clarify perceptions and diminish the risk of conflict in space.

A new Helsinki process

More broadly, likeminded allies and partners should seek to engage Chinese officials to formulate a common vision for a broader, more inclusive rules-based system based on mutually acceptable rules and norms. Chinese leaders often profess to support principles of a rules-based system, and Beijing has made commitments through treaties and agreements to uphold international norms. Drawing inspiration from the Helsinki Process, the goal of these talks should be to negotiate and adopt a new charter of principles for an adapted rules-based system.

To be sure, Beijing may be wary given the Helsinki Process’s role in prompting greater openness in the Soviet Union. Through creative engagement, however, China may see the benefits of discussions on a new charter of common principles for a rules-based system. This process would provide an outlet for China to pursue its legitimate interests in ways that are consistent with international norms. Of course, it is possible that Beijing could simply sign on to a charter of principles as a propaganda effort without any real intention to abide by them. Nevertheless, by incentivizing Beijing to make such commitments, likeminded allies can use such a charter to hold China to account for violations of such norms. They could link cooperation in certain areas, such as in trade, to Beijing’s compliance with commitments to uphold human rights norms. Over time, the hope would be that the Chinese government would fully embrace the norms and principles espoused in the charter.

Role of the Free World Commission

The free world has an impressive record of accomplishment in defeating challenges from autocratic great-power rivals and constructing a rules-based system. By pursuing this strategy—and with sufficient political will, resilience, and solidarity—they can once again outlast an autocratic competitor and provide the world with future peace, prosperity, and freedom.

The Free World Commission is composed of influential legislators from leading democracies committed to defending democracy and advancing a rules-based international order. The Commission includes the foreign affairs committee chairs and/or other influential legislators representing Australia, Canada, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States, as well as the European Union. The Commission was established by the Atlantic Council with a grant from the National Endowment for Democracy, and conducted its first public hearing at the Munich Security Conference in February 2020.

More recently, in December 2020, the Commission held its second public hearing virtually, with a focus on the challenge of China and the need for a coordinated strategy among leading democracies. The Commission heard from several former senior officials, including from the United States, Canada, and Germany, on challenges posed by China and opportunities for greater collaboration.

The Free World Commission can play an important role in helping to coordinate the passage and implementation of legislative actions regarding China’s challenge to the rules-based democratic order. This could include introducing parallel measures in their respective parliaments to ensure that collective action is taken by governments. Through coordinating joint statements and legislative actions, Commission members can demonstrate democratic solidarity regarding China and encourage national governments to coordinate more closely on a strategy for China aimed at advancing a rules-based order based on shared values and interests.

Image: Primary school students hold a giant Chinese flag as they perform a song titled "Me and my country" during an event at the start of a new semester in Handan, Hebei province, China September 1, 2019. REUTERS/Stringer ATTENTION EDITORS - THIS IMAGE WAS PROVIDED BY A THIRD PARTY. NO COMMERCIAL OR EDITORIAL SALES IN CHINA