The Maduro-Hezbollah Nexus: How Iran-backed Networks Prop up the Venezuelan Regime

Key Points

- Too often, Hezbollah in Venezuela is characterized as only a potential terrorist threat. In reality, the Lebanese terrorist group has helped to turn Venezuela into a hub for the convergence of transnational organized crime and international terrorism.

- Hezbollah's crime-terror network in Venezuela has facilitated Iran's cooperation with the Maduro regime.

- The United States, allies, and international institutions must ramp up regional counterterrorism collaboration, crack down on illicit financial networks, and build stronger ties with Lebanese and other Arab communities in Latin America.

Introduction

In the face of another fated sham election in Venezuela, countries throughout the Americas and Europe are focusing on the many illicit tactics Nicolás Maduro uses to hold on to power. Top among them: the far-reaching illicit networks that prop up the Maduro regime. This includes armed groups that control vast swaths of territory, establishing a parallel state structure that conjoins the Maduro regime to international terrorism and transnational organized crime. In this environment, US policy shifted from “incrementalism” to “maximum pressure” in 2019, in an effort to constrain Nicolás Maduro’s grip on power in Venezuela.

This approach led to a March 2020 US Department of Justice (DOJ) announcement of multiple narcoterrorism indictments against the Maduro regime, including charges against Nicolás Maduro himself.1“Attorney General William P. Barr Delivers Remarks at Press Conference Announcing Criminal Charges Against Venezuelan Officials,” US Department of Justice, March 26, 2020, https://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/attorney-general-william-p-barr-delivers-remarks. Two months later, the DOJ indicted a former member of Venezuela’s National Assembly, the Syrian-Venezuelan dual national Adel El Zebayar, for allegedly working with Maduro and several top regime leaders in Venezuela on a narcoterrorism conspiracy that involved dissidents of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), drug cartels in Mexico, the Islamic Republic of Iran, Syria, and the Lebanese terrorist group Hezbollah.2“Former Member of Venezuelan National Assembly Charged with Narco-Terrorism, Drug Trafficking, and Weapons Offenses,” US Department of Justice, May 27, 2020, https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdny/pr/former-member-venezuelan-national-assembly-charged.

These actions by the DOJ highlight a debate in the United States and Europe about the presence and role of Hezbollah in Venezuela and Latin America overall. Too often this debate is characterized by simplistic views that see Hezbollah in Venezuela as only a potential terrorist threat. Equally, other views diminish the role and relationship between Hezbollah and the Maduro regime altogether. Neither position captures the nuance of how Hezbollah operates in Venezuela and neighboring countries, nor does it establish a baseline for understanding how Hezbollah fits into the larger strategic picture of the illicit networks propping up the Maduro regime, and its relationship with Iran.

Adding to this deficit of knowledge is that, for many Latin American policymakers, Hezbollah is viewed as a distant problem far from local concerns. Likewise, for US and European policymakers, Latin America is not a top priority for counterterrorism efforts focused mostly on the Middle East and North Africa. This state of affairs has allowed legal and policy vacuums to arise regionwide, which the Maduro regime and Hezbollah have exploited to turn Venezuela into a central hub for the convergence of transnational organized crime and international terrorism.3Financial Nexus of Terrorism, Drug Trafficking, and Organized Crime, Subcommittee of Terrorism and Illicit Finance, US House of Representatives (2018) (testimony of Joseph M. Humire), https://financialservices.house.gov/uploadedfiles/03.20.2018_joseph_humire_testimony.pdf.

Hezbollah and Crime-Terror Convergence

Hezbollah is responsible for carrying out terrorist attacks in Israel, Lebanon, Kuwait, Argentina, Panama, United Kingdom, Saudi Arabia, and Bulgaria.4For a detailed discussion, see Matthew Levitt, Hezbollah: The Global Footprint of Lebanon’s Party of God (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2015). In Latin America, it is infamously known for the bombings of the Israeli embassy in 1992 and the Asociación Mutual Israelita Argentina (AMIA) Jewish community center in 1994, both in Buenos Aires, collectively killing one hundred and fourteen people and injuring hundreds more. The AMIA attack shocked many counterterrorism analysts at the time because it was the first terrorist attack by Hezbollah outside of Lebanon or the Middle East. The long arm of Iran and Hezbollah’s terror networks is also suspected of downing the Alas Chiricanas Flight 00901 in Panama the day after the 1994 bombing in Buenos Aires, killing all twenty-one passengers aboard.

The Hezbollah terror network that moved from Lebanon to Colombia to the Tri-Border Area, between Paraguay, Brazil, and Argentina—to carry out the 1994 AMIA attack—is still active today. The work of the late Argentine special prosecutor Alberto Nisman ensured that Latin America remembers this fact.5“Nisman Report (Dictamina) on Sleeper Cells,” AlbertoNisman.org, March 4, 2015, http://albertonisman.org/nisman-report-dictamina-on-sleeper-cells-full-text/. Since the AMIA attack, Hezbollah’s External Security Organization (ESO) or “Unit 910,” responsible for its extraterritorial operations, has successfully co-opted many Lebanese families throughout Central and South America, as well as the Caribbean.

Throughout the years, Hezbollah’s ESO has morphed from merely a terrorist network in Latin America to engage in the region’s most lucrative illicit enterprise: narcotics. Of the more than two thousand individuals and entities around the world designated by the US government as foreign narcotics kingpins, almost two hundred are affiliated with or connected to Hezbollah.6Financial Nexus of Terrorism, Drug Trafficking, and Organized Crime, 3. As of August 5, 2020, there are 2,140 individuals and entities identified as “Foreign Narcotics Kingpins” by the US Department of Treasury Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) persuant to the Kingpin Act of 2000. Its growing involvement in massive money-laundering schemes and multi-ton shipments of cocaine led the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) to name a subunit of Hezbollah’s ESO that is sometimes referred to as the “Business Affairs Component,” or BAC.7“DEA And European Authorities Uncover Massive Hizballah Drug and Money Laundering Scheme,” United States Drug Enforcement Administration, press release, February 1, 2016, https://www.dea.gov/press-releases/2016/02/01.

Throughout the years, Hezbollah’s ESO has morphed from merely a terrorist network in Latin America to engage in the region’s most lucrative illicit enterprise: narcotics.

Hezbollah’s involvement in drug trafficking is not new. Its criminal activities were established by the same founder as the ESO, Imad Mugniyeh, the deceased Hezbollah leader who is also implicated in the AMIA terrorist attack in Argentina. Hezbollah’s transnational crime portfolio is currently led by the secretary general’s cousin and Hezbollah’s envoy to Iran, Abdallah Safieddine, who shares this portfolio with Adham Hussein Tabaja.8“Treasury Sanctions Hizballah Front Companies and Facilitators in Lebanon and Iraq,” US Department of Treasury, press release, June 10, 2015, https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/jl0069.aspx. A prominent Hezbollah member who owns its media propaganda arm, Tabaja has set up many investment mechanisms and cash- and credit-intensive businesses to launder Hezbollah’s illicit proceeds. The most notable is Al-Inmaa Engineering and Contracting, based in Lebanon and Iraq, whose financial manager, Jihad Muhammad Qansu, has a Venezuelan passport.9“Treasury Targets Hizballah Financial Network in Africa and the Middle East,” US Department of Treasury, February 2, 2018, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm0278. Together, Tabaja and Safieddine are tied to a vast transnational criminal network that includes an array of businesses in Latin America—namely in textiles, beef, charcoal, electronics, tourism, real estate, and construction—used to launder Hezbollah’s illicit funds. In October 2018, the Justice Department elevated Hezbollah’s status in the United States by listing it as one of the top five transnational criminal organizations (TCO).10“Attorney General Sessions Announces New Measures to Fight Transnational Organized Crime,” US Department of Justice, press release, October 15, 2018, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/attorney-general-sessions-announces. Naming Hezbollah alongside three major Mexican cartels and the Central American gang MS-13 was a wake-up call for Latin America to realize that, in today’s age, Hezbollah is equal to the cartels in organized crime and terror.

The National Defense University (NDU) has been ahead of the curve in assessing the convergence of organized crime and terrorism. In the foreword to NDU’s seminal 2013 publication on the topic, the former NATO Supreme Allied Commander and Atlantic Council board member Admiral James Staviridis described the convergence.11Michael Miklaucic and Jacqueline Brewer, eds. Convergence: Illicit Networks and National Security in the Age of Globalization (Washington, DC: National Defense University Press, 2013), https://ndupress.ndu.edu.

[Transnational] organizations are a large part of the hybrid threat that forms the nexus of illicit drug trafficking—including routes, profits, and corruptive influences—and terrorism, both homegrown as well as imported Islamic terrorism…They have achieved a degree of globalized outreach and collaboration via networks, as well as horizontal diversification.

This description is apt for Hezbollah, which inherently has a multidimensional model for its organizational structure with foreign relations and social-service sectors, a political party, and media groups—but blends these legitimate activities with its clandestine illicit networks, both in Lebanon and worldwide. Most of the Lebanese diaspora worldwide is not involved in these criminal or terrorist activities; however, given that approximately 14 percent of Lebanon’s gross domestic product (GDP) comes from remittances, Hezbollah’s ESO is actively infiltrating these communities to build financial support networks abroad.12“Remittances Markedly Boost Lebanon’s GDP,” An-Nahar, May 18, 2017, https://en.annahar.com/article/586292. In Latin America, these support networks are nested primarily in Lebanese and Arab communities, of which the largest in the region reside in Brazil, Argentina, Colombia, and Venezuela.

Naming Hezbollah alongside three major Mexican cartels and the Central American gang MS-13 was a wake-up call for Latin America to realize that, in today’s age, Hezbollah is equal to the cartels in organized crime and terror.

Hezbollah’s Support Network in Venezuela and Ties to the Maduro Regime

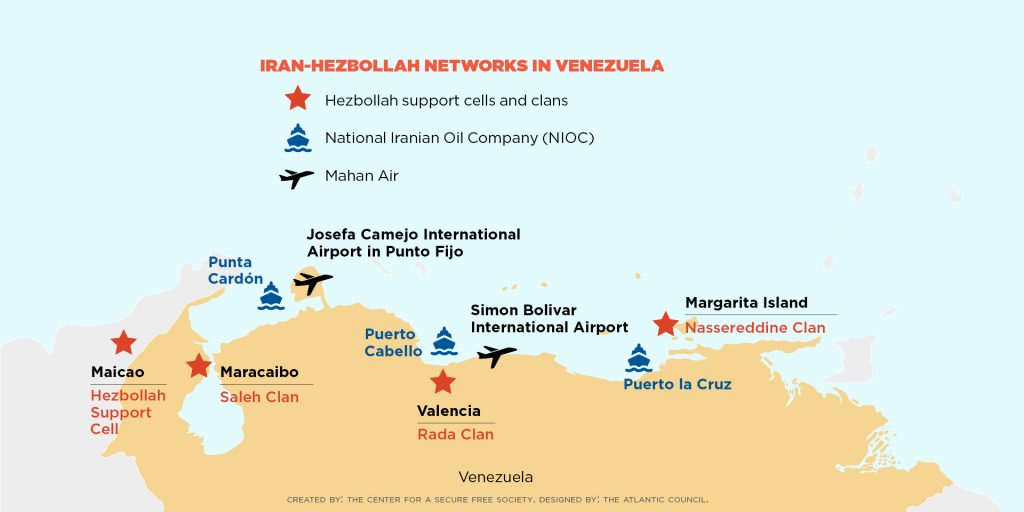

For more than one hundred and fifty years, waves of mass migration arrived from Lebanon, Syria, and Armenia to Venezuela. The first wave arrived in the late nineteenth century, during the Ottoman era.13Ignacio Klich and Jeffrey Lesser, “Introduction: ‘Turco’ Immigrants in Latin America” in Special Issue: “Turco” Immigrants in Latin America, The Americas 53.1 (1996), 1–14. In the early twentieth century, another wave of mass migration arrived in Venezuela from Lebanon, mostly Maronite Christians, who settled largely in Margarita Island, Puerto Cabello, Punto Fijo, and La Guaira.14Ibid. By 1975, at the onset of the Lebanese civil war, Venezuela became well known as a prominent destination for those seeking to escape the harsh conditions of the war.

Venezuela’s vibrant economy and relatively high standard of living at the time offered a beacon for many Lebanese. While many in the Lebanese-Venezuelan community have made significant contributions to society, this historic refugee route to Venezuela was exploited by Hezbollah to build support networks. Often without the larger Lebanese community aware of this clandestine activity, an “army” of logistical professionals—entrepreneurs, lawyers, accountants, and others—emerged within the diaspora as a support network in Venezuela who help to raise, conceal, move, and launder illicit funds for Hezbollah, some of which is used to advance its terror operations worldwide (as shown in the “Saleh Clan” subsection below).

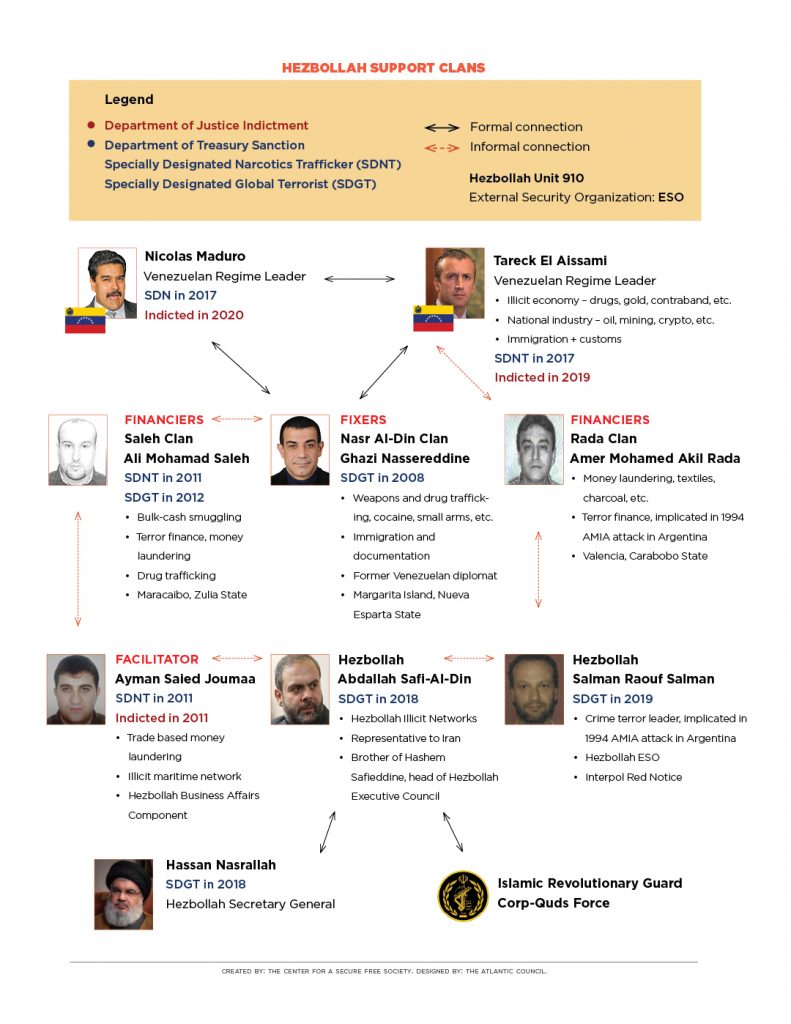

In Venezuela, Hezbollah’s support network operates through compartmentalized, familial clan structures that embed into the Maduro regime-controlled illicit economy and the regime’s political apparatus and bureaucracy. Many of the clans are assimilated within the Venezuelan state and society through the robust Lebanese and Syrian communities that extend to neighboring Colombia.

In Venezuela, Hezbollah’s support network operates through compartmentalized, familial clan structures that embed into the Maduro regime-controlled illicit economy and the regime’s political apparatus and bureaucracy.

The Saleh Clan

Hezbollah’s crime-terror network in Colombia and Venezuela was revealed in 2011 after a two-year investigation that resulted in one hundred and thirty arrests and the seizure of $23 million of illicit funds moved through West Africa into Lebanon through the Lebanese Canadian Bank.15“Treasury Targets Major Money Laundering Network Linked to Drug Trafficker Ayman Joumaa and a Key Hizballah Supporter in South America,” US Department of the Treasury, press release, June 27, 2012, https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/pages/tg1624.aspx. In one of the most significant cases on trade-based money laundering, Operation Titan took down a transregional cocaine-trafficking and mass money-laundering ring run by Hezbollah through local facilitators in Colombia, led by Ayman Saied Joumaa. A Colombian-Lebanese drug kingpin, Ayman Joumaa, was indicted in the United States by a federal grand jury for trafficking cocaine with Los Zetas in Mexico and, according to the Treasury Department, runs an extensive maritime shipping network tied to Hezbollah.16“U.S. Charges Alleged Lebanese Drug Kingpin with Laundering Drug Proceeds for Mexican and Colombian Drug Cartels,” US Attorney’s Office, Eastern District of Virginia, December 13, 2011, https://www.justice.gov/archive/usao/vae/news/2011/12/20111213joumaanr.html; “Treasury Sanctions Maritime Network Tied to Joumaa Criminal Organization,” US Department of Treasury, press release, October 1, 2015, https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/jl0196.aspx.

Operation Titan started in 2008 when US and Colombian investigators were targeting a Medellín-based cartel called La Oficina de Envigado, or “La Oficina.”17Celina Realuyo, “The Terror-Crime Nexus: Hezbollah’s Global Facilitators,” Prism 5, 1, National Defense University, 2015, https://cco.ndu.edu/Portals/96/Documents/prism/prism_5-1/The_Terror_Crime_Nexus.pdf. Over the two-year investigation, authorities unraveled the many connections La Oficina had with the large Lebanese community along the Caribbean coast in Colombia.18Matthew Levitt, “Hezbollah’s Criminal Networks: Useful Idiots, Henchmen, and Organized Criminal Facilitators,” National Defense University, October 25, 2016, https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/uploads/Documents/opeds/Levitt20161025-NDU-chapter.pdf. These connections were strengthened by Hezbollah facilitators who established a complex maze of cross-border trade and bulk-cash couriers between Colombia and Venezuela.

A prominent Shia businessman and Hezbollah operative, Ali Mohamad Saleh, led the cross-border crime-terror network in Colombia and Venezuela uncovered during Operation Titan. Ali Mohamad and his brother, Kassem Mohamad Saleh, were designated as terror financiers in 2012 by Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), while Ali Mohamad Saleh was also designated as a narcotics kingpin a year earlier. For many years, the Saleh clan controlled the illicit markets for drugs, weapons, contraband, bulk-cash smuggling, and money laundering in Maicao, Colombia (see below for more on Maicao) close to the northern border with Venezuela. Local drug cartels in western Venezuela controlled by members of the Maduro regime, prominently in Zulia State, benefit from this illicit cross-border trade once managed by the Saleh clan.19Los Leal drug cartel in the San Francisco municipality, along Lake Maracaibo, is considered to be the fastest-growing criminal group in Zulia State. According to several Venezuela organized-crime experts, Los Leal is considered a “hybrid state-criminal structure” that benefits from the institutional protection and support of the Maduro regime’s state security forces. According to shopkeepers in Maicao, the Saleh brothers fled overnight to Venezuela after being sanctioned in 2012, and are now reportedly in Maracaibo working with another prominent Lebanese clan embedded into the Maduro regime bureaucracy.20Abraham Mahshie, “Hezbollah Financing Evolves Beyond Colombia’s Muslim Communities,” World-Wide Religious News, December 19, 2013, https://wwrn.org/articles/41379/.

The Nassereddine Clan

Ghazi Nassereddine was sanctioned by OFAC in 2008 for his ties to Hezbollah and listed as a person of interest by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in 2015.21“Treasury Targets Hizballah in Venezuela,” US Department of the Treasury, press release, June 18, 2008, https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/pages/hp1036.aspx; “FBI Adds Lebanese Man to Seeking Information–Terrorism List,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, press release, January 29, 2015, https://www.fbi.gov/contact-us/field-offices/miami/news/press-releases/. Ghazi’s older brother, Abdallah Nassereddine, is a prominent businessman on Margarita Island who owns several real-estate properties and commercial centers on the once-popular vacation destination in Venezuela.22Iran’s Influence and Activity in Latin America, Subcommittee on the Western Hemisphere, Peace Corps, and Global Narcotics Affairs, US Senate (2012) (testimony by Ambassador Roger Noreiga), https://www.foreign.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Roger_Noriega_Testimony1.pdf. Originally from Lebanon, the Nasserredine clan rose to political prominence in Venezuela once Hugo Chávez became president. Ghazi entered the Foreign Ministry in Venezuela, attaining official diplomatic status, and Abdallah became an important, although low-profile, figure in the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV), serving as a regional coordinator for Nueva Esparta State.23Iran and Hezbollah in the Western Hemisphere, Subcommittee on the Western Hemisphere, US House of Representatives (2015) (testimony by Joseph M. Humire), https://docs.house.gov/meetings/.

While stationed at the Bolivarian Republic’s embassy in Damascus, Syria, Ghazi Nassereddine helped arrange meetings between senior Venezuelan officials and high-ranking Hezbollah operatives. According to DEA informants, in or about 2009, Ghazi fixed a meeting in Syria between Hezbollah and Venezuela’s then-Interior Minister Tareck El Aissami, and the Venezuelan military counterintelligence chief, Hugo Carvajal Barrios.24In a DOJ indictment dated May 27, 2020, by the Southern District of New York against a former member of the Venezuelan National Assembly, a DEA special agent discussed this 2009 meeting in Syria between a Hezbollah operative and Tareck El Aissami and Hugo Carvajal, on pg. 10 of U.S. v. Adel El Zebayar. According to the indictment, the DEA investigation was supported by one confidential witness and at least two confidential sources. The meeting allegedly prompted a cocaine-for-weapons scheme between the FARC and Hezbollah that materialized in 2014 when a Lebanese cargo plane full of small arms (AK-103s, rocket-propelled grenade launchers, etc.) arrived at the presidential hangar (rampa 4) of the Maiquetia International Airport in Caracas.25Ibid, 16–17. The weapons were reportedly a partial payment for the cocaine the FARC provided to the Maduro regime, and was transferred to a military base in Guárico, Venezuela.

Still a close associate of Nicolás Maduro, the former diplomat Ghazi Nassereddine currently runs the Venezuelan think tank Global AZ and has taken several trips to France, Germany, and Italy since leaving Syria in 2011.26A detailed mapping of the Nassereddine network in Venezuela has been done by the author and a field research team in Central and South America. Ghazi Nassereddine often travels under an alias and with various passports and in private flights. Prior to 2014, Ghazi traveled primarily to France, Germany, and Italy with a 2007 trip to Iran and Cuba. Author interviews with Colombian police officials in December 2019 in Bogota, Colombia, along with immigration records from Venezuela, corroborated these findings and field research. Other members of the Nassereddine clan are suspected of running political indoctrination, paramilitary training, and weapons and drug smuggling in Venezuela. One Nassereddine clan member is also believed to be in charge of security for Venezuela’s current Minister of Petroleum and former Vice President Tareck El Aissami.27Author interview with Carlos Papparoni on February 3, 2020, in Washington, DC. Deputy Papparoni was appointed by Juan Guaido as a representative in the interim Venezuelan government’s Office of Regional Cooperation against Money Laundering and Corruption, and later as commissioner for counterterrorism and CTOC.

In the counterterrorism lexicon, the Nassereddine clan would be characterized as “fixers”—or, in the case of Ghazi, a “super fixer”—because the members aren’t part of Hezbollah’s hierarchical chain of command, but are integral to organizing support networks in Venezuela that connect Hezbollah to the Maduro regime. These fixers provide distance and a measure of deniability for Hezbollah leaders to hide their connection to the Maduro regime, and establish pathways to the regime’s bureaucracy and political apparatus in Venezuela.

…the Nassereddine clan [characterized as ‘fixers’ in the counterterrorism lexicon] provides distance and a measure of deniability for Hezbollah leaders to hide their connection to the Maduro regime.

The Rada Clan

The city of Maicao is a historic commercial hub in La Guajira department in Colombia, with a large concentration of Lebanese immigrants dating back to the nineteenth century. In 2017, Colombian immigration authorities deported one of its residents, a Hezbollah financier and Venezuelan-Lebanese dual national, Abdala Rada Ramel, who was suspected of running a drug-trafficking and contraband-smuggling ring from Maicao to Cartagena.28“Policía Expulsó del País Ciudadano Libanés Vinculado con Narcotráfico,” El Tiempo, October 27, 2017, https://www.eltiempo.com/justicia/policia-expulso-del-pais-ciudadano-libanes-vinculado-con-narcotrafico-145546.

He is a prominent member of the Rada clan, known to have close ties to a high-level Hezbollah leader. According to Semana, a well-known Colombian magazine, in his initial interrogation, Abdala Rada Ramel revealed that his illicit activities in Colombia were in coordination with his “supervisor” Salman Raouf Salman, a shadowy Hezbollah ESO leader who has been implicated in numerous terrorist operations worldwide.29“El Colombiano de Hizbulá,” Semana, July 7, 2018, https://www.semana.com/nacion/articulo/.

Cutting his teeth in Argentina as Hezbollah’s on-the-ground coordinator for both bombings in Buenos Aires in 1992 and 1994, Salman Raouf Salman—whose alias is Samuel Salman El Reda El Reda—continues to direct Hezbollah’s ESO crime-terror network in Latin America, including in Venezuela.30“Salman Raouf Salman, el Terrorista de Hezbollah que Coordina el Narcotráfico y el Lavado de Dinero en América Latina,” Infobae, August 1, 2018, https://www.infobae.com/america/america-latina/2018/08/01/. With an international arrest warrant issued by Argentina in 2009, an OFAC terrorist designation in 2019, and a $7 million reward for information leading to his capture, Salman Raouf Salman, along with his brother Jose Salman El Reda El Reda, is credited with building Hezbollah’s support networks in Latin America.31“OFAC Recent Actions,” US Department of the Treasury Resource Center, https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/OFAC-Enforcement/Pages/20190719.aspx; “Salman Raouf Salman: Wanted,” US Department of State, https://rewardsforjustice.net/english/salman_salman.html.

Salman Raouf Salman’s ties to the Rada clan date back to the 1994 AMIA attack. Argentine authorities suspect a Venezuelan-Lebanese dual national named Amer Mohamed Akil Rada of being involved in the Hezbollah attack of the AMIA building.32Author interviews with Argentine security officials on July 20, 2019, in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Amer Mohamed, who is also suspected of being involved in the 1992 terrorist bombing of the Israeli embassy in Buenos Aires, is alleged to have worked closely with Salman Raouf Salman throughout the 1990s to case various targets for Hezbollah’s ESO in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, and Venezuela.

Decades later, a fifty-three-year-old Amer Mohamed Akil Rada, has set up small import-export businesses in Panama, sending textiles to Colombia and charcoal to Lebanon, with as much as 80 percent of the proceeds used to support Hezbollah.33George Chaya, “Interpol Detecta Actividades Ilícitas de Hezbollah en Colombia,” Infobae, April 7, 2018, https://www.infobae.com/america/colombia/2018/04/07/interpol-detecta-actividades-ilicitas-de-hezbollah-en-colombia/. In counternarcotics circles, charcoal is often called “black cocaine” because it is frequently used to disguise the transfer of cocaine.34For more on Hezbollah’s use of “black cocaine,” see Emanuele Ottolenghi, “How Hezbollah Collaborates with Latin American Cartels,” The Dispatch, September 22, 2020, https://thedispatch.com/p/how-hezbollah-collaborates-with-latin. Akil Rada’s relatives continue to operate in Venezuela and are involved in the cryptocurrency industry, which is controlled by the Maduro regime.35Samer Akil Rada, the brother of Amer Mohamad Akil Rada, operates various cryptocurrency companies in Venezuela, namely in Valencia. Joselit de la Trinidad Ramirez Camacho, the Maduro regime’s crypto chief responsible for the state-backed petro, was recently indicted by DOJ and has a $5-million bounty for helping regime officials evade OFAC sanctions.36“HSI Adds Venezuelan Official to Most Wanted List, $5M Reward Offered for Information Leading to His Arrest, Conviction,” US Immigration and Customs Enforcement, press release, June 1, 2020, https://www.ice.gov/news/releases/. The indictment states that Ramirez Camacho has “deep political, social, and economic ties to multiple alleged narcotics kingpins, including Tareck El Aissami.”37Jose Antonio Lanz, “US Gov Puts $5 Million Bounty on Venezuela’s Head of Crypto,” Decrypt, June 1, 2020, https://decrypt.co/30898/us-gov-million-dollar-bounty-venezuela-crypto-chief. The Rada clan connections to the Maduro regime are nested in this relationship with Tareck El Aissami.

The Rada, Saleh, and Nassereddine clans are part of a much larger global illicit network of fixers, financiers, and facilitators for Hezbollah, operating out of Venezuela with protection from the Maduro regime. Members of two of the three clans have been designated by the US Treasury Department as global terrorists for their ties to Hezbollah.38Ghazi Nasr al Din was designated a specially designated global terrorist (SDGT) by Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) on June 18, 2008; Ali Mohamad Saleh was designated a SDGT by OFAC on June 27, 2012. However, no member of the Rada clan has been designated or sanctioned by the US Department of Treasury to date. Unlike the Nassereddine clan, members of the Rada clan and Saleh clan are not formally a part of the Maduro regime; however, they each manage aspects of the illicit economies of drugs, weapons, contraband, smuggling, and money laundering between Venezuela, Lebanon, and Syria. Each provides a specific service and comparative advantage for connecting Hezbollah to the Maduro regime, acting as “convergence points”to the regime-controlled illicit economy and specific sectors of its licit economy, establishing a degree of plausible deniability for both the Maduro regime and Hezbollah’s leadership, which both deny any direct cooperation.39“US Strategy to Combat Transnational Organized Crime, Addressing the Threats to National Security,”White House, July 2011; Nicolás Maduro, “Esto Dijo Maduro sobre Supuestos Vínculos con Hezbollah,” February 8, 2019, YouTube video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=238&v=VgipIhoczwE&feature=emb_logo.

The Rada, Saleh, and Nassereddine clans are part of a much larger global illicit network of fixers, financiers, and facilitators for Hezbollah, operating out of Venezuela with protection from the Maduro regime.

The US-Colombia joint Operation Titan, which, by 2014, led to ten separate but interrelated kingpin designations by OFAC and three federal indictments by DOJ, described some of these convergence points that established air and sea bridges between Venezuela, Iran, and Hezbollah.40Robert “J. R.” McBrien, “Financial Tools and Sanctions: Following the Money and the Joumaa Web,” Journal of Complex Operations, May 24, 2016, https://cco.ndu.edu/News/Article/780264/. As the US “maximum pressure” campaign ensues, this bridge becomes increasingly important to maintain a transregional threat network that enables Iran and Hezbollah to prop up the Nicolás Maduro regime in Venezuela and the Bashar al-Assad regime in Syria.

In Venezuela, the logistical air bridge between Caracas, Damascus, and Tehran is what Maduro protects and has served profitable for Hezbollah and Iran.

From Syria to Venezuela

Iran and Hezbollah’s support to the Maduro regime in Venezuela follows the strategy of its support to Bashar al-Assad in Syria to protect the logistical foothold of Iran’s land bridge through the Levant. In Venezuela, the logistical air bridge between Caracas, Damascus, and Tehran is what Maduro protects and has served profitable for Hezbollah and Iran.

In southwestern Syria, more than three hundred thousand Venezuelans reside in a city called As-Suwayda.41“Colombia en la Mira de Hizbulá con el Apoyo de Venezuela,” Semana, October 4, 2020, https://www.semana.com/nacion/articulo/integrantes-de-hizbula. Many of them dual nationals, comprising almost two thirds of the primarily Druze governorate in Syria also called As-Suwayda. Known in Syria as “little Venezuela,” As-Suwayda is currently occupied by Russian military forces, Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), and Hezbollah militants that are affiliated with 60 percent of all armed groups in the province defending Bashar al-Assad.42“Divide and Conquer: The Growing Hezbollah Threat to the Druze,” Middle East Institute, October 21, 2019, https://www.mei.edu/publications/divide-and-conquer-growing-hezbollah-threat-druze.

Hezbollah’s defense of the Assad regime in Syria is controversial in Lebanon. Since Hezbollah’s inception, Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah insists on denying the group’s growing global footprint in the world of transnational organized crime in order to maintain legitimacy in Lebanon—even to the point of admitting Hezbollah’s financial support from Iran in order to distract from its other illicit sources of revenue.43Dr. Majid Rafizadeh, “In First, Hezbollah Confirms All Financial Support Comes from Iran,” Al Arabiya English, June 25, 2016, https://english.alarabiya.net/en/features/2016/06/25/In-first-Hezbollah-s-Nasrallah-confirms-all-financial-support-comes-from-Iran. Along these same lines, Nasrallah repeatedly emphasized that Hezbollah has no interests outside of Lebanon. But, in 2013, he publicly confirmed Hezbollah’s support of the Assad regime, in a speech in which he called Syria the “backbone” of the axis of resistance.44Marisa Sullivan, “Middle East Security Report 19: Hezbollah in Syria,” Institute for the Study of War, 2014, http://www.understandingwar.org/sites/default/files/Hezbollah_Sullivan_FINAL.pdf. This public support broke with decades of denial, and laid bare Hezbollah’s global interests outside of Lebanon.

Across the Atlantic, similar support is mounting by Iran and Hezbollah for the Maduro regime in Venezuela.45Colin P. Clark, “Hezbollah Is in Venezuela to Stay,” Foreign Policy, February 9, 2019, https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/02/09/hezbollah-is-in-venezuela-to-stay/. Venezuela’s strategic location in South America and at the crossroads of the Caribbean provides Iran and Hezbollah with an ability to diminish their geographic disadvantage against the United States. To hide this relationship, Chávez, and then the Maduro regime, provided dual identities to some Middle Easterners, building a clandestine network that provides intelligence, training, funds, weapons, supplies, and know-how to both the Maduro and Assad regimes.46Scott Zamost, et al., “Venezuela May Have Given Passports to People with Ties to Terrorism,” CNN, February 14, 2017, https://www.cnn.com/2017/02/08/; Sebastian Rotella, “The Terror Threat and Iran’s Inroads in Latin America,” ProPublica, July 11, 2013, https://www.propublica.org/article/the-terror-threat-and-irans-inroads-in-latin-america.

The aforementioned Lebanese-Venezuelan-Colombian clans are part of this transregional threat network that provides support to Hezbollah’s illicit activities and, equally, establishes a logistical base in Venezuela that allows the Maduro regime and associated criminal groups, including FARC dissidents and ELN guerrillas, to expand their operations.47Douglas Farah and Caitlyn Yates, “Maduro’s Last Stand,” IBI Consultants, May 2019, https://www.ibiconsultants.net/_pdf/maduros-last-stand-final-publication-version.pdf. The Maduro regime’s reliance on illicit networks is enhanced by Hezbollah’s transregional nature, while the Lebanese terror group benefits from state support in Venezuela to move its illicit funds and personnel in and out of the region. Combined, Hezbollah has helped the Maduro regime become the central hub for the convergence of transnational organized crime and international terrorism in the Western Hemisphere, multiplying the logistical and financial benefits for both.

Pariah States: Iran and Venezuela

Recent nationwide shortages of gasoline have added to the complexity of the crisis in Venezuela. Despite having the largest reserves of petroleum in the world, the state-owned oil enterprise, Petroleós de Venezuela (PDVSA), cannot refine its heavy crude due to mismanagement and corruption, leading to mass shortages and pent-up demand. In April 2020, the Maduro regime turned to Iran to partner in helping fix the oil refineries on the Paraguana peninsula, and to provide much-needed fuel to Venezuela. The newly minted oil minister, Tareck El Aissami, and the regime’s special envoy to Iran, Lebanese-Colombian businessman Alex Saab, seemingly worked out a gold-for-gas deal with Tehran.48Angus Berwick, “Detained Colombian Businessman was Negotiating with Iran for Venezuela, Lawyers Say,” Reuters, August 28, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-venezuela-iran/detained-colombia-businessman-was-negotiating-with-iran-for-venezuela-lawyers-say-idUSKBN25O1Q9.

Shortly after, in a period of a month and a half, the Iranian airline, Mahan Air, flew seventeen flights and the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) sailed five tankers from Iran to Venezuela to provide parts from China, Iranian technicians, and approximately 1.5 million barrels of gasoline to the fuel-starved Maduro regime.49Joseph Humire, “Iran, Turkey, and Venezuela’s Super Facilitator: Who is Alex Saab?” Center for a Secure Free Society, June 30, 2020, https://www.securefreesociety.org/research/who-is-alex-saab/. Months later, the refineries on the Paraguana peninsula still do not operate, and Venezuela is once again facing fuel shortages. But, according to Bloomberg, the Islamic Republic received almost half a billion dollars’ worth (nine tons) of gold bars as payment.50Patricia Laya and Ben Bartenstein, “Iran is Hauling Gold Bars out of Venezuela’s Almost-Empty Vaults,” Bloomberg, April 30, 2020, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-04-30/iran-is-hauling-gold-bars-out-of-venezuela-s-almost-empty-vaults.

The Iranian entities involved in this reported gold-for-gas scheme—namely Mahan Air, NIOC, and the Islamic Republic of Iran Shipping Lines (IRISL)—are all sanctioned by OFAC for connections to Iran’s feared clerical army, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). The nature of the IRGC and these state-owned or controlled entities raises a concern for potential dual-use operations, which have less of a commercial or humanitarian intent and are more militaristic in their ambitions.51For a more specific discussion, see Joseph Humire, “Iran and Venezuela’s Strategic Challenge to Sanctions,” Hill, August 31, 2020, https://thehill.com/opinion/international/514104-iran-and-venezuelas-strategic-challenge-to-sanctions. A civil-forfeiture complaint filed in a district court in Washington, DC, suggests that the IRGC is behind the fuel shipments to Venezuela, citing the corporate records of four additional Liberian-flagged tankers from Iran that were stopped from arriving in Venezuela.52“Warrant and Complaint Seek Seizure of All Iranian Gasoil Aboard Four Tankers Headed to Venezuela Based on Connection to IRGC,” US Department of Justice Office of Public Affairs, July 2, 2020, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/warrant-and-complaint-seek-seizure-all-iranian-gasoil-aboard-four-tankers-headed-venezuela. The contents of these tankers were seized by the United States in what has been described as the “largest U.S. seizure of Iranian fuel” to date.53“Largest U.S. Seizure of Iranian Fuel from Four Tankers,” US Department of Justice Office of Public Affairs,August 14, 2020, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/largest-us-seizure-iranian-fuel-four-tankers#:~:text=The%20Justice%20Department%20today%20announced,that%20was%20bound%20for%20Venezuela.

Much like in Syria, [the ability of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps] to operate in Venezuela is due to the heightened capability of Hezbollah’s support network.

Much like in Syria, the IRGC’s ability to operate in Venezuela is due to the heightened capability of Hezbollah’s support network. Hezbollah’s influence within, and infiltration of, Lebanese expat communities gives Iran a gateway to grow its footprint in Venezuela. Prominent businessmen, such as Alex Saab, are needed to facilitate this relationship with Iran because of their language, culture, and in-depth understanding of the Middle East. The June 2020 arrest in Cape Verde, off the coast of West Africa, and possible extradition of Saab to the United States for eight counts of money laundering has forced the Maduro regime to turn to other facilitators to manage the Iran portfolio.

One likely candidate is Lebanese-Venezuelan businessman Majed Khalil Mazjoub, who, along with his brother, Khaled, has amassed an empire in Venezuela in the shadows of the Chávez and Maduro regimes.54The Khalil Mazjoub brothers first gained notoriety in 2015 when they were identified as part of the company that owned the Cessna Citation 500 jet mentioned in the “Narcosobrinos” case, a high-profile criminal case against the nephews of Maduro’s wife, Celia Flores, who are currently serving an eighteen-year sentence in New York for drug trafficking. The Khalil Mazjoub brothers also reportedly received many preferential business deals from the Evo Morales regime in Bolivia, according to a 2017 legislative investigation by a Bolivian senator.55In 2017, Bolivian Senator Arturo Murillo, who is now the minister of government in Bolivia, launched a legislative investigation on Khaled Khalil Mazjoub’s business dealings with the Evo Morales government. Then-Senator Murillo stated that Khaled Mazjoub was contracted by the Bolivian state-owned oil and gas company YPFB in 2016. Immigration records from Bolivia show that Khaled Khalil Mazjoub traveled to La Paz at least seven times in the last five years, including a trip to Bolivia with his brother in 2015.56Bolivian immigration documents are in the author’s possession. A close relative of the Khalil Mazjoub brothers in Lebanon, former Lebanese Finance Minister Ali Hassan Khalil, was recently sanctioned by OFAC for his “material support to Hezbollah” and other corruption charges.57Treasury Targets Hizballah’s Enablers in Lebanon,” US Department of Treasury, press release, September 8, 2020, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm1116. A master of Middle Eastern networking with intimate knowledge of Venezuelan kleptocracy, Majed Khalil Mazjoub has the trust, access, and placement in Venezuela to help Iran and the Maduro regime continue their strategic cooperation should Alex Saab be sent to a US prison.

The dual-use nature of Iran’s cooperation with the Maduro regime, layered with the illicit finance connections of its facilitators and Hezbollah’s established crime-terror network in Venezuela, creates a tier-one national security concern for the United States—one that is multifaceted and requires a robust response.

Part of this cooperation is a new Iranian supermarket called “Megasis,” launched in Caracas in July. According to the Wall Street Journal, the supermarket is an offshoot of an Iranian retail chain, Etka, that is a subsidiary of the Ministry of Defense and Armed Forces Logistics (MODAFL) in Iran.58Ian Talley and Benoit Faucon, “Iranian Military-Owned Conglomerate Sets Up Shop in Venezuela,” Wall Street Journal, July 5, 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/iranian-military-owned-conglomerate-sets-up-shop-in-venezuela-11593972015. For the last fourteen years, the MODAFL has partnered with Venezuela’s defense-logistics agency, the Venezuelan Company of Military Industries (CAVIM), setting up opaque military projects and shielding financial transfers through PDVSA’s commercial exchange with China.59Joseph Humire and Ilan Berman, Iran’s Strategic Penetration of Latin America (Washington, DC: Lexington Books, 2014), chapter 7, 63–70.

The dual-use nature of Iran’s cooperation with the Maduro regime, layered with the illicit finance connections of its facilitators and Hezbollah’s established crime-terror network in Venezuela, creates a tier-one national security concern for the United States—one that is multifaceted and requires a robust response.

Policy Recommendations

The United States’ “maximum pressure” policy, in effect since January 2019, has focused on eroding the political and economic support of the Maduro regime. Still, the regime has proven resilient because it relies on external state and non-state actors. Unlike Colombia’s FARC or ELN, Hezbollah is one of the less visible non-state actors helping the Maduro regime, but an important one nonetheless.

Understanding the nature of how Hezbollah operates in Venezuela, through the lens of threat-convergence theory, is critical for US, European, and Latin American efforts focused on finding a solution to the crisis in Venezuela. In order to neutralize the threat, the United States must engage in a counter-threat network approach that equally attacks convergence points throughout the world from which Iran, Hezbollah, and the Maduro regime benefit. However, the international community should combine these targeted actions with a global narrative that delegitimizes Hezbollah’s presence in the region, with the goal of diminishing the terrorist group’s influence in the larger Lebanese communities in Latin America.

Any strategy that aims to diminish Hezbollah’s influence in Latin America must work with the Lebanese diaspora that is as much a victim as it is the target of Hezbollah’s illicit activities. The following actions follow this strategy.

- The United States has been helping to boost regional counterterrorism cooperation in recent years through hemispheric ministerial forums that have led to the first four Hezbollah terror designations in Latin America.60President Mauricio Macri of Argentina was the first Latin American leader to designate Hezbollah as a terrorist organization via decree 489 on July 16, 2019; President Mario Abdo of Paraguay followed suit on August 9, 2019 via decree 2307. Finally, President Ivan Duque of Colombia and President Juan Orlando Hernandez of Honduras also designated Hezbollah as a terrorist organization on January 20, 2020 during the Third Hemispheric Counterterrorism Ministerial Conference in Bogota, Colombia. Under current conditions of COVID-19, the momentum for these forums has stalled, but the importance of the designations remains. The designation of Hezbollah as a terrorist organization is critical to ensuring that each country criminalizes the act of membership or support of Hezbollah, so that local authorities can prevent potential terrorist actions before they take place. Thus, continuing with these Hemispheric Counterterrorism Ministerial Conferences will help to ensure that the regional counterterrorism coalition strengthens.

The hemispheric ministerial forums were essential in building a broader coalition of countries in Latin America that supports these terror designations. Through a total of three forums from December 2018 to January 2020, this effort has grown a coalition of eighteen participating and four observing nations, as well as the participation of the United Nations (UN), the Organization of American States (OAS), the International Criminal Police Organization (INTERPOL), and the Police Community of the Americas (AMERIPOL). Each forum built on the success of the last to establish a regional consensus on the concern of the Hezbollah network’s activities in Latin America, officially declared through a joint communique.61“Joint Communique of the Third Hemispheric Ministerial Conference to Combat Terrorism in Bogota, Colombia,” January 20, 2019, http://www.itamaraty.gov.br/en/press-releases/21235-third-hemispheric-ministerial-conference-to-combat-terrorism-joint-communique. This document helped reinforce existing terror designations of Hezbollah in Latin America and catalyze new countries to consider doing the same.

- A primary conduit of the convergence of organized crime and international terrorism is illicit finance. Financial-intelligence units (FIUs) are the nerve center of a government’s ability to collect, analyze, and report on suspicious activity related to money laundering, corruption, terror finance, and other financial crimes. FIUs have played an outsized role in helping to shut down the illicit financial networks of Hezbollah and its sympathizers worldwide. In the absence of adequate antiterrorism legislation in Latin America, the FIUs have established many mechanisms to cooperate on regional counter-terror-finance efforts. This FIU cooperation in the Americas should be expanded to Gulf states in the Middle East—namely the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Bahrain, Kuwait, and Oman—that oversee well-known money-laundering jurisdictions widely and constantly used by Iran and Hezbollah. United Nations Security Council Resolution 2462 provides an impetus for this cooperation.

- The US State Department (and Commerce Department), in coordination with the Department of Homeland Security International Trade Office, should establish a robust public-diplomacy campaign with Lebanese and other Arab communities throughout Latin America, to build partnerships aimed at weeding out Hezbollah’s malign influence. Such partnerships would need to be multifaceted, with commercial cooperation, cultural exchange, customs enforcement, and media partnerships aimed at anti-corruption initiatives that help legitimate businessmen stay away from the perverse incentives that Hezbollah or any other illicit actors could offer. Many in the broader Lebanese communities in Latin America are eager to participate in efforts that help build credibility to reduce the reputational risk of their commercial activity.

- The Organization of American States could adopt a convergence task force that works on identifying convergence points where Hezbollah and other crime-terror networks operate in Latin America and the Caribbean. This could be part of the OAS Inter-American Network on Counterterrorism, a project created in 2019 and aimed at strengthening cooperation to prevent and address terrorist threats in the Western Hemisphere. The goal of the convergence task force should be to share real-time information on the logistical networks (persons and entities) that help both the Maduro regime and Hezbollah.

The Iran and Hezbollah nexus in Venezuela, first under Chávez and now with Maduro, has been underestimated by the international community for far too long. The findings in this report demonstrate that these connections exist and are mutually beneficial, allowing Hezbollah a safe space to conduct its global crime-terror operations and providing the Maduro regime with increased illicit support from the Middle East. Curtailing the Maduro-Iran-Hezbollah cooperation is a critical step in stemming illicit networks that are helping to sustain the Maduro regime and prolonging the Western Hemisphere’s worst humanitarian crisis.

Image: Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro next to Iranian President Hassan Rouhani during the 18th Summit of Heads of State and Government of the Non-Aligned Movement in Baku, Azerbaijan. Iran-backed Hezbollah operates clandestine networks of clans in Venezuela with financiers, fixers, and facilitators connected to the Maduro regime. Picture taken on October 25, 2019.