Tunisia needs both bread and freedom

Bottom lines up front

- Strengthening democratic institutions, ensuring transparent governance and independent courts, and expanding political freedoms will create a sustainable and inclusive environment for all citizens.

- New economic reforms are needed to break monopolistic market power, foster genuine competition, and remove bureaucratic barriers to attract both domestic and foreign investment.

- The Tunisian government must become more responsive and accountable to citizens’ growing social and economic grievances in order to prevent further unrest and build the social trust necessary for long-term stability.

This is the sixth chapter in the Freedom and Prosperity Center’s 2026 Atlas, which analyzes the state of freedom and prosperity in ten countries. Drawing on our thirty-year dataset covering political, economic, and legal developments, this year’s Atlas is the evidence-based guide to better policy in 2026.

Evolution of freedom

Tunisia’s trajectory over the past several decades is often described as a story of rupture: an authoritarian stability that gave way to a singular democratic opening in 2011, followed a decade later by a dramatic reversal. The Freedom and Prosperity Indexes data help to clarify that narrative. They show that the post-2011 leap was overwhelmingly political and that legal and economic change was slower and more contested. This imbalance is central to understanding both the initial promise of Tunisia’s democratic transition and the depth of popular disillusionment that later emerged. The post-2021 turn was driven above all by the weakening of institutional constraints and judicial independence.

The presidency of Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, who ruled the country from 1987 to 2011, rested on institutional formalities and tight control. Tunisia held elections, maintained a parliament, and projected administrative capacity, but these mechanisms did not translate into meaningful competition or accountability. Political opposition was fragmented, repressed, or forced into exile, and civil society organizations operated under constant surveillance. This is reflected in the political subindex’s very low baseline prior to 2011. The country displayed an outer shell of formal politics while keeping the substance of political contestation closed, consistent with an electoral autocracy where procedural elements of democracy coexist with pervasive repression.

The pre-uprising period also explains why the 2011 revolution was propelled by the quest for dignity and fairness as much as for formal rights. Social grievances accumulated around the belief that opportunities were unequally distributed. Corruption was distorting markets and access. Regional disparities—between the more prosperous coast and the marginalized interior—had become entrenched. The tension occasionally erupted into localized protests, most notably the 2008 Gafsa mining basin uprising, which was violently suppressed and received little domestic media coverage at the time. Such episodes revealed social and economic cleavages that the authoritarian system was unable and unwilling to address, even as it succeeded in preventing large-scale political mobilization for many years.

The 2011 revolution marked a dramatic rupture in Tunisia’s political trajectory. The collapse of the Ben Ali regime triggered an unprecedented expansion of political freedom, clearly visible in the sharp rise of the political subindex after 2011. Elections became genuinely competitive, political parties proliferated, and civil and political rights were significantly expanded. The adoption of the 2014 constitution represented a high point, enshrining extensive civil liberties, protections for political pluralism, and formal checks on executive power. In comparative terms, Tunisia emerged as the most successful democratic transition to result from the Arab Spring, a status widely acknowledged by scholars and international observers over the decade that followed.

This political opening occurred despite an exceptionally challenging environment. Tunisia faced severe security threats, including terrorist attacks and instability along its border with Libya, which disrupted tourism and deterred investment. Economic performance remained weak, and unemployment persisted at high levels. Nevertheless, political elites repeatedly demonstrated a willingness to compromise in order to preserve the democratic process. In 2013, a deadlock in the “Troika” governing coalition brought the government to a dangerous edge, amid disagreements over the constitutional order and the role of Ennahda, an Islamist party, in the new system. The resolution was not a winner-take-all victory but a negotiated exit: the replacement of the governing coalition by a technocratic government, a path toward general elections, and the adoption of a new constitution in 2014 that was widely seen as liberal. This episode, in which a coalition of civil society organizations stepped in to mediate when politicians were deadlocked, reinforced the perception that Tunisia’s political class was committed to democratic consolidation, even at significant short-term political cost.

Yet the very mechanisms that stabilized the political system during this period also contributed to its longer-term fragility. After the 2014 elections, Tunisia entered a prolonged phase of grand coalition governance, most notably through the Carthage Agreement, which brought together former rivals in the name of stability and consensus. While this arrangement reduced polarization and prevented institutional paralysis, it blurred the distinction between government and opposition and weakened electoral accountability. For many citizens, political competition appeared increasingly disconnected from policy outcomes, reinforcing perceptions of elite collusion and political closure. A system designed to prevent authoritarian concentration can, if it becomes synonymous with permanent compromise among elites, generate a different kind of legitimacy problem.

Additionally, while political freedoms remained high throughout most of the post–2011 decade, improvements were not matched by parallel gains in the economic subindex or legal subindex. Rapid expansion of political freedom was not accompanied by substantive reforms capable of addressing structural economic problems or strengthening the rule of law. As a result, the lived experience of democracy for many Tunisians remained largely unchanged. Daily interactions with the state continued to be shaped by bureaucratic inefficiency, informality, and limited economic opportunity, which combined to erode confidence in the democratic system itself.

Security shocks deepened the sense of vulnerability. Tourism—an essential sector—was severely damaged by major terrorist attacks in 2015 at the Bardo Museum attack and at the resort area of Port El Kantaoui. The fallout was not only a temporary loss of revenue. It also affected employment, foreign exchange, and the confidence that sustains private initiative. Security, as reflected in the Freedom Index, was weaker than it had been before 2011. The unresolved struggle over corruption and transitional justice further complicated the path from political opening to effective governance. After 2011, expectations for accountability were high, including for business elites and networks associated with the old regime. Yet a major dispute emerged over whether to exclude and prosecute old networks or to pursue reconciliation to preserve investment and economic stability. A new network of young activists was formed under the name “I will not forgive (مانيش مسامح)” to demand accountability before reconciliation. The Truth and Dignity Commission, established in a 2013 law, became a focal point for these debates, and the broader dilemma—accountability versus “turning the page”—stoked public frustration when citizens saw that the most powerful actors often appeared to escape consequences. Tunisia’s institutional design also had a missing pillar: the constitutional court. Debated and delayed over many years, it was never established in a way that allowed it to play its intended role, leaving the system more exposed when executive power later expanded.

Daily interactions with the state continued to be shaped by bureaucratic inefficiency, informality, and limited economic opportunity, which combined to erode confidence in the democratic system itself.

The growing gap between political openness and material outcomes contributed to widespread political disengagement. Voter turnout declined, trust in political parties fell, and frustration with parliamentary politics intensified. The 2019 elections revealed the depth of this disillusionment, producing a highly fragmented legislature and propelling Kais Saied, an independent candidate with no party affiliation, to the presidency. Saied’s campaign capitalized on popular resentment toward political elites, framing the post-2011 democracy as a system captured by self-serving parties and informal networks rather than a vehicle for genuine popular representation. On July 25, 2021—celebrated in Tunisia as Republic Day, marking the 1957 abolition of the monarchy—President Kais Saied dismantled key features of the post-2011 balance of power. Parliament was suspended and then dissolved, executive authority was re-centralized, and Tunisia moved toward a new constitutional framework.

Although elections continued to be held, their substance changed fundamentally. New electoral rules marginalized political parties, restricted meaningful competition, and transformed elections into largely individual, nonpartisan contests. Such a design undermines parties as channels of representation and reduces collective accountability, even if the formal mechanics of voting persist. It also reshapes how citizens can aggregate interests and how opposition can organize—core elements of pluralism that matter beyond the existence of polling stations.

The crackdown on the judiciary is central to the post-2021 reversal. After 2011, judicial independence increased dramatically according to legal subindex data—only to plummet again in 2021. One of the main institutional gains of Tunisia’s transition post-2011, the judiciary became one of the first targets of executive pressure. Judges and lawyers who opposed executive moves faced dismissal, prosecution, or detention, and the space for independent legal contestation narrowed. In a context where a constitutional court never materialized, this degree of pressure on the judiciary further reduced the system’s ability to provide institutional checks.

By 2024, Tunisia’s freedom landscape has dramatically deteriorated. While the civil liberties subindex shows a relatively steady trend through 2024, the aggregate data obscures the rapid changes that have eroded those liberties since the 2021 coup. For instance, recent evidence documents a sharp increase in arbitrary detentions, prison torture, and suspicious deaths in custody. Similarly, core institutional safeguards of democratic governance—constraints on executive power, a credible separation of powers, and an independent judiciary—have deteriorated markedly as shown by the other freedom subindexes. The Freedom Index data (with its subindexes) highlights the limits of political liberalization when it is not embedded in broader reforms of the state and the economy. Democratic transitions, like Tunisia’s, are revealed to be fragile in contexts where political institutions are not accompanied by social and economic reforms to sustain them.

From freedom to prosperity

The evolution of prosperity in Tunisia since 1995 provides a sobering counterpoint to the dramatic political changes captured by the Freedom Index. Unlike political freedom, which experienced sharp discontinuities after 2011 and again after 2021, the Prosperity Index reveals a far more muted and gradual trajectory. Income, education, health, inequality, and other components show limited responsiveness to political transformation, highlighting the structural constraints that have long shaped Tunisia’s development. The central lesson is not that the country made no social progress after 2011, but that prosperity did not accelerate in a way that matched the expectations unleashed by the political opening.

The central lesson is not that the country made no social progress after 2011, but that prosperity did not accelerate in a way that matched the expectations unleashed by the political opening.

Income captures this dynamic directly. Economic performance under the Ben Ali regime was often portrayed as relatively strong by regional standards, yet this growth was unevenly distributed and heavily reliant on low-value-added sectors such as tourism and assembly-based manufacturing. Real income growth was modest, and job creation lagged behind demographic pressures. Inequality and regional disparities remained entrenched, particularly between coastal areas and the country’s interior.

In public debate, the revolution carried an implicit promise that political voice would translate into economic opportunity, especially for young people and marginalized regions. Nonetheless, the post-2011 period did not produce a decisive break with the previous pattern. Democratic transitions are often associated with short-term economic disruptions, but Tunisia’s stagnation persisted well beyond the initial adjustment period. Not only did the economy not show a clear acceleration in income growth or improvements in labor market outcomes, but economic uncertainty actually increased in the wake of the revolution, as security concerns, declining tourism revenues, and fiscal pressures constrained growth. Foreign investment remained subdued, and successive governments struggled to articulate and implement coherent economic reform strategies amid political fragmentation. When expectations are high, incremental prosperity gains can feel like stagnation, and the perception that democracy failed to deliver material benefits to the majority of citizens becomes politically consequential.

Education and health outcomes continued to improve gradually, but these trends largely reflected preexisting trajectories rather than new policy breakthroughs. Tunisia entered the post-2011 period with relatively strong human capital indicators compared to many peers in the region, and incremental progress continued despite fiscal constraints. However, these gains were insufficient to offset rising unemployment, especially among educated youth, which became one of the most visible and politically salient failures of the post-revolutionary order.

Similarly, inequality improved only modestly after 2011. The uprising was fueled in part by grievances about unequal access and regional exclusion, yet the prosperity data suggests that inclusion advanced gradually rather than decisively. Tunisia’s economic structure helps explain this. The country has long displayed a dualism between an internationally connected, often coastal economy and an interior that experiences weaker public services, fewer jobs, and less investment. Persistently high informality reinforces this dualism by limiting productivity growth and reducing the reach of social protection.

Tunisia has maintained a respectable environmental profile according to the Prosperity Index data, as the country avoided the extreme environmental degradation observed in some rapidly industrializing countries. For many citizens, the post-2011 decade was shaped more by jobs, prices, public services, and security than by environmental policy. Environmental performance matters, yet it does not substitute for the everyday pressures that drive political legitimacy.

The minorities component is where prosperity intersects most directly with the post-2021 political turn. The index shows improvement after 2011, consistent with a wider opening of civic space. But this progress reverses after 2021. The reversal aligns with an increasingly hostile discourse targeting sub-Saharan African migrants and Black Tunisians, including rhetoric drawing from a “replacement” narrative.

The path forward

Overall, Tunisia’s freedom and prosperity scores tell the unfinished story of the 2011 revolution—calls for freedom, dignity, and social justice remain partially unanswered. The path forward requires Tunisia to balance economic reforms with political liberalization. Freedom alone will not achieve prosperity, and prosperity alone will not guarantee freedom. While recent years have registered gradual increases in prosperity metrics, these numbers hide deep structural economic challenges: limited market integration, lack of investment, low buying power, and stagnation in technology and innovation.

Freedom alone will not achieve prosperity, and prosperity alone will not guarantee freedom.

Tunisia needs comprehensive economic reform that fundamentally addresses market structure. Breaking up concentrated market power and fostering genuine competition in key sectors must be prioritized. Competition drives innovation, efficiency, and ultimately the job creation that Tunisians desperately need. Without competitive markets, growth will remain anemic and unable to generate sustainable long-term development. New trade agreements, beyond monopolistic arrangements, will boost market access and competitiveness. Tunisia enjoys close proximity to European and African markets, and it is not fully exploiting this potential. The country must engage with new partners and expand its trade structure.

Investment also needs to reach its potential. As a Mediterranean hub with attractive potential across energy, tourism, and technology, Tunisia should nurture its private sector by encouraging domestic and foreign investment. The current legal framework and bureaucratic barriers deter new investors. The country should diversify its investment pool and position itself as a North African hub connecting Africa, Europe, and Asia.

Energy remains underrepresented despite its vast potential. Tunisia possesses exceptional solar energy capacity due to long days and abundant sunlight, yet it depends heavily on imported oil and gas while energy needs increase annually. Solar energy constitutes only a small fraction of total electricity production. In December 2025, a new solar panel project was initiated in the city of Kairouan to address this gap. More renewable energy projects are needed to reduce oil and gas dependency, satisfy citizen needs, and avoid the electricity outages that have become increasingly common during summer months. Wind energy could also be further developed to produce clean, sustainable power.

Another major barrier is low buying power among citizens, driven by high inflation, stagnant growth, high public debt, import dependency, and shortages of basic goods. In recent years, the country has faced significant medical supply crises, and several products are no longer available due to low foreign currency reserves and budget constraints. People with chronic conditions now lack basic medication or must wait for alternatives. Food prices remain high relative to incomes, and the country has experienced shortages in flour, sugar, coffee, and milk. If prices remain high and inflation persists, social unrest will intensify.

Tunisia once stood at the forefront of technological advancement but has fallen behind in digitalization, electronic transactions, and artificial intelligence. The country is not only failing to invest in new technologies but also losing its best engineers and researchers, who migrate elsewhere in search of better economic opportunities and political stability.

Yet economic reforms alone will prove insufficient without parallel political liberalization. Tunisia’s economy cannot reach its potential in an environment where property rights remain uncertain, contracts are unreliably enforced, and regulatory decisions lack transparency. Investors, both domestic and foreign, need confidence that there are legal protections for their investments, that courts function independently, and that political connections do not determine business success.

Strong state institutions that operate transparently and responsibly are prerequisites for sustained economic development. Absent these, reforms are merely cosmetic exercises that benefit connected elites instead of delivering broad-based growth. Economic rights, such as to own property, enforce contracts, and operate businesses without arbitrary interference, require robust legal frameworks and independent judiciaries to defend them.

Political freedom and economic development are not competing priorities but complementary necessities. When citizens can express grievances, participate in decision-making, and hold leaders accountable, economic policies better reflect genuine needs rather than narrow interests. Political openness creates pressure for responsive governance, reduces corruption, and builds the social trust necessary for economic cooperation.

Tunisia’s future depends on finding the right balance between pursuing market reforms and global integration while strengthening democratic institutions and protecting fundamental freedoms.

The accumulation of unaddressed economic grievances breeds frustration that political repression cannot permanently contain. Tunisia needs a social contract where economic opportunities expand alongside political voice, where growth translates to improved living standards for ordinary citizens, not just elites. This means not only GDP growth but attention to employment quality, income distribution, and access to services. The country has witnessed increasing protests in 2025, with more occurring in early 2026, including a nationwide strike organized by UGTT, the country’s influential organized labor confederation. Tunisia’s future depends on finding the right balance between pursuing market reforms and global integration while strengthening democratic institutions and protecting fundamental freedoms. Only this combination can deliver sustainable prosperity that satisfies citizen aspirations and builds a stable foundation for long-term development.

about the author

Ameni Mehrez is an assistant professor of government at the College of William & Mary and a nonresident fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School’s Middle East Initiative program. She holds a PhD in political science from Central European University. Her main areas of expertise are public opinion surveys, political attitudes, electoral behavior, and party politics in the Arab-Muslim world. Currently, she serves as the co-principal investigator of the Arab Elections project.

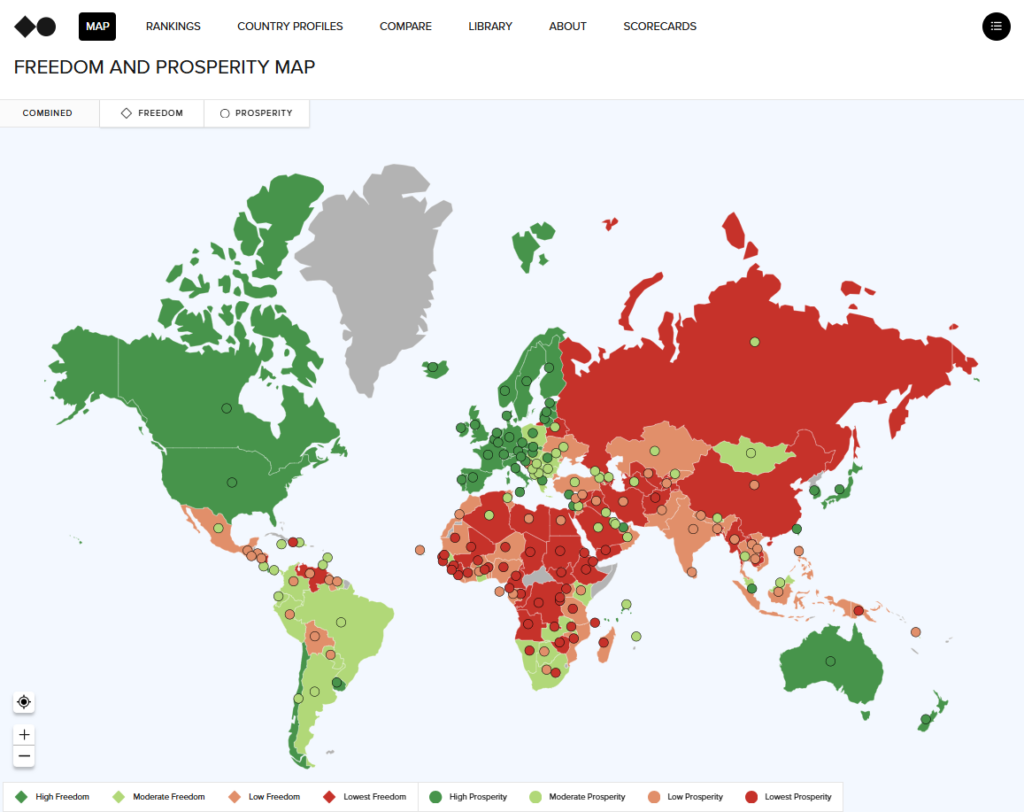

Explore the data

The Indexes rank 164 countries around the world. Use our site to explore thirty years of data, compare countries and regions, and examine the subindexes and indicators that comprise our Indexes.

Stay Updated

Get the Freedom and Prosperity Center’s latest reports, research, and events.

Stay connected

Read all editions

2026 Atlas: Freedom and Prosperity Around the World

Against a global backdrop of uncertainty, fragmentation, and shifting priorities, we invited leading economists and scholars to dive deep into the state of freedom and prosperity in ten countries around the world. Drawing on our thirty-year dataset covering political, economic, and legal developments, this year’s Atlas is the evidence-based guide to better policy in 2026.

2025 Atlas: Freedom and Prosperity Around the World

Twenty leading economists, scholars, and diplomats analyze the state of freedom and prosperity in eighteen countries around the world, looking back not only on a consequential year but across twenty-nine years of data on markets, rights, and the rule of law.

2024 Atlas: Freedom and Prosperity Around the World

Twenty leading economists and government officials from eighteen countries contributed to this comprehensive volume, which serves as a roadmap for navigating the complexities of contemporary governance.

Explore the program

The Freedom and Prosperity Center aims to increase the prosperity of the poor and marginalized in developing countries and to explore the nature of the relationship between freedom and prosperity in both developing and developed nations.

Image: People wave national flags during celebrations marking the fifth anniversary of Tunisia's 2011 revolution, in Habib Bourguiba Avenue in Tunis, Tunisia January 14, 2016. REUTERS/Zoubeir Souissi

Keep up with the Freedom and Prosperity Center’s work on social media