Reprogramming the future: The specialized semiconductors reshaping the global supply chain

Introduction

In 2014, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) launched a massive investment campaign to develop its domestic semiconductor industry. While significant policy and media attention is focused on PRC efforts to catch up to the United States at the leading edge of semiconductor manufacturing, PRC investments in foundational, or “lagging-edge,” semiconductors are also an important strategic development. In this issue brief, the authors examine PRC investments in field-programmable gate arrays (FPGAs) as an example of critical, specialized semiconductors that are often manufactured with foundational technology.

FPGAs are specialized semiconductor chips that offer a unique combination of flexibility and performance. They are critical components in guided missile systems like the FGM-148 Javelin, automobiles like the Mustang Mach-E electric SUV, telecommunications systems, and cloud data centers. Today, the United States leads the FPGA industry. US firms hold market-leading positions in FPGA design and design software, while most FPGA manufacturing and assembly, testing, and packaging is conducted by US firms or by close allies such as Taiwan.

However, the PRC has steadily increased its semiconductor investment efforts in recent years to develop manufacturing capabilities for foundational semiconductors overall, and design capabilities for FPGAs in particular. This new PRC capacity will come online in one to three years and, given its substantial scale, it may price US FPGA firms out of the critical segments of the FPGA market. This will create both availability and security risks for the US FPGA supply chain.

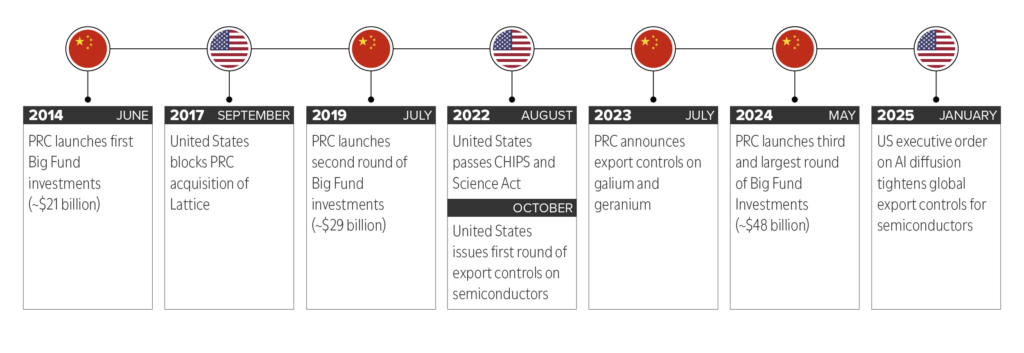

Semiconductors are at the heart of US-China tech tensions

In the last decade, US and PRC policy postures toward the semiconductor industry have changed. As the overall US-China relationship shifted from collaboration to competition,1Graham T. Allison, Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap? (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017); Jake Sullivan, “The Sources of American Power,” Foreign Affairs, October 24, 2023; Odd Arne Westad, “The Sources of Chinese Conduct,” Foreign Affairs, August 12, 2019, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2019-08-12/sources-chinese-conduct. the US-China semiconductor ecosystem has evolved from a benign mutualistic partnership into a strategic competition. This shift, coupled with rising tensions between the United States and the PRC overall, triggered a broad US response, including prohibiting PRC investments, imposing export controls on critical chips and manufacturing equipment, and an industrial policy that supports domestic chipmakers. Key PRC and US actions are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. What steps have the United States and China taken in the race for semiconductor supremacy?

China’s chip strategy is powered by state funding and localized supply chains

In 2014, after the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)2The PRC’s 13th Five Year Plan for the Development of Strategic Emerging Industries tasked the following stakeholders to be responsible for the implementation of PRC’s semiconductor initiatives: The National Development and Reform Commission, Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, Ministry of Science and Technology, Ministry of Finance, Cyberspace Administration of China, and General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine. articulated its ambitions to become a leader across the semiconductor value chain by 2030,3Karen M Sutter, Emily G Blevins, and Alice B Grossman, “Semiconductors and the CHIPS Act: The Global Context,” CRS Report No. R47558 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, updated September 28, 2023, 18, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R47558. it quickly established a National Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund (NICIIF, commonly known as the “Big Fund”) to provide financial support toward those goals. The first phase of funding, amounting to an estimated $21 billion,4Sarah Ravi, “Taking Stock of China’s Semiconductor Industry,” Semiconductor Industry Association, July 13, 2021, https://www.semiconductors.org/taking-stock-of-chinas-semiconductor-industry/. supported domestic semiconductor manufacturing and chip design capabilities, largely through overseas acquisitions and foreign semiconductor equipment purchases.5Sutter, Blevins, and Grossman, “Semiconductors and the CHIPS Act: The Global Context,” 18; Economist Intelligence Unit, “China Boosts State-Led Chip Investment,” Economist Intelligence Unit, March 13, 2024, https://www.eiu.com/n/china-boosts-state-led-chip-investment/.

In 2018, China revised its goal to focus on increasing domestic semiconductor production as part of its Made in China 2025 industrial strategy.6Sutter, Blevins, and Grossman, “Semiconductors and the CHIPS Act: The Global Context,” 18. In the same year, a series of articles appeared in a publication affiliated with the PRC Ministry of Science and Technology. They identified specific “chokepoint technologies,”7Ben Murphy, “Chokepoints: China’s Self-Identified Strategic Technology Import Dependencies,” Issue Brief (Washington, DC: Center for Security and Emerging Technology, May 2022), https://cset.georgetown.edu/publication/chokepoints/. including both semiconductors and the photolithography machines needed to manufacture them.8Murphy, “Chokepoints.”

The second phase of Big Fund investments took place in October 2019, providing an estimated $28.9 billion,9All investment amounts are expressed in US dollars.Sutter, Blevins, and Grossman, “Semiconductors and the CHIPS Act: The Global Context,” 18. to support upstream development and downstream acquisition of semiconductor manufacturing equipment, along with critical raw materials.10Economist Intelligence Unit, “China Boosts State-Led Chip Investment;” Arrian Ebrahimi and Lily Ottinger, “China’s SME Industrial Policy in 5 Charts,” ChinaTalk (blog), May 7, 2025, https://www.chinatalk.media/p/chinas-sme-industrial-policy-in-5. In 2021, the PRC began to supplement Big Fund investments with an explicit dual circulation and indigenous innovation strategy,11Dual circulation is an economic strategy that aims to reduce China’s external economic and technological dependence by emphasizing domestic market growth and maintaining selective global economic engagement. Indigenous innovation refers to Chinese-led technology research and development. aiming to replace US- and foreign-made semiconductors with domestic alternatives.12Semiconductor Industry Association, “SIA Comments to USTR Regarding the 2024-China WTO Compliance Report” (Semiconductor Industry Association, September 10, 2024), https://www.semiconductors.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/SIA-Comments-to-USTR-Regarding-the-2024-China-WTO-Compliance-Report.pdf.

Chinese companies, including those with long-term US ties, are increasingly supporting the PRC government’s initiatives to develop a localized semiconductor supply chain.13Sutter, Blevins, and Grossman, “Semiconductors and the CHIPS Act: The Global Context,” 26. Between 2018 and 2023, the PRC produced 34 percent of the world’s chip design and fabrication-related research articles while the United States trailed behind at 15 percent.14ETO Research Almanac, “Chip Design and Fabrication,” updated January 6, 2025, https://almanac.eto.tech/topics/chip-design-fabrication/. Nine out of the world’s top ten chip research producers are also PRC institutions.15ETO Research Almanac, “Chip Design and Fabrication.” Of course, these statistics should be read with some skepticism, as China has often produced large volumes of lower-quality research publications.16Eleanor Olcott, Alan Smith, and Clive Cookson, “China’s Fake Science Industry: How ‘Paper Mills’ Threaten Progress,” Financial Times, March 28, 2023, sec. The Big Read, https://www.ft.com/content/32440f74-7804-4637-a662-6cdc8f3fba86. However, the sheer quantity of chip-related publications produced by Chinese researchers indicates the PRC’s substantial resource allocation and strategic commitment to advancing its broader semiconductor industry.

In 2024, China announced the third phase of the Big Fund, an estimated $47.5 billion investment focused on chip-making equipment.17Economist Intelligence Unit, “China Boosts State-Led Chip Investment.” However, total PRC semiconductor investment fell sharply in 2024, with analysts attributing the decline to reduced demand and lower government subsidies.18Feng Ning, “China’s semiconductor investment has fallen,” eefocus, March 7, 2025, https://scout.eto.tech/?id=4251.

While the PRC is building capabilities to design and manufacture leading-edge semiconductors, it is also strengthening its capacity to produce lagging-edge semiconductors.19The Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party, “Gallagher, Krishnamoorthi Call for Urgent Action to Reduce US Dependence on PRC Foundational Chips [press release],”,January 8, 2024, http://selectcommitteeontheccp.house.gov/media/press-releases/gallagher-krishnamoorthi-call-urgent-action-reduce-us-dependence-prc. Jeremy Mark, a senior fellow with the GeoEconomics Center of the Atlantic Council, observed that “China has an insatiable appetite for all types of semiconductors and investments have been, by necessity, in legacy chips.”20Jeremy Mark, interview with the authors, February 2025. As part of the PRC’s efforts, PRC FPGA firms are growing. This upward trend demands increased concern even though China’s current FPGA sector is relatively nascent compared to the United States.21Zhiyan Zixun, “FPGA,” Zhiyan Zixun, February 28, 2024, https://www.chyxx.com/wiki/1175487.html.

From Obama to Trump—the US response to PRC investments

The US government has countered China’s semiconductor advancements through intensified foreign investment reviews and export controls, while also tightening US outbound investments into China’s semiconductor sector. The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) has blocked PRC state investments and acquisitions of semiconductor firms consistently across recent presidential administrations. For instance, in 2016, the Obama administration prohibited the sale of the US operations of Aixtron GE, a semiconductor manufacturing equipment firm headquartered in Germany, to a PRC investment firm.22James K Jackson, “The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS),” CRS Report PL33388 (Washington, DC: Congressional Reseearch Service, February 26, 2020, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/RL33388. The following year, the Trump administration blocked the PRC acquisition of the Lattice Semiconductor Corporation, a US FPGA firm, on similar national security grounds.23Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), “Statement On The President’s Decision Regarding Lattice Semiconductor Corporation,” US Department of the Treasury, September 13, 2017, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm0157.

Since 2020, US policy to counter PRC semiconductor industry growth has largely relied on the assumption that the United States and its allies control technological chokepoints, and can deny the PRC access to them using export controls.24Carrick Flynn and Saif M. Khan, “Multilateral Controls on Hardware Chokepoints,” Policy Brief (Washington, DC: Center for Security and Emerging Technology, September 2020), https://cset.georgetown.edu/publication/multilateral-controls-on-hardware-chokepoints/; Ansgar Baums, “The ‘Chokepoint’ Fallacy of Tech Export Controls,” Stimson Center (blog), February 6, 2024, https://www.stimson.org/2024/the-chokepoint-fallacy-of-tech-export-controls/. This approach is largely in-line with the “chokepoint effect” model of weaponized interdependence, as proposed by Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman.25Henry Farrell and Abraham L. Newman, “Weaponized Interdependence: How Global Economic Networks Shape State Coercion,” International Security 44, no. 1 (2019): 42–79, https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00351. Recent policy discussion has begun to question whether efforts to deny access to chokepoints in fact incentivize indigenous PRC technological development, a concern raised in Farrell and Newman’s original paper.26Baums, “The ‘Chokepoint’ Fallacy;” Ansgar Baums and Nicholas Butts, Tech Cold War: The Geopolitics of Technology, Studies in Technology and Security: Innovation, Impact, and Governance (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, Inc., 2025); Semiconductor researcher, January 6, 2025; Farrell and Newman, “Weaponized Interdependence;” Henry Farrell and Bruce Schneier, “Common-Knowledge Attacks on Democracy,” SSRN Scholarly Paper (Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network, October 1, 2018), https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3273111. Similar US efforts to take advantage of chokepoints in the global financial system have spurred both the PRC and US allies in Europe to develop technological solutions to reduce the importance of US-controlled chokepoints.27Martin Sandbu, “The Battle for the Global Payments System Is under Way,” Financial Times, April 6, 2025, sec. Digital currencies, https://www.ft.com/content/40f6e292-839c-4d1f-994e-59bed627b909. Additionally, the US has also increasingly relied on executive directives to limit Chinese access to American capital, beginning with Executive Order 13959 issued by President Donald Trump in 2020, which prohibited US investments in designated Communist Chinese Military Companies (CCMCs). In 2021, President Joe Biden amended EO 13959 and revoked EO 13974 by issuing EO 14032, which expanded the scope to include companies supporting the Chinese Military-Industrial Complex (CMIC) and surveillance efforts while also narrowing investment restrictions by prohibiting indirect investments in CMIC-linked companies. In 2023, Biden signed Executive Order 14105, authorizing the Treasury Department to restrict or require disclosure of US investments in sensitive technologies—such as semiconductors—in countries of concern, particularly China.

As shown in Figure 1, US actions against the PRC semiconductor industry began to increase during the Trump administration in 2018 and carried over to the Biden administration. In response to US restrictions, the PRC enacted similar controls to impose pressure on US firms and its semiconductor industry.

China’s growing involvement in the FPGA industry

The FPGA market has become a key competitive arena between the United States and the PRC. While the United States is still the global leader in FPGAs, China’s substantial investments in the FPGA space present an emerging challenge to the United States’ ability to produce the most advanced FPGA chips and potentially the ability of the United States and its allies to manufacture FPGAs at scale. Our research indicates that the PRC is launching a major buildup of manufacturing capacity at lagging-edge logic nodes, including substantial state investments in FPGA firms.

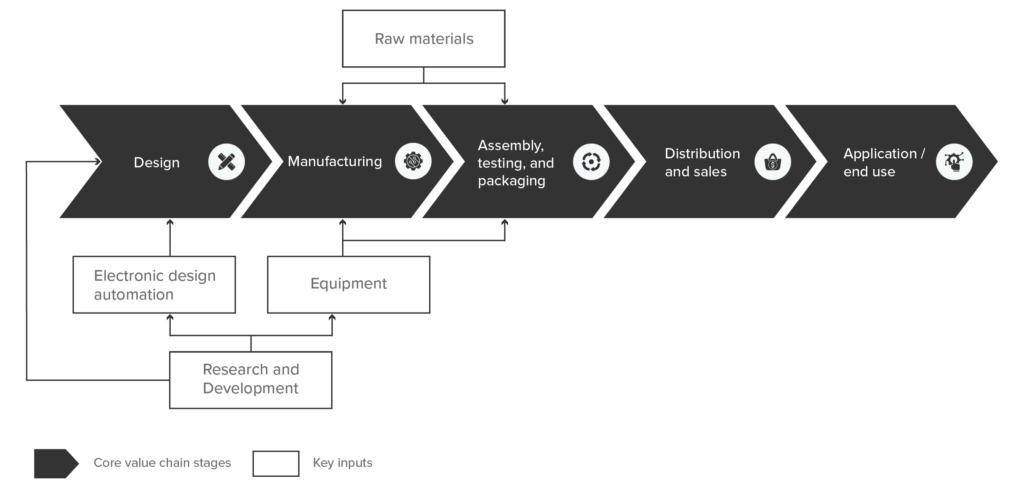

To analyze the FPGA industry and China’s growing involvement, we employ the value chain model described in Figure 2, which includes both core stages of the semiconductor value chain and key inputs.28Michael E. Porter, Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance (New York : London: Free Press ; Collier Macmillan, 1985); Institute for Manufacturing, “Porter’s Value Chain,” University of Cambridge (blog), accessed January 21, 2025, https://www.ifm.eng.cam.ac.uk/research/dstools/value-chain-/; Antonio Varas et al., “Strengthening the Global Semiconductor Supply Chain in an Uncertain Era” (Semiconductor Industry Association and Boston Consulting Group, April 1, 2021), https://www.semiconductors.org/strengthening-the-global-semiconductor-supply-chain-in-an-uncertain-era/; Emerging Technology Observatory, “Advanced Semiconductor Supply Chain Dataset (2022 Release),” 2022, https://eto.tech/dataset-docs/chipexplorer.

Figure 2. An overview of the semiconductor value chain, from initial design through end use

The participants in the FPGA supply chain are grouped into four main categories.

China is increasing its efforts to localize FPGA production in response to growing domestic demands, aiming to decrease reliance on US suppliers, particularly for low- and mid-range FPGAs.29Grand View Research, “China Field Programmable Gate Array (FPGA) Market Size & Outlook,” n.d., https://www.grandviewresearch.com/horizon/outlook/field-programmable-gate-array-fpga-market/china. [1] Specialist in Asian politics and economics, interview, February 21, 2025. US sanctions and export controls have limited China’s access to advanced semiconductor manufacturing equipment, prompting China to increase investments in lagging-edge semiconductor capacity that depends on older, less-sophisticated semiconductor manufacturing equipment (SME).30Specialist in Asian politics and economics, interview, February 21, 2025. The PRC currently holds an advantage in certain aspects of manufacturing and the majority of assembly, testing, and packaging (ATP), while also making significant investments in domestic FPGA firms, specifically in R&D to strengthen its FPGA chipmakers’ design capabilities.

US manufacturers pay the price for China’s chokehold on critical raw materials

China is the leading supplier of raw materials needed for FPGA manufacturing, specifically silicon and gallium. In 2024, the PRC produced approximately 80 percent of global silicon production and 99 percent of worldwide low-purity gallium production.31US Department of the Interior and US Geological Survey, Mineral Commodity Summaries 2025, last updated March 2025, Ibid., 75, 161, https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2025/mcs2025.pdf. Given China’s history of using its critical mineral supply as a geopolitical tool, mounting competition between the United States and the PRC increases the likelihood of PRC restrictions on critical minerals.32Seaver Wang, Peter Cook, and Lauren Teixeira, “How Should We Interpret Chinese Critical Mineral Export Restrictions?,” The Breakthrough Institute (blog), accessed January 22, 2025, https://thebreakthrough.org/issues/energy/how-should-we-interpret-chinese-critical-mineral-export-restrictions. The PRC’s actions to control raw materials to-date—including China’s complete ban on gallium exports to the United States in December 2024 and stricter licensing requirements for other critical minerals in April 2025—have significantly increased prices for various raw materials, including gallium. Even before China’s April 2025 measures, gallium prices had already risen by roughly 80 percent by December 2024,33Gracelin Baskaran and Meredith Schwartz, “China Imposes its Most Stringent Critical Minerals Export Restrictions Yet Amidst Escalating US-China Tech War,” Critical Questions (CSIS blog), December 4, 2024, https://www.csis.org/analysis/china-imposes-its-most-stringent-critical-minerals-export-restrictions-yet-amidst; Archie Hunter and Mark Burton, “What Are Gallium and Germanium? The Niche Metals Hit by China’s Export Ban,” Bloomberg, December 3, 2024, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-12-03/china-gallium-and-germanium-us-export-ban-why-metals-are-key-in-trade-war. thereby increasing the cost of US FPGA manufacturing.

While other countries could step in over time to provide additional gallium capacity, prices may remain elevated or increase further before US and allied gallium production can increase. However, gallium is only one of many critical inputs used in FPGA manufacturing, and many FPGA end customers are largely price-inelastic (e.g., military and defense applications).34Atlantic Council’s Cyber Statecraft Initiative, private roundtable on the security of the supply chain for specialized semiconductors, February 6, 2025, Zoom. This implies that gallium pricing dynamics alone are unlikely to drive major shifts in the FPGA market. China’s dominance and strategic manipulation of its raw material supply reduce the cost of domestic Chinese FPGA manufacturing while driving up manufacturing cost for US FPGAs.

Ensuring continued dominance in assembly, testing, packaging

ATP involves separating silicon wafers into individual chips, which are then connected with other components and packaged into an end product.35Alison Li, “6 Crucial Steps in Semiconductor Manufacturing,” ASML, October 4, 2023, https://www.asml.com/en/news/stories/2021/semiconductor-manufacturing-process-steps. ATP services are typically outsourced to third-party semiconductor assembly and testing (OSAT) firms. While China and Taiwan make up 60 percent of global ATP operations,36Raj Varadarajan et al., “Emerging Resilience in the Semiconductor Supply Chain” (Semiconductor Industry Association and Boston Consulting Group, May 2024), https://www.semiconductors.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Report_Emerging-Resilience-in-the-Semiconductor-Supply-Chain.pdf. China is home to five of the largest OSAT firms globally (JCET, HT-Tch, TF, LCSP, and Chippacking) and is investing in its next-generation advanced packaging capabilities.37Stephen Ezell, “How Innovative is China in Semiconductors?,” Information Technology & Innovation Foundation, Hamilton Center on Industrial Strategy, August 2024, https://itif.org/publications/2024/08/19/how-innovative-is-china-in-semiconductors/; Sujai Shivakumar and Chris Borges, “Advanced Packaging and the Future of Moore’s Law,” Critical Questions (CSIS blog), June 26, 2023, https://www.csis.org/analysis/advanced-packaging-and-future-moores-law. As the semiconductor industry—including FPGA firms—increasingly relies on advanced packaging to drive performance gains,38Shivakumar and Borges, “Advanced Packaging.” China’s advancements in next-generation packaging techniques may increasingly position the country as a significant competitor in the FPGA space and in critical end-customer applications that depend on them, such as artificial intelligence (AI) and data centers.

Big Fund investment fuels the rise of PRC FPGA firms

Investments from the Big Fund in PRC FPGA firms like Anlogic provide early indicators that FPGAs are a focus area for the PRC.39Wu XinZhu, “Where are the investment opportunities in the semiconductor industry chain?,” Sina Finance, June 11, 2024, https://finance.sina.com.cn/wm/2024-06-11/doc-inaykeac8310123.shtml. According to the Atlantic Council’s Jeremy Mark, there is “no evidence that there is a slacking of [Chinese] investments and commitment of resources toward semiconductors and SMEs [as] its technology growth strategy, particularly in AI, requires semiconductors.”40Jeremy Mark, interview with the authors, February 2025. This manufacturing capacity will provide firms with an option to manufacture FPGA chips at costs substantially lower than what is typical today. However, this new manufacturing capacity will likely come with substantial availability and security risks.

There are five notable PRC FPGA firms in the low-to-mid-range FPGA segment:

- Anlogic41Also known as Anlu Information Technology. (安路科技): Anlogic is the largest domestic FPGA vendor in China, although it trails three US firms in Chinese market share.42Greg Gao, “Chinese FPGA Star Anlogic Infotech Gets Listed on Shanghai’s STAR Market,” Ijiwei, n.d., https://jw.ijiwei.com/n/799090. Anlogic held 38.2 percent of the domestic low-end FPGA market share as of 201943Gao, “Chinese FPGA Star.” and mainly targets industrial and automotive applications. Anlogic has received significant support from the PRC government in 2019 through the Big Fund.44Shanghai Anlogic Infotech Co., Ltd., “2024 Semiannual Report,”August 27, 2024, https://www.sse.com.cn/disclosure/listedinfo/announcement/c/new/2024-08-29/688107_20240829_UINW.pdf. Anlogic reportedly spends at least 40 percent of its revenue on research and development (R&D).45Gao, “Chinese FPGA Star.”

- Gowin Semiconductor (高云半导体): Gowin Semiconductor is gaining domestic market share, specifically in IoT, automotive, and industrial applications. Founded in 2014, Gowin has attracted multiple government-backed investments. In May 2022, Guangzhou Bay Area Semiconductor Group, a state-backed fund, led the most recent funding round and emerged as Gowin’s largest shareholder46.SEMI, “Gowin Semiconductor secures a significant series B+ funding round of 880 million yuan, embarking on a new journey in domestically-produced FPGA chips,” May 24, 2022, https://www.semi.org.cn/site/semi/article/e21a44a389a64449890c41f129553a6c.html. This funding is expected to be used for expanding R&D as well as target new markets.47SEMI. Gowin is the only PRC FPGA supplier with an automotive-grade FPGA certification.48SEMI.

- Shanghai Fudan Microelectronics Group (上海复旦): Fudan Microelectronics is a state-affiliated integrated circuit (IC) design company that originated from Fudan University in 1998.49Shanghai Fudan Microelectronics Group, “Introduction,” accessed March 27, 2025, https://www.fm-chips.com/shanghai-fudan-microelectronics-group-co-ltd-introduction.html. In 2024, Fudan Microelectronics spent roughly a third of its revenue on R&D.50Shanghai Fudan Microelectronics Group, “Results Announcement for the Year Ended 31 December 2024,” March 26, 2025, https://eng.fmsh.com/UpLoadFile/20250326/e_submission_result.pdf. Although the Big Fund does not appear to have invested directly in Fudan Microelectronics, the company receives investments from state-affiliated financial entities51CIQ Pro, “Ownership Detailed: Shanghai Fudan Microelectronics Group Company Limited (SEHK:1385, SHSE:688385),” accessed April 5, 2025, https://www.capitaliq.spglobal.com/web/client#company/PublicOwnershipDetailed?Id=4968433. and significant government research grants.52Shanghai Fudan Microelectronics Group, “2023 Interim Report,” September 22, 2023, 69, https://eng.fmsh.com/UpLoadFile/20230922/e01385.pdf.

- Shenzhen Pango Microsystems (紫光同创): Pango Microsystems is the largest FPGA supplier to Huawei and seeks to expand into advanced FPGAs.53Sina Finance, “This year’s most popular Chinese-made FPGA chip,” November 20, 2024, https://finance.sina.com.cn/jjxw/2024-11-20/doc-incwspwu2211604.shtml Pango has also attracted investments from government-backed entities.54PitchBook, “PitchBook Profile – Pango Micro,” PitchBook, last updated May 18, 2025, https://my.pitchbook.com/profile/571461-85/company/profile#investors; Unigroup Guoxin Microelectronics Co., Ltd., “2024 Semiannual Report,” August 2024, 131–32, https://q.stock.sohu.com/newpdf/202459387852.pdf. The firm reportedly dedicates 80 percent of its 800-plus staff to R&D.55Shenzhen Pango Microsystems Co., Ltd., “Company profile,” accessed March 29, 2025, https://www.pangomicro.com/about/index/.

- Hercules Microelectronics (京微齐力): Hercules Microelectronics, founded in 2017, focuses on FPGAs for AI acceleration, data centers, and electronic vehicles.56Hercules Microelectronics, “Hercules Microelectronics Company Profile,” accessed March 25, 2025, https://en.hercules-micro.com/index/index/about. Although not directly backed by the Big Fund, Hercules Microelectronics received funding from investment funds linked with the Beijing municipal government.57Jesse Allen, “Startup Funding: June 2022,” Semiconductor Engineering, July 6, 2022, https://semiengineering.com/startup-funding-june-2022/; CIQ Pro, “Private Ownership: Hercules Microelectronics,” accessed April 6, 2025, https://www.capitaliq.spglobal.com/web/client#company/privateOwnership?id=17514549.

These examples demonstrate the level of financial support the PRC government supplies to FPGA firms, both through the Big Fund and other initiatives. A significant portion of this funding is directed toward R&D efforts, enabling PRC FPGA firms to expand their capabilities and compete more effectively with established US FPGA firms. However, while Big Fund support appears to have played a key role in building PRC FPGA firms, it has not been able to drive long-term, sustainable growth. For example, its pre-IPO investment in Anlogic likely strengthened investor confidence in the firm and helped the company raise approximately $186.04 million.58Shanghai Anlogic Infotech Co., Ltd., “2021 Annual Report,” April 28, 2022, 32, https://file.finance.sina.com.cn/211.154.219.97:9494/MRGG/CNSESH_STOCK/2022/2022-4/2022-04-28/8127394.PDF. This capital infusion supported significant R&D efforts, resulting in six new chips being released in 2022.59Shanghai Anlogic Infotech Co., Ltd., “2022 Annual Report,” April 25, 2023, 11, https://file.finance.sina.com.cn/211.154.219.97:9494/MRGG/CNSESH_STOCK/2023/2023-4/2023-04-25/9058622.PDF. As a result, Anlogic revenue surged from $105.16 million to $154.83 million,60Shanghai Anlogic Infotech Co., Ltd., 103. with net profit of $8.89 million.61Shanghai Anlogic Infotech Co., Ltd., 184. However, as the semiconductor industry slowed between 2022 and 2023,62Wei Zhongyuan, “Phase One of the Big Fund announces two share reduction plans; the five-year recovery period is nearing its end,” Shenzhen Securities Times, July 2, 2024, https://www.stcn.com/article/detail/1246114.html. the Big Fund reduced its Anlogic holdings from roughly 39 million shares to 31 million shares63Shanghai Anlogic Infotech Co., Ltd., “2023 Annual Report,” April 27, 2024, 92, https://file.finance.sina.com.cn/211.154.219.97:9494/MRGG/CNSESH_STOCK/2024/2024-4/2024-04-27/10119946.PDF. and Anlogic experienced a substantial 2023 net loss of $27.87 million, primarily driven by weak downstream demand and its continued aggressive R&D spending of $54.3 million.64Shanghai Anlogic Infotech Co., Ltd., 104–5. The trend persisted in 2024, with Anlogic reporting another net loss of $28.54 million, despite reducing its R&D spend by about 7 percent.65Shanghai Anlogic Infotech Co., Ltd., “2024 Annual Report,” April 26, 2025, 112–13.

Figure 3. Anlogic’s revenue and profit have declined without sustained Big Fund investment

Anlogic’s recent performance highlights three key takeaways. First, Big Fund investments appear to have provided critical capital that enabled Anlogic to enter and compete in the FPGA market with rapid, extensive R&D. Second, Anlogic has struggled to sustain profitability through semiconductor market swings without ongoing capital support. Third, despite financial pressures, Anlogic and similar firms remain committed to aggressive R&D investment to enhance their competitiveness and improve their product portfolios, ultimately enabling them to offer high-quality FPGAs at lower costs.

Conclusion

The FPGA market is highly segmented and the substantial customization of FPGA designs needed for different applications can form a significant barrier to entry. However, rapid, large-scale PRC investment in lagging-edge semiconductors has established more than just the five FPGA design firms highlighted above and has increased substantial manufacturing capacity at lagging-edge process nodes, which will ramp up PRC FPGA production in the near future. The PRC FPGA firms described above collectively address a broad set of critical FPGA segments, with considerable support from the PRC government.

This development poses two principal concerns for the United States. First, these FPGAs will enable the PRC to develop new capabilities across its economy and for military purposes. Second, if geopolitics allows global technology standards and supply chains to remain integrated, US FPGA makers may struggle to compete with these new PRC players given the scale and degree of their government support. FPGAs are critical components in US defense equipment and underpin US critical infrastructures as well as significant economic activity. To protect US national security and economic interests, the US government should consider launching a dedicated effort to address the impact of PRC FPGA firms on the resilience of US FPGA supply chain.

About the Authors

Celine Lee holds a Master of Public Policy from the Harvard Kennedy School and previously held fellowships at the United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations and the American Institute in Taiwan (AIT).

Andrew Kidd holds a Master of Public Policy from the Harvard Kennedy School and was previously an engagement manager in the high-tech and public sector practices at McKinsey & Company.

Bruce Schneier is a security technologist and a fellow and lecturer at the Harvard Kennedy School.

Explore the program

The Atlantic Council’s Cyber Statecraft Initiative, part of the Atlantic Council Technology Programs, works at the nexus of geopolitics and cybersecurity to craft strategies to help shape the conduct of statecraft and to better inform and secure users of technology.