How to strike a grand bargain on EU nuclear energy policy

Table of contents

Executive summary

Introduction

The war in Ukraine: A new dimension to the nuclear debate in Europe

What does a peace pact on nuclear energy look like?

Conclusion

Executive summary

Nuclear energy was once a source of European integration beginning with the creation of Euratom, the European Atomic Energy Community, in 1958. However, it has become in the contemporary European Union a source of division, with France and Germany leading rival blocs regarding its future. As a result the EU does not meaningfully fund nuclear energy and member states have engaged in political interference trying to block other member states’ attempts to launch nuclear projects. Nuclear energy is today a source of European disunion. This acrimony has come at a terrible time for the EU, when it urgently needs to decouple from weaponized Russian energy supplies and decarbonize due to the worsening climate emergency. This paper proposes that the EU reduce Russia’s presence in European nuclear markets and sign a “peace pact” allowing each country to pursue its own energy mix without political interference as part of a grand bargain. This bargain would recognize that nuclear energy is a crucial part of Europe’s energy mix, ensure the EU adoptsa technology-neutral approach in the Green Deal Industrial Plan and Net Zero Industrial Act while ramping up support for nuclear skills, research, and development, in exchange for further integration of electricity markets and agreement on its reform, higher renewable targets and renewed work and research on the management of nuclear waste. Only such a peace pact recapturing the spirit of technological optimism and geopolitical commitment behind the launch of Euratom can help Europe overcome the deep nuclear divisions which are holding it back.

Introduction

The history of European nuclear energy: From integrative to divisive force

Once upon a time, nuclear energy united postwar Europe in excitement. About eight kilometers from the center of Brussels, Belgium, sits an eye-catching tourist attraction that garners almost 600,000 visitors per year. The 335-foot tall Atomium, described on the eponymous website as “a monumental structure halfway between sculpture and architecture and where the cube flirts with the sphere,” is a sight to see. Unveiled as the flagship construction for the 1958 Brussels World Fair, the Atomium was meant to represent the faith people put in science—especially nuclear science—and what that could mean for human progress. To this day, the nine glimmering spherical atoms that make up the Atomium are a physical representation that nuclear energy has not always been seen as a source of European division.

Today, political Brussels faces an unprecedented energy puzzle. European policymakers, still grappling with the consequences of the energy crisis caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, have scrambled to reaffirm the continent’s position as a global climate leader. The bloc must adapt to the Russian gas supply shock, all while accelerating an energy transition that provides sufficient and cost-competitive energy in a way that does not transfer Europe’s dependency from Russian gas to Chinese-controlled critical raw materials. At the same time, the US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which provides generous incentives for green industries to localize production in the United States, could threaten the viability of industries in Europe, all while the transatlantic community pushes to move green supply chains away from China. In this context, European policymakers are fiercely deliberating the future of nuclear energy: is it a critical enabler of Europe’s energy transformation, as a stable source of low-carbon energy, or a dangerous blocking point that diverts funding from renewable energy deployment? This has drawn sharp divisions between France and Germany. And in stark contrast to the optimistic days of the Atomium, nuclear energy is now far from being at the center of European integration: when the European Commission first presented the RePowerEU plan in March 2022 with the aim of reducing EU reliance on Russian gas, nuclear power was not even mentioned. It has become a source of European disunion.

France-Germany divide: From pro-nuclear geopolitics to anti-nuclear protests

The Atomium is testament to the fact nuclear energy was not always a toxic subject in Brussels. To understand the nuclear debate in Europe today, one must go back almost seventy years to see how Europe approached energy access and economic integration in parallel with post-WWII reconstruction. Nuclear energy, now the most divisive topic in Europe’s energy transition, was once a central pillar of European integration. That is not to say the path there was clear cut or simple. After World War II, European leaders knew that successful reconstruction would require secure and reliable access to electricity and that overdependence on foreign energy sources could create major problems with reconstruction efforts.1Barnes, Pamela M., and Ian Barnes. The Politics of Nuclear Energy in the European Union: Framing the Discourse: Actors, Positions and Dynamics. 1st ed. Verlag Barbara Budrich, 2018. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvddzswc. This is why the bloc began, essentially, with energy. In 1951, Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and West Germany signed the Treaty of Paris, which created the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), the precursor to the European Economic Community (ECC) and eventually the European Union. The primary role of the ECSC was to develop a common market of coal and steel within Western Europe, ensuring that Western Europe would have guaranteed access to these materials.“2Treaty Establishing the European Coal and Steel Community, ECSC Treaty,” EUR-Lex, updated December 11, 2017, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/EN/legal-content/summary/treaty-establishing-the-european-coal-and-steel-community-ecsc-treaty.html. According to Robert Schuman, one of the fathers of European integration, the point of this common market was to make another war between France and Germany “materially impossible,” as coal and steel were the primary resources required to build armaments at an industrial scale up until the Second World War.“3Schuman Declaration May 1950,” European Union, accessed July 31, 2023, https://european-union.europa.eu/principles-countries-history/history-eu/1945-59/schuman-declaration-may-1950_en.

Looking to further deepen cooperation, the Foreign Ministers of the ECSC states gathered for the Messina Conference in 1955. Among other developments, the ministers agreed upon both the need to further develop the technology for nuclear energy generation and the establishment of a common European institution that would oversee this development. This decision eventually led to the creation of the European Atomic Energy Community—Euratom. The Suez Crisis in 1956 starkly highlighted Europe’s problem with importing most of its energy sources, and the ECSC’s foreign ministers decided to appoint “three wise men”4Louis Armand, chairman of French Railways (SNCF), Franz Etzel, vice-president of the ECSC High Authority, and Francesco Giordani, the former chairman of the Italian National Committee for Nuclear Research (CNRN). to set targets for European nuclear energy. At the height of the Suez Crisis, it was decided that European coal, water, and natural gas would be unlikely to meet more than a third of projected increase in electricity demand: another major argument in favor of nuclear energy.

It was in this spirit that the idea of pan-European nuclear energy efforts really began to gain traction. And finally, in 1958—the year the Atomium opened in Brussels—the six original members of the ECSC signed the Euratom Treaty. The treaty pooled core aspects of the nuclear industries of member states, ensured standards for nuclear safety and security, and promoted cooperation in research and development into nuclear energy. R&D was critical: at the time, American players dominated nuclear technology, which they licensed out to European energy providers. Building out European nuclear capacity was, beyond a project to work together toward the peaceful use of nuclear energy, also seen as an instrument for Europe to eventually achieve energy independence. Nuclear energy was seen as key to European integration—not division.

During this time, a set of narratives predominated in Europe that helped leaders gain support and acceptance from the public to develop nuclear energy capabilities: there were huge reconstruction needs, notably in steel (and correspondingly in coal); a desire for peaceful cooperation with neighbors; a recognition that Europe was still excessively dependent on nonindigenous energy sources, especially oil from the Middle East; concerns that coal would eventually run out; and the threat that high energy prices would pose to economic recovery and growth. This brought the six together into Euratom in a spirit of geopolitical purpose and technological optimism symbolized by the Atomium at the 1958 World’s Fair.

Nuclear power continued to gain traction over the following decade. After France’s failure to maintain control over colonial Algeria, there was a deep desire in Paris to reduce reliance on energy imports from the Arab League. However, it was the 1973 energy crisis that again highlighted Europe’s collective continued vulnerability on foreign sources of energy and propelled Europe into becoming the most nuclearized region in the world. That year, Arab members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) placed an embargo on the United States and allies that supported Israel in the 1973 Yom Kippur War. At the time, Western Europe and Japan relied on OPEC states for between 45 percent and 50 percent of their oil, and when market prices climbed by 300 percent as a result of the embargo, import-dependent countries became acutely aware of their vulnerability.5G. Les Gros, “The Beginning of Nuclear Energy in France: Messmer’s Plan,” Revue Generale Nucleaire 5 (2020): 56-59; and Gregory L. Schneider, The 1973 Oil Crisis and Its Economic Consequences, The Bill of Rights Institute, July 31, 2023, https://billofrightsinstitute.org/essays/the-1973-oil-crisis-and-its-economic-consequences. Could nuclear power potentially reduce those vulnerabilities? Given its longstanding geopolitical concerns—post-Algerian independence in 1962—and concerns about Arab-energy supplies, France led the charge across Europe, via the “Messmer Plan,” to invest in nuclear and to affirm the power source as it is relied upon today.6Author’s note: The Messmer Plan notably entailed the construction of 13 reactors, doubling France’s generation capacity. In fact, plants built or planned immediately following the 1973 oil shock still represent 40 percent of today’s nuclear capacity worldwide.7Peter Fraseret al., Nuclear Power and Secure Energy Transitions, International Energy Agency (IEA), September 2022, 8, https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/016228e1-42bd-4ca7-bad9-a227c4a40b04/NuclearPowerandSecureEnergyTransitions.pdf.

Political suspicions and ambitions shaped this first nuclear age. France has always been the most advanced country in Europe when it comes to nuclear energy. It created the CEA (national atomic agency) in 1945, which had 1 percent of the total government budget by 1955 and dwarfed all other European nuclear energy budgets at the time. This meant seeking technological alliances overseas. Framatome, a French-led nuclear company, was formed in 1958, under President de Gaulle to acquire the license of the US company Westinghouse’s pressurized water reactor designs for use in France. This acute dependence meant France was nervous about US domination of the nuclear energy space and was in favor of deeper European integration from the get-go to counterbalance it. This spirit was summed up by the French National Assembly in 1956 by Louis Armand, one of the “wise men” and first president of Euratom: “Everything moves so fast that if we do not speed things up, we will never catch up. Without Euratom, it’s simple: all European countries will have to turn to the [nuclear] giants,” referring primarily to the United States and Russia. Armand was indeed worried about European states building century-long dependencies on the two superpowers for nuclear material and technology.

However, over the Rhine, there was as much suspicion of France as with the United States. Initially, West Germany lacked nuclear expertise, but had expertise in chemical and other industrial sectors, and wanted to import cheap supplies of enriched uranium from the United States to underpin a reviving and export-led national industry. In short, many in Germany viewed France’s offer of cooperation as a ploy to control this new industry. These differences also played out when trying to negotiate the Euratom Treaty: France wanted a strong dirigiste framework, whereas West Germany’s approach was more business-friendly.

However, these early optimistic narratives surrounding nuclear energy soon flipped. Excitement for secure and reliable nuclear power gave way to disenchantment and concern for the potential immense destruction caused by disaster and improper waste management. Following the 1979 Three Mile Island incident, the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear power plant disaster, and social justice impacts of improper waste management and uranium mining, public perception of nuclear energy quickly deteriorated throughout Europe.8Dean Kyne and Bob Bolin, “Emerging Environmental Justice Issues in Nuclear Power and Radioactive Contamination,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 13, no. 7 (2016): 700, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4962241/. Through public pressure campaigns, governments soon scaled back investment in new reactors. Crucially for the future of Europe’s collective approach to nuclear energy, France’s first nuclear reactor at Fessenheim on the Rhine, the country’s border with Germany, proved a catalyst for the emergence of the anti-nuclear protest movements in that country and a deep sore in relations between both partners, despite it being at the onset a Franco-German project.9Jan-Henrik Meyer, “‘Where Do We Go from Wyhl?’ Transnational Anti-Nuclear Protest Targeting European and International Organizations in the 1970s,” Historische Sozialforschung (HSR) [Historical Social Research] 39, no. 1 (2014): 212-35. These accidents, crises, and protests built up the fault lines between Germany and France on nuclear energy that continue to this day.

These eventually stark differences between Germany and France over their respective nuclear energy policies can be traced to the late 1970s. The rise of the Green Party in Germany became synonymous with the push for environmental protections, and, alongside it, the desire to phase out nuclear energy.10Kerstine Appunn, “Q&A: Why Is Germany Phasing Out Nuclear Power—and Why Now?,” Clean Energy Wire, April 14, 2023, https://www.cleanenergywire.org/news/qa-why-germany-phasing-out-nuclear-power-and-why-now.

This led to very different political contexts in France and Germany by the early twenty-first century. Across the Rhine, the Greens succeeded in their anti-nuclear pressure so dramatically that no new nuclear reactors have been built in the country since 1989. This was just the beginning. Furthermore, following the Fukushima accident in 2011, Angela Merkel’s government (a coalition between the Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union and the Free Democratic Party) introduced the Energiewende policy, which aimed to shut down Germany’s seventeen nuclear power stations by 2022 and phase out coal power by 2038 (now 2030) through aggressive renewable energy expansion, industrial decarbonization, and efficiency targets. France, as a gesture to Germany following the Fukushima disaster, agreed to close the plant in Fessenheim on the Rhine.11Sarah White, “France’s Oldest Nuclear Reactor to Finally Shut Down,” The Guardian, June 28, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/jun/28/frances-oldest-nuclear-reactor-to-finally-shut-down. This is the political environment that led to Germany shutting down its last three nuclear plants in April 2023—despite widespread international criticism given Europe’s energy needs in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

However, it is crucial to understand Europe’s current predicament that Germany’s Energiewende should not be mistaken for leading to uniquely green results. As a result of pushing for denuclearization, Germany and other EU states became increasingly reliant on cheap imported fossil fuels from Russia—especially natural gas. These fundamental differences between France and Germany form the heart of the divided approach that Europe takes to nuclear energy today. What is more important: a nonnuclear approach to energy tomorrow or a decarbonized approach to energy today?

Nuclear energy today: A critical but divisive source of energy for Europe

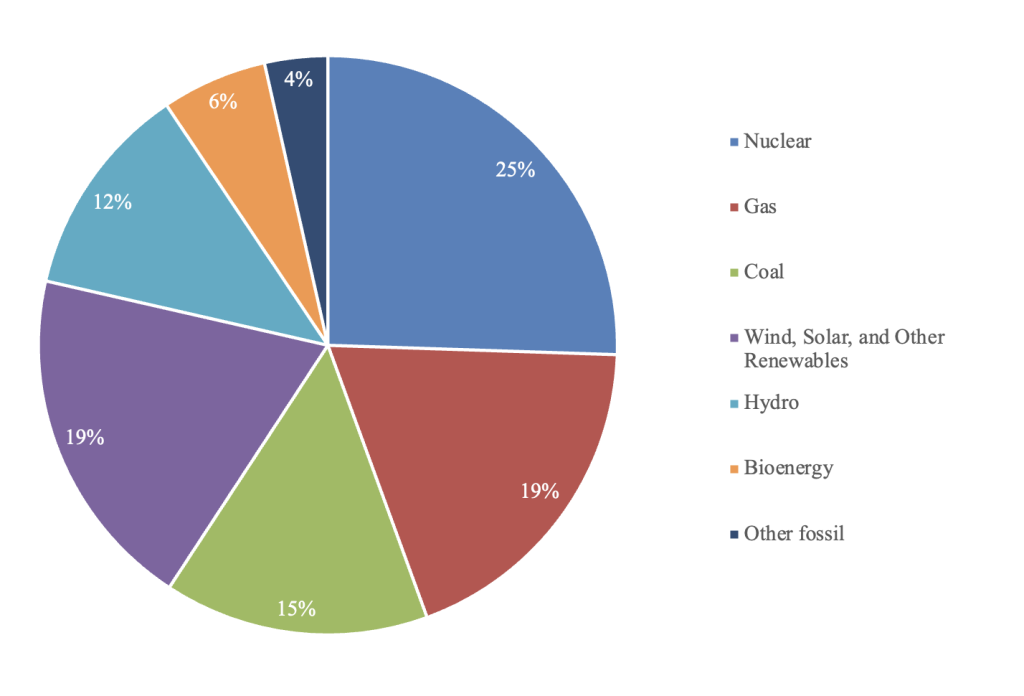

Notwithstanding these political differences, nuclear energy is critically important to Europe. Today, more than one hundred nuclear power plants produce about a quarter of electricity generation in the European Union and nearly half of all carbon-free electricity in the EU.12“Nuclear Power in the European Union,” World Nuclear Association, updated May 2023, https://www.world-nuclear.org/information-library/country-profiles/others/european-union.aspx. Nuclear electricity generation almost perfectly splits the European Union in two. France’s fifty-six reactors (the second largest fleet in the world, behind the United States) produce almost half of Europe’s nuclear electricity. Spain, Sweden, Belgium, and eight other EU countries (Czechia, Finland, Bulgaria, Slovakia, Romania, Hungary, Slovenia, and the Netherlands) make up the rest.

While some member states, such as Belgium, have sharply decreased their nuclear production over the past few years, others have progressively ramped up, as in Romania, whose nuclear power plants came online as recently as 1996, or Hungary, which is expanding its Paks nuclear power plant. At least twenty-five new nuclear reactors are planned in other member states, including six in Poland and two in the Netherlands. Italy, which shut its nuclear reactors down after Chernobyl, making it the only G8 country without its own nuclear power plants up until Germany’s own closures, has now launched a new government initiative to contemplate reintroducing nuclear power.13Federica Pascale, “Italian government begins discussions on clean nuclear power”, Euractiv, 22 September 2023, https://www.euractiv.com/section/politics/news/italian-government-begins-discussions-on-clean-nuclear-power/

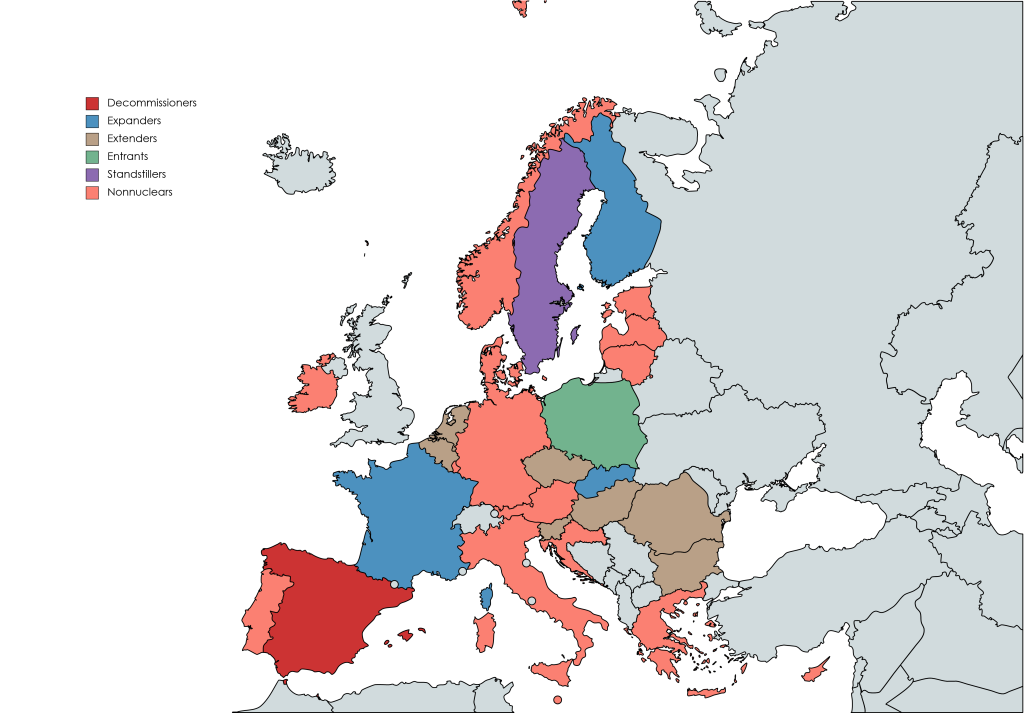

Figure 1. Stances on nuclear energy in the EU

The European Union can therefore be divided into six groups: decommissioners, expanders, extenders, entrants, status-quo players, and nonnuclear energy players. Decommissioners, such as Spain, currently operate reactors but have active plans to phase them out. Expanders, like France and Slovakia, currently have existing power plants and plans to build new ones. Extenders, like Hungary, Slovenia, Bulgaria, Belgium, and the Netherlands, have plans to build new reactors or other measures to extend the operational lifespan of existing reactors. Entrants, like Poland, are countries that have never developed nuclear energy before but wish to do so. Those at a standstill, like Sweden, are countries that have operational power plants but lack official plans to either build more plants and/or units, or decommission existing plants. Finally, nonnuclear members, such as Germany, Denmark, and Austria, are states that have either fully decommissioned or never adopted the use of nuclear energy.14Cécile Maisonneuve and Benjamin Fremaux, European Energy Sovereignty: Putting an End to the Stigma of Nuclear Power, April 11, 2022, Institut Montaigne, https://www.institutmontaigne.org/en/expressions/european-energy-sovereignty-putting-end-stigma-nuclear-power. Prior to Brexit, the United Kingdom and its nine nuclear reactors tipped the political balance in favor of the pro-nuclear camp. With the British exit from the European Union, the pro-nuclear camp lost one critical ally. This sense of flux and indeterminacy has been a driver of such bitter disputes over the EU nuclear future.

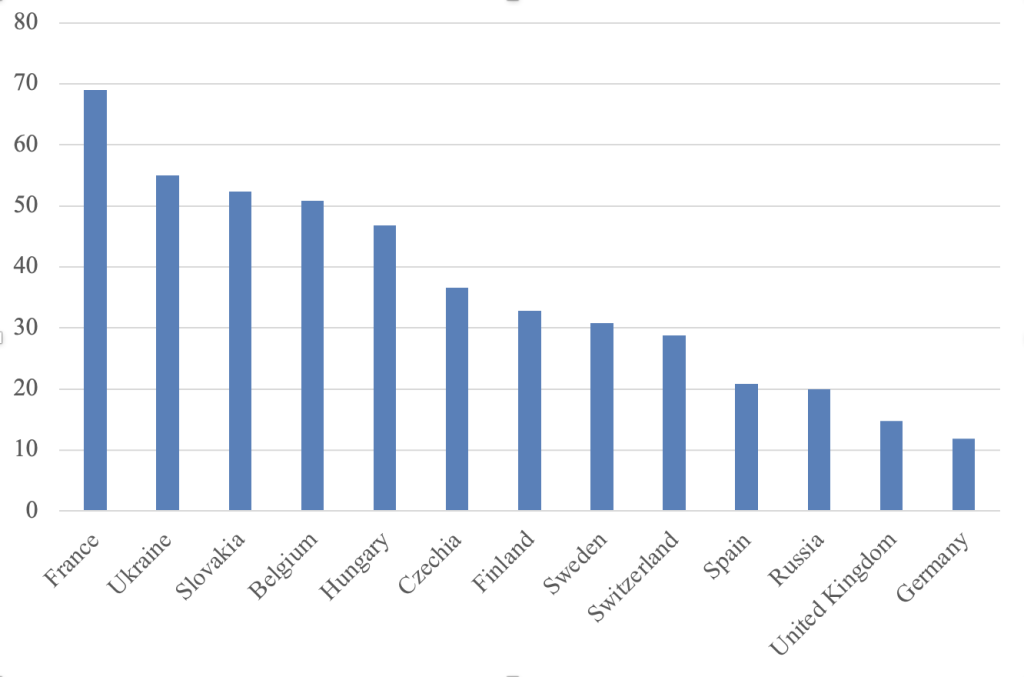

Figure 2. Share of nuclear in domestic electricity production (Europe, 2021)

Not only the question of nuclear power per se but also the question of Russia and the uranium that enables it divides Europeans. To power its nuclear power plants, the EU sources uranium from a limited set of partners, notably Russia, but also Niger, Kazakhstan, Australia and Canada. But the ties between Europe’s nuclear industry and Russia extend beyond uranium. Rosatom, a Russian state-owned nuclear power company, has built reactors in five European countries (Bulgaria, Czechia, Finland, Hungary, and Slovakia), and is currently building two in Slovakia and two in Hungary. What’s more, Rosatom has deep ties with the French nuclear industry, both as a client and as a partner: as late as 2021, EDF (a French state-owned electric utility company) and Rosatom signed a strategic cooperation agreement and a joint declaration on research.15Victor Jack, “French-Russian Nuclear Relations Turn Radioactive,” Politico, April 20, 2023, https://www.politico.eu/article/french-russian-nuclear-relations-radioactive-rosatom-sanctions/. This is not simply a French matter as Germany’s Siemens also remains a partner of Rosatom.16Reuters Staff, “Germany ‘Blocking’ Equipment for Paks Reactors, Hungarian Minister Says,” Reuters, February 14, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/article/hungary-nuclear-siemens/update-1-germany-blocking-equipment-for-paks-reactors-hungarian-minister-says-idINL1N34U1M2. Unsurprisingly, France has come under increasing pressure, especially from Ukraine, to cut ties with Rosatom. As of yet, the European Union has not sanctioned Rosatom or any associated personnel and companies, unlike the United Kingdom and United States.17Max Lin, “US and UK Sanction Dozens of Russia-linked Energy, Shipping Firms,” S&P Global, May 19, 2023, https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/market-insights/latest-news/agriculture/051923-us-and-uk-sanction-dozens-of-russia-linked-energy-shipping-firms. However, the latter still receives imports of Russian uranium.18Ari Natter, “Russia Still Top US Uranium Supplier Despite Efforts to Wean Off,” Bloomberg, June 15, 2023, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-06-15/russia-still-top-us-uranium-supplier-despite-efforts-to-wean-off. In fact, Ukraine wants every European country with ties to Russia’s nuclear industry to cut them. The pressure seems to be working: efforts are underway in various European capitals to wean European nuclear industries from Russian dependence: Poland, Slovakia, and Bulgaria have all recently signed agreements with Western players (notably Westinghouse and EDF).

Uranium imports free of Kremlin-influence pose a challenge for all Western countries. Meanwhile, France in particular has concerns given the recent coup d’état in Niger, which may lead to the state falling under Russian influence; as of 2020, 34.7 percent of French uranium imports came from the country. This is alongside 28.9 percent from Kazakhstan and 26.4 percent from Uzbekistan, two other states where Russia has limited influence.19Marie Thimonnier, “L’uranium importé en Europe et en France provient-il ‘très largement’ de Russie comme l’affirme Yannick Jadot? [Does the Uranium Imported into Europe and France come ‘Very Largely’ from Russia, as Yannick Jadot Claims?],” La Libération, July 5, 2022, https://www.liberation.fr/checknews/luranium-importe-en-europe-et-en-france-provient-il-tres-largement-de-russie-comme-laffirme-yannick-jadot-20220705_LIIEMU2QIRFKZMB46IPBWKFJZQ/. The United States, meanwhile, imported 35 percent of its uranium from Kazakhstan and 15 percent from Russia directly as of 2021.20“Nuclear Explained: Where Our Uranium Comes From,” US Energy Information Administration (website), July 7, 2022, https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/nuclear/where-our-uranium-comes-from.php. This is a collective problem for Western allies, though not an unsolvable one, should the situation degrade, given the extensive uranium deposits in allies such as Australia and Canada. So far, uranium, unlike oil and gas, has not been weaponized by Russia. Again, European countries are divided on what is more important: decoupling from Russian resources totally, as the first priority, or only decoupling from weaponized Russian hydrocarbons.

Nuclear as part of the Green Energy Transition

Many of Europe’s green politicians may suggest otherwise, but any fair analysis of the continent’s energy situation and trajectory shows that Europe will not be able to achieve its net-zero goals without nuclear energy being part of the mix. Long before the urgency injected by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, it was already evident that nuclear energy in Europe is critical when it comes to providing the three-pronged benefits of energy security, sovereignty, and a reduction in emissions as part of a wider net-zero strategy. With EU member states now needing to find alternate energy sources even faster, nuclear energy will have to continue to play a critical role, albeit one that might look very different than in the past.

Nuclear energy is critical to decarbonization

- Europe cannot achieve its existing emissions targets without a partial diversification toward expanded use of nuclear energy. Nuclear energy should be seen as complementary with renewable energy toward lowering carbon emissions.

- EU members are not on track to cut 55 percent of 1990s carbon-emission levels by 2030, as envisioned by the European Green Deal.

- Multiple EU members, especially in Eastern Europe, remain reliant on coal, are landlocked and cannot benefit directly from offshore wind, and lack solar resources.

- Nuclear energy can help address supply shortages and assist with grid stability in a renewables era. Battery storage and demand management can offset short-term energy supply shortages but alternative solutions are needed for long-term seasonal shortages in wind and light.

- Nuclear energy generation, when paired with renewables, brings down the costs of the transition, notably in terms of infrastructure.

There is further potential regarding the adoption of small modular reactors (SMRs).

Nuclear energy as a key enabler of Europe’s decarbonization goals

Nuclear energy is crucial in helping to meet ambitious emissions targets that are likely out of reach at the current pace of transition.21“Low-emissions Sources Are Set to Cover Almost All the Growth in Global Electricity Demand in the Next Three Years,” IEA, February 8, 2023, https://www.iea.org/news/low-emissions-sources-are-set-to-cover-almost-all-the-growth-in-global-electricity-demand-in-the-next-three-years. This is especially true in Eastern Europe, which is still overly reliant on coal, and lacks coastlines for offshore wind and appropriate solar resources.22Kira Taylor, “Poland’s Power Grid Needs €25 Billion Upgrade for Renewables: Report,” Euractiv, October 27, 2022, https://www.euractiv.com/section/electricity/news/polands-power-grid-needs-e25-billion-upgrade-for-renewables-report/. Nuclear reactors already provide about half of the low-carbon electricity generation in the EU, and the countries with the lowest carbon intensity of total electricity production in 2021—Sweden and France—achieved this by utilizing both nuclear and renewable energy production.23“Is the European Union on Track to Meet its REPowerEU Goals?,” IEA, December 2022, https://www.iea.org/reports/is-the-european-union-on-track-to-meet-its-repowereu-goals; “Nuclear Power in the European Union,” World Nuclear Association; and “Greenhouse Gas Emission Intensity of Electricity Generation in Europe,” European Environment Agency, June 2, 2023, https://www.eea.europa.eu/ims/greenhouse-gas-emission-intensity-of-1.

Beyond the low-carbon electricity that nuclear technology already provides, this energy source can accompany and enable the deployment of renewable energy. Rather than being seen as antagonistic, the two should be seen as complementary. The ability of nuclear energy to supply secure and reliable low-carbon power—that can be ramped up and down to meet needs—at a competitive price provides solutions to a suite of shortcomings that result from large-scale renewable energy deployment.

Renewable energy generation is uncertain across hours, days, and seasons and balancing supply and demand becomes increasingly difficult as the grid is characterized by a larger share of renewables. Solutions like battery storage and demand management can help grid operators balance supply and demand across hours or days, but variation across weeks or months requires different solutions. For example, multiweek periods of almost no wind and limited solar power can occur in the winter in Germany—stretches of time that are nicknamed Dunkelflaute, or dark doldrums.24“It Is Harder for New Electric Grids to Balance Supply and Demand,” Economist, April 5, 2023, https://www.economist.com/technology-quarterly/2023/04/05/it-is-harder-for-new-electric-grids-to-balance-supply-and-demand. The lull in generation is currently met by burning fossil fuels, but meeting gaps like these in Germany or elsewhere with nuclear power would be emissions-free. Nuclear energy is already seen as a “baseload” supply (the minimum amount of electricity needed to meet the constant and essential demand) that can be relied upon in the face of variable generation, and is largely used for this purpose.25“Nuclear Power in the European Union,” World Nuclear Association, May, 2023. https://www.world-nuclear.org/information-library/country-profiles/others/european-union.aspx.

Nuclear energy can also help maintain grid stability, a service that can be even more valuable than power generation. Healthy electric grids must balance supply and demand, but also maintain safe frequency to avoid failures or accidents. This becomes more complex with renewable energy generation, in which renewables utilize inverters instead of turbines to convert energy into electricity; turbines maintain frequency free of charge.26“The Physics of Rotating Masses Can No Longer Define the Electric Grid,” Economist, April 5, 2023, https://www.economist.com/technology-quarterly/2023/04/05/the-physics-of-rotating-masses-can-no-longer-define-the-electric-grid. Nuclear electricity utilizes turbines and can thus deliver “ancillary services,” (balance frequency) across a renewable-dominant grid. For example, an analysis of a carbon neutral power system in China projected that in 2060, nuclear energy would supply only 10 percent of total electricity production, but almost half of the ancillary services.27Fraser et al., Nuclear Power and Secure Energy Transitions, 10.

Finally, an effective energy transition may simply be unrealistic without nuclear energy. The International Energy Agency (IEA) projects that the EU will fall short of its ambitious renewable energy targets, and recent research makes it clear that the coal phaseout is not happening fast enough.28“Is the European Union on Track,” IEA; Vadim Vinichenko et al., and “Phasing Out Coal for 2°C Target Requires Worldwide Replication of Most Ambitious National Plans Despite Security and Fairness Concerns,” Environmental Research Letters 18, no. 1, January 11, 2023, https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/acadf6. In Austria, an outspoken nuclear opponent in the European Union, a recent internal government report highlights that the country is not currently on track to reach its climate targets.29Chiara Swaton, “Austria Will Miss Climate Targets despite Green Government Involvement,” Euractiv, April 26, 2023, https://www.euractiv.com/section/politics/news/austria-will-miss-climate-targets-despite-green-government-involvement/. Additionally, the 2022 energy crisis has caused Germany, Poland, and a handful of other European countries to consider delaying plans for coal phaseouts.

It’s worth digging a bit deeper into Germany specifically: combined with gas shortages, the decision to follow through with its plans to phaseout nuclear power has actually increased reliance on coal and other fossil fuels in the short term.30Frank Jordans, “Over and Out: Germany Switches Off Its Last Nuclear Plants,” AP News, April 15, 2023, https://apnews.com/article/germany-nuclear-power-plants-shut-energy-376dfaa223f88fedff138b9a63a6f0da. Unsurprisingly, the decision to follow through with these phaseout plans has drawn increasing controversy and shows that the Greens’ vision for the energy future may no longer be a shared one.31Benjamin Wehrmann, “Nuclear Controversy Flares Up as Germany Shuts Down Last Reactors,” Clean Energy Wire, April 14, 2023, https://www.cleanenergywire.org/news/nuclear-controversy-flares-germany-shuts-down-last-reactors. A recent survey by YouGov in Germany revealed that only 26 percent of Germans fully support a complete phaseout of nuclear power today, with clear divisions across political and regional lines.32“Has Germany’s Era Of Nuclear Energy Come To An End?”, Yahoo Finance, April 18, 2023. https://finance.yahoo.com/news/germany-era-nuclear-energy-come-220000927.html. In Bavaria, Minister-President Marcus Söder recently appealed to keep regional nuclear plants on despite the federal phaseout plans.33Julia Dahm, “Bavaria Wants to Keep Nuclear Plants Running despite Federal Phase-out Plans, Euractiv, April 17, 2023, https://www.euractiv.com/section/politics/news/bavaria-wants-to-keep-nuclear-plants-running-despite-federal-phase-out-plans. His pleas were ultimately rejected—despite the clear climatic and security benefits of keeping the plants running.

A cost-competitive solution to the energy transition

Economic necessity means nuclear energy is not something that Europe can continue to remain divided over. Simply put, including nuclear power in the EU energy supply will bring down the costs of the green energy transition. It will continue to be the least costly low-carbon technology that is dispatchable (meaning readily adjustable to meet fluctuating demand) after hydropower through at least 2025, according to the IEA.34Fraser et al., Nuclear Power and Secure Energy Transitions, 7; and “Low-emissions Sources,” IEA. Achieving net-zero targets globally without investing in nuclear energy would require $500 billion more investment and raise consumer electricity bills on average by $20 billion a year by 2050, the IEA found.35Authors’ note: The IEA’s low-nuclear case includes no new nuclear projects in advanced economies, and nuclear construction kept at a historical average in emerging economies.

That storyline exists within France. RTE’s landmark study, Energy Pathways to 2050, found that the most cost-effective pathways to a carbon-neutral French grid by 2050 require both extending existing reactor life and investing in new reactors alongside renewable energy development.36“Energy Pathways 2050—Key Results of the Study,” RTE, June 24, 2022, https://www.rte-france.com/en/home. Crucially, the IEA has found that the ability to invest in and extend nuclear reactor life well past initial lifetimes, or long-term operation (LTO), is even competitive with renewable energy generation, which now enjoys famously low costs.37“Projected Costs of Generating Electricity 2020,” IEA, December 2020, https://www.iea.org/reports/projected-costs-of-generating-electricity-2020. Ambitious targets for emissions reduction in 2030 and carbon-neutral electricity generation in 2050 may already be unrealistic.38Lars Nitter Havro, “Explainer: Examining Options for the EU as It Competes for Clean Tech Sovereignty,” Rystad Energy, February 5, 2023, https://www.rystadenergy.com/news/explainer-examining-options-for-the-eu-as-it-competes-for-clean-tech-sovereignty. Phasing out nuclear and meeting those targets will be prohibitively expensive, if not impossible, in nuclear-dependent member states. The evidence is clear: there is no path to net-zero for the European Union without a prominent role for nuclear energy.

Advanced reactor designs show potential for new applications

Given the push to renewable sources of energy and the benefits nuclear power plants provide, nuclear energy is likely to be an important component of the net-zero transitions in Europe and abroad. But nuclear in the net-zero age could look somewhat different from the late twentieth century. This gives reason to think that its politics—characterized by division—can change too.

While some countries are hesitant to invest in conventional large-scale reactors for the transition, they are enthusiastic about the potential of advanced reactor designs to enable decarbonization. Belgium and Italy have joined the pro-nuclear alliance as observers due to their intent to only pursue advanced reactor designs, and the Netherlands’ new climate budget pushes for the construction of smaller nuclear reactors.39Paul Messad, “Nuclear vs Renewables: Two Camps Clash in Brussels,” Euractiv, March 29, 2023, https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy-environment/news/nuclear-vs-renewables-two-camps-clash-in-brussels/; and Benedikt Stöckl, “Dutch Government to Invest €28 Billion into New Climate Package,” Euractiv, April 27, 2023, https://www.euractiv.com/section/politics/news/dutch-government-to-invest-e28-billion-into-new-climate-package/.

There are, however, reasons for skepticism. This is not an approach shared by all: Poland, for instance, currently plans to build large reactors, while other countries (e.g., Romania) are refurbishing and investing in existing reactors. Further, countries that are investing in large-scale nuclear, including France and the United States, have made sure to earmark funds for advanced reactor designs, such as evolutions of existing designs of small modular reactors (SMRs).40Liz Alderman, “France Announces a Big Buildup of Its Nuclear Power Program,” New York Times, February 10, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/10/world/europe/france-macron-nuclear-power.html.

Despite the many benefits of such SMRs, they have not yet been commercialized to replace large reactors in the power mix. For one, designs are in various stages of development and license applications, and commercial viability remains uncertain. And while they address cost concerns, commercial SMRs as conceived of today might, according to one study, end up producing twofold to thirtyfold more waste than conventional atomic power plants in operation.41Mark Schwartz, “Stanford-led Research Finds Small Modular Reactors Will Exacerbate Challenges of Highly Radioactive Nuclear Waste,” Stanford University News, May 30, 2022, https://news.stanford.edu/2022/05/30/small-modular-reactors-produce-high-levels-nuclear-waste/. Additionally, existing infrastructure and regulation has been designed for large reactors and adapting for SMRs will require grid investments and policy changes.

Overall, SMRs and advanced reactor designs have potential and require additional research and development. Investment should continue to address shortcomings, and designers/policymakers should think critically about how to take advantage of the benefits of nuclear power in the decarbonized energy mix. We should expect such reactors to play a different but important role in the energy transition, as there will be specific applications where the use case for large reactors is less clear. This might be the case for industrial sectors with hard-to-abate emissions, including hydrogen production, mineral extraction necessary for the clean transition, and other industrial processes. These reactors will not, however, replace the need for large-scale reactors—and they won’t short-circuit the politics and long-standing opposition to nuclear power.

The war in Ukraine: A new dimension to the nuclear debate in Europe

Nuclear has divided Europe at a time when unity is required

Just as in the crises of 1956 and 1973, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 once again exposed Europe’s heavy reliance on imported fossil fuel supplies. It also forced policymakers to reassess their understanding of both energy security and energy independence. In the span of a decade, Europe witnessed Libya, a key oil supplier to its south, engulfed in a devastating civil war, and more recently, Russia, once perceived as a reliable gas supplier to the East, invading Ukraine and shutting down gas supplies. Whereas the nuclear-versus-renewables debate hinged on its environmental impacts, the war in Europe has placed energy sovereignty as the number one priority, shifting the terms of the debate.

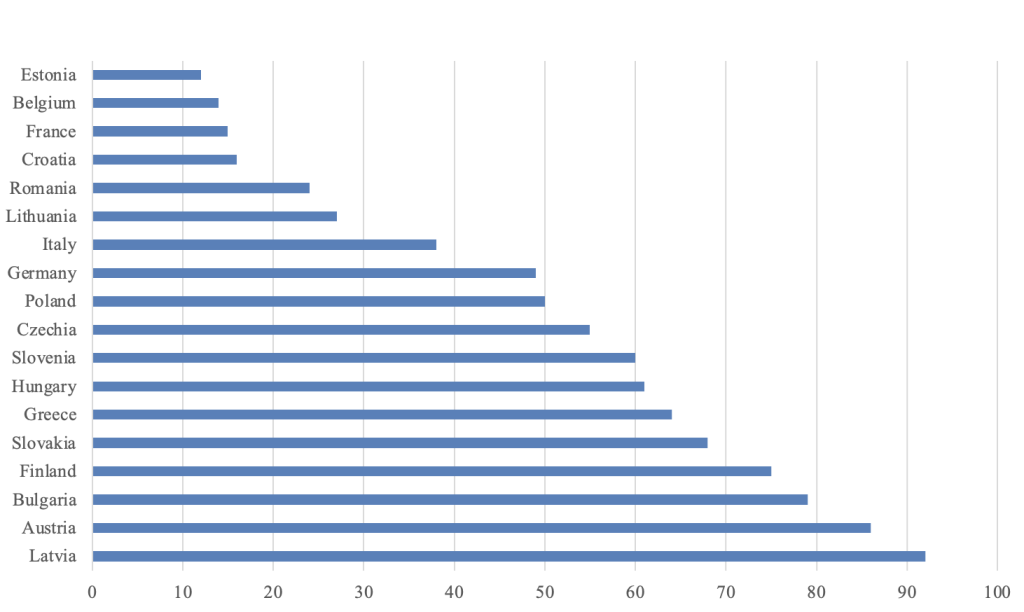

Figure 3. Share of gas supply from Russia in Europe (2021)

For member states that first invested in nuclear energy to provide energy security, the war in Ukraine has validated the need to invest in a new age of nuclear energy. Proponents argue that nuclear power has clear benefits to deliver security and independence, along with the decarbonization benefits described above. Nuclear energy can provide locally produced electricity and heat, with relatively few inputs, anywhere in Europe.44“Nuclear Process Heat for Industry,” World Nuclear Association, updated September 2021, https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/non-power-nuclear-applications/industry/nuclear-process-heat-for-industry.aspx. Nuclear fuel is extremely energy dense—one uranium pellet, which is around one inch tall, is equivalent to one ton of coal or 120 gallons of oil.45“3 Reasons Why Nuclear Is Clean and Sustainable,” US Office of Nuclear Energy, March 31, 2021, https://www.energy.gov/ne/articles/3-reasons-why-nuclear-clean-and-sustainable. As a result, reactors have a relatively small geographic footprint and waste is minimal relative to power output. Uranium—the most common fuel used for nuclear power—is abundant and geographically diverse, even though Russia remains one of Europe’s largest suppliers of enriched uranium.46“Supply of Uranium,” World Nuclear Association, updated May 2023, https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/nuclear-fuel-cycle/uranium-resources/supply-of-uranium.aspx; and Dyfed Loesche, “Where the Uranium Comes From,” Statista, December 15, 2017, https://www.statista.com/chart/12304/countries-with-the-biggest-production-volume-of-uranium/. Operating costs remain low once reactors are built and the levelized costs of energy (LCOE) are consistently lower than fossil fuel alternatives—especially where supply is scarce.47“Economics of Nuclear Power,” World Nuclear Association, updated August 2022, https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/economic-aspects/economics-of-nuclear-power.aspx; and “Projected Costs,” IEA.

Instead of a joint European approach, a new division has embedded itself between pro- and anti- nuclear camps: the question becomes, does Europe leave nuclear behind and seek other options for secure, low-carbon dispatchable energy, or reinvest in established and new nuclear technologies and fully recognize the role they can play in the green energy transition?

Figure 4. EU electricity generation by fuel (2021)

Europe’s politics surrounding nuclear energy are now so acrimonious that there was no mention of nuclear energy in the bloc’s RePowerEU plan to decouple from Russian energy sources, as previously mentioned. Germany has also been engaging in political interference to block other member states from developing nuclear energy. In February 2022, Germany’s energy minister, Steffi Lemke, of the Green Party, visited Poland and claimed that Germany would use “the appropriate legal instruments at the European level” to prevent Poland from launching a nuclear program.48Daniel Tilles, “Germany to Use “Legal Instruments” in Response to Poland’s Nuclear Power Plants”, Notes from Poland, February 23, 2023. “https://notesfrompoland.com/2022/02/23/germany-to-use-legal-instruments-in-response-to-polands-nuclear-power-plans/ Political acrimony between France and Germany over Berlin’s refusal to allow meaningful EU funds to be allowed to support nuclear energy has led to a suspicion in the French cabinet that Germany’s policy may not in fact be ideological but commercial, with a desire to undercut a French energy advantage.49Interview with a French senior official, March 20, 2023.

Divisions have calcified. At a meeting in Stockholm in February 2023, eleven member states agreed to deepen cooperation on nuclear energy. This pro-nuclear alliance, with France at its helm, includes Bulgaria, Croatia, Czechia, Finland, Hungary, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia, with Belgium and Italy joining as observers. At the core, these member states envision the electricity source as central to the energy transition and want it placed “on an equal footing” with renewables as a low-carbon source of energy. In October, they submitted a proposal to the European Commission to ensure plans for electricity market reforms do no harm to their existing nuclear fleet. 50John Ainger, “France Pitches Plan to End EU Nuclear-Energy Deadlock With Germany”, Bloomberg, 3 October 2023, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-10-03/france-pitches-plan-to-end-nuclear-energy-deadlock-with-germany?srnd=premium-europe&sref=SamVlrGx&embedded-checkout=true On the other side of the table, a group dubbed the Friends of Renewables was formed in response to oppose measures to accommodate nuclear power and is “ready to fight” against future concessions. Austria has formed the opposition with Estonia, Spain, Denmark, Ireland, Luxembourg, Portugal, Latvia, Lithuania, and Germany.51“Onze Etats membres de l’Union européenne appellent à un renforcement de la coopération européenne en matière d’énergie nucléaire [Eleven EU Member States Call for Enhanced European Cooperation on Nuclear Energy],” French Ministry of Ecological Transition and Territorial Cohesion, and Ministry of Energy Transition, February 28, 2023, https://www.ecologie.gouv.fr/onze-etats-membres-lunion-europeenne-appellent-renforcement-cooperation-europeenne-en-matiere; Kate Abnett, “France Seeks Pro-nuclear Alliance for EU Energy Talks,” Reuters, February 27, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/france-seeks-pro-nuclear-alliance-eu-energy-talks-2023-02-27/; and Messad, “Nuclear vs Renewables.”

The formation of these two blocs impedes consensus building in Europe on crucial energy policy initiatives now and in the future. The two increasingly entrenched sides lobby hard to gain allies for their cause, and the consequences of this extend beyond the legislatives efforts themselves. The nuclear debate has, in the words of an attendee of the Atlantic Council’s decarbonization Paris policy workshop in March, escalated the energy crisis into “a political crisis, a crisis of trust” that has “wasted political capital” and threatens the conventional consensus-building process for EU energy policy“52Decarbonization Solutions for Addressing Europe’s Green Industrial Policy Challenge,” Event Recap, Transform Europe Initiative, Atlantic Council, April 18, 2023, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/commentary/event-recap/decarbonization-solutions-for-addressing-europes-green-industrial-policy-challenge-2/. In this vein, the French National Assembly recently published a report on “the loss of French sovereignty in energy,”53“Commission d’enquête visant à établir les raisons de la perte de souveraineté et d’indépendance énergétique de la France [Commission of Inquiry to Establish the Reasons for the Loss of Sovereignty and Energy Independence of France],” National Assembly of France, October 11, 2022, https://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/dyn/16/organes/autres-commissions/commissions-enquete/ce-independance-energetique. pointing to European energy rules and its impacts on the French nuclear industry over the past twenty years as the main culprit. Nuclear energy has become—at the worst possible time—a source of European disunion.

Making matters worse is the poor state of the French nuclear industry. The French Senate recently published a report on French nuclear energy, noting that, “due to a lack of coherent policy and investment this energy is in structural decline.”54Daniel Gremillet, Jean-Pierre Moga, and Jean-Jaques Michau, “Nucléaire et hydrogène: l’urgence d’agir [Nuclear and Hydrogen: The Urgency to Act,” Rapport d’information n° 801, Senate of France, July 20, 2022, https://www.senat.fr/rap/r21-801/r21-8010.html. By late 2022, a record twenty-six of its fifty-six reactors were offline for maintenance or repairs after the worrying discovery of cracks and corrosion in some pipes used to cool reactor cores.55Liz Alderman, “Half of France’s Nuclear Plants Are Off-Line,” New York Times, November 15, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/15/business/nuclear-power-france.html. This crisis sent French nuclear generation to a thirty year low turning the country into a net energy importer for 2022, importing even from Germany. Lack of skills and capacity domestically meant France was required to bring in American and Canadian experts and contractors. This is part of a series of deep problems that have faced EDF, which the French government fully nationalized in 2022. Therefore, despite strategic and climatic vitality, European nuclear power faces a double bind: that of supranational German-led political opposition and French-led domestic underperformance. To truly unlock nuclear energy’s potential, both will have to eventually be overcome at the EU level: removing German hostility to countries wishing to develop their own industries and providing support to overcome French failures.

Nuclear divisions hinder Europe’s efforts to build a truly climate-neutral economy

This row is impacting core EU policymaking. The nuclear debate inevitably emerges in every energy-related discussion in Brussels, including the negotiations for the Renewable Energy Directive and related emissions reductions targets, discussions around standards for hydrogen production, decisions surrounding funding guidelines for that production, and plans for electricity market reforms. Ongoing clashes between EU member states therefore significantly delay agreements at a time when Europe needs to present a unified agenda and accelerate its efforts if it is to meet its climate neutrality goals. The worse the Franco-German “motor,” the worse the functioning of the EU.

Disagreements on nuclear energy also bog down efforts to invest in the infrastructure required for a net-zero European economy. France, Spain, and Germany are unable to find consensus on how to allocate EU financial resources toward the integration of European energy infrastructure like hydrogen pipelines. This dispute has already had political consequences, such as when President Emmanuel Macron threatened to delay the construction of BarMar, a hydrogen pipeline that would run from Spain through France to Germany.

The nuclear dispute also impacts Europe’s green industrial strategy. Ambiguous language in the recent Net Zero Industry Act (NZIA) proposal from the Commission is aimed more at quieting both factions than bridging the gaps between them.56“Net-Zero Industry Act: Making the EU the Home of Clean Technologies Manufacturing and Green Jobs,” European Commission, March 16, 2023, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_23_1665. The NZIA, the bloc’s response to the US IRA, is part of the EU’s broader Green Industrial Plan, which European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen declared is meant to “to scale up manufacturing of clean technologies in the EU and make sure the Union is well-equipped for the clean-energy transition.”57“The Green Industrial Plan,” European Commission, February 1, 2023, https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal/green-deal-industrial-plan_en. It defines which net-zero technologies are strategic for both Europe’s industry and decarbonization, which, in turn, determines which technologies will get access to a wide range of benefits, potentially including fast-tracked permitting, simplified regulatory oversight, and European funding. The main body of the act includes “advanced technologies to produce energy from nuclear processes with minimal waste from the fuel cycle” and “small modular reactors” as two of the technologies that will benefit from the policy initiatives—but this excludes the current reactors essential to Europe’s energy mix and technologies such as the second-generation pressurized water reactors that France plans to develop.58Paul Messad, “EU’s Net-Zero Industry Act Sends ‘Positive Signal’ for Nuclear, Advocates Say,” Euractiv, March 17, 2023, https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy-environment/news/eus-net-zero-industry-act-sends-positive-signal-for-nuclear-advocates-say/.

Additionally, the annex to the policy defining those technologies, which “will receive particular support” and are subject to the “40 percent domestic production benchmark,” does not mention any type of nuclear technology, nor does a separate document identifying investment needs and funding availability.59Messad, “EU’s Net-Zero Industry”; and “ANNEXES to the Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on Establishing a Framework of Measures for Strengthening Europe’s Net-zero Technology Products Manufacturing Ecosystem (Net Zero Industry Act),” European Commission, March 16, 2023, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:6448c360-c4dd-11ed-a05c-01aa75ed71a1.0001.02/DOC_2&format=PDF. President von der Leyen has said that “nuclear can play a role in our decarbonization effort,” but is not deemed “strategic for the future.”60Frédéric Simon, “Von der Leyen: Nuclear not ‘Strategic’ for EU Decarbonisation,” Euractiv, March 24, 2023, https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy-environment/news/von-der-leyen-nuclear-not-strategic-for-eu-decarbonisation/. Similarly, the Commission working paper on “strategic” green industries does not once mention nuclear power.61“Commission Staff Working Document: Investment Needs Assessment and Funding Availabilities to Strengthen EU’s Net-Zero Technology Manufacturing Capacity,” European Commission, March 23, 2023, https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2023-03/SWD_2023_68_F1_STAFF_WORKING_PAPER_EN_V4_P1_2629849.PDF.

The European Union does not meaningfully fund nuclear energy

The EU does not meaningfully fund nuclear energy despite its strategic and climatic importance and core importance to multiple member states. While there are already funding initiatives for nuclear energy in the EU, the majority of these relatively small resources are set aside for safety and decommissioning programs aimed at “improving the safety standards of nuclear power stations and ensuring that nuclear waste is safely handled and disposed of,” while leaving it up to member states to “choose whether to include nuclear power in their energy mix.”62Corinne Cordina, “Nuclear Energy,” European Parliament: Fact Sheets of the European Union, April 2023, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/factsheets/en/sheet/62/nuclear-energy. This leaves a gap in the securing of resources needed for nuclear fuel (primarily uranium), as well as deficits in vital investments in technical skills training for the development and operation of nuclear energy equipment and encouraging technological innovation in the field.

The current energy crisis, political disputes, and the new wave of industrial economic initiatives further prove that this approach needs updating. For perspective, the €132 million package announced in March that directs funding from Horizon Europe (see Table 1) for research in small modular reactors is a drop in the ocean compared to recent measures in the United States.63Directorate-General for Research and Innovation, “Researchers to Receive €132 million through the new Euratom Research and Training Work Programme 2023-2025 for Investments in Nuclear Innovation and Technology,” European Commission, March 17, 2023, https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/news/all-research-and-innovation-news/researchers-receive-eu132-million-through-new-euratom-research-and-training-work-programme-2023-2025-2023-03-17_en. The $6.85 billion in direct funding and additional generous US tax credits are clearly aimed at continuing and enhancing the domestic nuclear industry through support to existing reactors, supply chain enhancement, and technology-agnostic funding for research and development. There is a clear opportunity to reframe the NZIA and additional EU policy initiatives in a way that finds a reasonable middle ground for nuclear energy’s role in the transition.

Nuclear disputes stand in the way of deepening European electricity markets via infrastructure and reform

There is a further issue holding back Europe. The EU is already the world’s largest interconnected electricity market, ensuring that power flows from where it is produced to where it is needed. But the energy crisis and the challenges posed by increasing shares of renewables calls for more integration, an objective that Europe has so far failed to meet. In January 2023, the European Court of Auditor released a report pointing to the lack of progress made in recent years, notably on interconnectors.64Special Report 03/2023: Internal electricity market integration, European Court of Auditors, March 2023, https://www.eca.europa.eu/en/publications?did=63214. In 2002, the European Council had set a target of 10 percent of electricity interconnection as a proportion of generation capacity for each member state. The target has yet to be reached, three years past the 2020 deadline.

France’s geography places it at the heart of European energy systems—between Northern wind and southern sunshine. And yet, French policymakers have been slow to build out interconnectors, to the dismay of their Spanish neighbor.65“France, Spain to Ease Pyrenees Power Bottleneck,” Reuters, February 14, 2015, https://www.reuters.com/article/france-spain-electricity-idUSL6N0VG3V020150213. The last high voltage interconnector to come online across the Pyrenees was in 2015, despite the rapid deployment of renewable generation capacity in Spain.66“Grid Bottlenecks Could Derail Europe’s Renewable Energy Boom”, Rystad Energy, December 2022, oilprice.com/Alternative-Energy/Renewable-Energy/Grid-Bottlenecks-Could-Derail-Europes-Renewable-Energy-Boom.html. More recently, the BarMar spat was the latest iteration of French obstruction.

Many factors could explain France’s reluctance to become a European energy platform: the pressure it would place on France’s domestic grid,67Sam Morgan, “View from Brussels: The Curious Case of the Channel Cable”, E&T, February 8, 2023, https://eandt.theiet.org/content/articles/2023/02/view-from-brussels-the-curious-case-of-the-channel-cable/. or shielding its nuclear electricity exports to Germany and Italy from Spanish competition.68Xavier Grau del Cerro, “Why is France not Interested in the Midcat Pipeline?”, Ara, August 19, 2022, https://en.ara.cat/business/why-is-france-not-interested-in-midcat_1_4465828.html But France also heavily subsidizes its nuclear industry, making French nuclear electricity historically among the cheapest sources of energy across the EU.69Eurostat, Electricity Prices for Household Consumers, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/nrg_pc_204/default/table?lang=en These subsidies led EDF to the brink of default and subsequent nationalization by the French government last year.70Sarah White, “EDF Warns of €26bn Hit from Output Curbs and Energy Price Caps”, Financial Times, March 14, 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/58e31e69-3089-4383-a49e-87d96dd2f233. In this context, this reason explains French policymakers’ reluctance to build out more connections: France cannot afford to subsidize nuclear-derived electricity for Europe at large. This is how France and not only Germany contributes to the blockage at the heart of European nuclear energy politics.

No wonder then, that Europeans have struggled to agree on electricity market reforms this year. In March 2023, the European Commission proposed various revisions to regulations governing Europe’s electricity market design. While leaving market fundamentals unchanged, the Commission’s proposals included consumer protection measures, supporting long-term power purchase agreements and, more controversially, two way contracts for differences (CfDs), whereby governments top up energy producers when prices drop below a minimum threshold, and vice versa when a maximum threshold is reached.71European Commission, “Electricity Market Design revision: Proposal to amend the Electricity Market Design rules”, https://energy.ec.europa.eu/publications/electricity-market-reform-consumers-and-annex_en.

This last point sparked intense debate between the pro and anti-nuclear camps.72Kira Taylor, “EU countries fail to agree position on electricity market reform”, Euractiv, June 20, 2023, https://www.euractiv.com/section/electricity/news/eu-countries-fail-to-agree-position-on-electricity-market-reform/. France wants CfDs to cover existing assets, namely its nuclear fleet, while Germany views this as unfair support that would distort markets. In late July and ahead of summer recess, the European Parliament voted on a watered-down version of the Commission’s proposal, making only newly-built plants eligible for CfD funding.73Nikolas Kurmayer, “European Parliament votes for minimal electricity market reform”, Euractiv, July 20, 2023, https://www.euractiv.com/section/electricity/news/european-parliament-votes-for-minimal-electricity-market-reform. Negotiations between the European Council, the European Parliament and the European Commission will accelerate towards the end of the year, under the supervision of the Spanish Council presidency.

Sven Giegold, German state secretary for economy and climate, recently told the Financial Times that France and Germany needed a “grand bargain” on energy.74Alice Hancock, “Germany seeks ‘grand bargain’ with France over energy”, Financial Times, 4 October 2023 https://www.ft.com/content/8a57f1be-20cb-4632-aecd-1a68f5211057 Indeed, the need for a political grand bargain on nuclear energy in the EU is clear: to resolve divisive disputes and reestablish trust in the consensus-building process, to streamline broader energy policy that depends on nuclear strategy, and to meet the objective of supporting low-carbon technology essential to the European economy. Given the centrality of energy it remains—as it was in 1958 with the launch of Euroatom—a geopolitical necessity. Otherwise, a deep source of disunion will continue to drive European member states apart. Above all else, ambitious targets for EU-wide decarbonization are simply unrealistic without nuclear energy—but its use must be defined by a new strategy that would guarantee Europe’s energy security and resilience against energy-based extortion from foreign producers.

What does a peace pact on nuclear energy look like?

It is time to resolve divisive disputes on nuclear energy and find a compromise that defines the role of the power source in the energy transition. This will require a political—not a technocratic or a technical —decision. As a quarter of all electricity supply and about half of the low-carbon generation in the EU, nuclear energy is essential, strategic, and will complement the deployment of renewables and ensure energy security and independence.75“Nuclear Power in the European Union,” World Nuclear Association. Member states, principally Germany, should respect individual decisions to develop their energy mix as they see fit, as long as emission reductions are reached. Member states, principally France, also need to drop their hostility to the deeper integration of European electricity markets. Together they should look to a long-term solution on electricity pricing that can square the various circles holding Europe back. The EU should do this in ways which can help the strategically important sector overcome the politics of both German-led supranational opposition and French-led domestic underperformance.

First, European member states, in particular France and Germany, should sign a peace pact on nuclear energy. This should take the form of a political neutrality agreement on the topic of nuclear energy that affirms that each state is free to choose its own energy mix, as is defined by the treaties, stops interference in these policies, and affirms there is no right to block member states wishing to launch, expand, or simply conserve their nuclear capacity. Both sides should acknowledge that nuclear and renewable energy will both play a vital role in reaching emission reduction targets. As a continent facing a rapid rise in temperatures, Europe has no time to lose to decarbonize its energy mix. But as a compromise this pact would recognize that nuclear energy generation is a complement, not a substitute, to renewable energy targets. Therefore, nuclear generating countries should commit—in exchange for the peace pact—to deeper integration of European electricity markets, new targets for the deployment of renewables, while supporting reforms to simplify and accelerate permitting, and investing in additional cross-border grid connections, with the support of EU money, via existing funding instruments and the European Investment Bank, whilst looking for a long term solution on electricity pricing. In practice, this means that France must abandon plans to subsidize all of its nuclear electricity production, including its requirement that CfDs cover existing assets. Not only would this contribute to a subsidies race on both sides of the Rhine, it would fundamentally undermine the workings of an integrated European electricity market, notably by making it impossible for France to agree to build the interconnectors Europe needs. Indeed, France would then be subsidizing electricity prices for all of its neighbors.

Second, the Green Deal Industrial Plan (GDIP) and the Net Zero Industrial Act must be revamped. The European Commission should adopt a technology-neutral approach, focusing on emission reduction targets rather than defining a list of strategic sectors. This approach would include placing renewable energy and nuclear energy on the same footing. This method, recently pushed by the Bruegel think tank, is more in line with the treaties enshrining the right of member states to design their energy mix.76Simone Tagliapietra, Reinhilde Veugelers, and Jeromin Zettelmeyer, Policy Brief: Rebooting the European Union’s Net Zero Industry Act, Bruegel, June 22, 2023, https://www.bruegel.org/policy-brief/rebooting-european-unions-net-zero-industry-act. This means that the nuclear industry should not be discriminated against, whether in access to European funding for research & development, nuclear waste treatment, or for nuclear-derived hydrogen.

Third, the benefits of nuclear energy are only fully reaped when strong supply chains exist, supported by skilled workers. The European Commission should ramp up efforts to support nuclear skill development, as well as research and development efforts. Europe, as recent problems in the French nuclear sector show, lacks crucial skills. Pursuing nuclear energy independence only works if a strong domestic industry can support and share markets for labor and materials that are not overly reliant on Russia. A critical policy objective should be to improve access to training and enhancing existing skills for operating nuclear energy equipment. Investing in skilled labor and materials across the nuclear supply chains will reduce capital and operating costs, address construction delays, and reestablish efficiency across the value chain. Fostering technological innovation should be another goal of EU energy policy. The majority of large European nuclear power plants are regarded as nearing the end of their operational lives, need better fuel efficiency, and face issues with water shortages. Member states will need to identify opportunities to address these deficiencies as part of their overall decarbonization strategies. Currently, there is an acute lack of resources across the board, as France’s problems illustrate.

Fourth, the concerns of the anti-nuclear camp must be addressed with a focus on nuclear waste. While the benefits are clear, critiques against nuclear energy use—as voiced by Germany and its anti-nuclear allies—must be addressed. Even though safety precautions with nuclear power plants have dramatically increased since the Chernobyl disaster, the more-recent Fukushima incident convinced many—including the Green Party, which holds the crucial economic affairs and climate action portfolios in Germany’s cabinet—that the risks of nuclear power are too high. This must be addressed with a new focus on research into waste, safety, and nuclear management in any grand bargain.

Finally, in the same way that Europe has made drastic (and successful) efforts to reduce Russian gas dependencies, the European Union should be reducing the Russian presence in European nuclear markets, notably for Russian uranium.77Victor Jack, “French-Russian Nuclear Relations Turn Radioactive,” Politico, April 20, 2023, https://www.politico.eu/article/french-russian-nuclear-relations-radioactive-rosatom-sanctions/. This will require the continued authorization of new fuel sources to replace Russia’s supply, which has already begun. One recent case: Orano Mining, which is partially owned by the French state, concluded a memorandum of understanding with Kazakhstan to help the EU recognize the potential of the world’s largest uranium exporter.78“Orano Has Signed a Memorandum of Cooperation in the Uranium Industry with Kazatomprom,” Orano, December 5, 2022, https://www.orano.group/en/news/news-group/2022/december/orano-has-signed-a-memorandum-of-cooperation-in-the-uranium-industry-with-kazatomprom. On this point, France will need to pay heed to other member states’ concerns on the outsized influence that Rosatom has, especially in terms of enrichment capacities. This is an area where deepened cooperation between Europe and its Western allies can bring significant benefits. Indeed, spare capacity exists, notably in France, Canada, and the United States, across the different steps of the nuclear fuel value chain: from mining to conversion, enrichment, and fuel fabrication.79Matt Bowen and Paul M. Dabbar, Reducing Russian Involvement in Western Nuclear Power Markets, Center on Global Energy Center, Columbia University, https://www.energypolicy.columbia.edu/publications/reducing-russian-involvement-western-nuclear-power-markets/.

Conclusion

The February 2022 invasion of Ukraine exposed the fragility of Europe’s dependence on Russian hydrocarbons for its energy needs. EU policymakers have acted impressively to mitigate the effects of short-term energy shocks, but measures for long-term resilience are losing momentum and are threatened by unresolved conflict around the role of nuclear energy in the energy transition, as demonstrated by the failure to even mention nuclear energy in the RePowerEU response plan. Failing to reach a European consensus on nuclear energy will further degrade political capital and trust, and additionally jeopardize ambitious targets for decarbonization that already seem out of sight. Nuclear energy, with its low-carbon and reliable electricity generation, can play a significant role in ensuring energy security and meeting decarbonization targets. However, it is currently stymied by both the politics of German-led supranational obstruction and French-led domestic underperformance. A “peace pact” on nuclear energy in Europe and a package to allow the nuclear energy sector to compete has the potential to accelerate broader energy transition policies, restore trust in consensus building, and reestablish the EU as a climate leader. This will be a political—not a technocratic or a technical—decision and requires European leaders to recapture the spirit of technological optimism and geopolitical purpose that first birthed Euroatom. In short, the spirit of the Atomium.

Policy recommendations

- To resolve deep divisions, EU members should sign a peace pact on nuclear energy. This should take the form of a political neutrality agreement on the topic of nuclear energy that affirms that each state is free to choose its own energy mix, stops interference in these policies, and also affirms there is no right to block member states wishing to launch, expand, or simply conserve their nuclear capacity.

- To do so, subsidy schemes targeted at existing nuclear assets should be dropped, as they undermine the functioning of European electricity markets and its further integration via interconnectors.

- To make this viable,EU members should agree to place renewable and nuclear sources of power on the same footing under the GDIP and NZIA. This would implement a technology-neutral approach to lowering carbon emissions.

- In exchange, nuclear generating EU members should commit to deeper integration of European electricity markets, new targets for the deployment of renewables, while supporting reforms to simplify and accelerate permitting, and investing in additional cross-border grid connections, with the support of EU money, via existing funding instruments and the European Investment Bank, whilst looking for a long term solution on electricity pricing.

- To strengthen such an effort, the European Commission should support nuclear engineering skills development, along with research and development capabilities.

- To address concerns, EU members should redouble efforts to research, address, and manage nuclear waste disposal.

- Finally, EU members with Western allies should reduce their reliance on Russian sources of uranium. While fully decoupling from Russian uranium imports will likely be infeasible in the short to medium term, the EU should diversify its sources of uranium to avoid having the Kremlin keep its existing advantageous position in the EU uranium supply.

Related content

About the authors

Ben Judah is director of the Transform Europe Initiative and a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Europe Center. He is the author most recently of This Is Europe and his research interests focus on the geopolitics of decarbonization, Britain and the European Union.

Rachel Rizzo is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Europe Center. Her research focuses on European security and the transatlantic relationship.

Théophile Pouget-Abadie is a nonresident fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Transform Europe Initiative and policy fellow at the Jain Family Institute.

Jonah Allen is a nonresident fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Europe Center and a research fellow at the Jain Family Institute.

Francis Shin is a research assistant at the Atlantic Council’s Europe Center.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Jennifer Gordon, Dr. Matthew Bowen, Shahin Vallée and Cécile Maisonneuve for their invaluable insights and feedback in the writing of this report.

Image: A general view shows cooling towers and reactors of the Electricite de France (EDF) nuclear power plant in Cattenom, France, June 13, 2023. REUTERS/Yves Herman