More than six years after Libya’s 2011 revolution against Muammar al-Qaddafi, the situation in the country is significantly more complex and dangerous. The failure of the 2011 NATO intervention to assist the country with a comprehensive stabilization process led to rapid deterioration on the ground and created an opportunity for external actors to pursue competing self-interests in the country. While in most cases the factional rivalries in Libya have real roots, they have been exacerbated by the interests of both regional and international actors, and the resulting proxy conflict in Libya has significantly weakened the UN-led negotiation process.

In this issue brief, Dr. Karim Mezran and Elissa Miller explore the dynamics of regional and international actors most involved in Libya’s proxy conflict, as well as recent incidents of escalation that threaten to further destabilize the country. The authors argue that ultimately, the stabilization of Libya should be the primary goal of any Western engagement. In particular, the failure of the UN-led negotiations and lack of cohesion between European actors necessitates a leadership role for the United States in Libya. The United States is the only country that can credibly employ both carrot—for those seeking to reach a negotiated agreement—and stick—for those aiming to defend entrenched criminal interests or support the establishment of autocratic rule. A targeted Western intervention built on robust diplomacy among Europe and the United States in support of a Libyan-created consensus government could stabilize the country. Given the critical national security implications of Libya’s chaos for the United States and its European allies, such an effort would in the long run be in the best interest of the Libyan people and of those states with an interest in a stable North African region.

Introduction

There is a continuous debate in the public sphere on whether the 2011 NATO intervention in Libya was a success or a failure. Did it constitute the beginning of a new era, or the destruction of a nation state? It is easy to fall into the trap of labeling international interventions as either good or bad. However, interventions are rarely, if ever, that simple. A more nuanced way of judging interventions is to focus on whether they are carried out correctly. In the international arena, interventions can be necessary or even useful, but they must be planned with a clear focus and agreed to by—and if possible developed with—local actors on the ground.

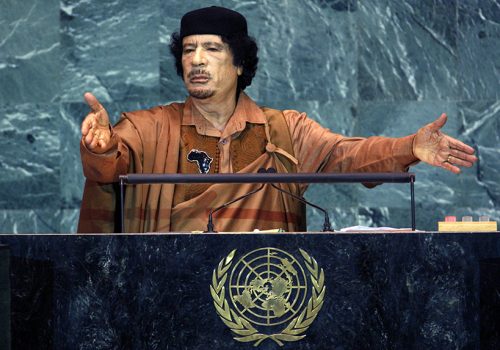

In March 2011, NATO led a military intervention in line with United Nations (UN) Security Council Resolution 1973 that authorized member states to take all necessary measures to protect civilians under threat of attack in Libya.1United Nations Security Council, Resolution 1973, March 17, 2011, http://www.nato.int/

nato_static/assets/pdf/pdf_2011_03/20110927_110311-UNSCR-1973.pdf The mandate was to protect the civilians of Benghazi who had revolted against Muammar al-Qaddafi’s regime. Despite this limited mandate, the way the NATO military operations were carried out made it immediately evident that the real goal of the intervention was much wider, namely to provoke the collapse of Qaddafi’s regime. Coalition forces extensively bombed targets outside of the scope of the mandate with a clear intent to kill Qaddafi, a fact demonstrated by the bombing of a compound of villas near Tripoli where Qaddafi was supposedly hiding that killed his youngest son, Saif al-Arab. However, the coalition failed to set out a plan for the restoration of public order in Libya.

As a result, more than six years later, the situation in Libya is significantly more complex and dangerous. The militias who fought against Qaddafi developed diverging interests and found value in entrenching their control over cities and villages. This led to a fragmentation of authority, which in turn contributed to the proliferation of criminal organizations that further undermined any reconstruction efforts and the possible establishment of a state apparatus. Inevitably, the rivalry among various factions dragged a series of external actors into the politics of Libya, which turned the country’s conflict into a proxy war.

Few voices in recent years have supported the idea of another NATO or UN-led intervention to reset Libya on a path toward stability. These voices went unheeded for many reasons, ranging from lack of appetite in foreign capitals for another military intervention to hypothetical negative Libyan reactions. Many on the ground immediately spoke out against such a possibility, claiming that another intervention would violate Libya’s national sovereignty. The bad faith of most of these actors, who spoke more in defense of their entrenched interests than in the interests of the population, became clear with the passing of time.

The interests and operations of international actors in Libya have become simultaneously complex and pervasive. An understanding of these dynamics makes it apparent that only coordinated action by the West to insulate the country from competing regional interests in Libya’s internal affairs would have the ability to successfully reestablish order. This could include a wellplanned, organized, and limited military intervention in support of Libyan forces that have an interest in resolving the crisis and building a new, more pluralistic state. Over six years later, Western countries are faced with the same choice of intervening or watching the chaos unfold.

Immediate aftermath of the intervention

The biggest shortcoming of the 2011 NATO intervention was the failure to assist the country with a comprehensive stabilization process following the operation. While NATO may not have been able to prevent regional actors from getting involved in Libya—indeed, the country is of important economic and national security interest to its neighbors Egypt, Tunisia, and Algeria and holds significance for the Gulf as well—a continued presence in Libya focused on stabilization could have helped manage post-intervention contention among the various competing parties. Instead, NATO’s departure and determination not to “own” the Libyan issue led to a rapid deterioration on the ground.

The rivalry between domestic factions and their international supporters reached its climax in the summer of 2014 when the country was de facto split into two parts, one in Tobruk in the east under the control of General Khalifa Haftar and the newly elected House of Representatives (HoR), and one in the west led by Islamist-leaning militia leaders and those in the city of Misrata.

While in most cases the factional rivalries in Libya have real roots, they have been exacerbated by the interests of foreign actors. The United Nations and European Union as collective organizations sought to find a negotiated solution to the civil war, which culminated in the signing of the UN-sponsored Libyan Political Agreement (LPA) in Skhirat, Morocco, in December 2015. The LPA formed a Presidency Council (PC) and a cabinet, the Government of National Accord (GNA), led by Prime Minister Fayez al-Serraj.2United Nations Security Council, Document 1016, “United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland: Draft Resolution,”

December 22, 2015, https://unsmil.unmissions.org/sites/default/

files/UNSC_RES_2259_Eng_1.pdf

Despite major efforts at bolstering the PC/GNA, more often than not the United Nations and the European Union were undermined by the double game played by some of their members. While almost all states formally pledged allegiance to the UN-led process, many behaved differently on the ground. The following analysis explores the dynamics of those foreign actors most involved in Libya’s proxy conflict.

Regional actors

Because of personal relations between the Qatari elite, authoritative figures in the Muslim Brotherhood, and Islamist-leaning intellectuals and personalities, Qatar in 2011 openly supported the revolt against Qaddafi and actively operated to strengthen forces close to its Islamist allies. The small Gulf country continues to do so today. There was a short period in 2015 in which, because of US and UN pressure, Qatar suspended support to its proxies in Libya. But it is widely believed that Qatar resumed this support in early 2016. Doha’s interests in Libya are not only economic and political; engagement in Libya is a form of power projection through which Qatar supports the establishment of sympathetic regimes in areas of strategic importance. It is also widely believed that a large part of the support that Qatar provides to its allies is carried out in collaboration with Turkish authorities. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has often spoken with sympathy for the cause of Islamists in Libya.3Barin Kayaoglu, “Why Turkey Is Making a Return to Libya,”

Al-Monitor, June 14, 2016, http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/en/

originals/2016/06/turkey-libya-economic-interests-ankara-tripoli-embassy.html

The United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Saudi Arabia hold a diametrically opposed vision to that of Qatar. In the last decade, both these states have come to see the Muslim Brotherhood and political Islam as a threat to their very existence. As a result, they have launched a determined campaign against political Islam across the region. These efforts peaked in June 2017 when Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt, and Bahrain severed diplomatic ties with Qatar and moved to isolate Doha by cutting land, sea, and air routes to the country, igniting one of the most significant diplomatic rifts in the Gulf in decades.4Jon Gambrell, “Saudi Arabia, Egypt, UAE and Bahrain Cut Ties to

Qatar,” Associated Press, June 5, 2017, http://abcnews.go.com/

International/wireStory/bahrain-cuts-diplomatic-ties-qatar-gulfrift-deepens-47833417 The pro-Haftar government in Tobruk also joined the Saudi bloc in cutting ties with Qatar. Haftar, who was promoted to Field Marshal by the HoR in September 2016, may now believe that the rift in the Gulf Cooperation Council will strengthen his anti-Islamist campaign and garner him more support in his ambition to gain control of the entire country.

Egypt’s national security strategy views the establishment of an Islamist-free zone of order on its western border as a primary objective. This has guided Egypt’s strong and steadfast support for Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA) and its operations against Islamists in Benghazi and more broadly in the country’s eastern province. Thanks to Egyptian and Emirati assistance, Haftar has obtained discrete, albeit bloody, military victories in Benghazi and in the Gulf of Sidra. Egyptian and Gulf military support to Haftar violates the UN arms embargo (implemented under UN Security Council Resolution 1970) and flies in the face of professed Egyptian and Emirati support for the UN-led negotiation process that produced the LPA and PC/GNA.5United Nations Security Council, Resolution 1970, February

26, 2011, http://www.nato.int/nato_static/assets/pdf/pdf_2011_02/20110927_110226-UNSCR-1970.pdf

Cairo’s involvement on the side of Haftar has been particularly problematic, because Egyptian support may have allowed Haftar to believe that he can pursue a military victory on the ground. This has undermined the possibility of a successful negotiated solution. In fact, Haftar, operating under a perceived elevated position, has not shown any warmth towards either the UN negotiation process or the PC/GNA.

Egypt’s interests are clearly not limited to the establishment of a security zone on its borders. No doubt Cairo also recognizes the economic advantages that would come from exercising influence over the eastern part of Libya. Still, it is possible that these interests do not align with Haftar’s ambition to rule over the whole country. Egypt’s economic crisis should push authorities in Cairo to limit involvement with Haftar’s campaign and cash out whatever they can from his control of eastern Libya.6Mohsin Khan and Elissa Miller, The Economic Decline of Egypt

After the 2011 Uprising, Atlantic Council, June 2016, http://www.

atlanticcouncil.org/publications/reports/the-economic-declineof-egypt-after-the-2011-uprising Cairo would prefer to influence part of Libya—the east—and obtain lucrative advantages through reconstruction rather than engage with Haftar in a longer, more expensive, and likely problematic military campaign to conquer all of Libya.

Libya’s two western neighbors, Tunisia and Algeria, are watching warily. Tunisia is too small and powerless to affect any outcome in its larger neighborhood, but it is fearful of the potential spillover of security threats in its southern territory.7Tarek Amara and Patrick Markey, “Border Attack Feeds Tunisia

Fears of Libya Jihadist Spillover,” Reuters, March 14, 2016, http://

www.reuters.com/article/us-tunisia-security-idUSKCN0WF072 Instability in Libya has also severely impacted Tunisia’s already struggling economy.8Elissa Miller, “Why Libya’s Stability Matters to the Region,”

MENASource, Atlantic Council, January 25, 2017, http://www.

atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/why-libya-s-stability-matters-to-the-region. Tunisia has, therefore, exerted every possible diplomatic pressure to support a negotiated solution to the Libyan crisis.

Algeria, meanwhile, has limited its involvement in Libya to diplomacy. Algeria’s fragility, stemming from a succession crisis and a constrained economic environment, restricted its role in Libya. Algeria’s traditional foreign policy, through which it played a balancing role in limiting Moroccan and Egyptian influence over the Maghreb, would have normally compelled the country to contain and counter Cairo’s involvement in Libya’s disorder. The absence of Algerian leadership on this issue is a clear indicator of Algeria’s current internal fragility.

Both Algeria and Tunisia have sought to engage with Cairo on diplomatic efforts to address the conflict in Libya. In June 2017, Libya’s three neighbors met in Algiers where they agreed to push for an inclusive political dialogue and rejected the use of military force.9“Libya’s Neighbors Push Political Deal over Military Solution,” Reuters, June 5, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-libya-security-idUSKBN18X2TC

Other minor regional actors such as Chad and Sudan also play a role in supporting competing factions in Libya through mercenaries. In addition, components of Chadian and Sudanese armed opposition forces have found sanctuary in the ungoverned southern region of Libya. However, Chad and Sudan do not play as significant a role in the proxy conflict in Libya.10Jérôme Tubiana and Claudio Gramizzi, Tubu Trouble: State and

Statelessness in the Chad–Sudan–Libya Triangle, Small Armys

Survey, 2017, http://www.smallarmssurveysudan.org/fileadmin/

docs/working-papers/SAS-CAR-WP43-Chad-Sudan-Libya.pdf

International actors

Haftar, possibly recognizing Egypt’s disinclination to support a military effort to retake the entire country, has pursued support from another powerful actor: Russia. Haftar may also view engagement with Russia as an opportunity to draw the United States to his side by threatening to provide the traditional American rival with an opportunity to establish a foothold in the central Mediterranean.

But this is a dangerous game; Russia is a shrewd actor with clear strategic interests in Libya that are not limited to Moscow’s supposed interest in establishing a military base or engaging in the sale of military equipment. Rather, Russia’s interest lies in projecting power in an area of critical importance to Western interests and thus frustrating the same NATO actors challenging Moscow on its eastern front.

Notably, even as it militarily supports Haftar (or at least claims to), Russia continues to profess support for the UN-led negotiations and the PC/GNA in Tripoli. This suggests that concerns regarding a Russian intervention in Libya comparable to that in Syria have been blown out of proportion. In effect, Moscow is playing both sides by supporting the LNA while also expressing willingness to support Serraj’s government and act as a powerbroker amid absent Western leadership.11“Russia Urges ‘National Dialogue’ at Libya PM Meeting,” Daily

Mail, March 2, 2017, http://www.dailymail.co.uk/wires/afp/article-4276066/Russia-urges-national-dialogue-Libya-PM-meeting.html This gives Russia the opportunity to fill the void of leadership left by the West, especially the United States, in Libya. Russia is unlikely to commit fully to Haftar or attempt to establish a base in Libya any time soon.

The most influential European countries—the United Kingdom, France, and Italy—have also played a role in this proxy war. Italy has remained constant and coherent in its support for Serraj’s PC/GNA while also recognizing the importance of including Haftar in a settlement.12Federica Saini Fasanotti and Karim Mezran, “No, Italy Is Not

Guilty of Neocolonialism in Libya,” Brookings Institution, April

3, 2017, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2017/04/03/no-italy-is-not-guilty-of-neocolonialism-in-libya/ However, the behavior of the United Kingdom and France has been more ambiguous. While both countries have rhetorically supported the LPA and Serraj, their special operations forces have actively assisted Haftar’s troops in their fight against Islamists in Benghazi and in other eastern areas.13John Pearson, “French Support of Rival General Threatens Libya’s UN-Backed Government,” The National, July 23, 2016, http://

www.thenational.ae/world/middle-east/french-support-of-rivalgeneral-threatens-libyas-un-backed-government France has an interest in maintaining influence in the southern part of Libya and therefore has not hesitated to support different factions in the country irrespective of the consequences for the political negotiations process. Europe also appears more concerned with stemming the threat from a worsening migration crisis emanating from Libya’s shores than with the need for Libyan reconciliation.

On the face of it, the United States has no vital interests at stake in Libya’s crisis other than the fight against terrorism, given the limited foothold the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) possesses in Libya following its ejection from the city of Sirte in late 2016. But a slightly deeper analysis demonstrates that, in reality, the United States has significant interests in Libya that should make the country’s stabilization a key focus of US foreign policy. The risk of instability spilling into important US partners such as Egypt and Algeria, as well as the migrant crisis facing allied Southern European countries, are reasons enough for the United States to adopt a larger role in Libya.

Current policy options

Ultimately, the stabilization of Libya should be the primary goal of any Western engagement. The LPA, which produced the PC/GNA, has not taken off, and the weakness of the unity government is a result of the failure of UN leadership. The scandal behind the departure of the former Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General Bernardino León damaged the credibility and effectiveness of the UN Support Mission in Libya.14“Anger at UN Chief Negotiator in Libya’s New Job in

UAE,” Al Jazeera, November 5, 2015, http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2015/11/anger-chief-negotiator-libya-job-uae-151105161323791.html Meanwhile, maneuvering by the United States and Russia prevented for months the appointment of a replacement to former UN Representative Martin Kobler, further weakening the United Nation’s role.15Mr. Ghassan Salamé of Lebanon – Special Representative and

Head of the UN Support Mission in Libya,” United Nations, June

22, 2017. https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/personnel-appointments/2017-06-22/mr-ghassan-salam%C3%A9-lebanon-special-representative-and There is by now a majority consensus that the LPA must be amended.

The failure of the UN-led negotiations and lack of cohesion between European actors necessitate a leadership role for the United States in Libya. The United States is the only country that can credibly employ both carrot—for those seeking to reach a negotiated agreement—and stick—for those aiming to defend entrenched criminal interests or support the establishment of autocratic rule. The competing and conflicting interests of key international actors was the main reason behind the failure, thus far, of the LPA project. It is imperative that the United States exercises decisive leverage to persuade the international actors involved in the conflict to relinquish support for armed factions on the ground and use their influence instead to convince all parties to come to an agreement.

In doing so, it is critical that President Donald Trump’s administration understands that the situation on the ground in Libya is such that an attempt by any party in the conflict to militarily conquer the country is neither a possible nor welcome solution. The belief that a shift in US support towards Haftar could be a solution for Libya is misplaced and the product of misinformation spread by various local actors with the precise purpose of enticing the United States to abandon Serraj in favor of his eastern rival. The same objection can be applied to those who suggest partitioning Libya as the best way out of the current crisis. The fragmentation of each region, the internal divisions, and the lack of high-level leadership, to say nothing of how partition would allocate Libya’s natural resources, make any idea of partition simply a trigger for further violence.16Geoff D. Porter, “So You Want to Partition Libya,” Politico, April

11, 2017, http://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2017/04/libya-partition-sebastian-gorka-215012

However, the Trump administration appears unlikely to take up such a leadership role. In April, during a joint news conference during Italian Prime Minister Paolo Gentiloni’s visit to the White House, President Trump said he does “not see a role [for the United States] in Libya” beyond fighting ISIS.17Steve Holland and Eric Walsh, “Trump Says Only Role for US

in Libya Is Defeating the Islamic State,” Reuters, April 20, 2017,

http://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-trump-libya-idUSKBN17M2OC “We are effectively ridding the world of ISIS. I see that as a primary role, and that’s what we’re going to do, whether it’s in Iraq or in Libya or anywhere else. And that role will come to an end at a certain point,” Trump added. This indicates that the administration views Libya primarily through the lens of countering ISIS and other extremist Islamist groups.

Yet the United States clearly has significant interests at stake in a stable and secure Libya and should consider assuming a larger role in Libya than the one articulated by President Trump. Several US officials would agree.

In March 2017, before the Senate Armed Services Committee, the US Africa Command head Gen. Thomas D. Waldhauser said, “the instability in Libya and North Africa may be the most significant near-term threat to US and allies’ interests on the continent.”18Eric Schmitt, “Warning of a ‘Power Keg’ in Libya as ISIS Regroups,” New York Times, March 21, 2017, https://www.nytimes.

com/2017/03/21/world/africa/libya-isis.html?_r=0

A month later, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee convened a hearing on US policy options in Libya, during which Ranking Member Senator Ben Cardin (D-MD) said it is in the national security interest of the United States to engage with Libya.19“The Crisis in Libya: Next Steps and US Policy Options,” United

States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, April 25, 2017,

https://www.foreign.senate.gov/hearings/crisis-in-libya-nextsteps-and-us-policy-options-042517 “We do have a role in Libya,” he said in response to Trump’s statements.

Moreover, there is no evidence that Washington is prepared to shift its support from the PC/GNA to Haftar. Indeed, in an April meeting of the G7 foreign ministers, US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson signed onto a declaration expressing support for the PC/ GNA and calling on the elimination of spoilers from the negotiation process. The US ambassador to Libya, Peter Bodde, again reaffirmed US commitment to the UN-led process during a visit with Serraj in Tripoli in May.20Aidan Lewis, “US Envoy Endorses Libya’s UN-Backed Government in Whirlwind Visit to Tripoli,” Reuters, May 23, 2017, http://

www.reuters.com/article/us-libya-security-usa-idUSKBN18J2HR

Those within the US government—in both the executive and legislative branches—who recognize the importance of reaching a peaceful settlement in Libya should therefore push the administration to put its weight behind an inclusive negotiation process. In the meantime, key European stakeholders, led by Italy, should continue to elevate Libya as a priority for the international community. If Rome can marshal a united front among leading European actors in support of an inclusive peace process in both word and deed— one that penalizes spoilers and pressures international actors to cease support for competing proxies—it could, with support from US congressional leaders, convince the Trump administration to invest leadership in finding a solution for Libya’s conflict.21Karim Mezran and Elissa Miller, “Trump on Libya: What Now?”

MENASource, Atlantic Council, April 21, 2017, http://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/trump-on-libya-what-now

Italy is already playing an important role in bringing opposing sides of Libya’s conflict together in the absence of stronger leadership from the United States and the United Nations. In April, Rome brokered a diplomatic agreement between Agileh Saleh, the president of the State Council—the advisory body overseeing the GNA—and Abdulrahman Swehli, the president of the HoR. “We agreed to reach peaceful and fair solutions to outstanding issues,” a statement from the State Council said following the meeting.22Patrick Wintour, “Libya’s Warring Sides Reach Diplomatic Breakthrough in Rome,” The Guardian, April 24, 2017, https://www.

theguardian.com/world/2017/apr/24/libya-warring-sides-diplomatic-breakthrough-rome

Weeks earlier, a peace deal was reached in Rome after months of direct and indirect talks between the Tebu, Tuareg, and Awlad Suleiman tribes, in which the southern tribes agreed to cooperate on development in South Libya and address the issue of illegal migration.23“Tebu, Tuareg, and Awlad Suleiman Make Peace in Rome,” Libya

Herald, March 30, 2017, https://www.libyaherald.com/2017/03/30/

tebu-tuareg-and-awlad-suleiman-make-peace-in-rome/

Given these successful first steps towards a peaceful solution, Italy should take the lead in reorganizing the Libyan component of the political dialogue in a more inclusive direction that ensures modifications to the LPA are undertaken with as much consensus as possible. The leadership of the major armed groups in the country should be engaged and involved in the negotiations. Tribal and economic heavyweights should also be included; their presence would ensure enough stakes in the success of the negotiation process and its outcome. Rome should also continue to call on Washington—and the wider international community—to view Libya and overall security in the southern Mediterranean as a top priority for global security.24H.E. Angelino Alfano and Frederick Kempe, “Facing Common

Challenges: The Italian Contribution to Security,” Atlantic Council

Webcasts, March 21, 2017, http://www.atlanticcouncil.org/events/

webcasts/facing-common-challenges-the-italian-contribution-to-security

Spoilers add escalation

The fragmentation of European actors in Libya, combined with the lack of interest expressed by the US administration in trying to stabilize the country, has left a void that Haftar’s main supporters, the UAE and Egypt, have attempted to fill. In early May, through an initiative driven by Abu Dhabi and Cairo, the UAE staged a meeting between Haftar and Serraj. This was the first meeting between the two rival leaders since early 2016 following the signing of the LPA.25“Fayez al-Sarraj Meets Khalifa Haftar in UAE for Talks,” Al Jazeera, May 2, 2017, http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/05/

fayez-al-sarraj-meets-khalifa-haftar-uae-talks-170502140623464.

html

While no official statements regarding the results of the meeting were released by either party, information was leaked that an agreement had been reached between Serraj and Haftar. The main points of the supposed agreement included reducing the PC from nine to three members—comprised of Haftar, Serraj, and the HoR’s Agileh Saleh—holding elections in 2018, and canceling Article 8 of the LPA. This article has been a major point of contention for Haftar, as it would in theory allow the PC to control the army, a role that Haftar wants for himself.

Yet rather than a breakthrough, the meeting was, in effect, an attempt by Haftar to impose a conditional surrender by Serraj. By bringing Serraj and Haftar together and leaking the details of the “agreement,” Abu Dhabi and Cairo controlled the optics of the meeting and presented it as a demonstration of Haftar taking steps to moderate. Yet Haftar’s interest in elections and in joining the PC are likely hollow; rather, he is attempting to garner further power in Libya through whatever possible and advantageous avenue. The result is a de facto undermining of attempts by Rome and other Western countries to marshal a real, inclusive consensus.

The meeting in Abu Dhabi also illustrated the increasing weakness of Serraj and the PC/GNA. Serraj’s participation in the UAE-Egypt initiative upset several unity government allies opposed to any role for Haftar in a future settlement. Thus, forces from Misrata on May 17 attacked Haftar’s LNA at the Brak al-Shati military base in the south. Close to 150 members of the LNA were reported dead, and Misrata’s Third Force, as well as the Benghazi Defense Brigades, were accused of summarily executing Haftar’s men.26“Libya: 141 People Killed in Brak al-Shat Airbase Attack,” Al Jazeera, May 20, 2017, http://www.aljazeera.com/

news/2017/05/libya-141-people-killed-brak-al-shat-airbase-attack-170520082052419.htmlThis dangerous escalation provides Haftar with reason enough to refuse to engage further with the PC/GNA and expand his military campaign towards Misrata and Sirte through reprisal attacks.

Ultimately, the UAE-Egypt effort set the stage for further fragmentation and division among Libyan actors, which threatens to condemn Libya to a state of permanent civil war. Egypt’s airstrikes weeks later in Derna, in coordination with the LNA, following an attack on Egyptian Christians in Minya, further demonstrate Cairo’s willingness to coordinate with Haftar’s forces on perceived national security threats.27Ahmed Aboulenein, “Egypt to Press Ahead with Air Strike after

Christians Attacked,” Reuters, May 29, 2017, http://www.reuters.

com/article/us-libya-security-idUSKBN18P0GP This coordination could further boost Haftar’s position and inflame tensions within Libya.

A better intervention?

Given heightened escalations and stalled diplomatic progress, military intervention may be needed at some point to ensure the security of Libya’s Western-backed government and the country’s main infrastructure. There is no doubt that whatever form this intervention would take, it would need to be much different in both breadth and scope from the 2011 intervention. That Serraj has called for an international intervention to support his government and reestablish security, coupled with the population’s exhaustion and aggravation with pervasive insecurity and an economy crisis, constitutes an important opening.28“HoR Condemns Serraj’s Foreign Intervention Call,” Libya Herald,

April 16, 2017, https://www.libyaherald.com/2017/04/16/hor-condemns-serrajs-foreign-intervention-call/

The West, led by Europe, should consider dispatching several thousand soldiers as a stabilizing force to guarantee security and key infrastructure in the capital of Tripoli. These forces would collaborate with militias that are willing to 1) support a new government produced by a revised LPA and 2) ultimately be incorporated into a professional, nascent Libyan armed force. These foreign troops could also engage in training the presidential guard and other security forces on the ground. Those armed groups interested in pursuing grievances and retaliatory attacks against Haftar’s LNA must be convinced to support the government under a revised agreement and accept that Haftar will likely need to play a role in any future settlement. This may require a national reconciliation process, of which Libya is in sore need but has not yet been established.

Notably, the United States could be considering expanding diplomatic and military involvement in Libya to bolster America’s counterterror effort by also contributing to reconciliation among the country’s major factions. It is critical that such an effort focus not only on counterterror goals but also on stabilizing the country in concert with key European partners. A major component of this effort should be aimed at eradicating the web of criminal networks that prevents the establishment of law and order in Libya and benefits terror groups.29Barbara Starr, “US military considers ramping up Libya presence,”

CNN, July 10, 2017. http://www.cnn.com/2017/07/10/politics/

trump-us-military-libya-strategy/index.html

A potential risk to this effort could be a rejection by Haftar of the international intervention as a foreign invasion and the mobilization of his troops and allies against the Western forces. However, opposition by Haftar would be useless and rather counterproductive if the international community can help secure Tripoli quickly and bring order and cohesion to the militias in the capital. In such a scenario, theoretically, it would be more convenient and advantageous for Haftar to join and guarantee a role for himself within the nascent government rather than blindly oppose a strengthened Tripoli and plunge the country into full-fledged war. These efforts should be undertaken within a theoretical framework for a decentralization process that shifts functions and duties of the state from the center to the periphery.30Karim Mezran, Elissa Miller, and Emelie Chace-Donahue. “The

Potential for Decentralization in Libya,” MENASource, Atlantic

Council, June 26, 2017. http://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/the-prospect-of-decentralization-in-libya The stabilization of the whole of Libya should start from the local level and move from the bottom up.

The establishment of a minimum level of security in the city of Tripoli, which by itself comprises almost a third of the population of Libya, could allow the PC/ GNA to initiate a series of economic projects—such as restoring roads, repairing the power grid and electrical infrastructure, and rebuilding schools and hospitals that have been badly damaged by war and neglect— to repair Tripoli’s infrastructure and restart economic activity in the city. Success in these endeavors could slowly and progressively, but consistently, be expanded throughout the country. Success in Tripoli could be replicated in every city and village in Libya, where local militias would join municipal security forces under the supervision of the central government and the support of the reconstituted national armed forces.

The international community could further support economic revitalization by establishing an international financial committee that would support government reforms and development projects through an advisory role. This committee could also push for more transparency and accountability in the operations of Libya’s main economic and financial institutions, such as the Central Bank of Libya, the Libyan Investment Authority, and the National Oil Corporation.

All of this would also help private corporations and international investors identify areas for development in the country and, in cooperation with Libyan actors, create a positive cycle that would build Libyan capacity and construct an active economy. The success of this plan means setting a deterrent against Haftar’s and others’ ambitions to weaken the PC/GNA and pursue a military victory. It also entails rebuilding support among western militias, including those from Misrata, for the PC/GNA. To avoid escalation, these militias would need to be convinced that a negotiated settlement, even one that would bring Haftar into the fold, would not threaten their interests. Progress in this direction was made in mid-May 2017, when pro-GNA forces defeated and pushed militias loyal to the more pro-Islamist competing rump government of Khalifa Ghwell out of Tripoli, thus strengthening the PC/GNA’s hold on Tripoli and its ability to actively solidify its rule.

If a targeted Western intervention, built on robust diplomacy among Europe and, ideally, the United States, in support of a Libyan-created consensus government, succeeds in Tripoli and establishes a credible model, Haftar and other spoilers would have no choice but to join that effort and participate in the reconstruction of the country and of its institutions. Military intervention—a European enterprise enjoying American support—would be a last resort.

Conclusion

The West today faces a difficult choice in Libya. The disorder that enveloped the country following the 2011 NATO intervention makes any consideration of productive engagement in the country now an unattractive concept. However, it is possible to conceive of a well-planned targeted effort that could stabilize the country.

In the absence of Western leadership, Russia and regional actors with their own interests have demonstrated their willingness to step into the fray and manipulate developments on the ground. If the United States and its European allies continue to let Haftar’s allies fill the void, Libya’s conflict will only continue to escalate.

A clear plan to help stabilize Libya would involve targeted assistance from the West to bolster the PC/ GNA’s control over Tripoli and convince the various actors to engage in an inclusive, cohesive negotiation process. Given the critical national security implications of Libya’s chaos for the United States and its European allies, the choice to step back may encourage further escalation that would ultimately drag the West into Libya. A well-planned stabilization effort now, rather than an unwelcome and compulsory intervention later, would in the long run be in the best interest of the Libyan people and of those states with an interest in the stability of the region.