The murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi thrust an otherwise little-known sanctions program into the spotlight—the Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act (or GloMag in sanctions parlance). On November 15, the US Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control used the GloMag authority to designate seventeen Saudi citizens for their role in the Khashoggi killing.

The murder of Jamal Khashoggi thrust an otherwise little-known sanctions program into the spotlight, and cast overdue attention on this important authority—the Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act (or GloMag in sanctions parlance).1Vick, Karl, “How the Murder of Jamal Khashoggi Could Upend the Middle East” Time, 18 October 2018, http://time.com/5428159/jamal-khashoggi-murder/ Irrespective of whether the Trump administration chooses to use this authority on individuals in the Saudi leadership in response to the apparent premeditated murder of Khashoggi, GloMag offers a targeted response for such a foreign policy concern.2Sanchez, Raf, “Saudi Arabia Changes its Story Again and Says Jamal Khashoggi Was Killed in ‘Premeditated’ Murder” The Telegraph,. 25 October, 2018. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2018/10/25/saudi-arabia-says-jamal-khashoggi-killed-premeditated-murder/ However, the merits and implications of GloMag should be considered far more broadly than in the shadow of the Khashoggi murder.

GloMag has the potential to help raise the bar on global human rights and anti-corruption standards, provided it continues to be used effectively and is capitalized on appropriately. This sanctions authority has far-reaching implications for international businesses, as it warrants a paradigm shift in their risk calculations. GloMag sanctions create the need for businesses to shift to a proactive corporate risk and due diligence strategy that takes into account both human rights and corruption issues. For allies, partners, and the array of international human rights groups seeking to raise awareness of human rights violations and corruption, this sanctions authority creates an opportunity for partnership and multilateral sanctions actions.

What is the Global Magnitsky sanctions authority?

In late December 2016, Congress passed the Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act to limited fanfare.3“National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2017” Public Law 114-328. 130 STAT. 2000 (2016). https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/senate-bill/2943/text This was the second law named for Russian whistleblower Sergei Magnitsky, who died while in Russian prison after being tortured and denied medical care.4Lally, Kathy, “U.N.-Appointed Human Rights Experts to Probe Death of Russian Lawyer Magnitsky” Washington Post Foreign Service, 20 January 2011. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2011/01/20/AR2011012003237.html?nav=emailpage The newer law builds upon the original Magnitsky Act by expanding the scope of the authority for economic sanctions and visa bans related to human rights abuses and corruption to global actors.5‘‘Russia and Moldova Jackson-Vanik Repeal and Sergei Magnitsky Rule of Law Accountability Act of 2012’’ Public Law 112-208. 126 STAT. 1496 (2012). https://www.congress.gov/bill/112th-congress/house-bill/6156/text?q=%257B%2522search%2522%253A%255B%2522sergei+magnitsky+rule+of+law+accountability+act%2522%255D%257D&r=3 This is a significant broadening since the original Magnitsky act was focused solely on Russia.

Congress recently called on the Trump Administration to apply the GloMag authority to the top leaders of the Saudi government in response to the Khashoggi murder, though the administration is unlikely to comply.6Temple-West, Patrick, “Republicans and Democrats Find Common Foe: Saudi Crown Prince” Politico, 21 October 2018. https://www.politico.com/story/2018/10/21/congress-saudi-arabia-khashoggi-921366 This is due, in part, to differing interpretations of the GloMag authority, but primarily because of President Trump’s transactional view of the US-Saudi relationship. If President Trump’s delayed, calculated response to the Khashoggi murder is any indication, the administration will likely target any sanctions at politically palatable ranks of the Saudi government, such as the eighteen people the Saudi government has already arrested—if it chooses to use sanctions at all.7Sink, Justin. “Amid Skepticism, President Trump Praises Saudi Response on Jamal Khashoggi’s Death” Time. 20 October 2018. http://time.com/5430174/trump-praises-saudi-arabia-death-jamal-khashoggi/ and “‘Suspects detained in Khashoggi case will be prosecuted in Saudi Arabia’” Hurriyet Daily News, 27 October 2018. http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/turkey-prepares-extradition-request-for-18-saudi-suspects-138324 Targeting Saudi leadership, including Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, as some in Congress have advocated, seems unlikely given President Trump’s response thus far.8See Politico. https://www.politico.com/story/2018/10/21/congress-saudi-arabia-khashoggi-921366

Taking a step back from the Khashoggi case, the GloMag sanctions authority is robust enough to address dynamic diplomatic situations, including the current one involving Saudi Arabia. This dynamism is due to the expanded designation criteria that technocrats in the executive-branch crafted for the related executive order (E.O.). The expansion included broadened designation criteria to more fully and flexibly target human rights abusers and corrupt actors globally, and to update definitions beyond the dated terms that Congress used in the legislation. The result was E.O. 13818, Blocking the Property of Persons Involved in Serious Human Rights Abuse or Corruption, which the Trump administration issued in December 2017.9Exec. Order No. 13818, 3 C.F.R. 1 (2017). https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/executive-order-blocking-property-persons-involved-serious-human-rights-abuse-corruption/ Unlike under most other economic sanctions programs, this new E.O. does not require the declaration of a national emergency with respect to a specific country, thereby allowing for more calibrated— and perhaps more politically palatable—sanctions. In fact, it is due to the strategic nature of this E.O. that the US Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) has been able to designate more than eighty individuals and entities pursuant to the GloMag authority in less than one year.

Business implications: shifting the sanctions risk paradigm

Given the broad designation criteria under GloMag, international businesses would do well to adjust their corporate risk and due diligence practices to take human rights and kleptocracy issues into account. Businesses have historically taken a reactive stance regarding individual, list-based sanctions that are similar in structure to GloMag, as the regulatory requirements to freeze accounts and cease business with sanctioned targets only take effect once a name is added to a list. This approach is insufficient in the GloMag context. Instead, businesses should take a proactive approach to avoid the risk of future entanglements or violations.

For example, the inaugural GloMag sanctions included international businessman and billionaire Dan Gertler for his corrupt business practices. Gertler amassed an extensive fortune through corrupt mining and oil deals in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) worth hundreds of millions of dollars, in large part due to his close friendship with DRC President Joseph Kabila.10United State Department of the Treasury, “United States Sanctions Human Rights Abusers and Corrupt Actors Across the Globe,” 21 December 2017. https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm0243 The people of the DRC lost more than $1.36 billion in revenue from the underpricing of mining assets that were sold to Gertler’s offshore companies. Those same deals contributed substantially to the International Monetary Fund’s decision to withhold a $225 million loan disbursement to the DRC government.11Wild, Fraz, Micheal Kavanagh, and Jonathan Ferziger, “Dan Gertler Earns Billions as Mine Deals Fail to Enrich Congo” Washington Post, 29 December 2012. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/dan-gertler-earns-billions-as-mine-deals-fail-to-enrich-congo/2012/12/27/c37d0100-4e31-11e2-8b49-64675006147f_story.html?utm_term=.817f46975ce7 They did not, however, dissuade companies such as US hedge fund Och-Ziff, Anglo-Swiss multinational commodity trader Glencore, or South African miner Randgold from doing business with Gertler.12“Gertler Received and Distributed Millions in Bribes in Connection to DRC Mining Deals, Court Papers Allege” Global Witness, 10 August 2018. https://www.globalwitness.org/en/blog/gertler-received-and-distributed-millions-bribes-connection-drc-mining-deals-court-papers-allege/ and Doherty, Ben. “Everything You Need to Know About Glencore, Dan Gertler and Their Interest in DRC”The Guardian., 5 November 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2017/nov/05/what-is-glencore-who-is-dan-gertler-drc-mining

* The two Turkish individuals that were designated under Global Magnitsky authorities in August were delisted on 2 November 2018.

The December 2017 sanctions on Gertler put those business decisions in sharp contrast. By that point, Glencore owed Gertler nearly $200 million in royalties over the next two years, but GloMag sanctions on Gertler made such payments difficult to execute, and could put Glencore at risk of being sanctioned itself for its dealings with Gertler.13“The Global Magnitsky Effect” Resource Matters, February 2018. https://resourcematters.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Resource-Matters-Magnitsky-in-Congo-Impact-of-Gertler-sanctions-16-Feb-2018-FINAL.pdf Glencore has reportedly been cautiously seeking to make the outstanding payments in other currencies, but faces great risk even if it does.14Lewis, Barbara, “Glencore Settles with Gertler Over Congo Royalties” Reuters, 15 June 2018. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-glencore-congo/glencore-settles-with-gertler-over-congo-royalties-idUSKBN1JB0JM Because the US dollar is the main currency used in the DRC and in the global raw materials trade, the sanctions will likely add transactions costs as well as risks. Randgold has reportedly taken a more cautious approach than Glencore and is seeking to cut ties with Gertler.15Wilson, Tom, “Randgold Moves to Cut Ties With Dan Gertler After U.S. Sanctions” Bloomberg, 5 February 2018. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-02-05/randgold-moves-to-cut-ties-with-dan-gertler-after-u-s-sanctions This will surely hurt Randgold’s investments in the projects and may dampen future revenues.

International businesses would do well to adjust their corporate risk and due diligence practices to take human rights and kleptocracy issues into account.

There are a few key takeaways from the Gertler sanctions. First, international businesses need to proactively investigate their partners and clients, and can no longer assume that corrupt businessmen close to ruling governments can operate with impunity. Businesses should proactively adopt due diligence standards to better research how prospective partners or clients amassed their status and/or fortune, and in what type of business practices they previously engaged. Accusations of untoward behavior cannot be discounted based on potential revenue or other benefits from a contract.

Second, beyond the prospective direct partner, businesses should consider the partner’s network in any business calculation. Due to OFAC’s 50 percent rule, any company owned 50 percent or more by a designated individual or entity, such as Gertler, is also considered blocked irrespective of whether the company is specifically included on OFAC’s Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons (SDN) List.16United States Department of the Treasury, “OFAC FAQ: Entities Owned by Persons Whose Property and Interest in Property are Blocked (50% Rule)” US Treasury, https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/faqs/Sanctions/Pages/faq_general.aspx#50_percent As such, a transparent understanding of a company’s ownership structure should be a requirement prior to any investment or purchase. Anyone who continues business with an SDN, like Gertler, despite sanctions risks being the subject of an OFAC enforcement investigation or sanctioned themselves. As the Gertler sanctions illustrate, the United States may use the GloMag sanctions tool at any time with immediate repercussions, including significant reputational risk.

Finally, corruption internationally should concern reputable US and global businesses before it directly affects them. While sanctions on Dan Gertler, and now his thirty-three associated companies and one associate, may seem entirely detached from the West, the cobalt, gold, iron ore, and copper that Gertler’s companies mine are not.17See Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/dan-gertler-earns-billions-as-mine-deals-fail-to-enrich-congo/2012/12/27/c37d0100-4e31-11e2-8b49-64675006147f_story.html?utm_term=.817f46975ce7 And United States Department of Treasury “Treasury Sanctions Fourteen Entities Affiliated with Corrupt Businessman Dan Gertler Under Global Magnitsky” US Treasury, 15 June 2018. https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm0417 For example, demand for cobalt is surging, due to growing global interest in electric vehicles and increasing government restrictions on pollution and engine standards, particularly in Europe. To accommodate this growing demand, Gertler’s companies invested in the mining infrastructure in the DRC, which holds the world’s largest cobalt resources. The overwhelming reliance on the DRC exposes the entire cobalt supply chain to disruption, according to energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie.18Montgomery, Gavin, “The Rise of Electric Vehicles and the Cobalt Conundrum” Wood Mackenzie, 25 September 2018. https://www.woodmac.com/news/editorial/the-cobalt-conundrum/ This disruption may reverberate back across the Atlantic Ocean to impact the price of the Tesla Model 3, Prius, or other electric vehicles and batteries in the United States. If the reputational risk of supporting corruption does not increase businesses’ attention to this issue, the potential financial costs and supply chain disruptions should.

While reputable international companies were likely engaging in basic due diligence prior to the introduction of GloMag sanctions, this sanctions authority should prompt a significantly higher bar by which prospective business deals and client relationships are measured. The cost of such increased due diligence is certainly less than that of the economic and reputational impacts of GloMag sanctions.

Expanding the impact

It is ironic that an administration that chose to withdraw from the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHCR) and has sharply criticized the International Criminal Court (ICC) is trumpeting human rights in the GloMag context.19Owen Bowcott, Oliver Holmes, and Erin Durkin, “John Bolton Threatens War Crimes Court with Sanctions in Virulent Attack” The Guardian, 10 September 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2018/sep/10/john-bolton-castigate-icc-washington-speech The Trump administration’s use of GloMag to advocate for human rights and the need to root out corruption, even if it is entirely on US terms, has made GloMag sanctions an increasingly attractive tool. In fact, some of the same human rights organizations that criticized the administration for its UNHCR withdrawal are advocating for the use of GloMag sanctions.20“NGOs Identify Human Righrs Abusers, Corrupt Actors for Sanctions Under US Bill” Human Rights First, 13 September 2017. https://www.humanrightsfirst.org/press-release/ngos-identify-human-rights-abusers-corrupt-actors-sanctions-under-us-bill

On the diplomatic side, the GloMag authority presents an opportunity for allies to take bilateral actions against targets involved in human rights abuses or corruption. In fact, in February the Canadian government followed the US lead and imposed sanctions on Burmese military leader Maung Maung Soe for his role in the atrocities against the Rohingya in Burma.21Sevunts, Levon, “Canada Imposes Sanctions on Myanmar General Over Rohinga Abuses” CBC, 16 February 2018. https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/myanmar-general-sanctions-canada-1.4539003 (Maung Maung Soe was designated by the United States in the inaugural GloMag designations in December 2017.22United States Department of the Treasury, “United States Sanctions Human Rights Abusers and Corrupt Actors Across the Globe” US Treasury, 21 December 2017. https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm0243) The European Union followed suit in June and expanded the sanctions to include six additional targets, most of whom were also designated by the United States under the GloMag authority a few weeks later.23Press Office General Secretariat of the Council, “Myanmar/Burma: EU Sanctions 7 Senior Military, Border Guard and Police Officials Responsible For or Associated With Serious Human Rights Violations Against Rohingya Population” Council of the EU, 25 June 2018. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2018/06/25/myanmar-burma-eu-sanctions-7-senior-military-border-guard-and-police-officials-responsible-for-or-associated-with-serious-human-rights-violations-against-rohingya-population/pdf and United States Department of the Treasury, “Treasury Sanctions Commanders and Units of the Burmese Security Forces for Serious Human Rights Abuses” US Treasury, 17 August 2018. https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm460 These coordinated actions magnified the plight on the Rohingya far more effectively than a unilateral measure could.

While a number of other OFAC-administered sanctions programs—such as the Iran and Russia programs—carry significant political sensitivities with allies, combatting human rights abuses and corruption are two areas of general policy consensus. That consensus is even stronger when the focus is on human rights abuses alone; this is one area of sanctions policy in which US allies and partners can generally identify shared objectives and agree on targets. It is ripe for replication in allies’ domestic legislation, particularly in countries like Australia, Japan, and New Zealand, as well as within the European Union and across Europe. (The Canadian government already has the Justice for Victims of Corrupt Foreign Officials Act, which is a good first step.24Government of Canada, “Canada Imposes Targeted Sanctions in Response to Human Rights Violations in Myanmar” Global Affais Canada, 16 February 2018. https://www.canada.ca/en/global-affairs/news/2018/02/canada_imposes_targetedsanctionsinresponsetohumanrightsviolation.html) Creating a global human rights sanctions authority would allow for bilateral and multilateral sanctions actions that would strengthen the impact of any GloMag sanctions.

International nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and human rights groups are also helping to magnify the impact of GloMag sanctions. A group of more than twenty NGOs joined together to streamline submissions for consideration by OFAC under the GloMag authority.25Alexandra Oliviera and Alison Spann, “Human Rights Groups Withdraw Government Complaint Against Ukrainian Oligarch After its Accuracy is Challenged” The Hill, 21 December 2017. https://thehill.com/365943-human-rights-groups-withdraw-government-complaint-against-russian-oligarch-after-its-accuracy Additional NGOs continue to individually submit suggested names and supporting information.26Lysove, Ekaterina, “Private Sector Participation in the Global Magnitsky Act” Center for International Private Enterprise, 16 May 2018. https://www.cipe.org/blog/2018/05/16/private-sector-participation-in-the-global-magnitsky-act/ The partnership with the NGOs, many of which are on the ground in places around the world that are ripe for a US government response or engagement, provides the US government with an additional source of reporting on potentially sanctionable activity. Thus far, the administration appears to be using this information and its international partnerships to bolster the GloMag authority with consequential actions.

Maintaining the meaningful balance

GloMag sanctions stand to be a powerful sanctions tool, provided the tool is wielded in a thoughtful and effective manner. A few considerations will help maintain the integrity and value of the GloMag authority, namely:

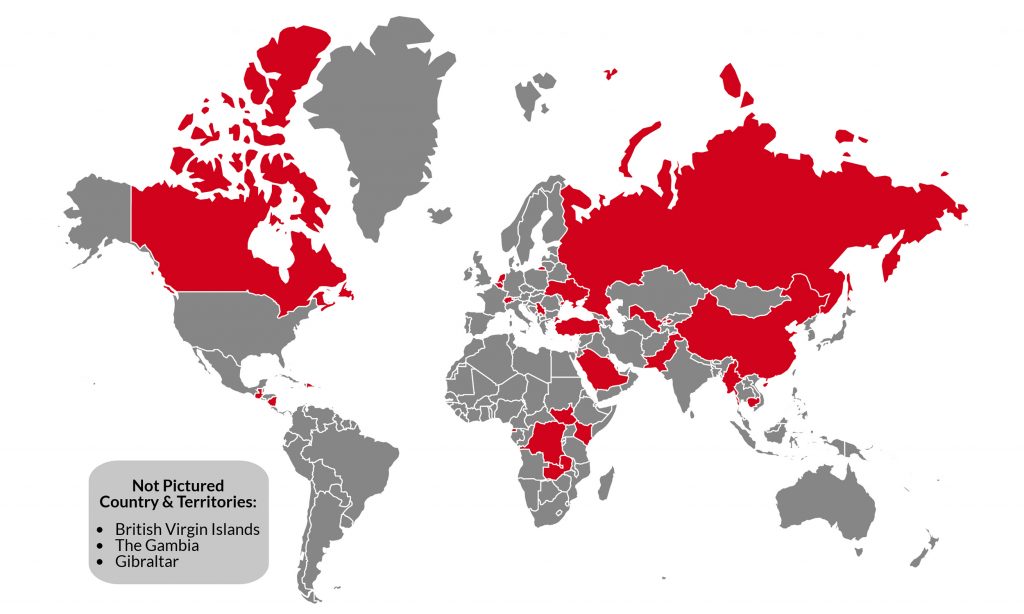

- Maintain the global footprint. The first tranche of GloMag sanctions reflected the global challenge of human rights abuses and corruption. The subsequent designations have generally maintained this global scope. A shift toward one country or region risks undermining the global nature of the authority and minimizing the deterrent effect previous designations have had, particularly in any underrepresented regions.

- Use as part of a broader policy strategy. Sanctions tend to be a favored tool of the Trump administration, but they cannot be the only tool used. A broader, whole-of-government strategy that includes GloMag sanctions is most likely to achieve the policy objectives. Relying on GloMag sanctions to deliver too much will render the tool more likely to achieve less.

- Do not overuse the tool. GloMag sanctions are not the only tool in the US government’s toolbox to combat human rights abuses and corruption, and it is unlikely to be the most appropriate tool for every scenario.27United States Department of the Treasury, “Glossary” Financial Crimes Enforcement Network. https://www.fincen.gov/sites/default/files/advisory/2018-07-03/PEP%2520Facilitator%2520Advisory_FINAL%2520508%2520updated.pdf The thoughtful, calibrated application of GloMag sanctions will avoid overuse and mitigate against ineffective use. The bar for sanctions targets must continue to be held high with each target thoughtfully chosen to avoid perceived bias toward a specific group.

- Support compliance. Sanctions are only as effective as their implementation and compliance. Increasing efforts to ensure that both US and international companies respect the GloMag sanctions will make the tool that much more effective.

- GloMag sanctions should not be a replacement for a targeted sanctions program. When the situation in a specific country warrants a targeted response, a country–specific sanctions program should be considered. In addition to the GloMag authority, at least a dozen other OFAC sanctions programs include designation criteria for human rights abuse, corruption, or both.28National Archives, “Global Magnitsky Act Human Rights Accountability Act Report” Federal Register, 20 June 2017. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2017/06/20/2017-12791/global-magnitsky-human-rights-accountability-act-report These country-specific authorities are tailored to the situation in the country, both in policy messaging and in additional criteria for designation. The GloMag authority is robust, but its stature will decline if it becomes the replacement for a thoughtful country-specific program.

- Stay responsive. To its credit, following the release of US pastor Andrew Brunsun from detention in Turkey, OFAC delisted the two members of the Turkish cabinet who were sanctioned under GloMag authorities for their role in his detention.29United States Department of the Treasury, “Global Magnitsky Designations Removals” Office of Foreign Assets Control, 2 November 2018. https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/OFAC-Enforcement/Pages/20181102.aspx and United States Department of the Treasury, “Treasury Sanctions Turkish Officials with Leading Roles in Unjust Detention of U.S. Pastor Andrew Brunson” US Treasury, 1 August 2018. https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm453 In order for GloMag sanctions to incentivize behavioral change, timely delistings must continue when appropriate.

Conclusion

The increased attention to the GloMag sanctions authority as a potential tool for responding to the Khashoggi murder is timely. This targeted authority arms the Trump administration with a tool to respond to complex political situations such as this, provided sufficient evidence is available. A useful precedent for using the GloMag authority was set in December 2017 with the designation of Julio Antonio Juarez Ramirez.30United States Department of the Treasury, “United States Sanctions Human Rights Abusers and Corrupt Actors Across the Globe” US Treasury, 21 December 2018. https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm0243 Juarez is a Guatemalan congressman accused of ordering a murderous attack on Prensa Libre correspondent Danilo Efrain Zapan Lopez, a journalist whose reporting had hurt Juarez politically. The Trump administration had the benefit of a reputable third-party commission’s report informing that designation. While the investigation into the facts and circumstances surrounding the Khashoggi murder is ongoing, the use of the GloMag tool to publicly punish a political figure responsible for silencing a critical journalist has already been demonstrated. This dynamic authority should continue to be considered among the policy response options.

While the threat of GloMag sanctions exists in the Khashoggi context and otherwise, international businesses should adjust their risk calculus accordingly. As allies, partners, and NGOs increasingly draw on this authority, the tolerance for serious human rights abuses and corruption will hopefully decline in parallel.

Image: A demonstrator holds picture of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi during a protest in front of Saudi Arabia's consulate in Istanbul, Turkey, October 5, 2018. REUTERS/Osman Orsal